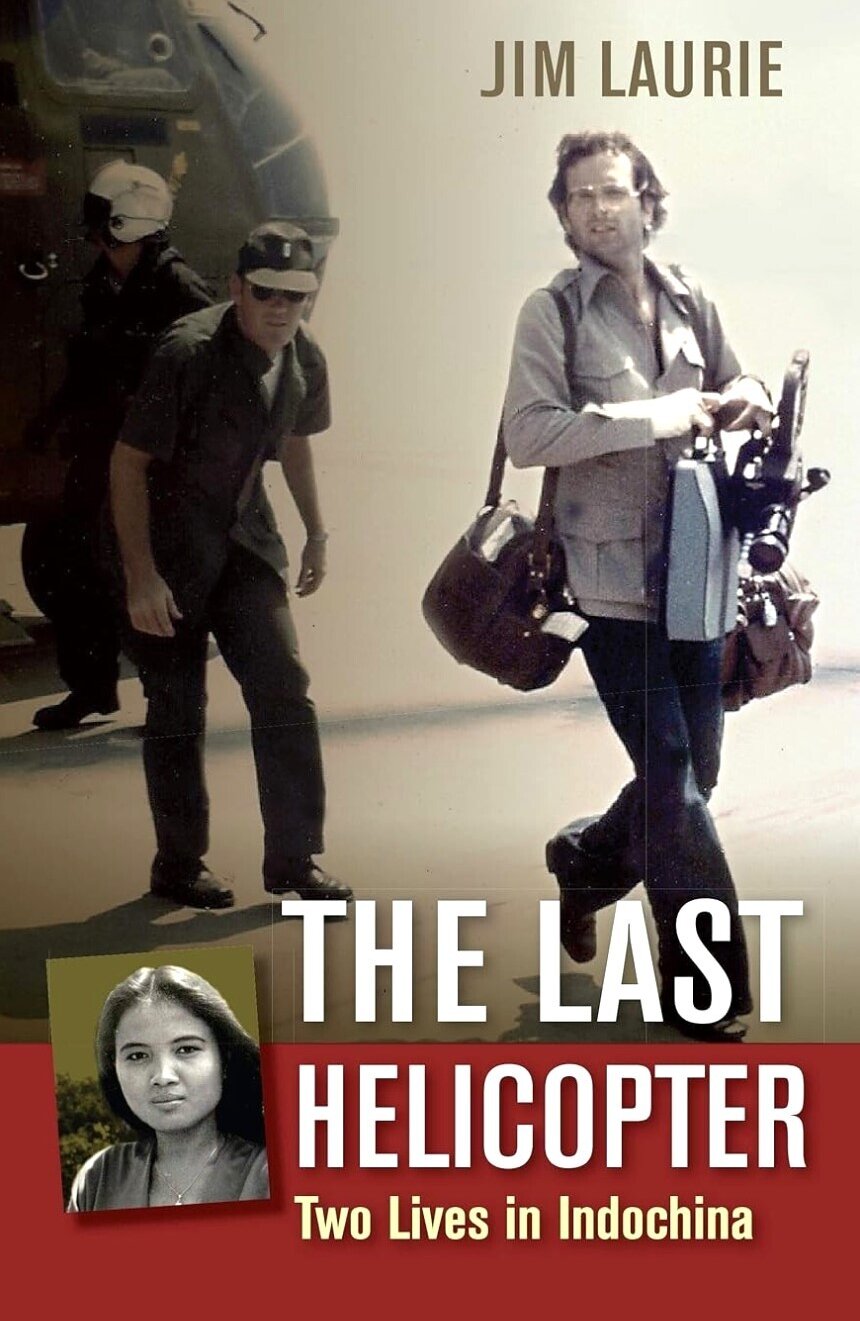

The Last Helicopter: Two Lives in Indochina

A poignant and lucid love story set in war-torn Cambodia, by a former war TV correspondent who covered Southeast Asia's most tragic years.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- self-published

- Edition

- Kindle

- Published

- 2020

- Pages

- 366

- ISBN

- 978-1735120300

- Language

- English

Writing about a love story during wartime is a perilous exercise for a war correspondent [disclaimer: the author of this review, Bernard Cohen, himself covered several armed conflicts worldwide in the 1980s and 1990s] — unconsciously, you tend to embellish memories, including your own bravery, and to downplay your real feelings as just a part of heightened emotions triggered by danger. That is why the author’s account is remarkably clear-eyed, acknowledging his emotional flaws, his difficulties to understand the innermost motivations of the beloved one due to their cultural differences, and at the end leaving us with a truly beautiful portrait of a Cambodian woman torn between her love for her country and her aspiration to freedom.

Between 18 June 1970, when a 22-year old American rookie journalist met at a war briefing in Phnom Penh the young and striking Sinan, a Cambodian working for several NGOs, and 29 January 2011, when he “brought an old friend home again” — the remains of Sinan, who had departed Cambodia in January 1980 for the US, and had died late 2010 in Washington DC, ashes that he dispersed in the Mekong River along with her oldest friends –, this remarkable book develops as a gripping love story while giving us a precious account of what was life before, during and after the Khmer Rouge.

