Un pèlerin d'Angkor

by Pierre Loti

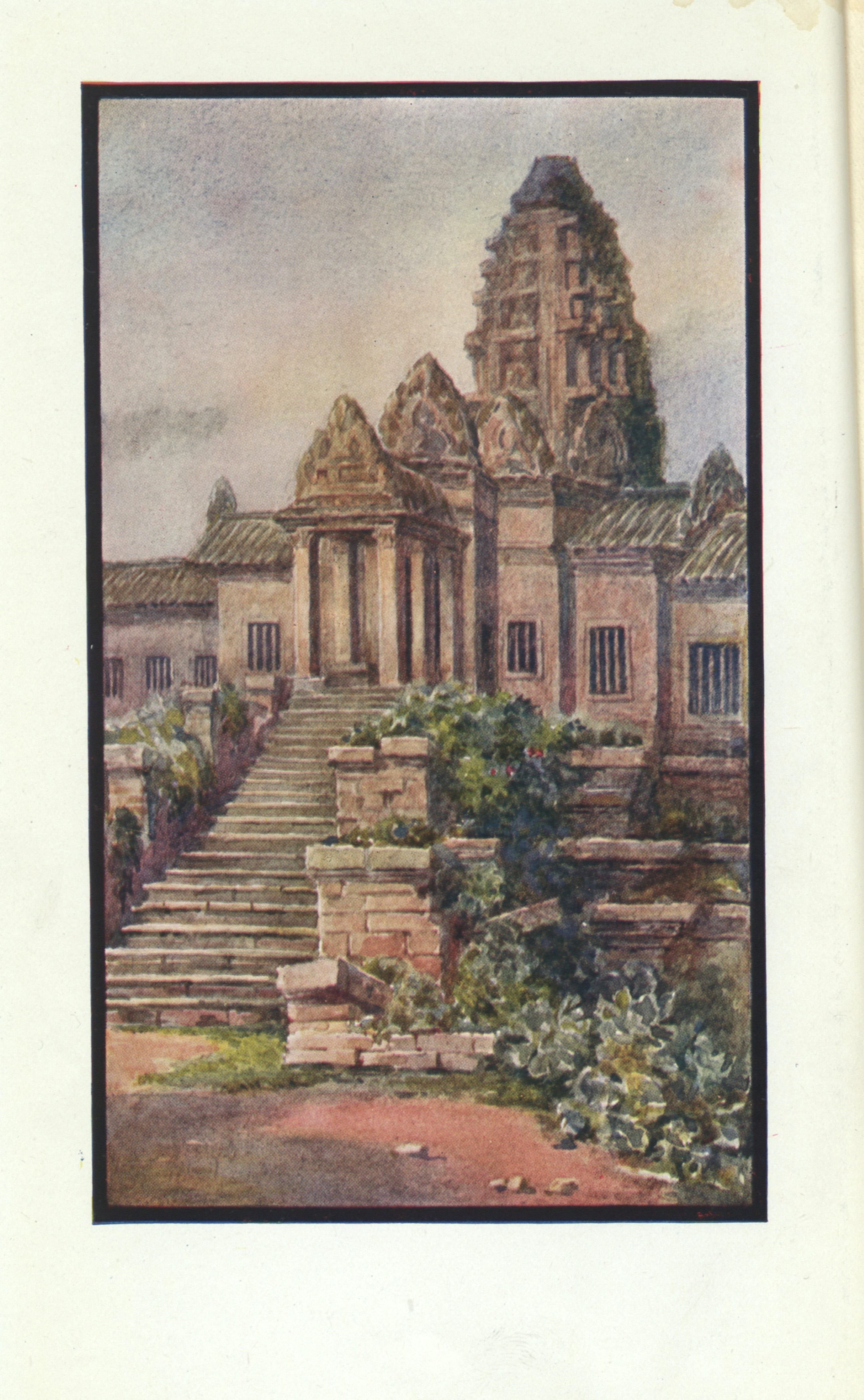

One of the most inspired (and inspirational) travelogues on Angkor in the pioneering times.

- Formats

- e-book, ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- Calmann-Lévy, Paris.

- Edition

- 1) print: Editions Kailash "Les Exotiques", reedition | 2) ebook: Internet Archive, Oct. 2017.

