Visions of Angkor Park Preservation by...Lim Bunhong

by Bunhong Lim

Working with nature, not against it: the task of maintaining Angkor Archaeological Park, now 100-year old, and the women and men behind it.

- Published

- 2025

- Author

- Bunhong Lim

- Source

- courtesy of the author.

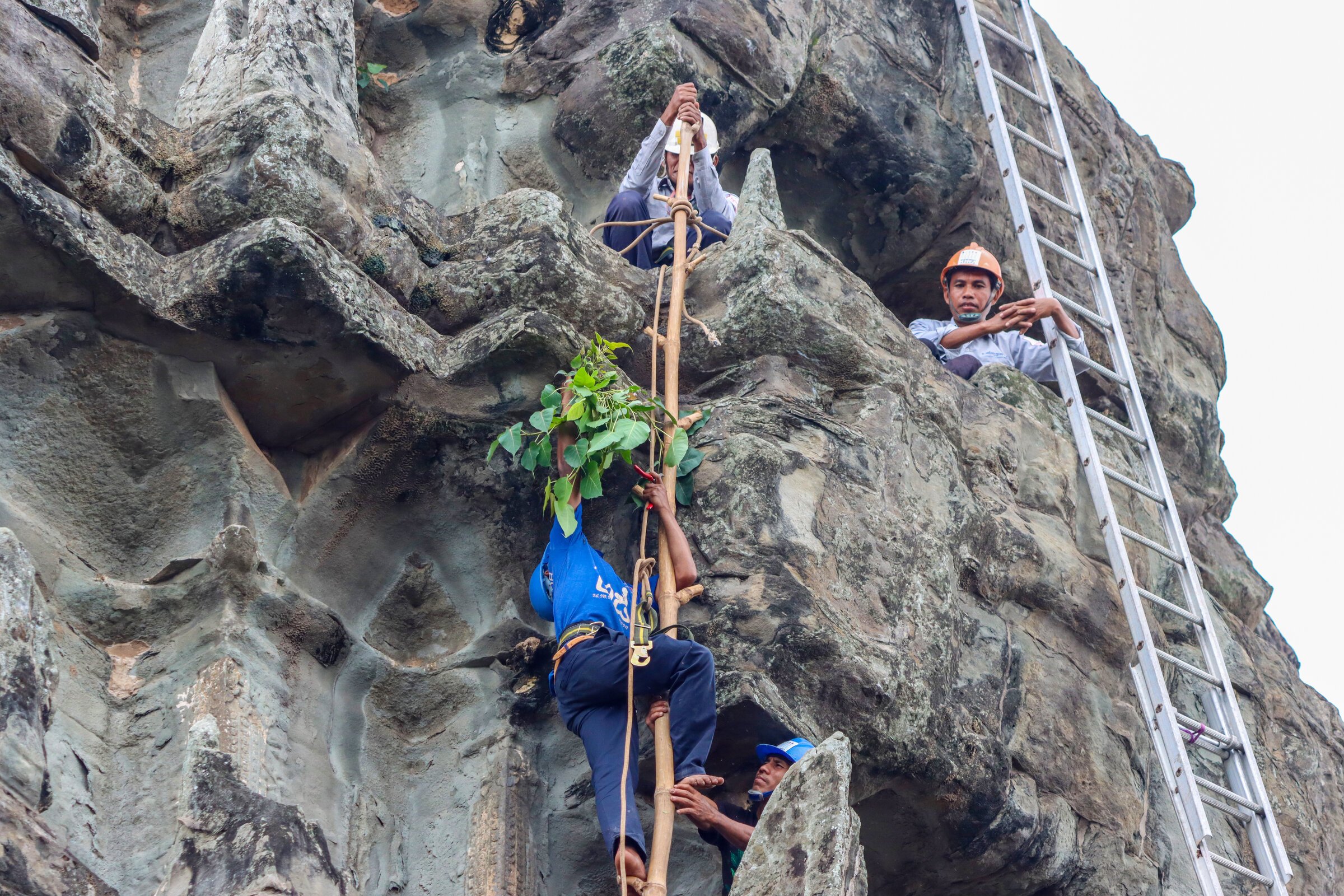

Across 400 square kilometers (about 154 square miles), the maintenance and preservations teams of APSARA Authority and, in the last decades, various service companies under contract, are each and every day at work to keep Nature at bay from hundreds of temples and monuments in a non-aggressive, eco-responsible way. Photographer Lim Bunhong has documented this effort for over two years, from acrobatic prowess when reaching the upper structures to the humble yet essential task of keeping the numerous bodies of water clear of invasive vegetation.

One century ago, the Parc archéologique d’Ankor (Angkor Archaeological Park) was officially instituted (30 Oct. 1925 “Arrêté” [Decree] published in Journal Officiel, 1925, p. 2347, with additional decreed on 16 December 1926 and 30 September 1929 and 21 May 1930, “instituting the Angkor Park and setting its boundaries). Much has been written about the ‘romantic-colonial’ notion of landscaping a “paysage ruiné” [landscaped ruins] — the term was coined by explorer Louis Fournereau — around the Khmer temples at Angkor. At the same time, the French administators reckoned the existence of “historic villages” across the whole area, a population ancestrally attached to the ruins.

The formidable task of maintaining the area, making the temples accessible to international tourism and, increasingly since the 2020 – 2022 pandemic, Cambodian visitors, and preserving monuments and ponds from invasive vegetation, is directly in the hands of the workers we see in this photo-gallery. Even if in recent years some heavy machinery has been used, in particular for trimming the majestic trees in the park — submitted to harsher climatic conditions to global warming -, their daily effort remains mostly by hand, quietly, out of respect for the historic structures and their symbolic significance.

