gopura

sk गोपुर gopura, "elaborate gateway" |

Gopura in Indian architecture refers to a tower above a gateway or archway, "towers at the entrances of a temple". The term is also used as saṃdoha, a "meeting place" of the Yoginis.

by Andrew Spooner

An exploratory description of ancient Khmer temples in the historic Khet Bati (Bati Province), visited in 1877 by an amateur archaeologist.

pdf 961.2 KB

Merchant, businessman and economic advisor to the French colonial authorities, Andrew Spooner was also a tireless explorer of Cambodia who had reached Angkor as early as 1862, traveling with General Bonard. On 22 Dec. 1877, leading “a cortège of eleven elephants” with a Cambodian official (named “Présor-Sorivong”, “one of King Norodom’s ministers”), one interpetrer and several coolies, he left Phnom Penh on the “dusty” road to Kampot, turning west at some point to reach Phnom Chisor ភ្នំជីសូ, ignoring the admonestations of his Cambodian companions to make a detour in order to “skip the Neac-Ta of the mountain.”

The explorer is now in the heart of Bati Province, a lesser-known region despite its closeness to the capital city. In A‑B de Villemereuil’s Explorations et Missions de Doudart de Lagrée, French Protectorate official and researcher Jean Moura noted that

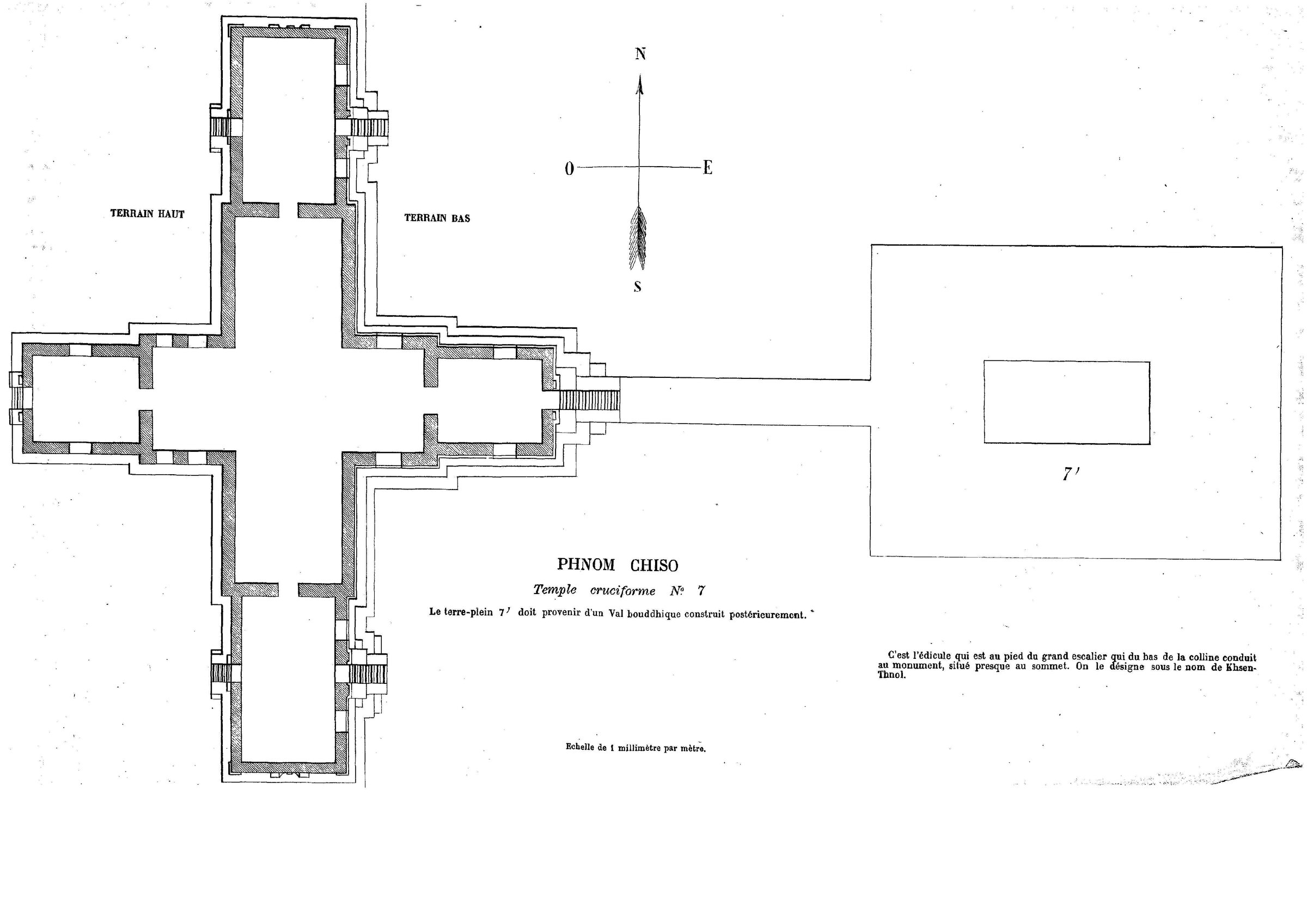

“Khet Bati [province comprise dans la grande division de Treang] tire son nom d’un lac que les Cambodgiens appellent lac de beau lieu, tonlé Bati. Elle renferme des ruines que nous avons explorées en avril 1874. Près du lac, un temple du genre de celui de Phnom Bachey, et, comme devant ce sanctuaire, une pierre isolée portant une inscription votive de 1496 de l’ère de Bouddha, soit 953 de J.-C., de 8 ans postérieure à celle de Phnom Bachey. […] Le très-important sanctuaire du phnom Chiso, auquel on accédait par un escalier gigantesqne de 380 marches, qui devait relier le sanctuaire à un centre habité dont il reste un sala et d’autres vestiges dans l’axe de l’escalier et de la pagode. Tous les édifices son en pierre de Bien-hoa, à l’exception