Le Cambodge, II Les provinces siamoises | The Siamese Provinces

by Etienne Aymonier

The Khmer cultural and artistic heritage in the Siamese sphere of influence at the turn of the 20th century.

Type: e-book

Publisher: Leroux, Paris | Vol II of 'Le Cambodge' par Etienne Aymonier, Directeur de l'Ecole Coloniale.

Edition: via bnf.gallica

Published: 1910

Author: Etienne Aymonier

Pages: 480

Language : French

Indefatigable explorer, multi-talented researcher, Etienne Aymonier had solid connections with the highest levels of the Kingdom of Siam, including a close friendship to Prince Damrong.

In this detailed books, he asserts himself as a pioneer in the archaeological, architectural and historical fields, for instance with:

- the first identification of Ayuthia as “la ville des frontieres royales de l’ancien Cambodge” [“The Royal Border City”], “its Siamese name being the shortening of the Cambodian “Angkor reach sema”, the latter itself a corruption of the Sanskrit Nagarajasema”, “nowadays Old Korat and not the district capital founded by the Siamese.”

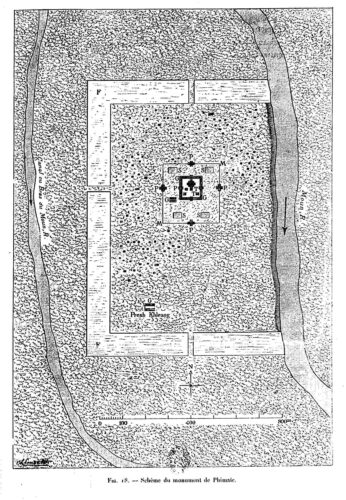

- the first detailed description of the Sukhotai and Phimai sites, with this map of “Phimaie” for instance:

- the first attempt in deciphering and interpreting the Sdok Kak Thom (“The Lake of the Big Reeds”) stele found in the Sisophon region, a major epigraphic discovery.

Read the ebook

This book has been translated into English: Khmer heritage in the old Siamese provinces of Cambodia : with special emphasis on temples, inscriptions, and etymology (trans. by Walter E. J. Tips, Lotus Press, Bangkok, 1999, 302 p)

Tags: Siam, Khmer Empire, archaeology, Khmer arts, Sisophon, Bassac, Battambang, epigraphy

About the Author

Etienne Aymonier

Étienne François Aymonier (26 Feb 1844, Le Chatelard, France – 21 Jan 1929, Paris), French linguist and explorer, was the first French scientist to extensively survey the ruins and inscriptions of the Khmer empire in today’s Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and southern Vietnam. Le Cambodge (three volumes published) from 1900 to 1904, remains to these days an important source for geographers, historians and epigraphists.

First director of the École Coloniale, he assembled a large collection of Khmer sculpture later housed in the Guimet Museum, Paris. He is also the author of a dictionary of the Cham language.