At the Edge of the Forest

Clearing the temples summarizes the very essence of the Angkorian complex: it is a man-made creation surrounded by and immerged into the remains of primeval forest. Vegetation growth symbolizes the power of nature, and for Cambodian people nowadays there is this essential, profoundly Buddhist urge “to go see the ruins in the forest,” and to meditate on the transient human endeavors. Incidentally, the Buddhist Center of Cambodia ពុទ្ធមណ្ឌលកម្ពុជា built in Kandal in 1996 is set within a landscaped area ofabout 107 hectares.

Since its integration to modernity at the end of the 19th century, Angkor is first and foremost about how to leave the monuments in their natural context without leaving them to it. Suffice to read the first major report on the archeological site of Angkor, written by Orientalist Édouard Chavannes (1865−1918) and Claude Eugène Maitre (1876 — 1925, director of EFEO until 1920 with long interims by Henri Parmentier and Louis Finot) after their Dec.1907-Jan.1908 mission:

Grâce à l’énergique direction de M. Commaille, le débroussaillement avait déjà fait des progrès considérables au commencement de l’année 1908 ; sous le couperet des bûcherons cambodgiens, des pans de brousse s’abattaient chaque jour et jonchaient le sol où on les laissait sécher jusqu’au moment où on pourrait les détruire par le feu. Le Bayon était entièrement dégagé; la place qui s’étend devant la terrasse ornée d’éléphants en bas-relief était en grande partie débarrassée de la végétation exubérante qui l’obstruait et on pouvait se rendre compte des perspectives admirables qu’on aurait lorsque , de ce point central, on apercevrait tout autour de soi les principaux monuments d’Angkor-Thom. Il faudra encore percer quelques larges avenues qui traversent la ville de part en part, arracher dans les interstices des pierres les racines des arbres qu’on s’est contenté jusqu’ici de couper à la base, enfin exercer une surveillance incessante pour que le terrain conquis par le défrichement né soit pas pas envahi de nouveau par les rotins épineux et par les lianes.

