Amitabha

sk अमिताभ Amitābha

Buddha of the higher spirit, represented on the headdress of bodhisattvas.

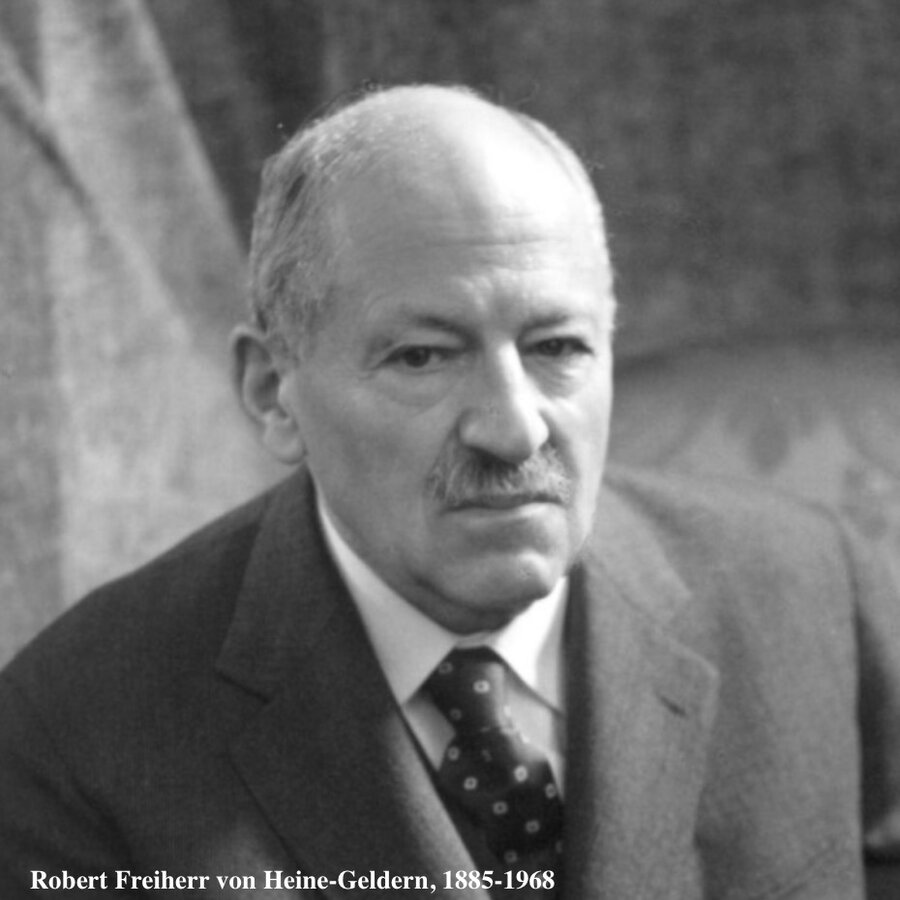

by Robert Heine-Geldern

pdf 3.4 MB

This revised version of an article published in The Far Eastern Quarterly (Vol. 2, November 1942: 15 – 30) develops a dynamic approach to the much debated question of the state formation process in Southeast Asia. True to his method, the author compared kingship representations across the region, from Burma to Bali with an emphasis on the Khmer “Empire” — the imperial concept was still predominant in the academic circles at the time.

In Southeast Asia, even more than in Europe, the capital stood for the whole country. It was more than the nation’s political and cultural center: it was the magic center of the empire. The circumambulation of the capital formed, and in Siam and Cambodia still forms, one of the most essential parts of the coronation ritual. By this circumambulation the king takes possession not only of the capital city but of the whole empire. Whereas the cosmological structure of the country at large could be expressed only by the number and location of provinces and by the functions and emblems of their governors, the capital city could be shaped architecturally as a much more “realistic” image of the universe, a smaller microcosmos within that macrocosmos, the empire. The remains of some of the ancient cities clearly testify to the cosmological ideas which pervaded the whole system of government. Fortunately, a number of inscriptions and some passages in native chronicles may help us in interpreting archaeological evidence.

