Jayavarman VII's 'Resthouse Temples'

by Mitch Hendrickson

'People Around the Houses with Fire: Archaeological Investigation of Settlements Around the Jayavarman VII 'Resthouse' Temples'

- Publication

- University of Sydney. Abstracts in Khmer and French

- Published

- 2008

- Author

- Mitch Hendrickson

- Pages

- 17

- Language

- English

pdf 5.2 MB

Recent researches on the ‘dharmasala’ buildings (translated as fire shrine, house of fire, resthouse, maison d’etape, gite, maison de feu…)give us a better understanding of their social and religious functions.

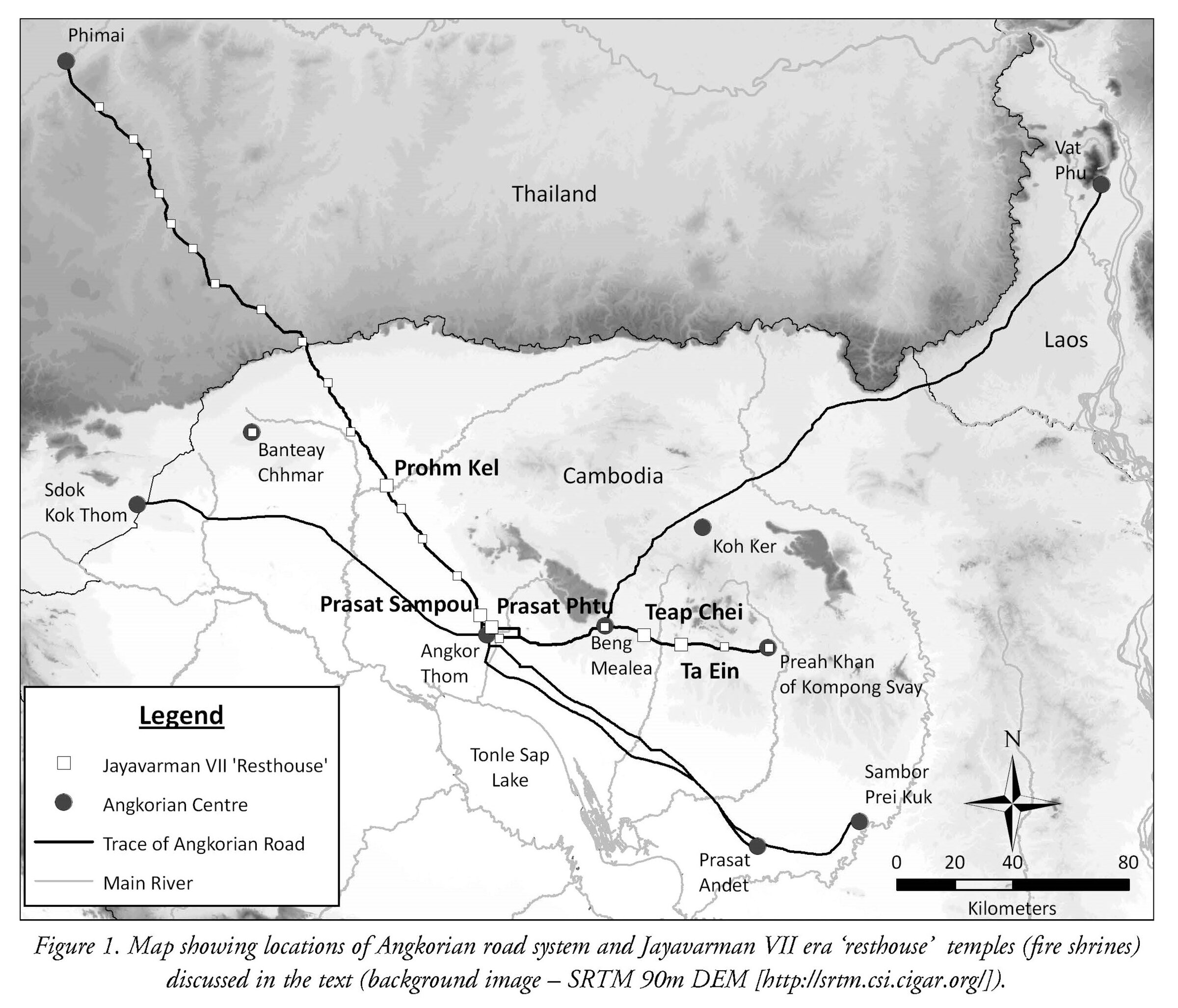

On the main Angkorean roads (to Phimai — northwestbound –, to Kompong Svay — eastbound — and to Laos– northeastbound –), it has now been agreed that “fire shrines” or ‘resthouse temples’ were established and spaced along the way at regular interval, precisely 14.8 or 16.1 km depending on the orientation of the fareways.

After discussing previous interpretations, the author summarizes the latest findings by writing that “discovery of occupation, water storage and production centres demonstrates that fire shrines are not isolated temples ignored by travellers and pilgrims on their travels to and from Angkor. The fire shrines represent the most visible feature of a greater complex within the Angkorian landscape (…) Further work will no doubt shed more light on the important religious, political, economic and social roles that these buildings played in Angkorian society.”