Thanks to Mr. [Jean] Commaille’s energetic leadership, the clearing of the undergrowth had already made considerable progress by the beginning of 1908; under the axe of the Cambodian woodcutters, sections of bush fell daily and littered the ground where they were left to dry until they could be destroyed by fire. The Bayon was entirely cleared; the area extending in front of the terrace adorned with bas-relief elephants was largely freed from the exuberant vegetation that obstructed it, and one could imagine the admirable vistas that would be afforded when, from this central vantage point, one could see all around the principal monuments of Angkor Thom. It will still be necessary to create some wide avenues that cross the city from one end to the other, to pull out the roots of the trees in the crevices of the stones, which until now have only been cut at the base, and finally to exercise constant surveillance to ensure that the land conquered by clearing is not invaded again by thorny rattan and vines. (Bulletin de la Commission Archeologique de l’Indochine (BCAI), Paris, 1908, p 13 – 4).

When the area slowly recovered from the civil war in the early 1980s, the clearing effort had to be deployed again, mostly at the active involvement of the local population:

Many local villagers worked with French conservators for the Angkor Conservation Office and are skilled conservation labourers. Generations of conservators are proud of their family tradition. Many of the senior local monks and abbots used to be conservation labourers. Some villagers also began voluntarily to clean Angkor temples and vihears (vihara or temple hall) in the 1980s, prior to the reorganization of maintenance work in the site by the Cambodian authorities. [Special Issue: World Heritage in Cambodia, World Heritage 68, June 2013, p 28.]

Even in the 1990s, all APSARA activity reports dealing with conservation, mostly in French, started with “Phase 1, débrouissallage” [Phase 1: Clearing]. This patient work combined with initiatives in monuments’ restoration and development of renewed archaeological projects led to the removal of Angkor from the World Heritage List of Endangered Sites in 2004.

Nowadays, APSARA National Authority works again with cleaning companies to ensure the cleaning and maintenance of the area. HCC, a private cleaning company whose uniforms can be seen on these photography, has been replaced by VGreen, part of the Cambodian company Sonavith, employing in 2025 some 551 workers, 80 pc of them women. APSARA technical services are in charge of the clearing of the monuments proper, and coordinate with the Forest Research Institute of India (FRI) for the conservation and maintenance of large trees.

A Living Site

The 114 recognized ‘historic villages’ within the Angkor boundaries, and the strong attraction to the temples by the whole country, make it a unique archeological park. New needs for roads, parking areas, tourist infrastructure, are to be balanced with the committment to resist the real estate pressure, ensure an harmonious interaction between the park and its connected city, Siem Reap, and preserve the spiritual significance of the temples.

The already quoted Word Heritage report stated in 2013 that

The number of residents living in protected zones is increasing exponentially. Since the return of peace and stability to the kingdom, large numbers of villagers have moved from less prosperous areas to settle in Angkor Park to make a living from tourism in that area. Although the average birth rate in the country was only 3.1 per cent from 1992 to 2009, the increase brought about by migration combined with births is 9. 5 per cent. The principal data on population growth in Angkor Park are as follows:

- census by United Nations mission in 1992: 22,000 residents;

- national census in 1998, 84,000 residents: APSARA census in 2005, 100,000 residents (18,500 families);

- estimation for 2010, 120,000 residents (21,500 families).

“Although each resident has the right to an average of 1 ha of agricultural land, annual rice production is still insufficient for family consumption levels, especially in September and October.” Various jobs have been added to agricultural activities, “mainly collecting firewood (27 per cent), cultivating rice (20 per cent), other activities such as employment within the APSARA National Authority — guardians of monuments, manoeuvres, maintenance workers (36 per cent), or unskilled jobs (17 per cent). Most families, about 60 per cent, are poor. According to a 2007 study, the average monthly income per resident was US$24- 30. [Special Issue: World Heritage in Cambodia, op. cit., p 29.]