As the universe, according to Brahman and Buddhist ideas, centers around Mount Meru, so that smaller universe, the empire, was bound to have a Mount Meru in the center of its capital which would be if not in the country’s geographical , at least in its magic center. It seems that at an early period natural hillocks were by preference selected as representatives of the celestial mountain. This was still the case in Cambodia in the 9th century A.D. Yesodharapura, the first city of Angkor, founded towards 900 A.D., formed an enormous square of about two and a half miles on a side, with its sides facing the cardinal points and with the Phnom Bakheng, a small rocky hill, as center. An inscription tells us that this mountain in the center of the capital with the temple on its summit was “equal in beauty to the king of mountains,” i.e. to Mount Heru. The

temple on Phnom Bakheng contained a Lingam, the phallic symbol of Siva, representing the Devaraja, the “God King,” i.e. the divine essence of kingship which embodied itself in the actual king. More frequently the central mountain was purely artificial, being represented by a temple only. […] In ancient Cambodia a temple was quite ordinarily referred to as “giri”, mountain, and the many-tiered temples of Bali are still called Meru. The Cambodian inscriptions are very explicit with regard to such identifications. Thus, to give an example, one of them says that King Udayadityavarman II (11th century), “seeing that the Jambudvipa had in its center a mountain of gold, provided for his capital city, too, to have a golden mountain in its interior. On the summit of this golden mountain, in a celestial palace resplendent with gold, he erected a lingam of Siva.” [p 3]

As researchers still debated the mystical signification of the four-faced towers, the author gave an interpretation that has since gained precedence — note the strictly ‘Hinduist’ explanation for the naga balustrades, leaving aside the local origin of the devotion for the naga :

As Jayavarman VII was an adherent of Mahayana Buddhism, the central “mountain” in this case was a Buddhist sanctuary, which contained a large image of the Buddha Amitabha, while the four faces of Bodhisatva Lokesvara, the “Lord of the World,” adorned its numerous towers. The city was surrounded with a wall and moat forming a square almost two miles on each side, its sides being directed towards the four cardinal points. There are gates in the middle of each side and a fifth one on the East leading to the entrance of the royal palace. The towers above the gates are crowned with the same four-fold faces of Lokesvara as those of the central temple. Thus, that smaller world, the city of Angkor, and through its means the whole Khmer empire were both put under the protection of the “Lord of the Universe.” The cosmic meaning of the city was further emphasized

by a curious device. The balustrades of the causeways leading over the moat to the city gates were formed by rows of giant stone figures, partly gods, partly demons, holding an enormous seven-headed serpent. The whole city thus became a representation of the churning of the primeval milk ocean by gods and demons, when they used the serpent king Vasuki as a rope and Mount Meru as churning stick. This implies that the moat was meant to symbolize the ocean, and the Bayon, the temple in the center of the city, on which all the lines of churning gods and demons converged, Mount Meru itself [p 4].

A prevalent notion amongst Anglo-Saxon scholars — and writers of fiction — was that Southeast Asian kings always had four “principal wives”:

Thus the stage was set for the enacting of the cosmic roles of king, court and government. He may choose Burma as an example. There, the king was supposed to have four principal queens and four queens of secondary rank, whose titles, “Northern Queen of the Palace,” “Queen or the West,” “Queen of the Southern Apartment,” etc., showed that they originally corresponded to the four cardinal points and the four intermediary directions. There are indications at at an earlier period their chambers actually formed a circle around. the hall of the king, thereby emphasizing the latter’s role as center of the universe and as representative of Indra, the king of the gods in the paradise on the summit of Mount Meru. Sir James George Scott’s observation that King Thibaw’s (the last Burmese king) failure to provide himself with the constitutional number of queens caused more concern to decorous, law-abiding people than the massacre of his blood relations, shows how important this cosmic setting was considered to be. There were four chief ministers, each of whom, in addition to their functions as ministers of state, originally had charge of one quarter of the capital and of the empire. They obviously corresponded to the four Great Kings or Lokapalas, the guardian deities of the four cardinal points in the Buddhist system. However, the task of representing the four Lokapalas had been delegated to four special officers, each of whom had to guard one side of the palace and of the capital. They had flags in the colors attributed to the corresponding sides of Mount Meru, the one representing Dhattarattha, the Lokapala of the East, a white one, the officer representing Kubera, the Lokapala of the North, a yellow flag, etc. The cosmological principle was carried far down through the hierarchy of officialdom, as revealed by the numbers or office bearers. Thus, there were four under-secretaries of state, eight assistant secretaries, four heralds, four royal messengers, etc. Very much the same kind of organization existed in Siam, Cambodia and Java. Again and aeain we find the orthodox number of four principal queens and of four chief ministers, the “four pillars” as they were called in Cambodia, In Siam, as in Burma, they originally governed four parts or the kingdom lying toward the four cardinal points. [p 5]