- Published

- 1912

- Author

- Pierre Loti

- Pages

- 248

- Language

- French

pdf 5.9 MB

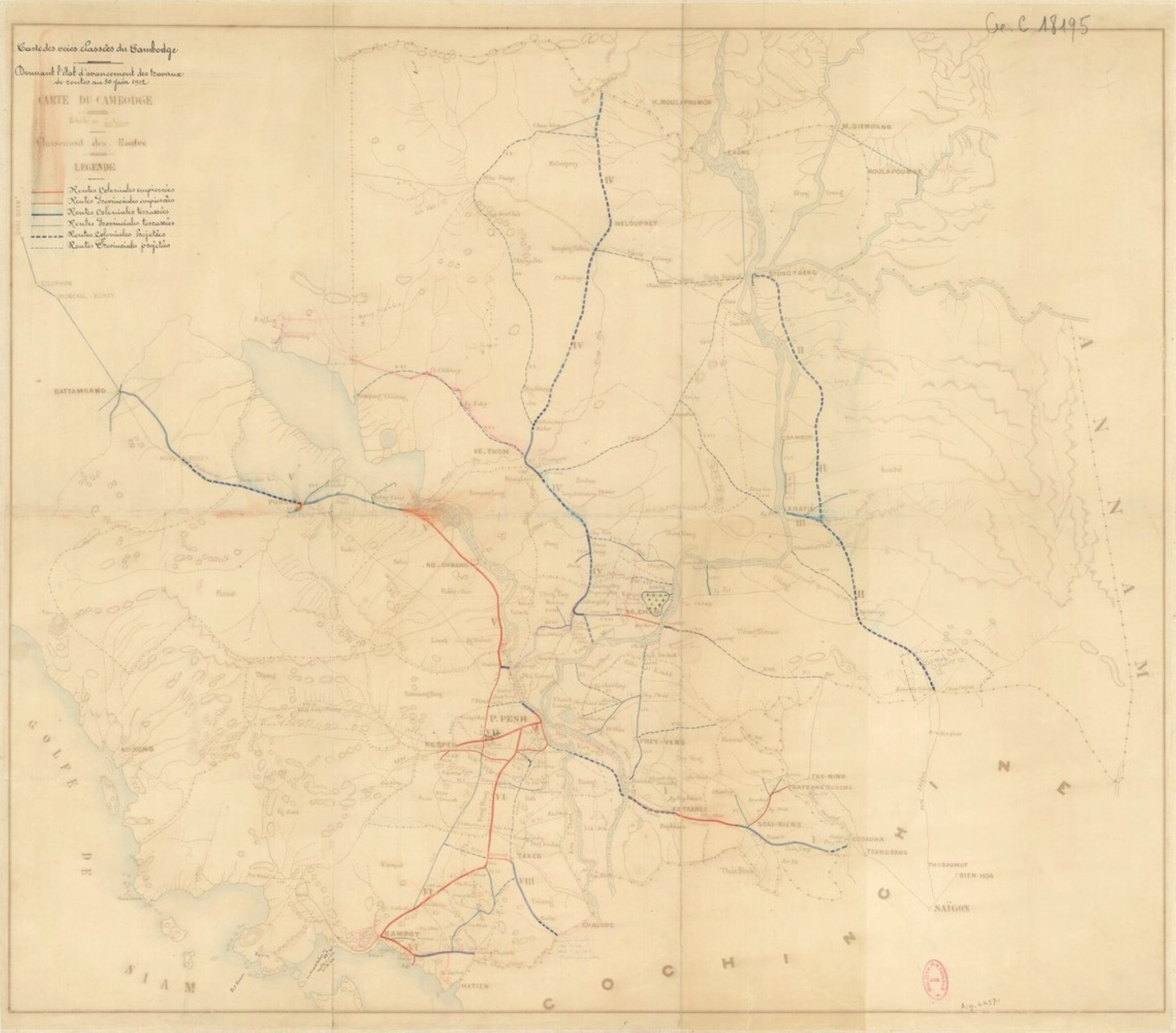

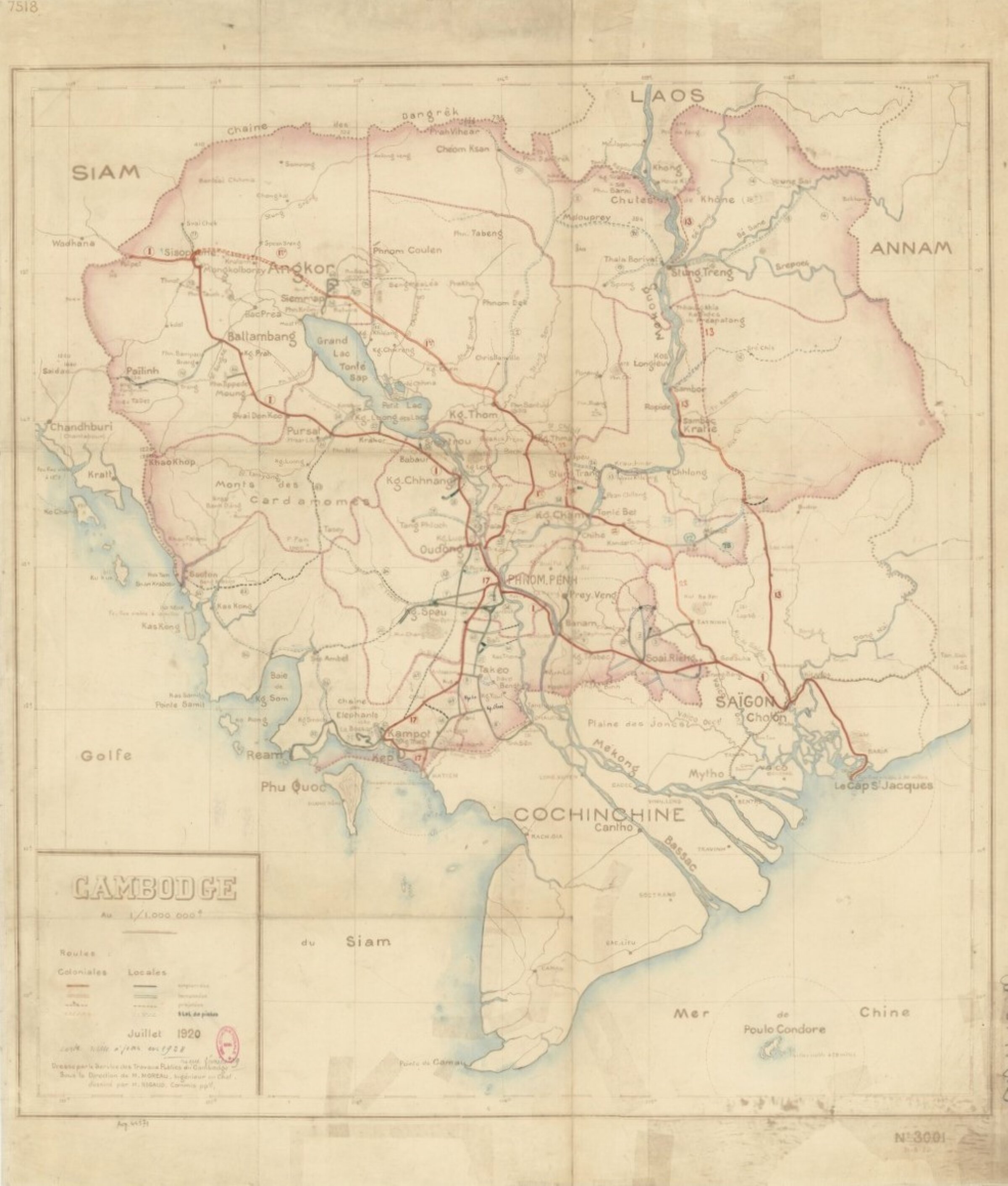

En 1901, French writer Pierre Loti, a master in orientalist and ¨exotic erotic¨ literature, reaches the Angkor complex, rediscovered by Western explorers only two decades before. The sight conjures powerful images, romantic evocations and musings about “intuitive religions”.

During another trip, in November 1904, he revisited Angkor and, back to Phnom Penh by boat and elephant, was invited to the Royal Palace by King Norodom I, giving the following depiction of the evening [obviously set at Chanchaya Pavilion]:

“Dans des girandoles et sur des torchères cambodgiennes en argent – où naguère encore né brûlaient que des mèches imbibées d’huile – la lumière électrique vient d’être récemment installée ; un peu déconcertante ici, elle éclabousse avec brutalité la foule des princesses, des suivantes, des serviteurs, des musiciens, les cinq ou six cents personnes accroupies à terre sur des nattes : rien que des costumes blancs, des draperies blanches, et beaucoup de bras nus, de seins nus d’une couleur de bronze clair. L’orchestre, dès que nous paraissons, commence une musique d’Asie qui tout de suite nous emporte dans les lointains de l’espace et du temps. Elle est douce et puissante, donnée par une trentaine d’instruments en métal ou en bois sonore que l’on frappé avec des bâtons veloutés. Il y a des tympanons, des claquebois au clavier très étendu, et des carillons de petits gongs qui vibrent à la façon des pianos joués avec la pédale forte. La mélodie est triste infiniment, mais le rythme s’accélère en fièvre comme celui des tarentelles. Sur une estrade, on nous fait asseoir près du lit de repos aux matelas dorés où le vieux roi infirme et presque moribond va venir s’étendre. Près de nous, sur une table également dorée, on a posé des coupes à champagne, et des boîtes en or rouge du Cambodge remplies de cigarettes. Nous dominons la salle, dont le milieu, tapissé de nattes blanches et assez vaste pour y faire manoeuvrer un bataillon, reste vide: c’est là que le spectacle du ballet nous sera offert. (…) Il tardait à paraître, le roi, et maintenant des serviteurs apportent et déposent sur un coussin près de nous sa couronne et son sceptre d’or, garnis de gros rubis et de grosses émeraudes. Il est décidément trop malade, il nous prie de l’excuser et nous envoie les attributs souverains, pour bien nous marquer que la réception quand même est royale. Le spectacle va donc commencer sans lui. La musique, tout à coup, se fait plus sourde et plus mystérieuse, comme pour annoncer quelque chose de surnaturel. L’une des portes du fond s’ouvre ; une petite créature adorable et quasi chimérique se précipite au milieu de la salle : une Apsâra du temple d’Angkor ! Impossible d’en donner l’illusion plus parfaite ; elle a les mêmes traits parce qu’elle est de la même race pure, elle a le même sourire d’énigme, les paupières baissées et presque closes, la même gorge de toute jeune vierge, à peine voilée sous un mince réseau de soie. Et son costume est scrupuleusement copié sur les vieux bas-reliefs, mais copié en joyaux vrais, en étoffes magnifiques ; des espèces de gaines en drap d’or emprisonnent ses jambes et ses reins. Le visage tout blanc de fard et les yeux allongés artificiellement, elle porte une très haute tiare d’or, mouchetée de rubis, dont la pointe s’effile comme celle d’un toit de pagode, et, aux épaules, des espèces d’ailerons, de nageoires de dauphin, en or et pierreries. En or également et en pierreries, sa large ceinture, les anneaux qui ornent ses chevilles et ses bras nus couleur d’ambre un peu rose. Seule d’abord en scène, la petite Apsâra des vieux âges, échappée du bas-relief sacré, fait des signes d’appel vers cette porte du fond – qui devient pour nous la porte des apparitions féeriques – et deux de ses soeurs accourent la rejoindre, deux nouvelles Apsâras, aussi étincelantes, les hanches moulées dans les mêmes gaines rigides, portant les mêmes tiares d’or et les mêmes ailerons d’or. Elles se prennent par la main toutes trois. Ce sont des reines d’Apsâras sans doute, car un trône a été préparé pour les faire asseoir. Mais elles échangent une mimique d’inquiétude, et recommencent des signes d’appel, toujours vers cette même porte… On était déjà émerveillé d’en voir trois. Est-ce que par hasard il en viendrait d’autres ?… Et c’est par groupes qu’elles arrivent, dix, vingt, trente, parées en déesses comme les premières, tout le trésor du Cambodge est sur leurs têtes et sur leurs épaules charmantes.

“Devant les trois reines assises, elles vont exécuter des danses rituelles, qui sont des danses presque sur place et plutôt des frémissements rythmés de tout leur être. Elles ondulent comme des reptiles, ces petites créatures sveltes, adorablement musclées et qui semblent n’avoir pas d’os. Parfois elles étendent les bras en croix, et alors l’ondulation serpentine commence dans les doigts de la main droite, remonte en suivant le poignet, l’avant bras, le coude, l’épaule, traverse la gorge, se continue du côté opposé suit l’autre bras et vient mourir aux extrêmes phalanges de la main gauche, surchargée de bagues. Dans la vie réelle, ces petites ballerines exquises sont des enfants très gardées, souvent même des princesses de sang royal, que l’on n’a le droit ni d’approcher ni de voir. On les assouplit dès le début de la vie à ces mouvements qui né paraissent pas possibles pour des membres humains ; à ces poses si peu naturelles, qui cependant sont de tradition immémoriale dans ce pays, ainsi que l’attestent les personnages de pierre habitants des ruines. Elles vont mimer à présent des scènes du Ramayana, telles que jadis elles furent inscrites dans le grès dur, aux bas-reliefs du temple ancestral. Et voici leurs beaux chars de guerre qui font leur entrée, copiés en petit sur ceux d’Angkor-Vat. Mais, par une convention naïve, les éléphants qui devraient les traîner ont été remplacés par des hommes, marchant à quatre pattes, tout nus et tout jaunes, coiffés de grosses têtes en carton avec trompes et oreilles articulées. Alors nous assistons à des épisodes gracieux ou tragiques, à des combats contre des monstres, surtout à des défilés de cortèges pour célébrer des victoires. On voit une petite reine de quatorze à quinze ans, très constellée, très fardée, idéale sur son char de guerre, poursuivie par les déclarations d’amour d’un jeune guerrier et les repoussant avec une grâce infiniment chaste ; on voit mille choses délicates et charmantes, qui témoignent de l’art le plus affiné. Chaque fois qu’une théorie d’Apsâras se retire par l’une des portes du fond, une autre théorie apparaît à l’autre porte et vient lentement occuper la salle. Il en est quelques-unes, de ces petites fées tout en or, qui peuvent bien avoir sept ou huit ans, et qui défilent, peintes comme des idoles, casquées de trop hautes tiares, avec des ailerons de pierreries aux épaules, dignes et graves en des attitudes hiératiques. (…)

“Puisse la France, protectrice de ce pays, comprendre que le ballet des rois de Pnom-Penh est un legs sacré, une merveille archaïque à né pas détruire!…”

“In girandoles and on Cambodian silver torchieres – where until recently only wicks soaked in oil burned – electric light has recently been installed; a little disconcerting here, it brutally splashes the crowd of princesses, following, servants, musicians, the five or six hundred people squatting on the ground on mats: nothing but white costumes, white draperies, and many bare arms, bare breasts of a light bronze color. As soon as we appear, the orchestra starts some Asian music which immediately takes us into the distance of space and time. It is soft and powerful, given by around thirty instruments in metal or wood. There are tympanonswe striked with velvety sticks, clappers with a very extended keyboard, and chimes of small gongs which vibrate like pianos played with the loud pedal. The melody is infinitely sad, but the rhythm accelerates into fever like that of tarantella. On a platform, we are made to sit near the daybed with the golden mattresses where the old, infirm and almost dying king will come to lie down. Near us, on an equally gilded table, are at our disposal champagne glasses and boxes in Cambodian red gold, filled with cigarettes. We dominate the room, the middle of which, lined with white mats and large enough to maneuver a battalion, remains empty: this is where the ballet spectacle will be offered to us. (…) The king was late in appearing, and now servants bring and place on a cushion near us his crown and his golden scepter, garnished with large rubies and large emeralds. He is definitely too ill, he asks us to excuse him and sends us the sovereign attributes, to show us that the reception is nevertheless royal. The show will therefore begin without him. The music suddenly becomes duller and more mysterious, as if announcing something supernatural. One of the back doors opens; a little, adorable and almost chimerical creature rushes into the middle of the room: an Apsâra from the Angkor temple! Impossible to give a more perfect illusion; she has the same features because she is of the same pure race, she has the same enigmatical smile, the lowered and almost closed eyelids, the same throat of a young virgin, barely veiled under a thin network of silk. And his costume is scrupulously copied on the old bas-reliefs, but copied in real jewels, in magnificent fabrics; a kind of sheath made of cloth of gold imprisons his legs and his kidneys. Her face completely white with makeup and her eyes artificially elongated, she wears a very high golden tiara, speckled with rubies, the tip of which tapers like that of a pagoda roof, and, on her shoulders, a kind of fins, dolphin fins, in gold and precious stones. Also in gold and precious stones, her wide belt, the rings which adorn her ankles and her bare arms, the color of a slightly pink amber. Alone at first on stage, the little Apsâra of old ages, escaped from the sacred bas-relief, makes calling signs towards this door at the back – which becomes for us the door of fairy apparitions – and two of her sisters run there to join her, two new Apsâras, just as sparkling, their hips molded in the same rigid sheaths, wearing the same golden tiaras and the same golden fins. The three of them hold hands. They are undoubtedly queens of Apsaras, because a throne has been prepared to seat them. But they exchange a facial expression of concern, and start calling again, always towards the same door… We were already amazed to see three of them. Would others come by chance?… And it is in groups that they arrive, ten, twenty, thirty, adorned as goddesses like the first one, all the treasure of Cambodia is on their heads and on their charming shoulders.

