Five Years in Siam, From 1891 to 1896, Vol II

by Herbert Warington Smyth

A remarkable 1890s account of the Siamese, Cambodian and Laotian societies, geographical surveys and mining explorations.

- Formats

- e-book, ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- London, John Murray, London.

- Edition

- 1) Elibron Classics Facsimile, Adamant Media Corporation, Monee, IL., USA, 2005 | 2) digital version Google Books

- Published

- 1898

- Author

- Herbert Warington Smyth

- Pages

- 337

- ISBN

- 054399418X

- Language

- English

pdf 18.4 MB

A British mining inspector, the author extensively prospected the underground resources of the Malay Peninsula, South Siam and Cambodia, in particular in the Battambang area.

While the first volume had focused on Laos and Siam — he obviously got much information from Prince Damrong (then Minister of Education, and later of Interior), who contrary to other Siamese intellectuals was ready to acknowledge the importance of the Khmer cultural legacy –, these chapters gave us interesting insights on Angkor under the Siamese rule, the Tonle Sap Lake, mining in the ‘Cambodian Peninsula’and the development of international trade and exports at the turn of the century.

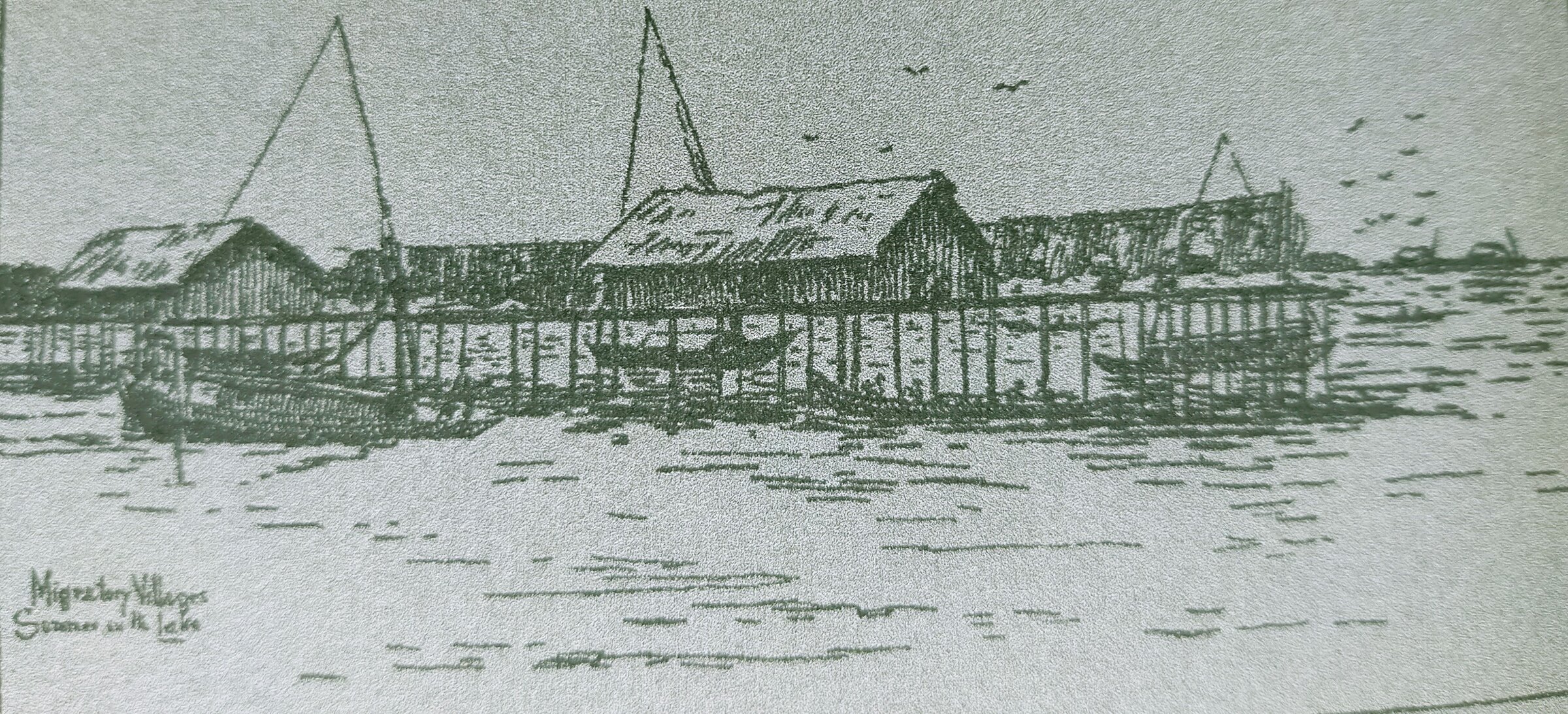

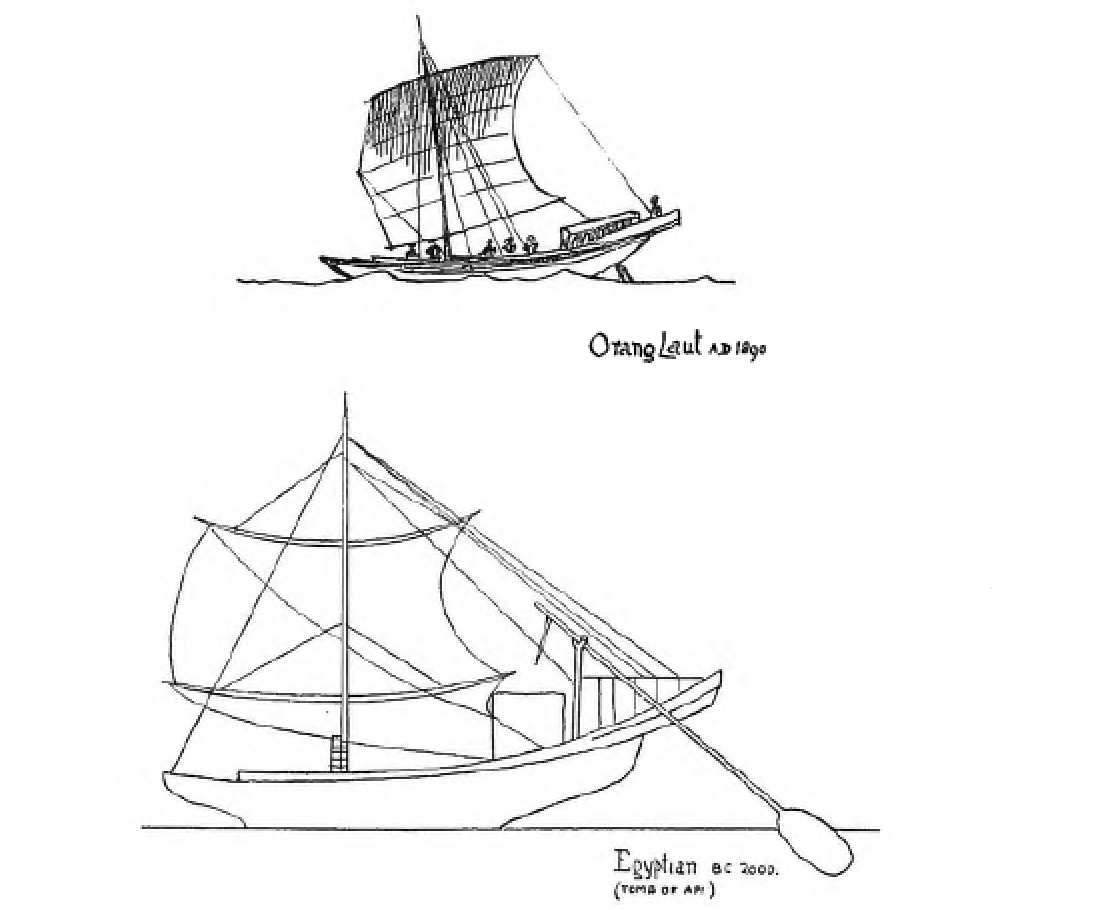

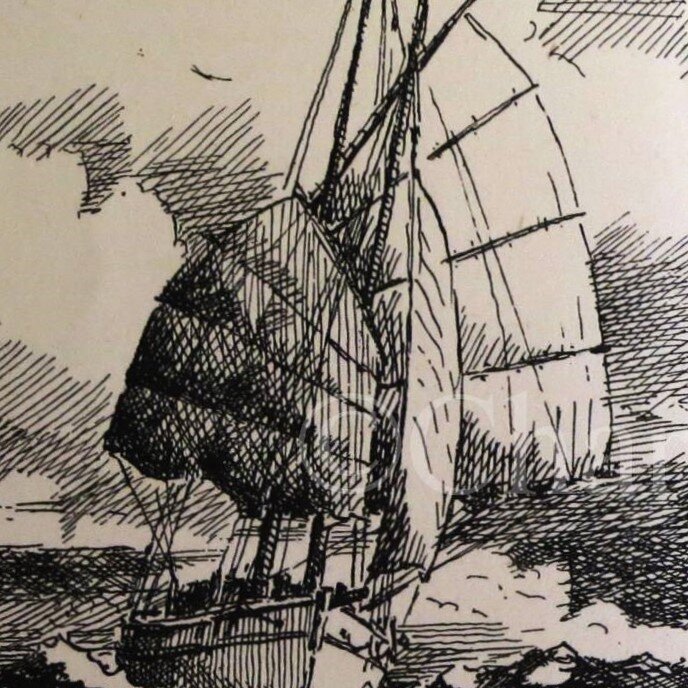

1) ‘Migratory Villages, Siamese on the Lake’, drawing by the author. 2) An accomplished yachtsman himself, Warington-Smyth also draw several types of boats in use in the area, claiming that their built was closer to Egyptian than Greek vessels. Here, he compared a Malay orang laut with a depiction of boat found in the tomb of Egyptian King Api.

