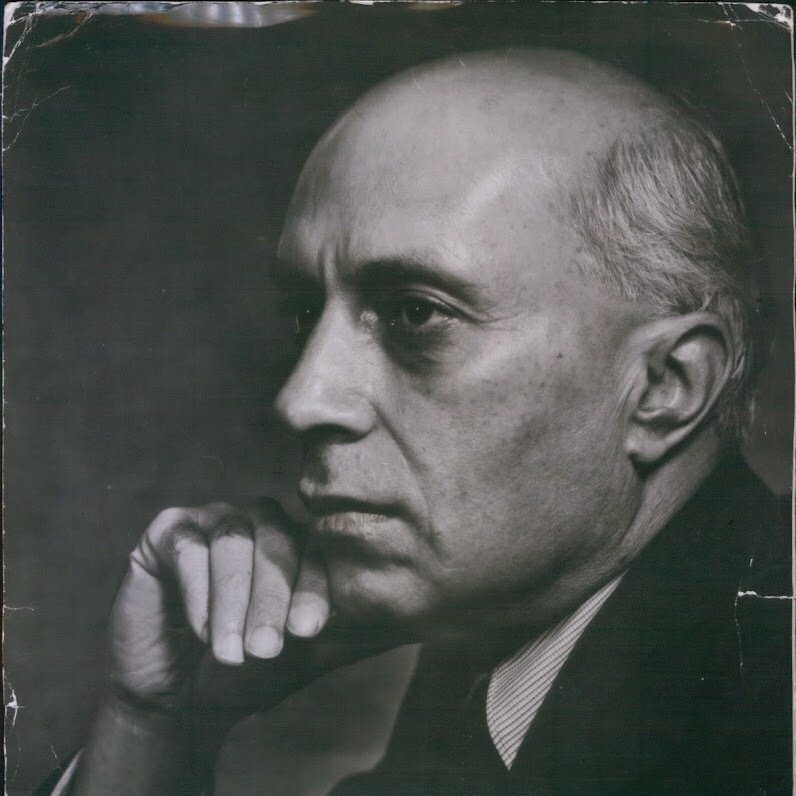

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru, Pandit Nehru (14 Nov. 1889, Allahabad, India — 27 May 1964, New Delhi) was an Indian anti-colonial activist and statesman, the figure head leader of the Indian nationalist movement in the 1930s and 1940s, the first Prime Minister of independent India from 1947 to his death in 1964, and a renowned literary author and speaker (mostly in English but also in Hindi). He promoted parliamentary democracy, secularism, science and technology during the 1950s.

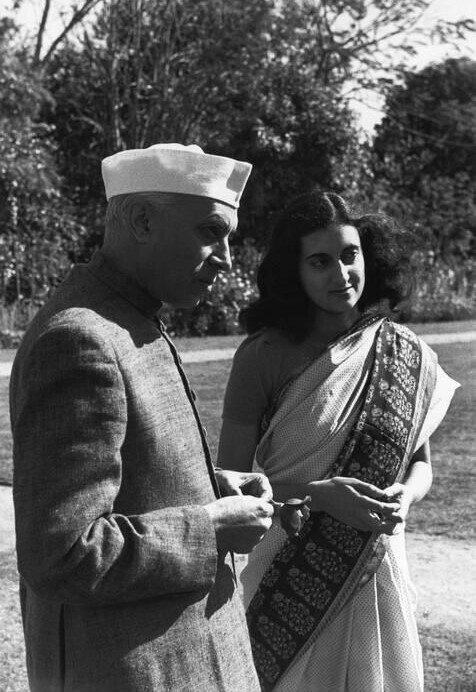

The son of Motilal Nehru, a prominent lawyer and Indian nationalist, JL Nehru was educated in England — at Harrow School and Trinity College, Cambridge, becoming a barrister and joining the Indian National Congress in the 1920s. Designated by Mahatma Gandhi as his political heir, he fought for independence since 1929, spending years in British jails, the last imprisonment lasting 1,041 days and ending on June 15, 1945. His sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, was herself a noted figure of the independist movement.

As a child, he heard mythological tales and stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata from his mother and aunts, and tales of great Revolt of 1857. During his many years in jail for his anti-colonialist stance, he was supported by his wife, Kamala Nehru, one of the first Indian feminist and social-rights activist. He met with Gandhi for the first time in December, 1916, in Lucknow.

