Hermann Kulke

Hermann Kulke (b. 1938, Berlin) is a German historian and Indologist, a former professor of South and Southeast Asian history at the Department of History, Kiel University (1988 – 2003).

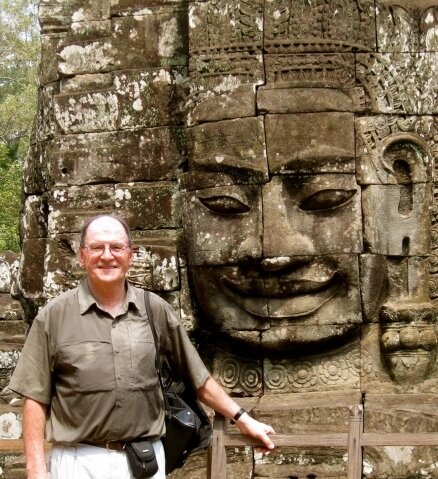

After receiving his PhD in Indology from Freiburg University in 1967, he taught for 21 years at the South Asia Institute of Heidelberg University (SAI).He was a founding member of the Orissa Research Project (ORP) of the Southasia Institute (1970 – 1975), and was coordinator of the second ORP.Specialization: pre-colonial South and Southeast Asian History. He initiated his comprative studies on South and Southeast Asian (Cambodia and Indonesia in particular) cultures with his 1975 thesis ‘Jagannatha Cult and Gajapati-Kingship. A Contribution to the History of Religious Legitimation of Hindu Rulers.’

Based in Odisha (Orissa) for many years, he studied the cult of local tribe goddesses and the Tamil Nadu form of Puri celebrations. In a 2019 interview led by Prof. Bhairabi Prasad Sahu (Department of History, University of Delhi), historian and cultural heritage researcher Dr Yaaminey Mubayi, and Meenakshi Vashisth (research coordinator at Sahapedia.org, Prof. Kulke commented:

My studies on Southeast Asia, particularly on Indonesia and Cambodia, influenced and enriched my understanding of Indian history in many ways. In the early twentieth century, the famous German sociologist, Max Weber, referred to the important role of inviting north-Indian Brahmins to validate the newly acquired authority of South Indian chieftains and little kings. In 1934, the Dutch scholar van Leur applied this thesis to processes of early Hinduisation and state formation in Java. Referring in detail to van Leur’s Javanese studies, I applied his Javanese concept of legitimation to India, and to Odisha in particular. A detailed analysis of Indonesia’s earliest Sanskrit inscriptions (from the early fifth century) depict a high accordance with eastern and southern India. Once we look at the societies on both sides of the Bay of Bengal in this way, we understand that India’s culture did not reach Southeast Asia by an act of transplantation but through a complicated convergence of processes of state formation from both sides of the Bay of Bengal.

Comparing the Gajapati kingship of Odisha and the Devaraja kingship of Angkor, he noted that this was

the subject of my second Qureshi Memorial Lecture on January 18th. The Devaraja cult centres around a Siva lingam on Phnom Kulen, about 40 km north-east of Angkor. It was founded in 802 CE in a grand ceremony, known as the kamratenjagat ta raja (=devaraja), by an Indian Brahmin who had been invited by King Jayavarman II. A detailed inscription informs us that the Devaraja was consecrated, and ‘that there should be only one single “Lord of the lower earth” (Khmer: kamratenphdaikarom) who would be Universal Lord (cakravartin)’. The Devaraja cult and its interpretation have caused much ink to flow primarily because, according to the rules of Sanskrit grammar, ‘devaraja’ allows two very different interpretations: ‘the king who is the god’ and ‘the king of the gods’. It was particularly George Coedès, the doyen of Angkor historians, who fought vehemently for the first interpretation and, thus, for the deification of Angkor’s kings. He concluded from the evidence that it was safe to say that the kings were the great gods of ancient Cambodia, to whom lingams were dedicated in the temples at Angkor, to idolise their builders as the deified devarajas.

It is fascinating to have a look at the convergence of kingship ideology and monumental temple architecture in Odisha and Angkor during the culmination of their imperial state formation. It has rarely been perceived that their unique monumental temples (the Jagannath Temple and the Sun Temple in Odisha, and Angkor Wat and the Bayon at Angkor) were built contemporaneously in the eleventh and the thirteenth centuries.

After my dissertation on Chidambaram, I was still interested in the kingship ideology of the Cholas and their imperial temple at Thanjavur. I had, therefore, initially planned to write a comparative study of Chola kingship ideology and Angkor’s Devaraja cult as my DLitt thesis. After all, Thanjavur’s truely monumental rajarajesvaralingam stands likewise either for ‘[Siva] the Lord of [king] Rajaraja’ or for ‘Rajaraja, the Lord’, thus deifying Rajaraja. In 1969 and early 1970, I participated therefore in intensive language courses in spoken and classical Khmer (the language spoken in Cambodia) at Yale University and the School of African and Oriental Studies (SOAS) in London. A critical analysis of the relevant Sanskrit and Khmer inscriptions, and more recent studies on the Devaraja cult, confirmed my serious doubts about two key issues of Coedès’ interpretations of the Devaraja cult. These doubts concerned his equation of the divine Devaraja with the ruling kings of Angkor, and the idea that the Devarajas were worshipped through the irrespective personal lingams. These doubts were further confirmed by my studies in Odisha. Although the Gajapati kingship ideology raised the dignity of the rulers considerably and brought them closer to a divine sphere, they were never identified with their istadevatas or kuladevatas.