“In front of the three seated queens, they will perform ritual dances, which are almost done on the same spot, consisting in rather rhythmic quiverings of their entire being. They undulate like reptiles, these little slender, adorably muscular creatures who seem to have no bones. Sometimes they extend their arms in a cross, and then the serpentine undulation begins in the fingers of the right hand, goes up following the wrist, the forearm, the elbow, the shoulder, crosses the throat, continues on the opposite side, follows the other arm and comes to die at the extreme phalanges of the left hand, overloaded with rings. In real life, these exquisite little ballerinas are very guarded children, often even princesses of royal blood, whom l. we have the right neither to approach nor to see. We adapt them from the beginning of life to these movements which do not seem possible for human limbs to these poses which are so unnatural, which nevertheless are of immemorial tradition; in this country, as attested by the stone figures inhabiting the ruins. They will now mimic scenes from the Ramayana, as they were once inscribed in the hard sandstone, in the bas-reliefs of the ancestral temple. And here are their beautiful war tanks making their entrance, copied in small scale from those of Angkor Wat. But, by a naïve convention, the elephants who should be dragging them have been replaced by men, walking on all fours, all naked and all yellow, wearing big cardboard heads with trunks and articulated ears. So we witness graceful or tragic episodes, fights against monsters, especially parades to celebrate victories. We see a little queen of fourteen to fifteen years old, very constellated, very painted, ideal on her war chariot, pursued by the declarations of love of a young warrior and repelling them with infinitely chaste grace; we see a thousand delicate and charming things, which bear witness to the most refined art. Each time a theory of Apsâras withdraws through one of the back doors, another theory appears at the other door and slowly comes to occupy the room. There are some of them, these little fairies all in gold, who may well be seven or eight years old, and who parade, painted like idols, helmeted with too-high tiaras, with jeweled fins on their shoulders, dignified and serious. into hieratic attitudes. (…)

“May France, protector of this country, understand that the ballet of the kings of Phnom Penh is a sacred legacy, an archaic marvel not to be destroyed!”

ADB Input

- Epigraphist and historian George Coedès had read A Pilgrim of Angkor before his first visit to the site in 1912 without being too impressed, yet after he experienced the Khmer ruins directly by himself he was to say to his family: “Je reconnais avec joie que cet homme a ressenti comme personne et rendu, comme lui seul sait le faire, certaines impressions cambodgiennes.” [“I am glad to admit that [Loti] has felt like no one else, and transmitted like only him knows how to, certain Cambodian impressions.”] (cf. Bernard Cros, George Coedès: La vie méconnue d’un découvreur de royaumes oubliés, Bulletin de l’AEFEK n. 22, 2017).

- Quite the political statement: when Loti’s book was published in English one year later, the title was…Siam, plain and simple. [Siam, translated from the French by W. P. Baines, illustrated with photographs and an etching by Edith M. Hinchley, T. Werner Laurie Publishers, London, 1913, and Philadelphia, David McKay, 1914).

Tags: French literature, travelogue, Angkor Wat, Norodom I, dance, music, Royal Ballet of Cambodia, apsara, Apsara dance, royal palaces, Cambodian Royal Ballet

About the Author

Pierre Loti

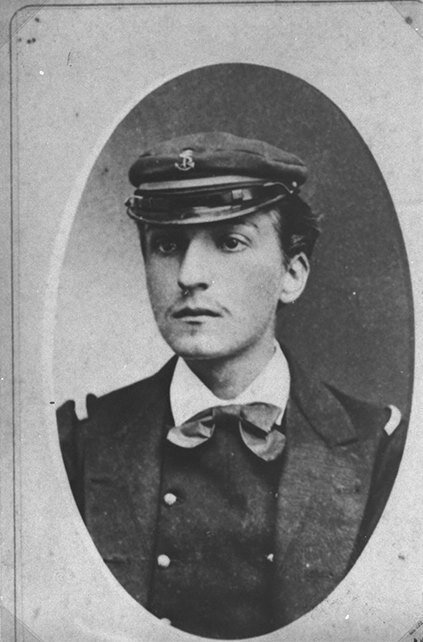

Pierre Loti [born Louis-Marie-Julien Viaud, “Pierre” being a first name suggested by famous actress Sarah Bernhardt and “Loti” the name of an island flower he found in Tahiti] (14 Jan. 1850, Rochefort, France — 10 June, 1923, Hendaye, France) was a French Navy officer, novelist, travel writer, artist, photographer and eccentric art collector who visited Angkor in November 1901, when he was already an established author — he had been elected to Académie Française in 1892 -, publishing Un pélerin d’Angkor [A Pilgrim in Angkor, initially published in English as Siam, 1913] in 1912.