1) ‘Migratory Villages, Siamese on the Lake’, drawing by the author. 2) An accomplished yachtsman himself, Warington-Smyth also draw several types of boats in use in the area, claiming that their built was closer to Egyptian than Greek vessels. Here, he compared a Malay orang laut with a depiction of boat found in the tomb of Egyptian King Api.

1) ‘Migratory Villages, Siamese on the Lake’, drawing by the author. 2) An accomplished yachtsman himself, Warington-Smyth also draw several types of boats in use in the area, claiming that their built was closer to Egyptian than Greek vessels. Here, he compared a Malay orang laut with a depiction of boat found in the tomb of Egyptian King Api.

Angkor

The rude French visitors of Angkor: ‘[A considerable amount of pilgrims from Korat] complained bitterly about the treatment they received at the hands of French visitors coming to the Wat by the lake steamers from Cambodia, of whom seventy or eighty arrive every year. They cut their names all over the ruins, and are surly and domineering to the [resident] monks, demanding little pras, or images, to take away as curios, and cursing and even striking them if they are not satisfied.’ (p 235)

About the derelict state of the ruins: ‘A kindly brave old [pilgrim] lady broke out on the squatting monks in vehement abuse: “If we Gulas had such a Wat as that to tend, we should not let the bats and jungle deface it as you do. What do you do here? Do you call it making merit sitting and doing nothing?’ (p 236)