Another significant ‘discovery’ in Odisha for my studies on Angkor’s Devaraja cult was the calantipratimas — the ‘mobile images’ of stationary deities of temples. I remember very well my first observation of the ratha yatra of the Lingaraja Temple at Bhubaneswar. A beautiful old bronze image of Siva was worshipped on the ratha as the representative of the lingaraja, Siva’s lingam in the temple. Calantipratimas are particularly required for lingams as it is well known that ‘a Sivalinga may not be moved’ (sivalingamnacalayet). Although Bhubaneswar’s lingaraja is certainly not identical to Angkor’s Devaraja cult, their comparison is doubtlessly helpful for our understanding of the latter. On the basis of the ritual necessity of a calantipratima for the Lingaraja cult, I came to the obvious but still conjectural conclusion that the rituals of the fundamentally important Devaraja cult, too, required a calantipratima of its original foundation lingam on far-off Phnom Kulen. However, the bronze image of Siva-Devaraja did not represent Angkor’s ruling kings but Phnom Kulen’s Siva lingam. My ‘discovery’ in Odisha of the ritually significant function of the calantipratima of the central lingam of Siva temples formed an essential argument to refute the deification of Angkor’s kings as Devarajas.

Udayadityavarman II founded the Baphuon, Angkor’s last monumental Siva temple associated with the Devaraja cult, in the second half of the eleventh century. In one of his inscriptions we find a significant depiction of the ideological significance of royal lingams, not only in Angkor but also in India. We are told that he erected the suvarnadri or ‘golden mountain’ (the Baphuon) in his own city, which was comparable to Mount Meru, the abode of the gods. On the summit of this golden mountain he consecrated asuvarnalinga (golden lingam). A victorious general sought Udayadityavarman’s permission to donate his spoils of war to this golden lingam, which harboured in itself the ‘subtle inner self’ (suksma-antara-atman) of Udayadityavarman. Here, we find in a few lines, paradigmatically also for Indian studies, the very essence of the apotheosis of the rulers of Angkor. The ‘subtle inner self’ of the king dwells in a lingam which the king had consecrated as a symbol of his power, during the course of his reign. As the kings of Angkor are often also exalted as a portion (amsa) of Siva, it appears that this ‘portion’ and the ‘subtle inner self’ of the kings are identical. Hence, Siva and the kings of Angkor were united in a lingam upon the topmost step of a temple pyramid. It constituted the ritual centre of the Angkorian kingdom and represented a microcosmic replica of Mount Meru. But despite his ritual merging with Siva, the ruling king of Angkor was neither the Devaraja nor even Siva himself, but anamsa of him. This insight into Angkor’s kingship ideology influenced my DLitt in 1975. However, it was not, as initially planned, a comparative study on Chola kingship ideology and Angkor’s Devaraja cult, but dedicated to the cult of Jagannath and Gajapati kingship.

Publications

- ‘Cidambaramāhātmya: A critical examination of the priestly traditions of a South Indian temple city with regard to its religious and historical development’, PhD thesis, Freiburg University, 1967.

- ‘Jagannatha Cult and Gajapati-Kingship. A Contribution to the History of Religious Legitimation of Hindu Rulers.’ DLitt thesis, Heidelberg University, 1975.

- [ed with Anncharlott Eschmann and Gaya Charan Tripathi], The Cult of Jagannath and the Regional Tradition of Orissa. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors, 2014 [First published in 1978].

- ‘The Devaraja Cult’, In Kings and Cults: State Formation and Legitimation in India and Southeast Asia, 327 – 382. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors, 1993.

- The State in India, 1000 – 1700. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- [ed. with K. Kesavapany and Vijay Sakhuja], Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Singapore, ISEAS-YII, 2009. ISBN 9789812309389.

- [ed. with Georg Berkemer], Centres out There?: Facets of Subregional Identities in Orissa. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors, 2011.

- [ed. with Sahu, Bhairabi Prasad], Interrogating Political Systems: Integrative Processes and States in Pre-modern India. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors, 2015.

- [with Dietmar Rothermund], A History of India, 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2016.

- ‘Śrīvijaya Revisited: Reflections on State Formation of a Southeast Asian Thalassocracy’, BEFEO 102, 2016, pp. 45 – 95.

- History of Precolonial India: Issues and Debates. Edited by Bhairabi Prasad Sahu. Translated by Parnal Chirmuley. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- ‘Imperial Temple Architecture and Ideology of Kingship in Odisha: Tanjavur’s Brihadisvara Temple as the Model for Odisha’s Monumental Temples?’ In Questioning Paradigms Constructing Histories. A Festschrift for Romila Thapar, edited by Kumkum Roy and Naina Dayal, 87 – 108. New Delhi: Aleph Book Company, 2018.