A naval officer serving from 1885 to 1891 on French war ships in China Sea, appointed as ship’s captain in 1906, he became an avid traveler with a fondness for “exoticism”, vising the Middle and Far East, Oceania, North Africa… His first novel, Aziyadé (1879) — which was later interpreted as the hidden account of an homosexual affair -, was an instant success, and his following books settled him as a popular writer: Le Mariage de Loti [originally titled Rarahu] (1880), Le Roman d’un spahi (1881), Pêcheur d’Islande (1886), Madame Chrysanthème (1887), Reflets sur la sombre route (1889), Le livre de la pitié et de la mort (1890), Ramuntcho (1897), Les Désenchantées (1906), Le Roman d’un enfant (1890), Prime Jeunesse (1919), Un jeune officier pauvre (1923)…

The Cahiers Pierre Loti, published in memory of the author from 1952 to 1979 by Association Internationale des Amis de Pierre Loti, claimed that he had always been an “exotic writer, not a colonial writer”, and that he even professed “anti-colonialist” views.His book on Angkor is dedicated to Paul Doumer - former General-Governor of Indochina and Loti’s close friend who had organized his 1901 trip to Angkor -, to whom he wrote: “Will you forgive me for having said that our Empire in Indo-China would lack grandeur and, more especially, would lack stability — you who have worked so gloriously and so patiently to ensure its permanence ? But so it is. I do not believe in the future of our distant colonial conquests. And I mourn the thousands and thousands of our brave little soldiers, who, before your arrival, were buried in those Asiatic cemeteries, when we might so well have spared their precious lives, and risked them only in the last defence of our beloved French land.”[p vii-viii]

Married to wealthy heiress Jeanne Amélie Blanche Franc de Ferrière — who eventually left him as he kept a mistress, Crucita Gainza [“my Basque wife”], with whom he had three children –, Loti gathered an astonishing collection of artworks, souvenirs, rarities such as sperm whale teeth, Egyptian cat mummies or Ottoman coffins, part of which is kept at the Maison Pierre Loti museum in Rochefort.

1) Julien Vaud (Pierre Loti) amongst his family in 1855 (source: gallica.bnf.fr). 2) Pierre Loti at home, c. 1892.

In his foreword to Impressions by Pierre Loti (Archibald Constable & Co., Westminster, 1898), novelist Henry James wrote: “He is extremely unequal and extremely imperfect. He is familiar with both ends of the scale of taste. I am not sure even that on the whole his talent has gained with experience as much as was to have been expected, that his earlier years have not been those in which he was most to endear himself. But these things have made little difference to a reader so committed to an affection.(…) I read and relish him whenever he appears, but his earlier things are those to which I most return. It took some time, in those years, quite to make him out he was so strange a mixture for readers of our tradition. He was a ” sailor-man” and yet a poet, a poet and yet a sailorman.(…) He has not been an explorer and is not of that race, but his perception so penetrates that he has only to take me round the corner to give me the sense of exploring. I have been assured that Madame Chrysantheme is as preposterous, as benighted a picture of Japan as if astranger, disembarking at Liverpool, had confined his acquaintance with England to a few weeks spent in disreputable female society in a vulgar suburb of that city. (…) Loti belongs to the precious few who are not afraid of being ridiculous; a condition not in itself perhaps constituting positive wealth, but speedily raised to that value when the naught in question is on the right side of certain other figures. His attitude is that whatever, on the spot and in the connection, he may happen to feel is suggestive, interesting and human, so that his duty with regard to it can only be essentially to utter it. The duty of not being ridiculous is one to which too many travellers of our own race assign the high position that he attributes to right expression, to right expression alone.(…) That is pure, essential Loti — poetry in observation, felicity in sadness.”

Two portraits of Pierre Loti at different ages [source: gallica.bnf.fr]

Publications

- Aziyadé (Stamboul 1876 – 1877) [anonym, presented as notes from an English officer killed in Turkey on 17 October 1877], 1879.

- Le Mariage de Loti [written in 1872, published with mention “par l’auteur d’Aziyadé” with the title Rarahu in 1880], 1882 [first book published by Calmann-Lévy, Paris, as well as most of the following ones].

- Le Roman d’un spahi, 1882.

- Fleurs d’ennui [short stories collection : Pasquala Ivanovitch, Suleïma, Voyage au Monténégro], 1883.

- Trois journées de guerre en Annam, 1883.

- Mon frère Yves, 1883.