Rather uncommon for your typical war correspondent is the perception of cultural traits of daily life. Discovering Phnom Penh in 1970, he “found it an extraordinary city. It had a tranquility and charm that I had not yet found in Asia. It had none of the modernity or sophistication of Tokyo, none of the hustle of Hong Kong, and so far none of the war-weariness of Saigon. One evening, when Sinan excused herself, explaining that she had an office event to attend, I headed off to one of the floating dance clubs along the Bassac River. I crossed a slightly wobbly gangway onto a large barge berthed on the river. The lights were turned low, a sprinkling of glittering colored bulbs decorating the edges of the room. I watched, mesmerized, as a hundred or so Khmer held hands and swayed in a well-choreographed line dance. The display became what the Khmer call the “romvong.” Slowly moving in a circle, young men and women stretched out their hands and arms. They seemed to be attempting some of the graceful moves I had seen among dancers of the Royal Ballet. What struck me was the seeming innocence of the occasion. These were people my age or younger, so far untouched by war, displaying a carefree life that was destined to soon change. The contrast with what I had seen in Saigon in my first months there could not have been more dramatic. South Vietnamese in their capital partied too. But young Vietnamese adopted the music and dance of the Americans. Energy and tension combined to provide young Vietnamese a mood of watchful waiting: waiting for war to touch their lives.”

To quote the preface, “this is a story of lives and contrasting cultures that intersect in remarkable and unexpected ways; a story of youth, a thirst for education, travel, romance… and love — not only for a individual but for an endlessly fascinating place — a region encompassing Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos — known collectively as Indochina. The story focuses on a special friend, an extraordinary person at an extraordinary time. A young woman is engaged in a remarkable struggle for survival amid unimaginable conditions. Along the way she unveils a chronicle of war and recovery, trust and betrayal, lessons learned and lessons forgotten. This is a story of lives interconnected. A story connecting people bound together for a time, by war, pain, and the inability to forget.”

And always in the background, Angkor, this symbol of Cambodianess that young Sinan had visited as a child and where the young lovers planned to go in July 1971: “We talked about flying to Siem Reap. Was it too late to see Angkor? I felt nervous. Although it was very early in the war, security had already deteriorated around the temples. But Sinan wanted to return. “Let’s plan it then. Let’s go,” I told her. What could be more romantic? I would take a long weekend and go off among the temples I had only read about. I’d watch the sunset over Angkor Wat and wake up the next morning next to a beautiful Khmer woman. Malraux, eat your heart out! I made inquiries of Royal Air Cambodge and asked whether I could afford the finest room either at the Auberge des Temples or at the Grand Hotel D’Angkor. I wanted to make it special, to provide Sinan a different experience at Angkor. She had been there as a child. Sinan traveled there in April 1959 with her oldest sister Sithan and her brother-in-law. Although she was only 11, Sinan remembered the journey vividly, speaking excitedly of a visit she wanted to repeat […] Sinan described her favorites. Beyond Angkor Wat stood the temple of Ta Prom. As the tourist brochure proclaimed, Ta Prom featured “impossibly intricate stonework seemingly throttled by gnarled, thick trunked Banyan trees.” Sinan’s only disappointment, she said, lay in not being able to travel 15 miles further north to the low hills of the Phnom Kulen and the splendid, intricately carved temple of Banteay Srei. That’s where La Voie royale’s Malraux had stolen his statues. Sinan explained that even in 1959, security in the region north of Angkor could not be guaranteed. Less than six years after independence, rebellion was brewing against the rule of Sihanouk. Small rebel groups formed; many Cambodians believed financed by the Americans. Sinan repeated that opinion. “I could not go to Bantei Srei,” she said, “because the opponents of Sihanouk were there and funded by the ‘SAY, Eee, AH’” (the Khmer pronunciation of “CIA”). “The Americans wanted to drag us into the war in Vietnam, even back then. I’m sure of it.” So it was that suspicions of American interference were planted in the Cambodian mind not long after the French colonials departed the region. American interference and betrayal, as well as kindness, would influence Sinan for the rest of her life.”

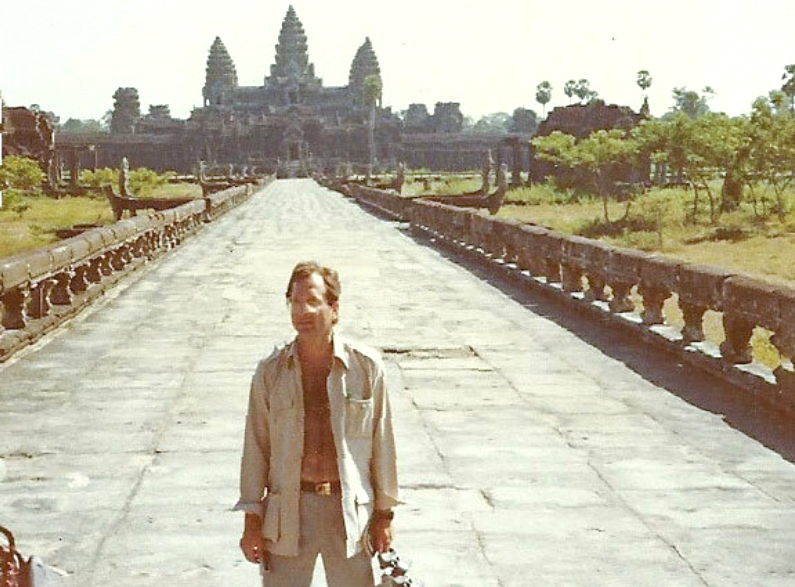

It was only in November 1979 that the author finally saw the Angkor temples: “A pleasant excursion walking through the abandoned temples of Angkor in a small way lifted my spirits. As I walked around the complex, with Vietnamese troops providing security, my mind wandered back to 1970 when Sinan and I planned our visit to Angkor before war intervened. It would have been so much better if Sinan and I had been there together[…] Apart from Vietnamese troops and a few Khmer civilians trying to recover from the impact of the Khmer Rouge régime, the Angkor Temples were abandoned. Large parts of the complex were inaccessible due to landmines.”

Watch some images by Jim Laurie while reporting from Phnom Penh in April 1975.

Tags: 1960s, 1970s, Modern Cambodia, daily life, wars, Vietnam War, Khmer Rouge