The Bogus "Radcliffe Collection" and its Magnificent Pieces

by Andy Brouwer

Elucidating the mystery of a bogus collection by the late master trafficker Douglas Latchford. Some of the pieces are now back to Cambodia.

- Published

- October 19th, 2024

- Author

- Andy Brouwer

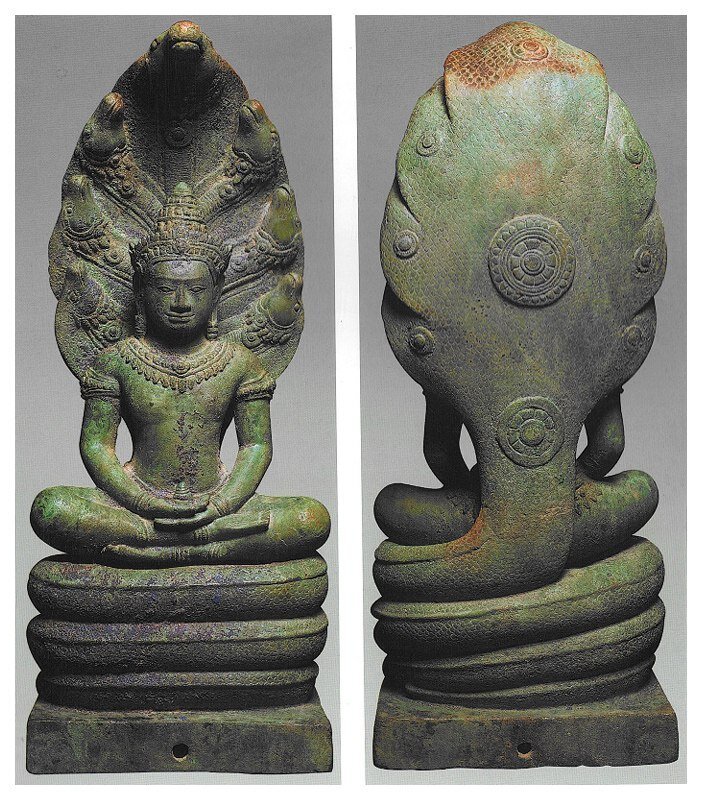

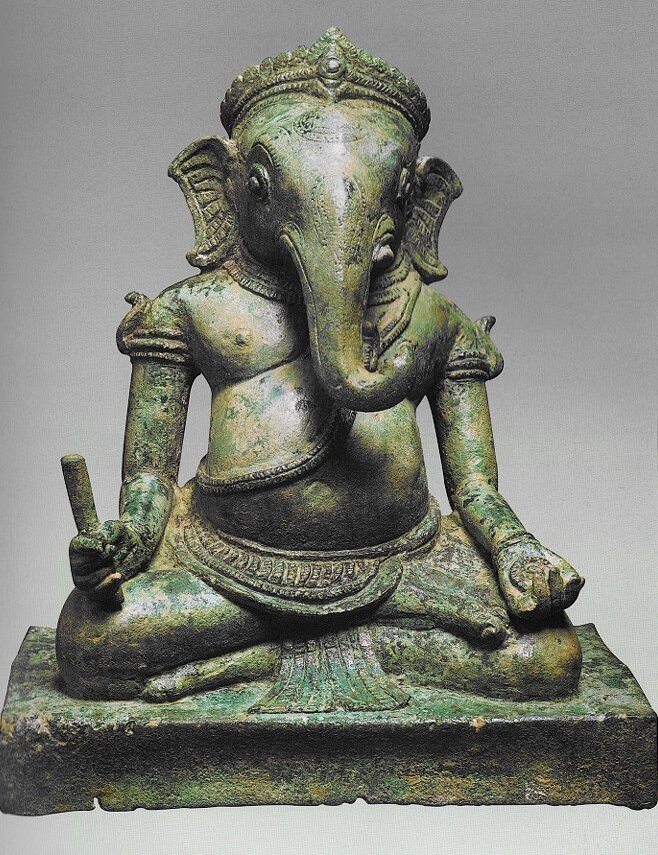

Whilst delving into the history or provenance of recently returned Khmer antiquities, the three glossily-produced catalogues of Khmer art published by Douglas Latchford [Douglas Arthur Joseph “Dynamite” Latchford (15 Oct 1931, Bombay (Mumbai), India – 2 Aug 2020, Bangkok, Thailand)] and co-author Emma Bunker, loom ever large. In particular, their first book, Adoration and Glory: The Golden Age of Khmer Art [“AG” in our captions], with over 500 pages awash with spectacular Khmer antiquities and descriptions, remains an invaluable reference source.