de deux tours et de quelques portes et couronnements en grès, et de trois tours en brique. Ces ruines ont été portées à ma connaissance par l’intermédiaired’un missionnaire et d’un négociant francais, et alors elles ont été explorées par M. Aymonier [E. Aymonier, Géographie du Cambodge, p. 41 et suiv. E. Leroux. Paris, 1876], puis par moi. J’y ai conduit ensuite et successivement MM. Pierre, Regnault de Presménil et Spooner.”

“Khet Bati [province included in the great division of Treang] takes its name from a lake that the Cambodians call the lake of a beautiful place, tonlé Bati. It contains ruins that we explored in April 1874. Near the lake, a temple of the type of that of Phnom Bachey, and, as in front of this sanctuary, an isolated stone bearing a votive inscription of 1496 of the era of Buddha, that is to say 953 of J.-C., 8 years after that of Phnom Bachey. […] The very important sanctuary of Phnom Chiso, which was reached by a gigantic stairway of 380 steps, which must have connected the sanctuary to an inhabited center of which there remains a sala and other vestiges in the axis of the stairway and the pagoda. All the buildings are of Bien-hoa stone, with the exception of two towers and some doors and crowns in sandstone, and three towers in brick. These ruins were brought to my attention through a missionary and a French trader, and then they were explored by Mr. Aymonier [E. Aymonier, Géographie du Cambodge, p. 41 et seq. E. Leroux. Paris, 1876], then by me. I then took there successively Messrs. Pierre, Regnault de Presménil and Spooner.”

About this attempt to an etymology of បាទី Bati as “beautiful place”, we can only remark that បា ba refers to some fatherly or royal authority, and ទី ti has the meaning of ទ្រព្យជាទីស្រឡាញ់ beloved treasure. What was the status of this province in Ancient and Middle Cambodia? We’ll only note that these temples are dated to 12th or 13th century, and there is the case of the town called សៀមរាប Siem Reap, while ប្រាសាទតាព្រហ្ម Prasat Ta Prohm (Tonle Bati) has a famous eponym in Angkor Thom.