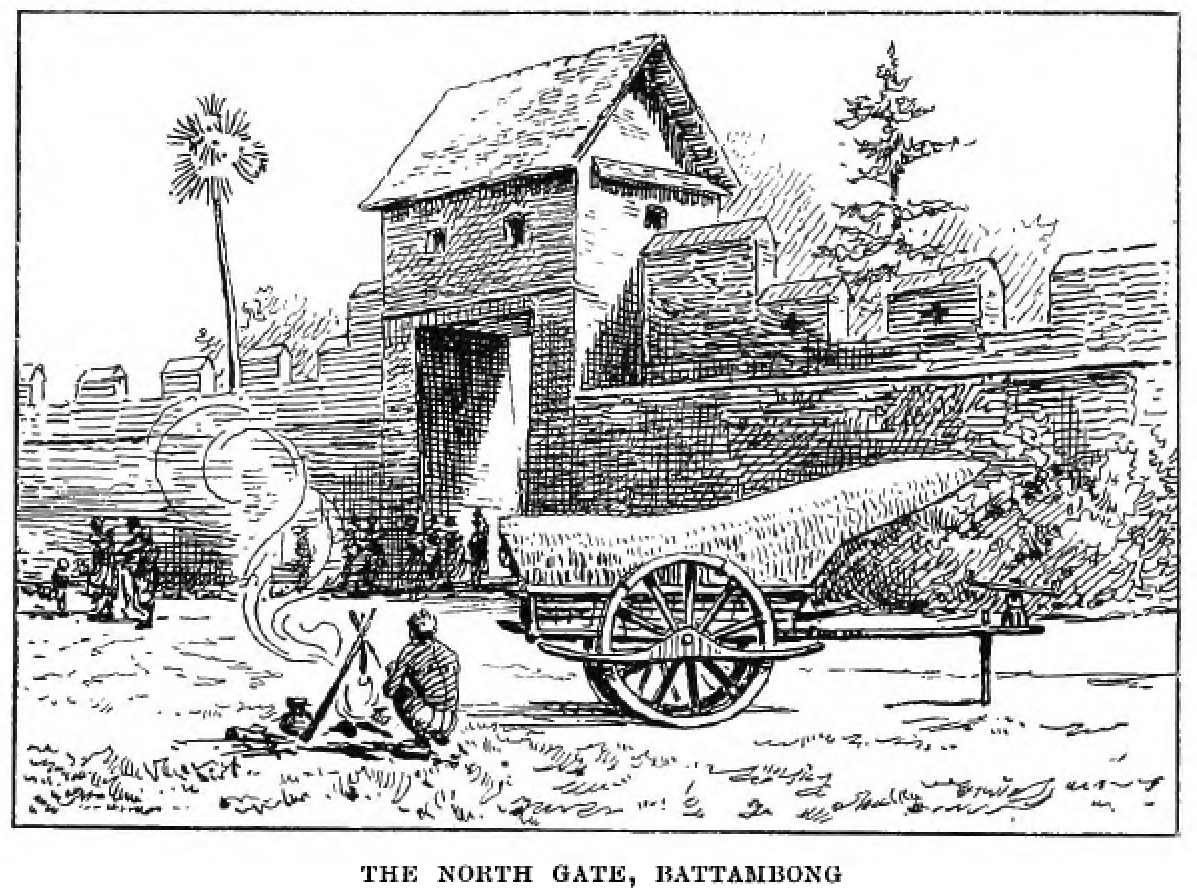

Battambang and Siem Reap between Siam and France

Here, we assess a question that has been recurrent for many decades: did the Siamese power build actual ‘citadels’ or ‘fortresses’ in Siem Reap and Battambang, or was the Kampeng [kh កំពង់ , th กัมปง, probably from Malay kampung, ‘enclosure’, ‘village-embankment’. The author noted: “This word is obviously the same as the Malay Kampong, but the Siamese have, as is usual, put the accent on the last syllable, which gives it a very different

sound”[p. 222]] mentioned by several authors since Etienne Aymonier was merely a fortified wall (with outposts) built around part of the city?

‘The whole plain, in the lower parts of which a good deal of padi is cultivated, is dominated by the long granite ridge of Kao Sabab on the east, and the three peaks of Kao Sai Dao to the north .Westward a number of low laterite plateaus, fifty feet or so above the surrounding country , form the centre of a considerable population and the pepper-growing district of Ban Kacha . On one of these , overlooking the lower reaches of the river, are the fine remains of the old brick fortress erected by Praya Bodin [1] to check the Cambodians. They are very similar to those at Battambong and Siemrap.’ [p 174 – 5]

At present only joss sticks and small expensive nicknacks are imported from Saigon, the trade with that place being handicapped by the excessive tariffs for which the French colonies are so widely famed, by the high freights charged by the steamers of the Messageries Fluviales which run during high-water season, and by the number of regulations which harass traders going in and out of French territory. It is eloquent proof of the barriers which the French protective policy erects against the commercial success of French colonies that the trade of Battambong should still follow the long overland route to Bangkok in preference to the natural one by water to Pnompen and Saigon, which occupies as many days as the other does weeks. If such is the result of the easy navigation of the great lake, it is permissible to doubt French assertions regarding the success which is to attend the efforts to tap the trade of south-western China, or even of the Lao States, by the toilsome and dangerous Me Kawng. And it is not surprising that the total value of the export and import trade of Battambong and Siemrap does not exceed 80,000 l. a year. If the French colony had not set up the restrictions on trade which have brought about this result, Battambong and Siemrap would long ago have been practically French; and their interests would have been with French Cambodia on the south, instead of with Bangkok. [p 221]

I called on the governor [of Battambang], at his residence inside the old walls which form the Kampeng. He made

it evident that he did not like my way of strolling in unannounced. The Bangkok-Saigon telegraph line passes

through the Muang, and the governor is apparently accustomed to receive telegraphic information regarding

people who propose to do him the honour of visiting his capital. [p 222]

‘Siemrap, like Battambong and Chantabun, was one of the places selected as an outpost against the Cambodians

after the capture of the two lake provinces by the Siamese in 1795. Each town was fortified by a rectangular

Kampeng built of laterite and brick, and with their tall gateways and picturesque touches of red in the midst of

eternal green, they still form imposing memorials to the energy of Praya Bodin, the Siamese officer who erected

them. [p 230]

[Compare with photographer John Thomson’s description from his March 1866 visit: “The old town of Siamrap is in a very ruinous state – the result, as was explained to us, of the last invasion of Cambodia – but the high stone walls which encircle it are still in excellent condition. Outside these fortifications a clear stream flows downwards into the great lake some fifteen miles away, and this stream during the rainy season, contains a navigable channel.” [The Straits of Malacca…]]

‘Another trace of the Siamese garrisons remains in the large number of their descendants who are still found in

the country . Many of the soldiers settled on the soil , and marrying Cambodian women formed little military colonies. Their children’s children still bear unmistakably the likeness of their ancestors, but they have long since adopted the speech of the people round them, and though Siamese is spoken officially, the people all talk Cambodian. The governor, it is to be feared, has not been a very creditable person, but the administration has fortunately for some time been in the hands of the commissioner, Pra Inasa, one of the most pleasant and gentlemanly of Siamese officials. He was appointed for three years to carry out the terms of the Treaty with France of 1893, and he has done it to the letter.’ [p 231 – 2]

[1] Chao Phraya Bodindecha เจ้าพระยาบดินทรเดชา [personal name Sing Sinhaseni สิงห์ สิงหเสนี] (13 Jan. 1776 – 24 June 1849) , a notorious military leader the reign of King Rama III (Rattanakosin Kingdom). Known in Khmer chronicles as Chao Khun Bodin ចៅ ឃុន បឌិន, he fought against the Laotian rebellions, pushed up to Saigon during the Siamese-Vietnamese Wars (1831 – 1834 and 1841 – 1845), and installed Cambodian Prince Ang Em as governor of Battambang in 1834 to resist Vietnamese invasions, which the latter did for four years before switching allegiance.