The images of people at work we present here reflect Angkor’s unique character is to be found in the combination of “people, forests and stones”, as aptly summarized by Australian Conservationist Rowena E. Butland, who remarked that APSARA (and less directly ICC-Angkor, the International Coordinating Committee for the Safeguarding and Development of the historic site of Angkor, created on 13 October 1993 to “ensures the coordination of the successive scientific, restoration and conservation related projects, executed by the Royal Cambodian Government and its international partners”)

saw a synergy between the people, forests and stones. They were caught between conflicting temporal constructions of a traditional scale of interpretation and a contemporary scale of, but they recognised that the people are not going anywhere, so the two constructions must be sympathetically aligned. For APSARA, a landscape interpretation of Angkor is perhaps the only way of incorporating these varied perspectives. [Rowena Emily Butland, Scaling Angkor: Perceptions of Scale in the Interpretation and Management of Cultural Heritage, doctoral thesis, School of Geosciences, The University of Sydney, July 2009, p 187]

The pursuit of the right balance between cultural preservation with community development is ongoing. Since 2022, the policy aiming at voluntarily relocating the Park’s residents who had moved there after 2004 to two new communes, Run Ta Ek and Peak Sneng, has generated discussions. In May 2025, government officials and heritage authorities reached a draft agreement on land use terms for the Angkor Archaeological Park, resulting in a “Angkor White Book” that might be made public soon at the time of this writing.

Seeing the photographs of maintenance and cleaning workers at work is a reminder that Angkor Archaeological Park stands apart in the list of major archeaological sites. In comparison, the Borobudur Temple Compounds (8th and 9th centuries, Sailendra Dynasty) in Indonesia covers a surface area of 2,520 m² with 72 openwork stupas around the central structure, each containing a statue of the Buddha, and the “touristic villages” around are set apart from the site proper. The Pompeii Archaeological Park covers an area of only 66 hectares (0,6 sqkm), of which a smaller part already excavated is accessible to visitors. The Machu Picchu Archaeological Park (Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu), has a size about 325 sqm, yet the “Lost City” itself is approximately 0,1 ha, and so far removed from the main urban center nearby that tourist road and railway transfers is often disturbed.

Tags: preservation, flora, Angkor Archaeological Park, nature preservation, biodiversity, maintenance, Apsara Authority, tourism

About the Photographer

Bunhong Lim

Lim Bunhong (b. 4 May 1983, Siem Reap) is a Cambodian independent photographer who has extensively covered the teamwork on the conservation of Angkor Archaeological Park monuments as a technical officer at the Department of Monuments Conservation, APSARA Authority since 2020.

With a MD in Education (2013) and a BA in Tourism & Hospitality Management (2006) at Build Bright University, Siem Reap, Bunhong has worked as a teacher, a sales representative and surveyor in the tourism industry, pursuing his passion for photography during spare time. He was an assistant to the management of Angkor Training Center in 2020, which helped him to know better the daily work of APSARA and HCC Group (environment services) teams.

In 2023, he launched NagaEyes KH, a Facebook page showcasing his photographic work, and in November 2024 held his first solo exhibition, part of the Siem Reap edition of Phnom Penh Photo Festival. One of his photos was the background of the festival 15h edition poster.

Bunhong is currently developing an intimate, intensely focused photographic study on various Angkorian temples and monuments, from Banteay Chhmar to Beng Maelea, and intends to publish books devoted to each one. Under his lens, reliefs and statues of Banteay Srei, for instance, gain a remarkable vividness, as he carefully uses the variations of daylight on the stone. He is also completing panoramic photographs of all the galleries of Angkor Wat, a technical feat allowing the reliefs to be revealed in all their splendor.

In his vision, men and women at work on the temples or living in their shadows, natural wonders around them, and the fragile beauty of ancient artworks, all become united into what makes the Angkor site completely unique. And he celebrates the ongoing effort “to prevent the decay of sculptures thanks to the restoration work by national and international experts”, as reflected by this November 2024 photo of a relief at Angkor Wat: