From “Originals” to Replicas: Diverse Significance of Khmer Statues

by Keiko Miura

How Hindu or other objects of earlier periods have been worshipped as neak tā by the communities living nearby the Khmer temples.

- Publication

- Göttingen University Press| Open Books Edition 2017 (Series on Cultural Property)

- Published

- 2015

- Author

- Keiko Miura

- Pages

- 26

- Language

- English

pdf 1.1 MB

The author starts her exposé by reminding us that various restoration campaigns happened in Angkor way before the colonial times: “The best-known restoration was one described in inscriptions that King Sitha restored Angkor Wat (meaning a “City Temple”) in 1577 – 1578. His mother, overjoyed with her son’s devotion, pledged to restore the Buddha statues in the Bakan. Another case is that of an enormous stone statue of the four-faced Buddha that was lost in Longvek, the capital after the fall of Angkor, leaving only four pairs of feet, after the Siamese attack in 1594. The plundered statue was replaced by a replica, though much smaller, and has been a place of worship for Cambodians until today.”

Legally speaking, the general term for cultural property in Khmer is sâmbat wabbathor -សម្បត្តិវប្បធម៌ -, which is distinct from that for cultural heritage, ker morodâk — កេរ្តិ៍មរតក -, ker dâmnael — កេរ្តិ៍ដំណែល - , and more recently, petekaphoan wabbathor — បេតិកភណ្ឌ វប្បធម៌ -. The author shows that, in Cambodian minds, the distinction between ‘original’ and ‘replica’ artworks is not really significant, the main value of statues being how they hold local spirits, neak ta.

Note: An interesting insight on the history of the Angkor Conservation Office in Siem Reap: “The depot of the Angkor Conservation Office under the auspices the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts has the largest collection of Khmer art in the world. It also houses some offices and laboratories of foreign conservation teams that do not have their own independent facilities in the city. With the changing socio-political environment, however, the Angkor Conservation Office has gradually reduced the number of objects stored because of vandalism and the transfer of some objects to other newly opened museums in the country. In addition, the Angkor Conservation Office has slowly shifted its area of operations as well as parts of its former functions since Angkor’s World Heritage nomination in 1992. The establishment of the APSARA Authority in charge of the development and management of Angkor and Siem Reap in 1995 curtailed the field of activity of the Angkor Conservation Office. The management of fairly large and important heritage sites, such as Angkor and Koh Ker, was transferred to the APSARA Authority and, prior to the World Heritage nomination of Preah Vihear, to the Preah Vihear Authority. The repository of the Angkor Conservation Office looks like a mausoleum of antiquities today, with many fragments and broken figures with missing parts, i.e. heads, torsos, feet, arms, etc. The sight reminds us of countless acts of vandalism in the Angkor heritage space. The Angkor Conservation Office itself was also subjected to vandalism, despite the fact that the most precious objects had been transferred to the National Museum in Phnom Penh in 1967 (Ang et al. 1998: 104).Hundreds of objects disappeared during the civil war and unstable periods between 1970 and the early-1990s; direct attacks were conducted by armed soldiers between 1970 and 1975, between 1976 and 1977, and between 1992 and 1993.”

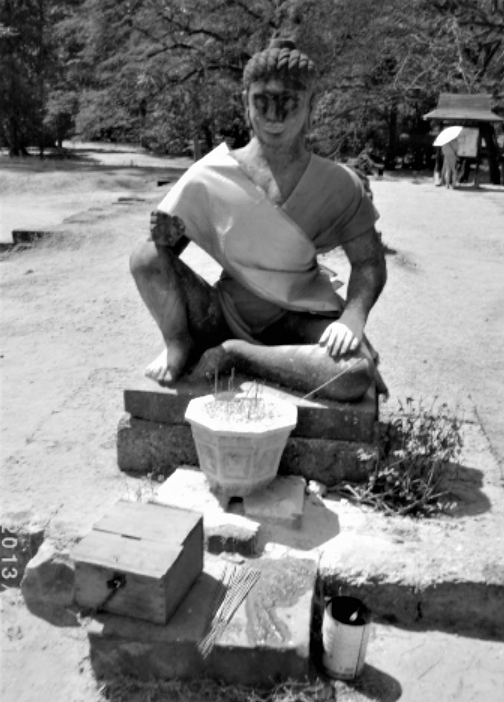

Photo: A replica of the Leper King statue in Angkor Thom, 2013 (author’s photo).

Tags: sculpture, King Sitha, Queen Mother Monineath, cultural property, heritage conservation, statues, Angkor Conservation

About the Author

Keiko Miura

Keiko Miura had worked in the Culture Unit of UNESCO Office in Cambodia from 1992 to 1998, with approximately 6‑month interval working with UNESCO/Japan Funds-in-Trust project (JSA) for archaeological and anthropological work.

After resigning UNESCO, she became engaged in a Ph. D research on the relationship between Angkor heritage and local communities at the Dept. of Social Anthropology, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. On completing her Ph. D in 2004 she has been teaching at several Japanese universities while conducting a follow-up research in Angkor and a Balinese agriculture and rituals.