Fauna and fishermen of the Great Lake (Tale Sap)

The author observed “monitors, otters, the occasional pelicans, crocodiles [in the swampy forest of the margin of the lake, pied kingfisher and the little Indian kingfisher were common, the little black-billed white heron, pond heron, large white heron, grey and purple heron, cormorant’…‘Then, as the waters rise, the [floating] villages are packed up, the boats seek the river mouths, the birds fly inland, and the dirty oily expanse of water does its duty once more as the safety-valve of the Me Kawng [Mekong]’.(pp 225 – 6)

Salt fish exports from the Port of Bangkok: the meticulous tables set by the author show many interesting facts regarding the evolution of overseas trade from Bangkok from 1888 to 1896. In particular, while the volume of shipments of teak wood slowly decreased, the commerce of salt fish – including catches from the Tonle Sap — jumped from 4,286 tons in 1890 up to 2,121,145 tons in 1896.

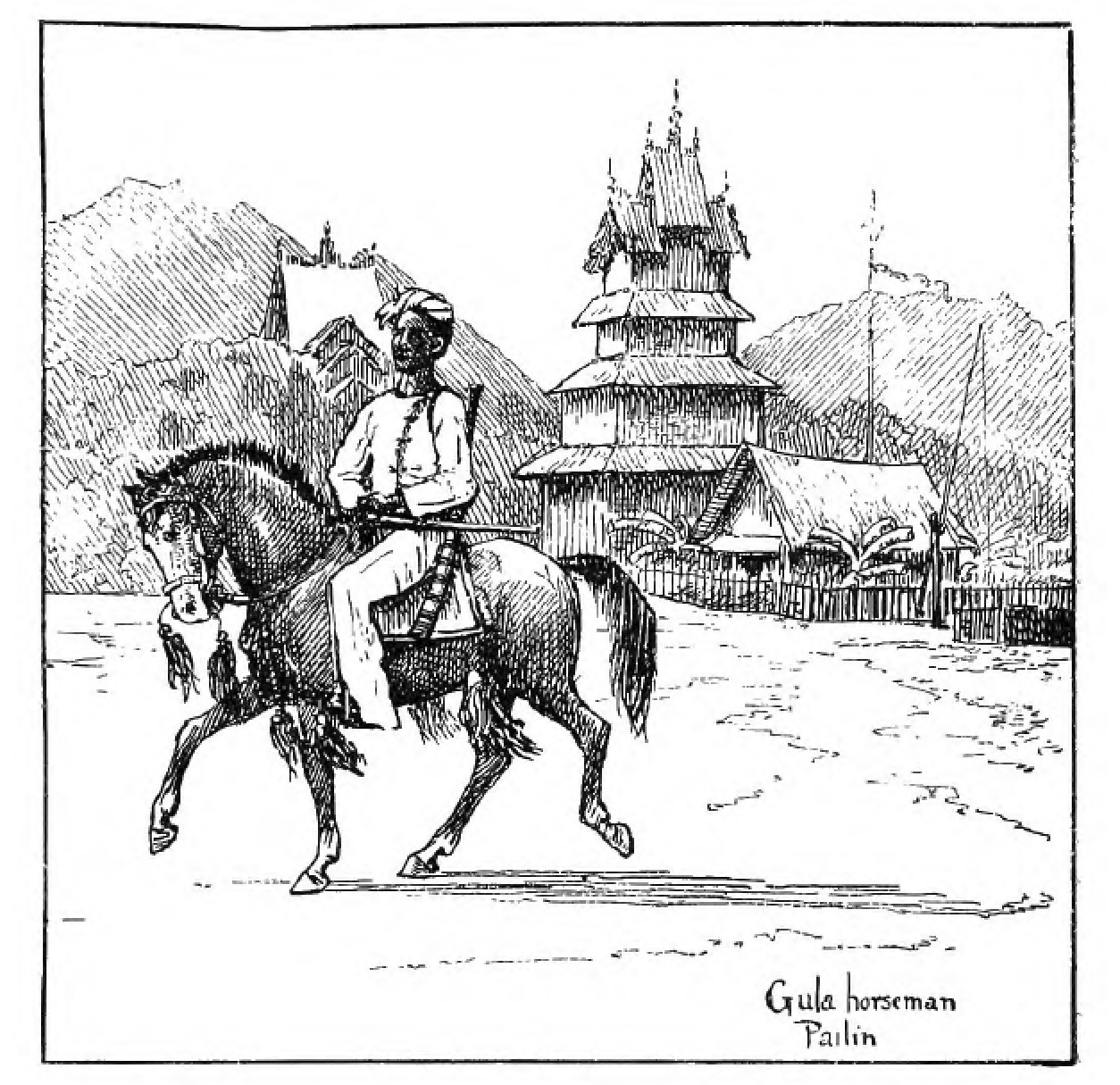

‘Gula’ (Kola) people in Pailin area

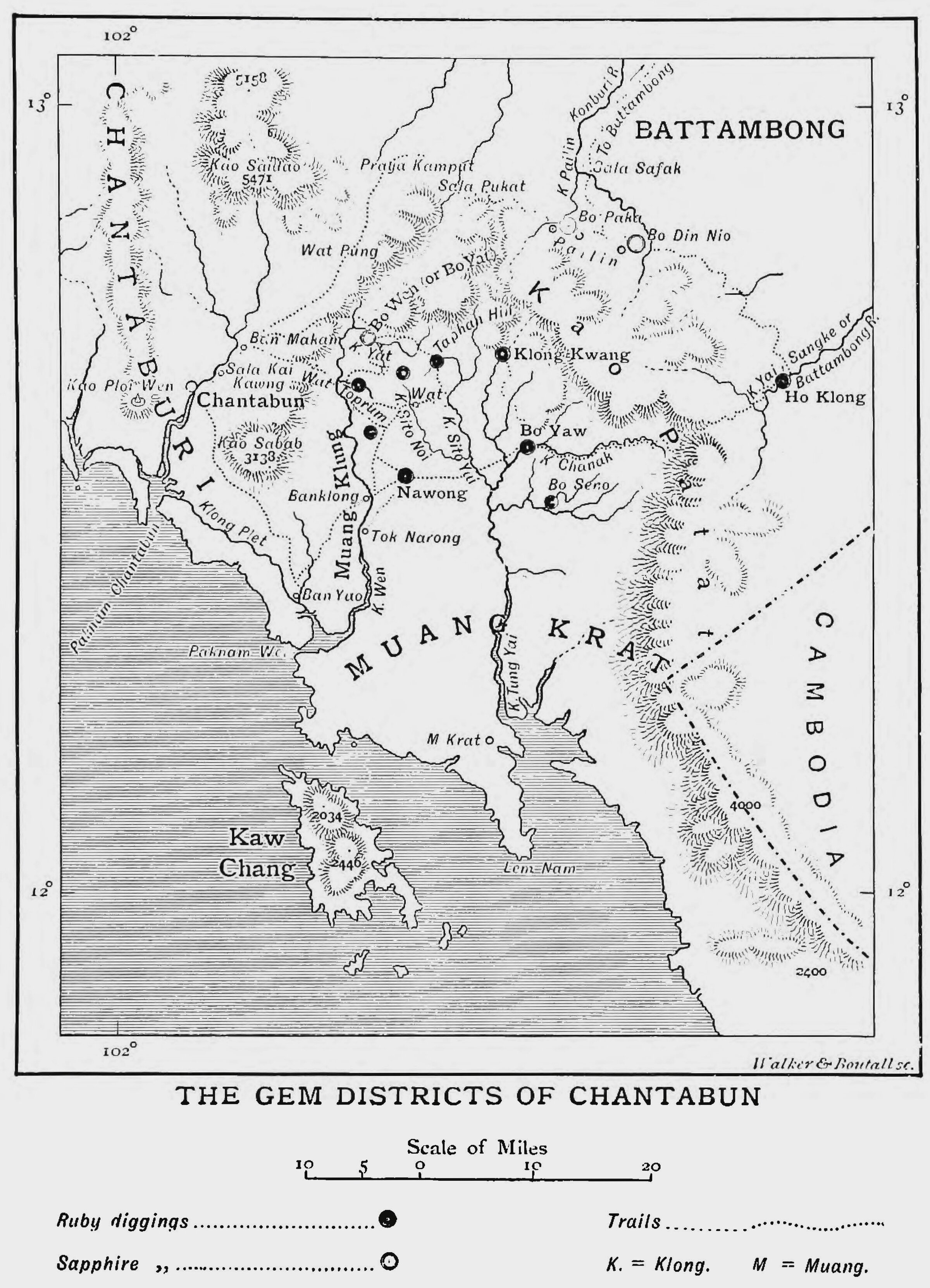

‘Bo Wen was a typical gem diggers’ settlement, and the few houses were inhabited entirely by British Shâns and

a few Lao from about Ubon, who are hired as labourers. The Shâns are practically the only people who stand the climate of the mines for any time. The existence of gems has been known to the Siamese probably for some

centuries, but it was not until the rigid secrecy which the Government had formerly enforced was somewhat relaxed

that an immigration of these indefatigable gem miners commenced, and fresh discoveries began to be reported

every day.

