Tantra, Magic and Vernacular Religion in Monsoon Asia (Introduction)

by Andrea Acri & Paolo E. Rosati

Preface to a collection of documented essays on Tantrism, particularly in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

- Publisher

- from Tantra, Magic, and Vernacular Religions in Monsoon Asia: Texts, Practices, and Practitioners from the Margins, Routledge, London.

- Published

- 2022

- Author

- Andrea Acri

- Pages

- 230

- ISBN

- 9781003281740

- DOI

- https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003281740

- Language

- English

pdf 1.8 MB

But first, what do we call ‘tantra’, exactly? While the preface writers and editors of this high-level collection of essays do not feel the need for going back to the Sanskrit etymology of the word, this platform is aimed at laypeople, too, and so: Tantra, तन्त्र, originally means ‘loom, weave, warp’, evolving to design an esoteric tradition in Hinduism and Buddhism, yet keeping the meaning of “text, theory, system, method, technique, practice’ in the Indian continent. In the post-modern, countercultural context, the term came to encompass many eclectic spiritual and physical experimentations.

As the editors remark in their introduction, “Tantra (used here as a synonym of ‘Tantrism’) is a complex, heterogeneous, and protean socio-religious phenomenon. The very definition of Tantra and its status as a clearly identifiable discourse, in spite of the existence of such emic [emic meaning from an internal (native) point of view. ADB] terms as tantra and tāntrika, is a matter of controversy. Some scholars would restrict Tantra to texts and artefacts associated with initiation lineages within specific (and as a norm, esoteric) soteriological systems across sectarian domains of Indic religions; others, applying a broader perspective, would understand the phenomenon as transcending the boundaries of the belief systems and rituals produced within textually and historically established initiatory traditions so as to encompass multifarious manifestations of the cultural, artistic, and political lives of many societies of the wider Indic or ‘Indianized’ World.”

Monsoon Asia

“While the enigmatic origins of Tantra are still debated, textual and art historical evidence suggests that Tantric traditions identifiable as such arose in the Indian subcontinent from the middle of the 1st millennium CE. From ca. the 7th to the 13th century and beyond, Tantric orientations of major religious traditions of ‘Hinduism’ (especially Śaivism and Śāktism) and Buddhism (especially the Sanskrit- dominated Mahāyāna current, but also the Pali-dominated tradition that became a major force in mainland Southeast Asia from the 12th century onwards) virtually coincided with mainstream religiosity and ritual practiceover much of Asia. Transcending the constructed boundaries of the region we now call ‘South Asia’, Tantra spread over the large swathe of territory referred to as Monsoon Asia and continues to this very day to play a central role in the religious and ritual life of many ‘peripheral’ areas of the former Indic World, such as Nepal, Tibet, and Bali.”

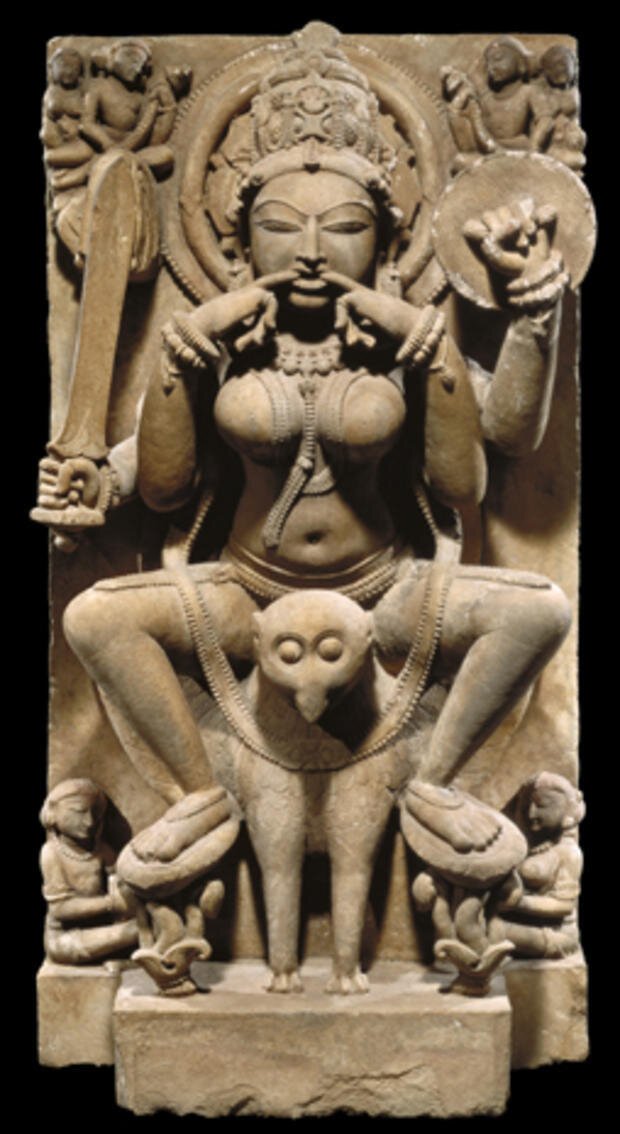

Statue of a yogini, Kannauj Temple, Uttar Pradesh, India (San Antonio Museum/Smithsonian Institute)

