Death and Mortuary Rituals in Mainland Southeast Asia: From Hunter-Gatherers to the God Kings of Angkor

by Charles F. H. Higham

A journey in time from elite burial rituals in the Neolithic Age to the "temple mausolea" of Angkor.

- Publication

- Chap 17 in ‘Death Shall Have No Dominion: The Archaeology of Mortality and Immortality’, ed Colin Renfrew, Michael J. Boyd, Iain Morley, Cambridge University Press, pp 280-300

- Published

- November 2015

- Author

- Charles F. H. Higham

- Pages

- 20

- Language

- English

pdf 1.5 MB

In mailand Southeast Asia, the continuity of burial rites through the ages, with its culmination in the “temple mausolea” of Angkor, is remarkable. In this essay, the author, interpreting Bronze Age cemeteries together with their Neolithic predecessors and Iron Age successors, stresses “the provision of mortuary feasting in both securing and maintaining the social status of the relatives of the deceased. This may be seen in the placing of lidded pottery containers in graves with fish, shellfi sh, chickens, eggs, pigs, cattle, and water buffalo bones in graves. In this manner, the dead served the living elite, a practice that might have been enhanced when the bones of particularly rich Bronze Age grandees were exhumed perhaps to participate in post mortem rituals, and then carefully reinterred.”

The social role of mortuary rites culminates in the Angkorean civilization. The historic process is described as follows: “With the opening of the Southern Maritime Silk Road, exotic goods and ideas reached Southeast Asia. The established elites found in the esoteric Hindu religion an ideological pathway to elevated social status that progressively moved them closer to divine status. By the seventh century, just two centuries after the last Iron Age leaders were interred at Noen U‑Loke, a Khmer king was accorded a title hitherto employed only for gods. With the foundation of the Kingdom of Angkor in the early ninth century, texts inscribed for royal temple mausolea accord the rulers divine titles. Ancestors likewise were worshipped. The construction of increasingly massive temple mausolea, such as Angkor Wat and the Bayon, engaged armies of stone masons, sculptors, architects, priests, goldsmiths, and labourers in a common endeavour whereby merit was gained through contributing to the tomb of a god. In this manner, it is possible to identify in the Angkorian monuments the physical evidence for the exploitation of the populace by the ruling line. One of the particular features of this behaviour is the stress placed upon legitimacy through descent from the divine ancestors. The temple of Preah Ko at Hariharalaya, for example, has six shrines, each dedicated to the worship of King Indravarman’s male and female ancestors.”

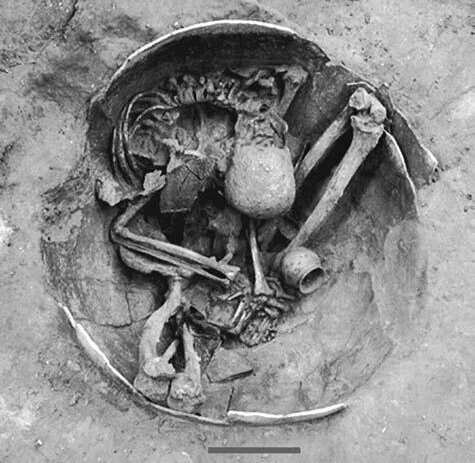

Photo: Neolithic male jar burial at Ban Na Di site, upper Mun Valley (by the author)

Tags: prehistory, Bronze Age, burial, mortuary rites, Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm, religion, cult of ancestors, Iron Age, Jayavarman VII, archaeology, jars, social history, elites, Preah Ko

About the Author

Charles F. H. Higham

Charles Frank Wandesforde Higham (UK, 1939), a research professor at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, and a member of the British Academy, is a prolific archaeologist most noted for his work in Southeast Asia, including the neolithic sites of Northeast Thailand and the Angkorian civilization.

His current research involves excavations at the Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak, Thailand, where he has identified an extensive area comprising the residential quarter of an Iron Age town, complete with houses, a lane, an iron working area and several ceramic kilns.

In conjunction with other researchers, he has linked a period of increased aridity with the start of an agricultural revolution that stimulated the rise of early states in Southeast Asia. In July 2018, he was a co-author of a pioneering publication on ancient human prehistoric DNA from several sites in Southeast Asia. The result identified a series of population movements beginning with the arrival of anatomically modern humans over 50,000 years ago.