Exploring the temples of that province, the author did not find the manifestation of a central power, both political and religious, but rather an idiosyncrasic expression of Khmer syncretism:

Hors du chemin des invasions Siamoises et Annamites, les constructions qu’on rencontre dans cette province de Bâti ont moins souffert de la main des hommes, mais sont plus éprouvées par les injures du temps. C’étaient, sans doute, les premiers essais du peuple nouvellement converti. La munificence des souverains né semble guère s’être étendue jusqu’à ces frontières éloignées; la ferveur des adeptes dut seule contribuer, suivant les ressources de la localité et les moyens de chacun, à l’édification des premiers sanctuaires. La conception en est du reste semblable, car l’objet du culte était identique; mais l’inexpérience des débuts s’y trahit en maints endroits. Loin des bouleversements politiques et religieux de la capitale, cette contrée semble n’avoir reçu que tardivement le bouddhisme, et la tolérance chez les bonzes y va jusqu’à respecter ce qui reste des anciens usages, à honorer le lingam devant l’autel de Sakia-Muni et croire, tout comme les pauvres gens, aux Neac-tas de la forêt et à ceux de la montagne. Aussi, voit-on quelquefois réunies dans un meme sanctuaire les trois croyances successives des Khmers. [p 82, 84]

“Away from the path of Siamese and Annamite invasions, the buildings found in this province of Bâti have suffered less from the hands of men, but are more tested by the ravages of time. These were, without doubt, the first attempts of the newly converted people. The munificence of the sovereigns does not seem to have extended to these distant frontiers; the fervor of the followers alone must have contributed, according to the resources of the locality and the means of each, to the construction of the first sanctuaries. The design is moreover similar, because the object of the cult was identical; but the inexperience of the beginnings betrays itself in many places. Far from the political and religious upheavals of the capital, this region seems to have received Buddhism only late, and tolerance among the monks goes so far as to respect what remains of the ancient customs, to honor the lingam before the altar of Sakia-Muni and to believe, just like the poor people, in the Neac-tas of the forest and those of the mountain. Also, one sometimes sees the three successive beliefs of the Khmers united in the same sanctuary.” [p 82, 84]

Such a combination of beliefs is found at Phnom Chisor, where the author noted a form of stone cult:

Dans le bas côté nord du temple, sont remisées trois pierres en schiste noir, trouvées par les indigènes dans les

racines environnantes. Elles ont une face couverte d’inscriptions peu profondes, en vieux Khmer, et malheureusement nos empreintes prises avec du papier mouillé trop mince ont à peine retenu quelques traces des caractères.

“On the lower north side of the temple are stored three black schist stones, found by the natives in the surrounding roots. They have one face covered with shallow inscriptions in old Khmer, and unfortunately our prints taken with too thin wet paper have barely retained a few traces of the characters.” [p 93]

ADB Input: Four inscriptions, K 31, 32, 33 and 34 have been found at Phnom Chisor temple.

Le lac de Bâti est une sorte de cuvette peu profonde s’étendant de l’est à l’ouest dans une dépression du plateau sablonneux que forme cette province. Les rives sont boisées; et derrière ce rideau de verdure, on devine quelques villages indiqués par des bouquets de palmiers et la fumée grisâtre s’échappant de cases invisibles. C’est à peine si deux ou trois pirogues montées par des bonzes en quête de leur ration, ou par des pêcheurs, viennent animer le paysage. Il est six heures; à l’horizon, le soleil se couche derrière le Phnom-Sruoch [ស្រុកភ្នំស្រួច, about 70 kms west of Bati] dont il découpe vivement les sommets, tandis que vers l’est, on aperçoit au loin un déversoir naturel qui pendant la crue des pluies met le lac en communication avec le bras postérieur du grand fleuve. C’est au sud-ouest que se trouvent les ruines de Ta-Prom (ancêtre Brahma) et de Yeai-Pou (la vieille Pou) [ប្រាសាទយាយពៅ, with a modern pagoda right behind the tower]. Elles se composent d’un édicule, appelé Yeai Pou, situé à 50 mètres de la rive, et que les habitants d’une bonzerie assez importante ont aclopté comme sanctuaire d’un lingam (phallus) remarquable, auquel ils rendent leurs dévotions. Dans la forêt, à une centaine de mètres plus loin, est Ta Prom, l’édifice principal, envahi par la végétation, et par une légion de chauves-souris qui rendent l’accès de certaines parties à peu près impossible. Quelques jours avant notre arrivée, une tigresse avait élu domicile dans un édicule de la cour, mais comme elle eut l’impruclence de prélever la dîme sur les chiens cle la bonzerie pour nourrir sa progéniture, elle fut chassée par une grande battue et l’un de ses petits fut tué par un Cambodgien. [p 95]

