Jewels For A King

by Claudine Bautze-Picron

Stylistic relationship between Khmer architectural ornamentation and jewellery, and its South-Indian influences.

- Publication

- Indo-Asiatische Zeitschrift, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, Vol. 14, pp 42-57 | Part 1

- Published

- 2010

- Author

- Claudine Bautze-Picron

- Pages

- 14

- Language

- English

pdf 2.0 MB

In 2022 and 2023, the restitution to Cambodia of stunning pieces of jewelry and gold artefacts that had been looted in the past has cast a new light on the subject. Written in 2010, the present study could not have taken in consideration that the very ‘experts in Khmer art’ whose work was still a reference, namely Douglas Latchford and Emma Bunker, were those who had tucked away or illegaly such artefacts.

And so, notes the author in the Introduction,

When Indian gods and goddesses reached Southeast Asia, their original images underwent deep transformations. This is particularly perceptible in the region which once formed the Khmer kingdom: The iconography got there much simplified, the number of forms shown by the deities – practically numberless in India – was extremely reduced, and the ornamentation became plain. The Indian perception of the divine is to depict its overwhelming luxuriance, its fullness, its abundance,

whereas the Southeast Asian aesthetics rather emphasizes sobriety in the ornamentation and restraint in the movements as befitting a deity. In South Asia, images were also at the focus of rituals involving their apparel and adornments. Such rituals apparelled with human-made clothes the image of a deity already fully dressed and richly adorned with jewellery on all parts of the body. Although the artist created an (apparently) dressed image, the cult image was always felt to be “naked” for the human eyes, calling for its clothing with “real” dresses and jewels, a tradition inherited by countries penetrated by Indian culture. In Southeast Asia like in their country of origin, the body of gods and goddesses was thus hidden by real clothes and jewellery.

“Ancient gold jewellery is rarely discovered, for evident reasons: items were recast, reused, looted, or destroyed. However, from a very early period, goldsmiths have revealed a great skilfulness, drawing most probably their knowledge from Indian masters. Dating back to an earlier period than the one considered here and betraying South Asian iconographic features, golden jewels or plaques that were embossed, forged or more rarely cast, have been excavated in sites located in the ancient kingdom

of Fu-nan.[…] Pre-Angkorian jewellery of the sixth through ninth centuries remains similarly rare. The few in-situ discoveries made a long time ago are little documented and have tragically been looted from the National Museum in Phnom Penh in the 1970s without their present whereabouts being known; such is the case of three belts discovered at Kbal Romas, Kampot, Chruy Angkor Borei,

Takeo, and Udong, north of Phnom Penh. More recently, examples of gorgeous pieces of jewellery variously dated surfaced without unfortunately their precise findspot being documented (MCCULLOUGH 2000; BUNKER 2000; BUNKER/LATCHFORD 2008).

Later, the author notes: ‘As early as 1933 and 1934, Gilberte de CORAL-RÉMUSAT had underlined the closeness of ornamentation and composition of pre-Angkorian and Indian lintels; later, Mireille BÉNISTI showed in a series of articles published in Arts Asiatiques between 1968 and 1974 how the Khmer decorative ornamentation traced its origin back in South Asia, summarizing a large part of her findings in her publication of 1970. From their research, it is obvious that the main period during which the Indian influence found its way to Southeast Asia, more particularly to the country of the Khmers, broadly spread between the fifth and the seventh centuries.’

However, adds she, ‘the aesthetics of the Khmers deeply differs in its sobriety from the genuine and deep feeling for the flowing movement and the extraordinary ornamentation which characterize the images of Indian gods and goddesses. These images are richly dressed with jewels from the very first moment of their creation by the artist, which is not the case among the Khmers.’

The Chalukya Influence

The Chalukya (earlier Badami Chalukya) dynasty was a powerful actor in ancient South India, often waging wars against the Chola and the Pallava dynasties. On that subject, the author notes that

The choice and treatment of specific motifs find matching examples in Cålukya architectural ornamentation from the sixth to seventh centuries and similar pieces of jewellery are encountered in the sculpture of the period„ which corroborates what had been already surmised at a more general level by various authors evoking the influential relationship between the Cålukyas and Southeast Asia. And this allows even delineating with more precision the geographical location of the source of inspiration of these jewels within a vast region spreading from Maharashtra to Tamil Nadu from where numerous examples of (decorative) motifs found their way in Khmer art.

Cambodian Gems Abroad

Even if this is not in the scope of the present study, we add the following note regarding early trading of precious stones extracted in what is now Cambodia, and in particular the blue shappires from Pailin area.