From Burma, the author reported a legend that strikes by the similarity with the story of “Ta” Trasak Paem តាត្រសក់ផ្អែម [‘Grandpa Sweet Cucumber’, also called King Ang Chay ព្រះបាទ អង្គជ័យ] in 14th century Cambodia, another regicidal gardener who was considered by King Norodom Sihanouk as the founder of the Varman dynasty, and thus as his ancestor. In 1961, Prince Sihanouk noted that his 1955 decision to abdicate the throne in order to lead the Sangkum Reastr Niyum showed, “according to many, that I was as courageous and energetic as “Ta” Trasak Paem”[Rapport au peuple khmer au terme de mission en Amérique et aux Nations Unies, Phnom Penh, Imprimerie du Ministère de l’Information, 1961, 111 p.]:

In Hinayina Buddhism the idea of divine incarnation as justification of kingship is replaced by that of rebirth and of religious merit. It is his good karma, his religious merit acquired in previous lives, which makes a man be born a king or makes him acquire kingship during his lifetime, be it even by rebellion and murder. A typical instance is that of King Nyaung‑u Sawrahan (10th century) as told in the Glass Palace Chronicle of the Kings of Burma. Nyaung‑u Sawrahan, a farmer, kills the king who has trespassed on his garden and whom he had not recognized. Thereupon he is himself made king against his wish. So strong is his karma that, when one of the ministers objects to his installation, the stone statue of a guardian deity at the palace door becomes alive and kills the minister. The chronicle’s comment is significant: “Although in verity King Sawrahan should have utterly perished, having killed a king when he was yet a farmer, he attained even to kingship simply by strong karma of his good acts done in the past.” But the moment the karma of his past good acts is exhausted, that same stone statue which formerly had killed his adversary becomes alive again and hurls him from the palace terrace.

No merit could exceed that of a service rendered to the Buddha himself. Thus the Glass Palace Chronicle tells us that the ogre-guardian of a mountain, who had shielded the Buddha from the sun with three leaves, had received from the latter a prophecy that he would thrice become king of Burma. In the 10th century he is reborn in lowly surroundings as Saleh Ngahkwe, who later becomes king by murdering his predecessor and, “being reborn from the state of an ogre, was exceedingly wrathful and haughty,” indulging in gluttony and sadistic murder, till he is at last killed by his own ministers. One should think that the merit of having shaded the Buddha would have been exhausted by a life full or crimes. However, according to the Burmese chronicle, this is not so. The former mountain spirit is reborn in the 12th century as Prince Narathu who becomes king by murdering his father and brother and throughout his reign excells by bloody deeds, and in the 13th century as king Uarathihapate. This leads us to a very characteristic conception of historical events as based on the enormous importance attributed to prophecies and portents. [p 9]

And the closing lines of the study, written at a time of international instability, seems to reverberate into the 2020s:

A sudden complete break of cultural traditions has almost always proved disastrous to national and individual ethics and to the whole spirit of the peoples affected. A compromise between old and new conceptions therefore would seem desirable. Many, at least, of the outward expressions of the old ideas could easily be kept intact and gradually filled with new meaning, without in the least impairing educational and material progress. After all, the case of Japan shows that an idea decidedly more primitive than that of the cosmic state and less adaptable to ethical reinterpretation than the latter, the belief in the descent of the Mikado from the Sun Goddess (or at least the fiction of such belief) may very well survive and coexist with all the refinements of modern science and technique. The current problems of Southeast Asia hitherto have been discussed almost exclusively from the point of view of economics and of political science. It would be a grave mista.ke to disregard the importance of native culture and tradition for a future satisfactory reorganization of that regian. [p 13].