Lake Bati is a sort of shallow basin extending from east to west in a depression of the sandy plateau that forms this province. The banks are wooded; and behind this curtain of greenery, one can make out a few villages indicated by clumps of palm trees and the grayish smoke escaping from invisible huts. It is barely if two or three pirogues manned by bonzes in search of their meal, or by fishermen, come to animate the landscape. It is six o’clock; On the horizon, the sun sets behind Phnom-Sruoch [ស្រុកភ្នំស្រួច, about 70 kms west of Bati] whose peaks it sharply outlines, while towards the east, one can see in the distance a natural spillway which during the flood of the rains puts the lake in communication with the posterior branch of the great river. It is to the southwest that one finds the ruins of Ta-Prom ប្រាសាទតាព្រហ្ម (ancestor Brahma) and Yeai-Pou (the old Pou) [ប្រាសាទយាយពៅ, with a modern pagoda right behind the tower]. They consist of a building, called Yeai Pou, located 50 meters from the shore, and which the inhabitants of a fairly large bonzerie have adopted as a sanctuary for a remarkable lingam (phallus), to which they render their devotions. In the forest, a hundred meters further, is Ta Prom, the main building, invaded by vegetation, and by a legion of bats which make access to certain parts almost impossible. A few days before our arrival, a tigress had taken up residence in a building in the courtyard, but as she was imprudent enough to take tithes from the bonzerie’s dogs to feed her offspring, she was chased away by a large pack and one of her cubs was killed by a Cambodian. [p 95]

Ta-Prom a bien conservé le nom et les traces de sa destination primitive : c’est bien un temple brahmanique, et

quoique modeste de proportions, naïf d’exécution, il a eu, grâce à cela peut-être, et aussi à son éloignement des grandes voies antiques, la bonne fortune de conserver une partie des divinités auxquelles il était dédié. Les frontons nord et sud, ainsi que ceux des édicules, sont intacts; seul, le fronton Est du sanctuaire a été martelé et grossièrement sculpté dans l’excavation d’un affreux buddha sommeillant à l’abri d’un parasol informe. Sous le dôme, on a également introduit un sakia efflanqué, haut de 2m50, debout, enseignant et protégé

contre toute main profane par un lac de guano infect qu’alimentent sans relache une nuée de chauve-souris

rousses. Il est impossible de pénétrer dans cet antre dègoûtant, qui d’ailleurs n’offre aucune particularité intéressante. C’est dans la galerie nord que sont relégués les dieux principaux, et rien né s’oppose à ce qu’on les examine à l’aise. Leur structure est plus que massive et leurs jambes surtout dénotent un parti pris d’éléphantiasis; ce sont des points d’appui qui soutiendraient le monde sans broncher : sauf les têtes, il me faut y rechercher aucun art. [p 98]

“Ta-Prom has well preserved the name and traces of its original destination: it is indeed a Brahmanic temple, and

although modest in proportions, naïve in execution, it has had, thanks to this perhaps and also to its distance from the great ancient roads, the good fortune to preserve a part of the divinities to which it was dedicated. The north and south pediments, as well as those of the aedicules, are intact; only the east pediment of the sanctuary has been hammered and crudely sculpted in the excavation of a hideous Buddha sleeping under a shapeless parasol. Under the dome, a gaunt sakia, 2.50m high, standing, teaching and protected from any profane hand by a lake of infected guano that is constantly fed by a cloud of red bats, has also been introduced. It is impossible to enter this disgusting lair, which moreover offers no interesting particularity. It is in the northern gallery that the principal gods are relegated, and nothing prevents one from examining them at ease. Their structure is more than massive and their legs especially denote a bias of elephantiasis; they are points of support which would support the world without flinching: except for the heads, one must look for no art there.” [p 98]

Many of the statues seen then in situ are now at the National Museum of Cambodia. And, after admiring the “remarkable” statue of a female deity — whose head had rolled over the ground nearby -, the author noted

Un trait remarquable de l’architecture khmer est la chasteté: on né trouve nulle part la représentation de ces scènes licencieuses qui ornent fréquemment les temples cle Crishna et que les Bouddhistes n’ont pas craint d’imiter en reproduisant les scènes du harem de Gopa et les tentations des filles de Mara. Ce que nous avons retrouvé de leurs divinités jusqu’à ce jour présente le même caractère, il est en outré remarquable par la la sérénité des poses et des expressions : là, point de faces grimaçantes, d’attitudes forcées et pleines de contorsions; les Khmers semblent enfin avoir compris la divinité majestueuse, quelles que fussent ses attributions. [p 100]