- Les Trois Dames de la Kasbah, 1884.

- Pagodes souterraines, 1884.

- Pêcheur d’Islande, 1886.

- Madame Chrysanthème, 1887.

- Propos d’exil, 1888.

- Japoneries d’automne, 1889.

- Au Maroc, 1889.

- Le Roman d’un enfant, 1890.

- [preface to] Qui frappé? by Carmen Sylva, 1890.

- Le Livre de la pitié et de la mort, 1891.

- Fantôme d’Orient [derived from Aziyadé], 1891.

- Constantinople en 1890, 1892.

- Matelot, 1892.

- Discours de réception à l’ Académie française, 1892.

- L’Exilée, 1893.

- [preface to] Du côté de chez nous by Frédéric Arthur Chassériau (1865−1955), 1893.

- La Grotte d’Isturitz, 1895.

- Le Désert, 1895.

- Jérusalem, 1895.

- La Galilée, 1896.

- La Mosquée verte, 1896.

- Ramuntcho, 1897.

- Figures et choses qui passaient, 1897.

- Judith Renaudin, 1898.

- L’Île du rêve, 1898.

- Rapport sur les prix de vertu, 1898.

- [preface to] Les glanes de la vie by Comtesse Diane, Ollendorf, 1898.

- Reflets sur la sombre route, 1899.

- [preface to] Deuil de fils by Frédéric Arthur Chassériau, Ollendorf, 1899.

- [preface to] Lumières d’Orient by Émile Vedel, Ollendorf, 1901.

- Les Derniers Jours de Pékin, 1902.

- L’Inde (sans les Anglais), 1903.

- Vers Ispahan, 1904.

- [tr. with Émile Vedel] Le Roi Lear, Shakespeare, 1904.

- La Troisième Jeunesse de Madame Prune, 1905.

- Les Désenchantées, roman des harems turcs contemporains, 1906.

- Vies de deux chattes, 1907.

- Ramuntcho [theater play], 1908.

- La Mort de Philae, 1909.

- Les pagodes d’or, 1909.

- Le Château de la Belle-au-Bois-Dormant, 1910.

- Pêcheur d’Islande [theater play], 1911.

- La Fille du ciel, drame chinois [theater play with Judith Gauthier], 1911.

- [preface to] Poésies d’un marin by Eugène de Fauque de Jonquières, 1911.

- Un pèlerin d’Angkor, 1912; English ed.: Siam, translated from the French by W. P. Baines, illustrated with photographs and an etching by Edith M. Hinchley, T. Werner Laurie Publishers, London, 1913, and Philadelphia, David McKay, 1914; reissued 1930, with illustrations by F. de Marliave, Paris, Henri Cyral.

- [preface to] Les deux rêves by Justin Massé, 1912.

- Turquie agonisante, 1913.

- La Grande Barbarie, 1915.

- À Soissons, 1915.

- La Hyène enragée, 1916.

- Quelques aspects du vertige mondial, 1917.

- L’Outrage des barbares, 1917.

- Court intermède de charme au milieu de l’horreur, 1918.

- L’Horreur allemande, 1918.

- Les Massacres d’Arménie, 1918.

- Les Alliés qu’il nous faudrait, 1919.

- Mon premier grand chagrin, 1919.

- Prime Jeunesse, 1920.

- La Mort de notre chère France en Orient, 1920.

- Suprêmes visions d’Orient [with son Samuel Viaud], 1921.

- Un jeune officier pauvre [extracts of P.L.‘s journal published by Samuel Vaud], 1923.

- Journal intime, 1878 – 1881, 1st part, [also series in L’Illustration], 1925.

- La maison des aïeules suivi de Mademoiselle Anna très humble poupée, illustr. by André Hellé, 1927.

- Journal intime, 1882 – 1885, 2d part, 2 vol. with unpublished letters 1865 – 1904, 1929 [posthumous]; reiss. as a)

Cette éternelle nostalgie, journal intime, extraits (1878−1911), Paris, La Table Ronde, 1997; b) Soldats bleus, journal intime, 1914 – 1918, Paris, La Table Ronde, 1998. c) Unabridged edition: Journal intime 1868 – 1878, t. I, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, Paris, Les Indes savantes, 2006; Journal intime 1879 – 1886, t. II, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, id., 2008; Journal intime 1887 – 1895, t. III, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, Paris, id., 2012; Journal intime 1896 – 1902, t. IV, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, id., 2016; Journal intime 1903 – 1913, t. V, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, id., 2017.