Photo: Phnom Bakheng, 2008, by Sutibu.

Tags: devaraja, temple-mountain, capital cities, state formation, Bali, Burma, founding myths, modern history

Robert Heine-Geldern [Robert Freiherr von Heine-Geldern before 1919] (16 July 1885, Grub, Wienerwald — 25 May 1968, Vienna, Austria) was an Austrian anthropologist, ethnologist, archaeologist and prehistorian specializing in Southeast Asia, a professor of ethnology and archaeology of India and Southeast Asia at the University of Vienna and in the USA when he had to flee his country from 1938 to 1949.

A young relative of famous German poet Heinrich Heine, Geldern studied art history and philosophy at Munich University and the University of Vienna, still the capital city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. After a field trip to the India – Burma border in 1910, he majored in in anthropology and prehistory with a 1914 doctoral thesis on the Mountain Tribes of Northern and Northeastern Burma.

Immediately after WWI, Heine-Geldern joined the ethnographic department of the Natural History Museum (later Museum of Ethnology) in Vienna (from 1917 to 1927), starting with other researchers an ongoing effort to combine ethnology and prehistory aiming at a “universal historiography” and pioneering the field of Southeast Asian anthropology. A lecturer in ethnology applied to Southeast Asia and India at Vienna University since 1927, he was appointed associate professor for Ethnology and Archaeology of India, Southeast Asia and Oceania in 1931.

Fleeing the Nazi persecutions, he decided not to return to Austria from a lecture tour in the United States in March 1938, a refugee in New York Cit who started to work at the anthropological department of the American Museum of Natural History and teach at New York University and Columbia University. Co-founder of the anti-fascist Austrian-American League with Irene Harand in 1939, he launchedd in 1941 the East Indies Institute of America (later Southeast Asia Institute) together with anthropologists Margaret Mead, Ralph Linton, Adriaan J. Barnouw and Claire Holt.

From 1943 to 1949, he was a professor at New York Asia Institute in New York, before returning to Vienna and being reinstated as associate professor of Asian prehistory, art history and ethnology in 1950. He led Vienna University’s Institute of Ethnology until his retirement in 1958, and continued to work as Emeritus Professor until his death.

Respected both by prehistorians such as Madeleine Colani and ethnologists, Heine-Geldern contributed to develop multidisciplinary Southeast Asian studies, for instance with his reference essay on the “Conceptions of State and Kingship in Southeast Asia” (1942). He was a member of several learned societies: Austrian Academy of Sciences, Royal Asiatic Society, Royal Anthropological Institute, and École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO).

Heine-Geldren also tackled the hypothesis of pre-Columbian transpacific contacts between the American and Southeast Asian continents. As Erika Kaneko noted in 1970, “hen he firstbroached the subject it was anathema, but thanks to the vast bulk of evidence brought forth in favor of such contacts by him and scholars encouraged by his work, the prejudices have decreased (op. cit, p 6). His contributions on that subject have been criticized, even he never ventured to the extremity shown by some authors who argued that early American tribes should be considered as “Asiomericans”. However, in his preface to L.P. Briggs’ The Ancient Khmer Empire (1951), he wrote

The exhibition shown by the American Museum of Natural History on the occasion of the International Congress of Americanists in 1949, opened a completely new chapter by demonstrating the existence of cultural links, surprisingly close in some instances, between the Maya and Mexican area and ancient Cambodia. These contacts seem to have been established at the time of the kingdom of Funan and to have ended only with the political collapse of the Khmer empire shortly after A.D. 1200. They imply the former existence of a powerful Khmer maritime activity, of which we had, so far, only a few vague indications in old Chinese reports.”