A remarkable feature of Khmer architecture is chastity: nowhere do we find the representation of those licentious scenes which frequently adorn the temples of Krishna and which the Buddhists did not fear to imitate by reproducing the scenes of the harem of Gopa and the temptations of the daughters of Mara. What we have found of their divinities up to this day presents the same character, it is further remarkable for the serenity of the poses and expressions: there, no grimacing faces, no forced attitudes full of contortions; the Khmers seem at last to have understood the majestic divinity, whatever its attributions. [p 100]

Photo: Prasat Ta Prohm Tonle Bati (photo MingLiang Travel)

Tags: Bati, archaeology, 1870s, French explorers, Khmer art, statues, Phnom Chisor, Tonle Bati

Andrew Spooner (1840, Paris — 29 July 1884, Cascade du Bois de Boulogne, Paris) was a French-American merchant established in Saigon [Ho Chi Minh Ville] in 1861, a reporter with French magazine L’Illustration who covered the French army’s assault on Bien-Hoa on 9 Dec. 1861, and an early Western explorer of Cambodia in November-December 1862.

With an American father (Andre-Andrew Spooner(1789-?), a chemical industrialist born in Boston (USA) on 30 Sept 1789, previously married to Charlotte Louis in 1823, Paris) and a French mother (Henriette Victorine Octavie Sebille-Descayes) he both hardly knew, as hew was raised by his eldest half-sister, Spooner apparently never visited the USA but held American citenzship all his life, and his guardian, a M. Courtin, encouraged him to leave for Singapore in 1859 in order to commercialize “Parisian items” such as lace on behalf of Maison Edouard Renard et Cie.

At 21, he had already spent two years in Singapore when he started his activities in French Indochina. He tried his hand in “several commercial ventures, from agriculture (an unsuccessful indigo plantation in 1869) to transport (a bimonthly steamboat service between Saigon and Phnom Penh in 1870) to the provision of urban amenities (gas lighting for Saigon). In the 1870s and early 1880s, he was a partner in a French-operated steam-driven rice mill, one of the few non-Chinese rice mills in Saigon [Rizeries de Cholon, launched with Renard & Cie in 1869].” [see “Rapport sur le Cambodge. Voyage de Sai-Gon à Bat-tam-bang/“Report on Cambodia. A Trip from Saigon to Battambang”, transl. by Nola Cooke, Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 南方華裔研究雜誌 , Vol. 1, 2007, p 154 – 169].

Mandated to manage the “ferme de l’opium” (opium tax management, which at some point made 25% of the French administration income) from 1867 to 1882, when the institution of the “Douanes et Régies” by Governor Le Myre de Villiers in 1881, brought to an end the occult monopoly of Chinese congregations on opium and alcohol imports — in particular Chinese businessmen Wang Tai, Banhap and Lu Chan, also influential in Phnom Penh and who were his business partners, along with Edouard Cornu, an affairist from Bordeaux -, Spooner was a member of the ‘Conseil privé de la colonie’, a powerful colonial governing body in Cochinchina, and had the upper hand on raw opium distribution in Cambodia. In 1860, he had coined the phrase: “The Chinese are Europeans’ indispensable ennemies.”

In 1862, Spooner explored Cambodia in order to assess the topography and potential resources for the French Navy. His findings were published three years later in a study, “Renseignements topographiques, statistiques et commerciaux sur le Cambodge” [“Topographical, statistical and commercial information on Cambodia”], where he lauded the natural resources and the silk from the country, advocating for the establishment of European trading posts in Phnom Penh. He was working closely with Admiral Louis Bonard.

Back to France in 1882, he married Valentine Charlotte Camille Angamarre (1859−1946) in Paris on 27 November that year, and they had one daughter, Marguerite Adélaïde Spooner, born on 8 June 1884, six weeks before Spooner’s premature death.

Andrew Spooner authored the only known plan of Oudong Royal Palace, site of Cambodian royal power until King Norodom undertook the erection of the new Palace in Phnom Penh starting from 1866 [source: L’Illustration, 30 Jan. 1864 [n 1092]: 72.]

Photo: from family tree Marie Odile Martin Descrienne, Geneanet.