“Tantric Theravada”

“Taking on a local garb according to the sociocultural and geographical contexts in which it developed, Tantra has played a significant role — albeit often in a subliminal manner — in shaping the sharedhistory and collective identity of a geographically vast and culturally diversified region encompassing the continental and maritime space of the southeastern quadrant of Asia. To give an idea of the cross- cultural potential of the application of a broader definition of ‘Tantra’ to disparate socio- cultural contexts across place and time, we may cite the list of seven features individuated by Crosby (on the basis of earlier studies by François Bizot) to define the Pali- dominated Buddhist tradition of modern Thailand and Myanmar as ‘Tantric Theravāda’— namely,

(1) ritual creation of a Buddha within one’s own body;

(2) the use of sacred language for the identification of microcosm and macrocosm;

(3) sacred language as the creative principle (or the arising of the Dhamma from the Pali syllabary);

(4) a system of analogic substitution/homologization;

(5) ‘[e]soteric interpretations of words, objects and myths that otherwise have a standard exoteric meaning or purpose in Theravāda Buddhism’;

(6) necessity of initiation; and

(7) the application of the six previously outlined methods to pursue mundane and supramundane goals”.”

Weretigers

“The final chapter, ‘Tantrism and the Weretiger Lore of Burma, Thailand, and Cambodia’ by Francesco Brighenti explores traditional beliefs about weretigers as physical shapeshifters found among, on the one hand, Austroasiatic-speaking tribal groups inhabiting the Shan Plateau, the Upper Laotian highlands, and the Annamite Cordillera, as well as Tibeto-Burman-speaking ethnic groups of northern Myanmar, and, on the other, the Theravāda Buddhist societies settled in the river valleys and alluvial plains of Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia, where similar weretiger beliefs form a little- studied aspect of the prevalent magical lore. Noting that oral traditions regarding human-to-tiger transformation in the last three countries have clear links with Tantric black magic, possibly as a result of the early prevalence of Mahāyāna- cum- Tantric Buddhism (and, as far as the Khmer Empire is concerned, of Tantric Śaivism too) in those countries during the mediaeval period, and their later continuation as ‘Tantric Theravāda’ complexes, Brighenti assesses the interplay of indigenous (Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, Tai) and South Asia-derived (Tantric) cultural traditions that shaped the weretiger lore of lowland mainland Southeast Asian societies.”

Tags: tantra, tantrism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Theravada Buddhism, esoterism, magic, fertility rituals, spirits, chamanism, religion, sociocultural essays, reference documents, Indianization, sexuality, death, Saivism, Shaktism

About the Editor

Andrea Acri

An Assistant Professor in Tantric Studies at Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE) and PSL University in Paris, Andrea Acri (b. 1981) is a researcher in Hinduist and Southeast Asian religions and languages.

With a Laurea degree in Oriental Cultures and Language from Sapienza University in Rome, he specializes in Sanskrit scriptures and their translations to Southeast Asian languages, in particular Old Javanese and Old Balinese. His publications include the monograph Dharma Pātañjala (2011), as well as various edited volumes, including Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia (2016). His main research and teaching interests are Śaiva and Buddhist Tantric traditions, Indian philosophy, Yoga studies, Sanskrit and Old Javanese philology, and the comparative religious history of South and Southeast Asia from the premodern to the contemporary period, with special emphasis on connected histories and intra-Asian maritime transfers.

About the Editor

Paolo E. Rosati

With a PhD in Asian and African Studies (2017) from Sapienza University, Roma, Italy, Paolo E. Rosati has published a double special issue on Tantra for Religions of South Asia (14/1 – 2) in 2020, and several contributions on the yoni cult at Kāmākhyā (Assam, India), the temple devoted to the Shakta Tantric deity considered as the goddess of desire.

His current research focuses on magic, memory, and cultural identity in postcolonial Tantric contexts, post-structuralism, post-modernism, deconstruction, and post-genderism as a research approach.