An agnostic with a strong belief in India as a national identity, Nehru became a prominent advocate of neutralism and non-violence, a leader of the “non-aligned” countries during the Cold War. His ambition to reach a permanent peace settlement with China was marred by Chinese attacks on Sikkim and Tibet. His policy towards China evolved from the 1954 openings to him being “trapped in Indian nationalism, which forced him away from his principles into a disastrous war, and saw his policies collapse around him.” [cf. Michael Brecher, Political Leadership and Charisma: Nehru, Ben-Gurion, and Other 20th Century Political Leaders, Al Odyssey I, Palgrave-McMillan, 2016, ISBN 9783319326276, p 100]

A visionary leader, Nehru was adverse to any ideological or religious involvement, even if he had been close to Fabian socialism (George Bernard Shaw) during his formative years. “Religion, as I saw it practiced, and accepted even by thinking minds, whether it was Hinduism or Islam or Buddhism or Christianity, did not attract me. It seemed to be closely associated with superstitious practices and dogmatic beliefs, and behind it lay a method of approach to life’s problems which was certainly not that of science … Essentially I am interested in this world, in this life, not in some other world or a future life.” [quote from his obituary in New York Times, 28 May 1964, “Nehru, a ‘Queer Mixture of East and West,’ Led the Struggle for a, Modern India; DEVOTED HIS LIFE TO NATION’S CAUSE; Blended Skill in Politics With the Spiritualism of His Mentor, Gandhi.”]

In his Will and Testament [doc. SWJNS2V26P612/13], penned on 21 June 1954, a few months before his trip to China and Indochina — including a visit to Cambodia, the first head of State visiting the Kingdom since its independence in 1953 -, Nehru wrote:

When I die, I should like my body to be cremated. If I die in a foreign country, my body should be cremated there and my ashes sent to Allahabad. A small handful of these ashes should be thrown into the Ganga and the major portion of them disposed of in the manner indicated below. No part of these ashes should be retained or preserved. My desire to have a handful of my ashes thrown into the Ganga at Allahabad has no religious significance, so far as I am concerned. I have no religious sentiment in the matter. I have been attached to the Ganga and the Jumna rivers in Allahabad ever since my childhood and, as I have grown older, this attachment has also grown. I have watched their varying moods as the seasons changed, and have often thought of the history and myth and tradition,and song and story, that have become attached to them through the long ages and become a part of their flowing waters. The Ganga, especially, is the river of India, beloved of her people, round which are intertwined her racial memories, her hopes and fears, her songs of triumph, her victories and her defeats. She has been a symbol of India’s age-long culture and civilization, ever-changing, ever-flowing, and yet ever the same Ganga. She reminds me of the snow covered peaks and the deep valleys of the Himalayas, which I have loved so much, and of the rich and vast plains below, where my life and work have been cast. Smiling and dancing in the morning sunlight, and dark and gloomy and full of mystery as the evening shadows fall, a narrow, slow and graceful stream in winter, and a vast roaring thing during the monsoon, broad-bosomed almost as the sea, and with something of the sea’s power to destroy, the Ganga has been to me a symbol and a memory’ of the past of India, running into the present, and flowing on to the great ocean of the future. And though I have discarded much of past tradition and custom, and am anxious that India should rid herself of all shackles that bind and constrain her and divide her people, and suppress vast numbers of them, and prevent the free development of the body and the spirit; though I seek all this, yet I do not wish to cut myself off from that past completely. I am proud of that great inheritance that has been, and is, ours, and I am conscious that I too, like all of us, and a link in that unbroken chain which goes back to the dawn of history in the immemorial past of India. That chain I would not break, for I treasure it and seek inspiration from it. And as witness of this desire of mine and as my last homage to India’s cultural inheritance, I am making this request that a handful of my ashes be thrown into the Ganga at Allahabad to be carried to the great ocean that washes India’s shore.

In the 2020s, Nehru’s figure surged back into the Indian political discussion, with Hindu nationalists blaming “Nerhuvian socialism.” In 2023, a fake AI photograph of Prime Minister Narendrah Modi paying his respect to Nehru’s statue — it was in fact Mahatma Gandhi’s statue — ignited some heated discussions in India.

Publications

- Toward Freedom/An Autobiography, 1936

- Glimpses of World History

- One Nation, One Heart

- India and the World

- Soviet Russia

- Letters from a Father to his Daughter, 1929

- China, Spain and the War

- The Unity of India

- Whither India

- Eighteen Months in India

- Recent Essays and Writing, Allahabad, 1934

- An Autobiography, 1936

- Independence and After

- The Discovery of India, 1946

- A Window in Prison and Prison Land