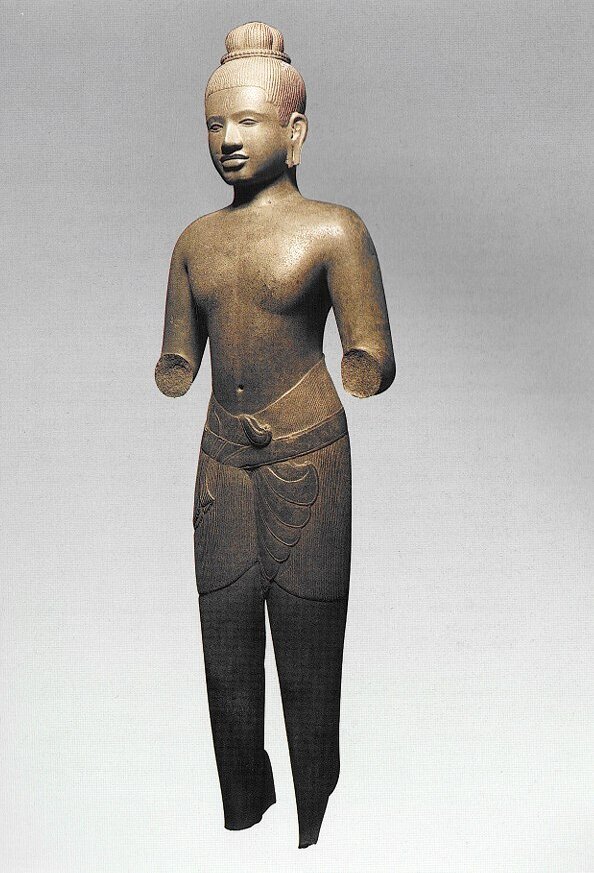

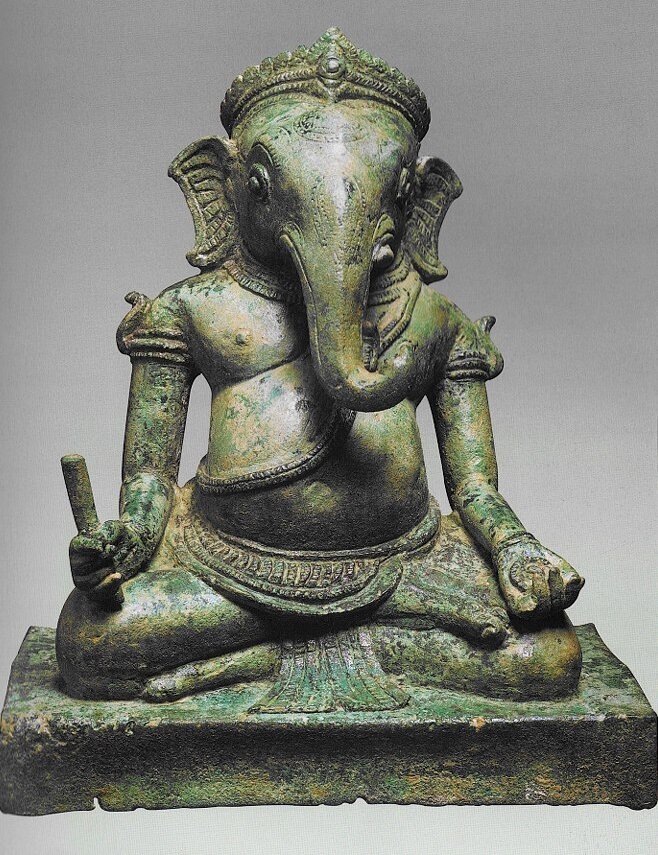

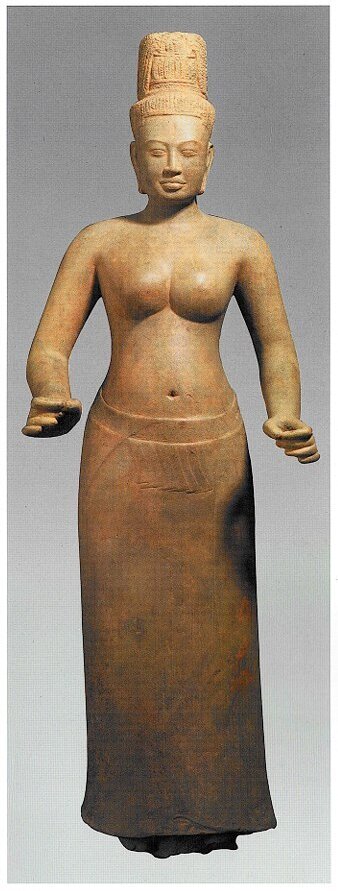

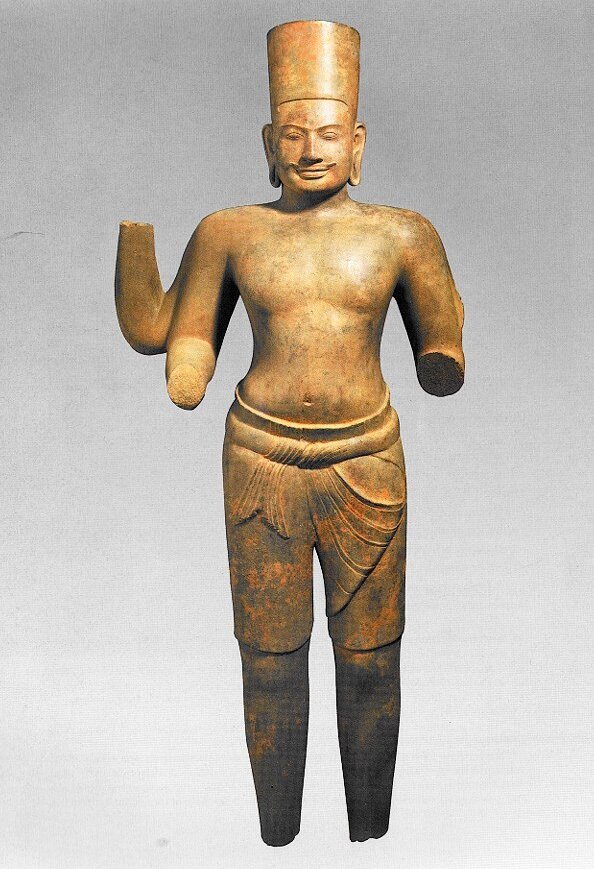

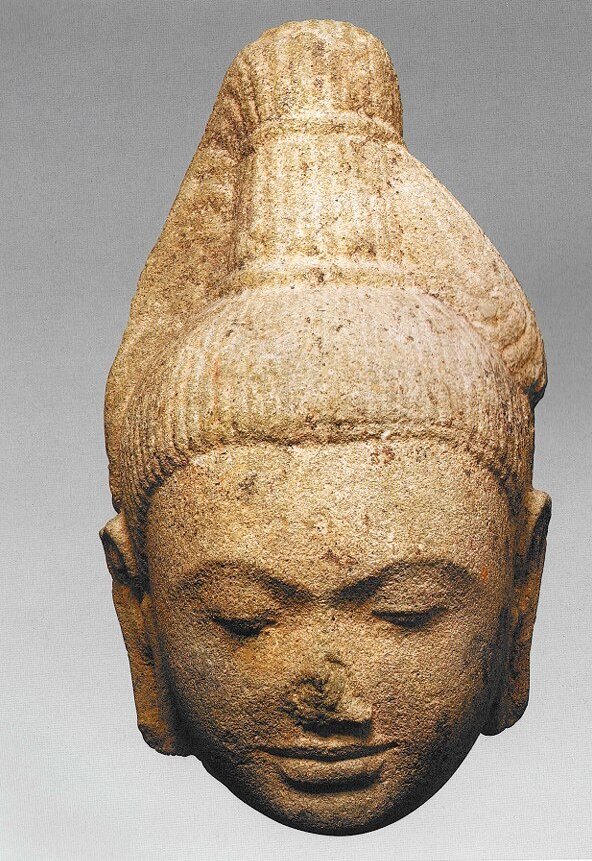

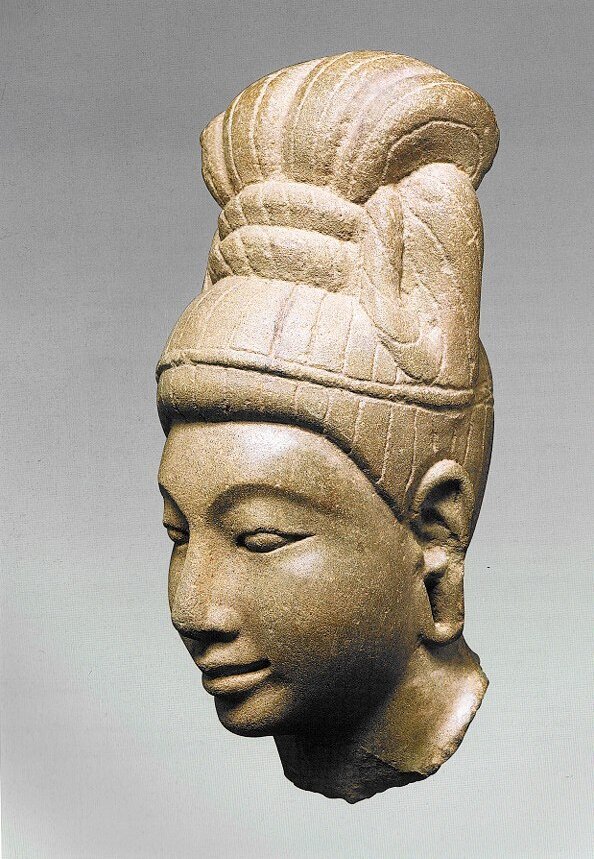

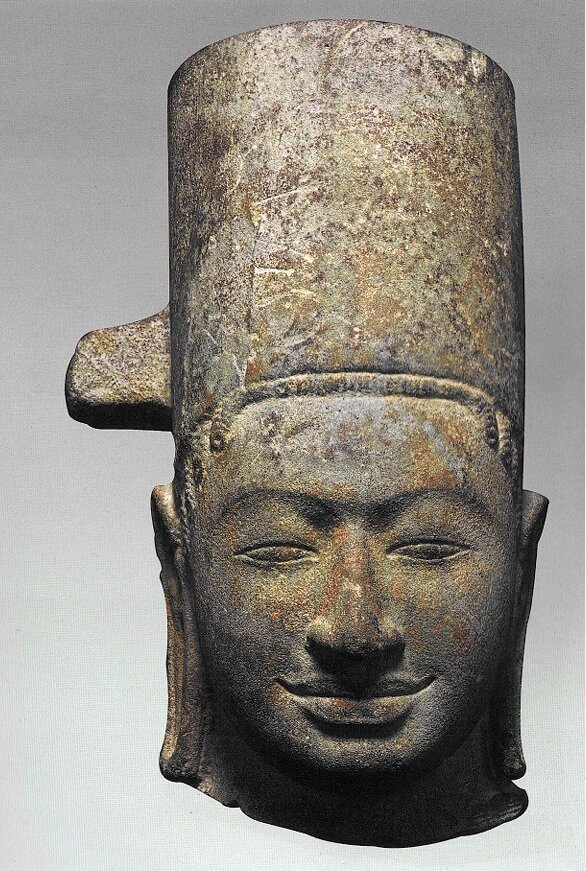

However, in the twenty years since the book came out in 2004, our knowledge of the world of Khmer artifacts has undergone a dramatic change. The names of Latchford and Bunker are no longer held in the high esteem they once were, in fact, the exact opposite is now true. As an example, 19 artworks in Adoration and Glory were credited to the “Radcliffe Collection,” presumed at the time to be a private collection of Khmer antiques of exceptional quality. No-one could trace who owned the Radcliffe Collection until the authors explained that the name was conjured up so the owner could remain anonymous. It transpired that that owner was none other than Douglas Latchford himself, who secretly operated his own trafficking network from his headquarters in Bangkok, sending looted Khmer treasures around the globe for nigh on five decades.