The Shân seems by nature designed for the pursuit of gems. He is bitten with the roving spirit, and in addition

he has the true instinct of the miner, to whom the mineral he lives to pursue possesses a subtle charm, which constrains him never to rest or weary of its search against all odds. The sentiment is quite different to the avarice of the victims of a gold mania. The skill of the Gula is no less than his energy. He detects colour and recognises quality

with a rapidity and accuracy to which few attain. No Siamese, no Lao, no Chinaman can compete with him .

The Burman is about his equal, but has not his industry or constitution, and is therefore chiefly found in the

capacity of middleman, buying and exporting. [p 179 – 80]

The Siamese often style the gem-mining Shâns Tongsu , but there are very few real Tongsus among them. Europeans have usually called them Burmese, but beyond the fact that they come from the Burmese Shân States the term is not applicable to more than an extremely small percentage, and the application of the name to his face

would not be considered flattering by the average Shân. The term Gula, which is most commonly used of the Shâns

in Siam both by the people of the country and by themselves, appears to be in reality the Burmese word Kula,

foreigner.

A Gula (Kola) horseman near the famous Burmese pagoda of Pailin, Cambodia.

The Gula digger is proud and independent. He cherishes the freedom of his life, and he brooks not much official interference. Restraints which may be applied to the African negro will not do for him . When the Borneo Company [Borneo-based, ADB] came to Nawong, diggers were notified (inter alia) that if they worked on the company’s territory they must sell stones to its agents, at prices to be settled by the latter. This was felt to be an infringement of the right to sell in open market, and was resented. Thereafter the company attempted to enforce the right of search on the persons and belongings of the diggers. Rather than submit they left en masse, some for the Pailin mines, others for their homes in Burma. The result was that, out of two thousand eight hundred diggers whom the company found in and about Nawong, a couple of hundred were left when we visited the place; and at Bo Yaw, instead of twelve to fifteen hundred men, there were fifty-four at our visit. Thus the Gula will be seen to be an individual whose susceptibilities must be taken into some consideration. [p 181]

Crossing Klong Kwang, and subsequently Klong Chantung, a rapid flowing mountain tributary, the trail turns more northerly through the dense forest of the foot hills of the Kao Patat, which are now close above to the eastward, Here, as the name of the stream implies, sambur abound, and the tracks of the honey bear are fairly common. As soon as our arrival in the hollow was known in the village, the pu yai , or elders, came out, in the absence of

the headman, and we were given the use of a wing of the house of one Mong Chong Yüe, whose decidedly charming and pretty Shân wife did all she could to make us comfortable. We had to submit to the good-natured

scrutiny of a jovial crowd of diggers, to whom the mechanism of our guns was a source of much joy. [p 192]

The Pailin diggings are divided into two districts, Bo Yaka, which has been regarded as the headquarters, and

Bo Din Nio, which lies nearly five miles south and is the more populous of the two. They are connected by a good road, equipped with bridges and comfortable salas at intervals. Order and neatness reign supreme, and comfort and a certain luxury are apparent in all the villages. Here, from the squalor of south-east Indo-China, one is transported to the smartness of a village in Upper Burma. The bells on the gables of the many-roofed Pungyi Kyoung, or on the high angel-guarded masts, tinkle in the strong easterly wind; the little gongs in the building ring at intervals through the day and night; the tall pagoda on the hill above looks down on the palm-fringed street, where pink ‘passohs’ and broad Shân hats glance in the sun, and pretty Shân maidens wear roses in their hair. […]

Wherever the sinking to be done exceeds a few feet, the Gula of Pailin likes to have it done for him by Ubon and Bassac Lao, like our friends at Bo Wen, who are employed in considerable numbers. North and eastward down the valley work was not going on so actively, but the view behind was very typical-the short strong-limbed Lao working hard, the gay Gulas, in their gaudy passohs, squatting and smoking over their pits, the long-armed bamboo lifts working as busily as semaphores, and the dark-green jungle and straight white stems towering up above it all. There was little sound but the creaking of the lifts and the hammering of the busy little coppersmith in the tall forest trees. It is curious that no stones have been found beyond Klong Noi, the stream on the left bank of which Bo Din Nio stands, although they have been worked right up to the left bank; and the limit to the north appears to be a granite dyke which cuts in through the quartzite at the ford at the lower end of the Klong Kawan district. [p 202, 205 – 6]

‘Chart of the Gems Districts of Chantabun’, by H. Warington Smyth, ca. 1896. [source: Travels in Siam, vol. II, p. 179]

‘Chart of the Gems Districts of Chantabun’, by J. Warington Smyth, ca. 1896. To our knowledge, the most exhaustive map of sapphire and rubies mines in activity at the end of the 19th century.

CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME

- XV. THE MALAY PENINSULA (continued) WEST COAST West Coast Provinces : Paklao, Gerbi , Trang, Pang Nga, Takuapa [Kopa], Renawng. p 1

- XVI THE MALAY PENINSULA (continued) EAST COAST Petchaburi to Champawn-Old trade routes. p. 34.

- XVII. THE MALAY PENINSULA. EAST COAST (continued) Champawn to Langsuan and Chaiya. p 57.

- XVIII. THE MALAY PENINSULA. EAST COAST (ctd) Chaiya to Sungkla (Singora) ‑The Tale Sap & Patalung. p. 82.

- XIX. THE MALAY PENINSULA . EAST COAST (continued) Sungkla to Lakawn. p. 122.

- XX. THE CAMBODIAN PENINSULA The Coast-Bangplasoi to Chantabun and Krat. p 141.

- XXI. THE CAMBODIAN PENINSULA (ctd) Chantabun : The French occupation — Gem districts in M. Klung and M. Krat — Shān diggers. p. 169.

- XXII. THE CAMBODIAN PENINSULA (ctd) Battambong : Gem districts ‘Prattabong ’ — The Tale Sap- Siemrap ‑Nakawn Wat and the Ruins. p. 198.

- XXIII. SIAM IN 1896 – 7. Recent Siamese Legislation. p. 240.

- APPENDICES. pp. 261 – 319.

I. TIDES AND WINDS ON THE MENAM | II. SHIPPING AND TRADE OF BANGKOK | III. DETAILS OF RICE EXPORT | IV. DETAILS OF TEAK EXPORT | V. ESTIMATE OF REVENUE | VI. DETAILS OF CATTLE EXPORT | VII. TRADE IN THE LAO STATES | VIII. THE KEN AND LAO REED INSTRUMENTS | IX. MERGUI PEARL FISHERY | X. TIN PRODUCTION OF PUKET | XI. ITEMS OF REVENUE OF TRANG AND PALEAN | XII. EXPORTS OF WEST COAST PROVINCES | XIII. DETAILS OF PEPPER EXPORT | XIV. SIAMESE NAMES FOR THE WINDS | XV. SOME AIRS OF SIAM | XVI. BIRDS | XVII. SOME FEATURES COMMON TO SIAMESE AND ANCIENT CRAFT. - GLOSSARY

- LIST OF AUTHORITIES

- INDEX

Tags: Siam, Khmer influences, architecture, geography, geology, mining, Mekong River, gold, gems, Indian influences, Mon-Khmer, Malay Peninsula, trade, Krat, Tonle Sap Lake, mines, Cambodia-Siam, fishing, fisheries, Burmese emigration, Kola, Battambang, Siem Reap, Malaysia

Associated Items

Booksby Herbert Warington Smyth

Booksby Herbert Warington Smyth

About the Author

Herbert Warington Smyth

Herbert Warington Smyth, “Warington” (4 June 1867 – 19 Dec. 1943, Redruth, UK) was a British traveler, writer, naval officer and mining engineer who served the government of Siam in the 1890s and later held several posts in the Union of South Africa.

Warington went to Siam in 1890 as an unpaid assistant to the Mineral Adviser to the Office of Woods, was Secretary of the Government Department of Mines from 1891 to 1895, and Director General from 1895 to 1897. He was secretary of the Siamese legation from 1898 to 1901.

In his book Five Years in Siam, and especially in his study Exploring for Gemstones on the Upper Mekong — Northern Siam and Parts of Laos in the Years 1892 – 1893 (repub. by White Lotus, Bangkok, 109 p., ISBN 9748434249), he accounted his six-month journey from Bangkok to Luang Prabang and through Nong Khai and Korat, exploring the regions opposite Chiang Khong, on the left bank of the Mekong, for deposits of rubies and sapphires.

Warington had a special interest in the Tonle Sap (which he called “Tale Sap”) for geological and hydrological reasons, and he visited the Siem Reap-Battambang area while “being busy making expeditions in various directions in pursuit of rumoured gold mines”, as he noted.

A dedicated yachtman, he also published in 1906 Mast and Sail in Europe and Asia, and in 1925 Sea-wake and Jungle Trail. He also observed the boat races in Bangkok, noting that the crews were often made of men and women, and the latter, “with their cross sashes of yellow, green or blue, not only looked but also proved the smartest”. He himself illustrated most of his published book with sketches, drawings and maps.