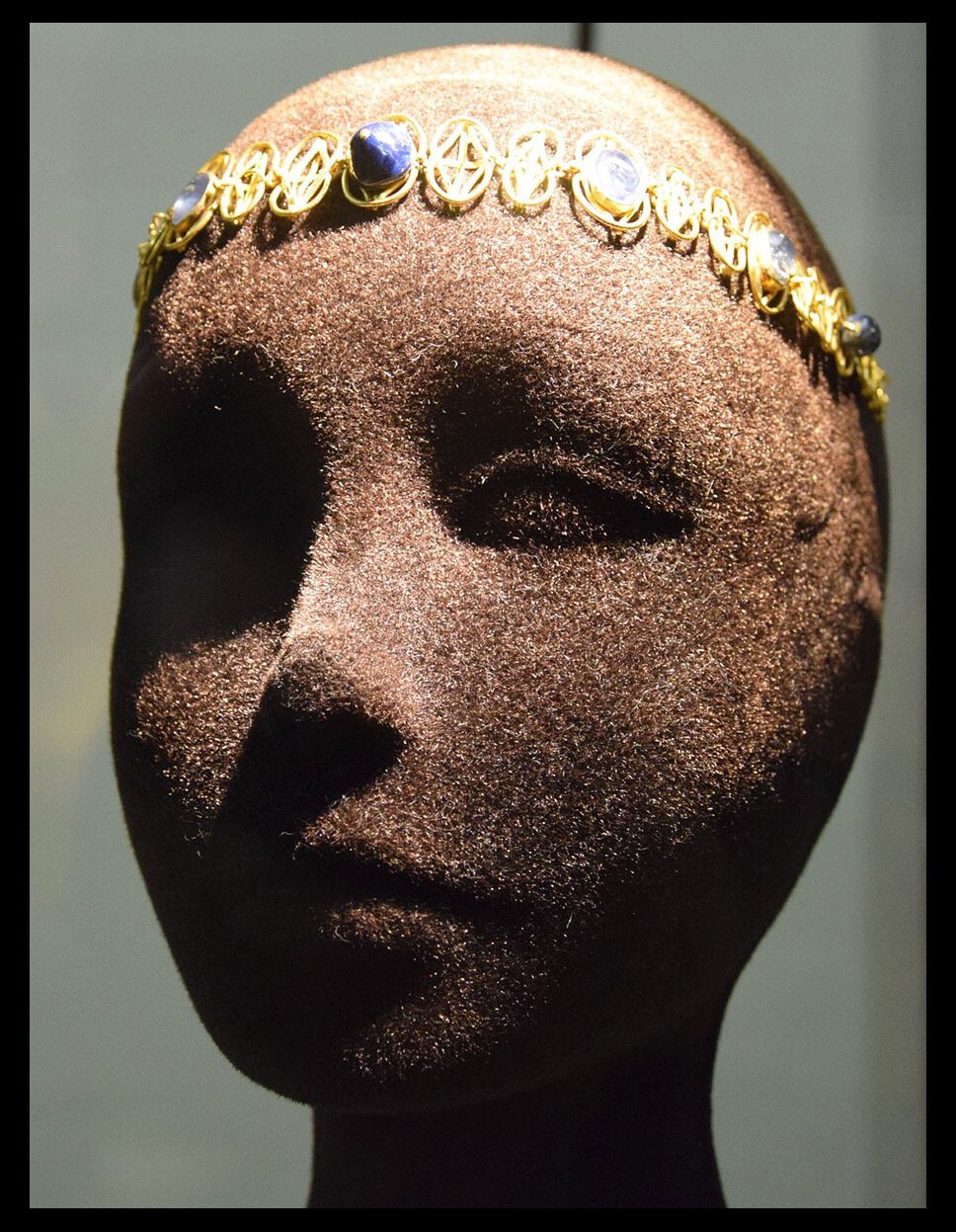

Regarding the extraordinary diadem found in 2011 within the tomb of a high-ranking female in the necropolis of San Quintino in Colonna, dated to the 2nd century CE, and currently on display in the Archaeological Museum in Palestrina outside Rome, Italy, Andy Brouwer remarked: “It is 29 centimeters long, and contains seven sapphires, amounting to 46.2 carats. The chain necklace is made of gold with simple Hercules knots alternating with fixing links bearing the gemstones. What’s so extraordinary is that the National Institute of Gemology in Italy believe the sapphires are from Southeast Asia and almost certainly from Cambodia. That suggests trading routes from early Cambodia all the way to the Mediterranean and Europe, within the late Iron Age period (with the deep blue sapphires from Pailin the most obvious source).”

Photo: Ring or pendant, Khmer jewelry, private collection (©Joachim K. Bautze)

Tags: crafts, jewellery, jewelry, Khmer Empire, Khmer Kings, Indian influences, art history, sculptural art, gems, Funan

About the Author

Claudine Bautze-Picron

Indian Art historian Claudine Bautze-Picron has studied artworks in Bihar, West Bengal, Bangladesh, and Southeast Asia, focusing on Buddhist iconography.

A researcher with CNRS (France), she has authored books book on mural carvings and paintings at Pagan (Burma/Myanmar), and The Bejewelled Buddha, From India to Burma, (Sanctum Books, New Delhi/Kolkata, 2010).

She also teaches Indian Art History at the Department of Art History and Archaeology, Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, Free University of Brussels (Belgium).