Those 19 artworks were in Latchford’s own personal collection at the time of the book’s publication, though some would later be sold to wealthy private collectors like James H Clark. He even mistakenly credited two pieces, a Prajnaparamita and a Maitreya, in both the 2004 book and in his 2011 book on Khmer Bronzes, to two separate collections, the latter being Skanda Trust, which was another fabricated collection, of some eighty bronze items, all owned by Latchford. Here are the 19 Radcliffe images from Adoration and Glory, with an update on their whereabouts, where known. I’m hoping more of them will be returned by the Latchford family in the very near future, as a number of them were photographed in the London apartment of Latchford in 2014.

To give a window into how the 2004 book Adoration and Glory was received in Cambodia upon its publication, we quote here the article journalist Michelle Vachon dedicated to it at the time [“In Pursuit of Provenance”, The Cambodia Daily, 29 May 2004]:

From the very first pages of their recently published book “Adoration and Glory, The Golden Age of Khmer Art,” (2004) authors Emma Bunker and Douglas Latchford challenge those who may venture to criticize their approach. That approach has been to use private collections of Khmer artifacts without provenance and background history that establishes authenticity to present “a celebration of the artistic achievements of the Khmer”. Defending their celebration of Khmer artwork acquired privately and, until now, never shown publicly, Bunker and Latchford argue in their preface that it would be “irresponsible” to dispute a sculpture whose origins cannot be traced, have not been revealed, or that do not have typical Khmer characteristics. “If an artifact without provenance can be provided with a cultural context through scholarly research, how much better to publish than to ignore it,” Bunker and Latchford wrote in the preface.

But the authors have gambled, critics claim, on presenting Khmer art pieces with no history, or maybe a history that is better not told. The pieces are not only featured in their book, but also given a cultural context from which they are meant to have come. This was done, not by telling exactly where and how the artworks were obtained which would help to prove their authenticity but by comparing them to genuine Khmer pieces currently in museums. For Khmer art experts, the main concern with this approach is not whether these art works were purchased legally Cambodia has been battling illegal artifact smuggling for years but that many of the art works featured in this new book may not be genuine.

Of the 180 Khmer pieces featured in “Adoration and Glory”, a glossy 495-page, large-format, color reproductions book, 115 items were contributed from private collections whose owners wished to remain nameless. Seventeen [actually it’s 19] of the artifacts were from the so-called Radcliffe collection, a name the actual owner conjured up to remain anonymous, the authors explained. And among the art pieces featured from museum collections in the US and Cambodia, eight were on loan from the collections of anonymous owners. Most of the pieces are given at least a two-page spread, one full-page photograph and one page of explanatory history. “There are many reasons for lack of provenance, and to ignore pieces without provenance denies the world the information they can provide. Collectors, both public and private, are custodians of someone else’s culture and have an obligation to share the fruits of that culture with the world,” the authors wrote. As they mention, since the nineteenth century when Angkor Wat first achieved international acclaim, “the passion for Khmer sculpture fueled a universal desire to collect it.” But as art experts point out, there is a danger in featuring artifacts of unknown provenance in a well-researched book, as private-collection pieces without a proven history gain an air of authenticity and antiquity dealers never fail to show prospective buyers books in which artifacts are featured.