Other remarks in the study:

- Evidence of “resting places” associated with the Cambodian transport system is commonly found from the Angkorian period to the modern day. During the dry season watering locations and shelter are an essential part of facilitating regional communication and are repeatedly mentioned in historic records. The late 13th century account of Zhou Daguan mentioned the presence of samnak (rest stops). While he does not actually describe the Jayavarman VII era structures, he compares them to Chinese post halts found along their main highways. Six centuries later, European explorers repeatedly refer to rest stops or salas during their travels through Cambodia. Bastian, for instance, records staying at wooden salas variably located beside ponds, rivers, monasteries or outside villages. Mouhot commented on the frequency of royal ‘stations’ spaced approximately 20 km apart for the king on the route between Kampot and Udong. Albrecht’s survey along one of the Southeast roads refers to a local tradition that the Southeast road from Angkor had a series of étapes d’éléphant (elephant stops) marked by a monument. Unfortunately, no trace of these buildings remains as locals informed Albrecht that the Thai destroyed these edifices during their control over the region. [1]

- The regular spacing between the fire shrines not only provides evidence that they served a practical purpose but indicates how far people travelled in the Angkorian past. Groslier suggested that 25 km was an average distance per day; based on the data calculated here travel along the roads appears to be slightly longer at 30 km, with the fire shrines acting as midday and evening halts, or substantially shorter at 15 – 16 km. If we assume the former distance is a better correlate the real-time trip between Beng Mealea and Preah Khan of Kompong Svay would be approximately two to three days. Excluding the time required to travel up/down the Dangrek Range it would take four to five days to reach the escarpment from Angkor and a further four and a half to five and a half days to reach Phimai.”

- Both the sandstone and laterite ‘resthouse’ structures are attributed to the late 12th to early 13th

century and, most likely, to the reign of Jayavarman VII (1181−1220 CE). This chronological association is

derived primarily from the Preah Khan stele dated to 1191 CE (see Coedès 1941) and the decorative use of the Lokesvara motif. The stele describes a series of 121 vahni-griha found along three roads and in specific Angkorian temple enclosures; the correlation of the 17 vahni-griha listed to Vimaya (Phimai) corroborates the number found along the Phimai road (Ibid.). The Lokesvara motif, which represents the Buddha of healing, is associated with the switch to Buddhism as state religion for Jayavarman VII and his successor Indravarman II (1220−1270 CE).

The data presented here demonstrates that fire shrines were an integral piece of Khmer transport

infrastructure. Written accounts from the 13th to 19th centuries show that resting places for travellers and the ruling elite have a long history in Cambodia. Lunet de Lajonquière recognized the spacing and orientation of the fire shrines, characteristics that separate them from other Khmer temple types. Remeasuring the distance between the fire shrines both corroborates this interpretation and additionally indicates that travellers were able to move at an average of 30 km per day along Angkor’s main roads.

Completion of the first comprehensive excavation and surveys around the fire shrines demonstrates

that while they were ‘islands’ of Khmer state control, the area around them was far from isolated and/or

uninhabited. Test trenches at Prasat Sampou and Prasat Phtu produced subsurface features (cooking

remains, foundation) that, based on the ceramics and 14C AMS date, correspond with the era of Jayavarman VII and the inscription-derived construction of the laterite fire shrines. The range of Khmer

earthenware and stoneware indicates domestic and ritual activities were taking place while the presence of imported Chinese wares allows us to suppose transmission along the road system to the site, integrating it with broader Khmer trade networks.

A more intriguing result is the recurring presence of infrastructure in the form of ponds,

embankments, and walls around the fire shrines. Water storage is a ubiquitous feature in almost all

Angkorian building works and it is not surprising that ponds were frequently recorded during the surveys.

Though the ponds are not yet directly dated it is safe to presume that they were built in response to the

needs of the fire shrine. Differences in shape and distribution could be related to concern for assisting

travellers and traders rather than meeting the official requirements for religious and/or political elite.

Conversely, the position of the fire shrine may be related to pre-existing natural springs or low-points in

the landscape suitable for water storage. The appearance of walls and low embankments is further evidence that the fire shrines are part of a complex and not isolated temples. Unlike the hospital chapels, the infrastructure around each fire shrine is much more varied and relied not on masonry but perishable construction materials.

- Claude Jacques, a strong proponent of the religious function of fire shrines, conceded the important point

that we need to identify the function of these buildings in order to better understand the role of the

Angkorian roads (see Jacques and Lafond 2004: 286). Since we are restricted to historic records of the

‘sacred fire’ that was purported to have been stored at these temples, we are left to explore their concurrent purpose as a resting place within the transportation system from archaeological evidence. Findings presented here from historic documents, excavation, and surveys have successfully identified their secular role as a type of ‘resthouse’ temple. Discovery of occupation, water storage and production centres demonstrates that fire shrines are not isolated temples ignored by travellers and pilgrims on their travels to and from Angkor. The fire shrines represent the most visible feature of a greater complex within the Angkorian landscape. With clearance of land mines from around these sites, further work will no doubt shed more light on the important religious, political, economic and social roles that these buildings played in Angkorian society.

[1] Albrecht, M. 1905. « Reconnaissance de l’ancienne chaussée khmère ». Bulletin de la Societé des Études Indochinoises, Saigon: 3 – 17.

Main photo: a fire shrine at Preah Khan near Angkor.

Tags: royal roads, transportation, dharmasala, fire worship, fire shrines, Jayavarman VII

About the Author

Mitch Hendrickson

Associate Professor at the UIC-Department of Anthropology (Chicago, USA), researcher at the Department of Archaeology, University of Sydney, Australia, Mitch Hendrickson is a landscape archeologist active on various Angkorean sites.

He is the Director of Industries of Angkor Project, Co-Director of the Two Buddhist Towers Project and the Iron and Angkor Project.