It sometimes takes the eye of a person who has seen thousands of Khmer sculptures to tell a genuine piece from a fake, said Khun Samen, director of the National Museum. And “beautiful forgeries” have found homes in museums around the world, he said. Some characteristics do not lie, Khun Samen said, noting by way of example, that the face of a Buddha sculpted by a Chinese or Thai artist will be different from one chiseled by a Cambodian. “In addition, there are some facial features [in genuine Khmer sculptures], a smile expressing sensuality and a profound serenity that modern artists don’t understand,” Khun Samen said.

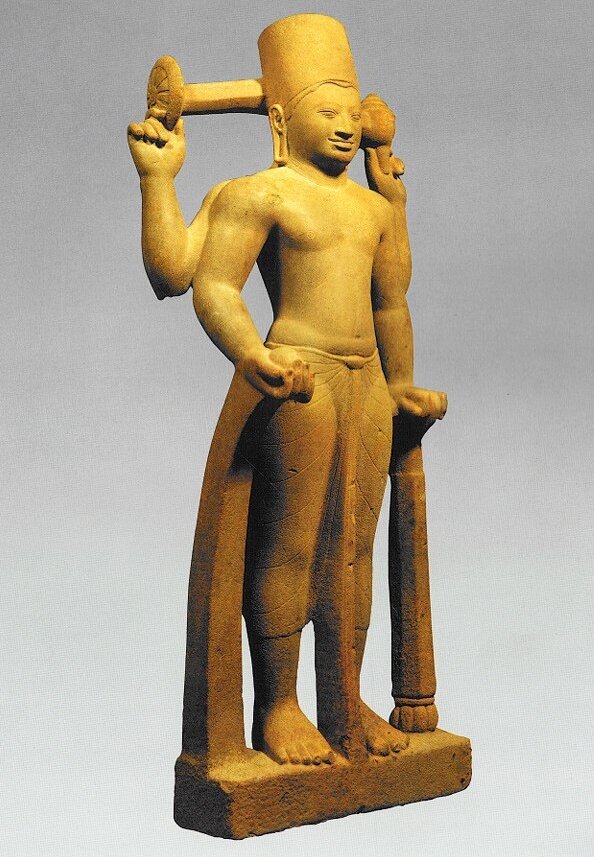

Bertrand Porte, who is in charge of the restoration workshop at the National Museum of Cambodia, described the book as a golden opportunity of studying, in one publication, fake Khmer sculptures whose existence experts suspected but never found proof of. Porte said he plans to write a paper on Khmer-art forgeries he has come across over the years, and dozens in Bunker and Latchford’s book like the sandstone sculpture of a Hindu deity Vishnu featured in the book, which Porte said adamantly was a forgery are similar in style to other forgeries. The fake artifacts are so similar as to almost constitute separate “schools of fakes.” Many other pieces also left Porte and other Khmer-art experts with questions, but they said that time with the actual artworks was necessary before making decisions.

The Guimet Museum in Paris, which has the largest Khmer-art collection in the word outside the National Museum in Phnom Penh, also intends to publish a report on Bunker and Latchford’s book in one of its scientific publications, said Pierre Baptiste, Southeast Asia curator for the museum. The aim is to assist specialists to differentiate the genuine Khmer art pieces in the new book from the forgeries, said Baptiste, adding that the book contains some major pieces that have never been seen before or documented. “This book is dangerous in the way it combines the worst and the best,” said Baptiste. “While stressing the considerable work that this book has entailed, we want to believe that, in fact, it is a testimony of a love for Khmer art that is free of mercantile considerations, and that possible mistakes are due to the excessive optimism that sometimes characterizes our American friends,” he said.

Bunker said in an e‑mail that she was surprised by the number of Khmer artworks in museums that have not been researched or reported on, in part because British and US scholars tend to have concentrated more on Indian art than on Southeast Asian artifacts. “Most publications of Khmer art up to the present have dealt primarily with the same works of art that have been discussed over and over again for years, so it seemed exciting to bring some new material into focus,” she said. “We have known many of the private collectors for years, and had a wonderful time researching their pieces, many of which have been hidden away for decades.” Bunker also said that she had spent a great deal of time comparing the pieces published in her book with other artworks published in earlier Khmer art books.

However, Porte wondered how some of the major artifacts, identified in the book as having been found in Cambodia, could have ever escaped notice in their home of origin if they were, in fact, genuine. For example, the Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient (EFEO) has taken thousands of photos and done massive documentation of Khmer art; this French government agency has been studying, cataloguing and restoring Khmer art and architecture for more than a century. Some also wonder why the authors’ goal was, first and foremost, focused on private collections of Khmer art, and not dedicated to those neglected museum artworks in the US, or to some of the thousands of pieces stored in the basement of the National Museum in Phnom Penh for lack of exhibition-hall space.

Latchford calls himself “an adventurer-scholar and longtime connoisseur of Khmer Art.” He is known to own a Khmer art collection and to be quite familiar with the art market and private collectors. Bunker, who is an Asian art specialist, is best known in the Khmer-art field for an article she published in the early 1970s on pre-Angkorian, Buddhist sculptures that were found at Prakhon Chai in Northeastern Thailand, which was part of the Khmer empire at the time. She is also a research consultant to the Asian Art Department of the Denver Art Museum in the state of Colorado. Both asked and received cooperation from colleagues in about every museum with an Asian collection in the US. Staff at the Cambodian National Museum shared their knowledge with the authors, and gave them access to their archives during the four years the authors worked on the book.

Bunker and Latchford asked and obtained letters introducing the book from Princess Buppha Devi, minister of Culture and Fine Arts, Khun Samen and Hab Touch, deputy director of the National Museum. In their Authors’ Acknowledgments, Bunker and Latchford mention every museum curator and art specialist who gave them access to their collections and reference material in the course of their research. Still, Bunker and Latchford do say on the second page of their acknowledgments that they are responsible for interpretations and opinions in “Adoration and Glory.” Most Khmer-art experts contacted recognize the care and research that went into this book and are giving the authors the benefit of the doubt.

Their bibliography alone contains nearly 300 titles of works by historians, researchers, ancient Khmer-inscription specialists, experts on image and symbols in Khmer art, traditional-dance historians and many other Khmer-art authorities. “The authors have made use of various means scientific analysis, historical comparison, and knowledge of the art market to present only objects they believe to be authentic,” said Hiram Woodward Jr, who is a curator of Asian Art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, in the state of Maryland. Unlike Indiana Jones, who says in the film “Raiders of the Lost Ark” that “an important artifact belongs in a museum,” Khmer-art experts do not necessarily oppose the private art market. They just wish the owners of artifacts would tell them, and in detail, where their pieces came from and give them access to those pieces, so that researchers could trace their provenance and help expand the knowledge of Khmer art, Porte said.

*Published by Latchford in association with Art Media Resources Inc in Chicago, and printed in Thailand where he lives, Adoration and Glory was released in the US, Europe, Southeast Asia and Hong Kong with a price tag of US$95.

Tags: looted art, replicas, Khmer sculptures, Khmer bronzes, repatriation, trafficking

About the Author

Andy Brouwer

Cheltenham-born and bred, Andy Brouwer (1959, UK) made his first trip to Cambodia in 1994, and that white-knuckle ride hooked him for life. He upped sticks to Phnom Penh in 2007 after more than thirty years in banking back in the UK to join Hanuman Films.

As well as having a serious obsession in temples, books — he’s the editor of the guidebook To Cambodia With Love –, and pretty much all things Khmer, he is a lifetime supporter of Leeds United and has an insatiable passion for the music of Steel Pulse and Ennio Morricone. His website relives his numerous visits to Cambodia, and more.

During his time living in Cambodia, he’s been a producer and researcher for Hanuman Films, a product manager at Hanuman Travel, and the media officer with Phnom Penh Crown FC. Since 2020, he developed a personal research, Exploring Khmer Art Worldwide, published as an ongoing series on his Facebook page, that will be soon hosted on Angkor Database.

Read an interview by Simon Ostheimer (Tales of the Orient, 2020)