Routes maritimes et contacts culturels entre la Méditerranée et l'Asia | Maritime Routes and Mediterranean-Asian Cultural Swaps

by Ariane de Saxcé

How the Greeks made their own discovery of the monsoon trade winds.

- Publication

- in P. Leriche, éd., Arts et civilisations de l’Orient hellénisé, Paris : Picard, 2014

- Published

- 2014

- Author

- Ariane de Saxcé

- Pages

- 16

pdf 3.0 MB

The study demonstrates how, while empirically discovering the climatic phenomenon of the Indian Ocean’s ‘trade winds’, Greek navigators, often hailing from Greek colonies in Egypt, developed a) a better understanding of the size and orientation of the Indian continent; b) technical resources adapted to high-sea navigation; c) a more accurate views on the potential for inter-continental trade, with an emphasis on Indian “aroma” (spices) and precious gems.

The figure of Hippalus (Ancient Greek Iππαλος, French Hippale) is of course central in the study. Pliny the Elder, after the anonymous Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, credited Hippalus with discovering the direct route from the Red Sea to Tamilakam over the Indian Ocean, but not the phenomenon of the monsoon wind (the south-west wind)…which was also called Hippalus.

Many scholars have stressed the fact that Hippalus was the first “Westerner” to comprehend the north-south direction of India’s west coast, as previous Greek geographers had thought it stretched from west to east. The author states that the surname Hippalus probably stems from the adjective “ὕφαλος, “«caché sous les eaux de la mer », terme qui caractérise les vents qui font se soulever les flots. Il aurait été attribué par la tradition à un mythique pilote sachant utiliser le vent de mousson, désigné sous le nom d’ Hippale. Il n’en reste pas moins que l’idée d’une initiation de certains marins égyptiens par des navigateurs indiens à la fin du IIe siècle av. n. è. [“avant notre ere” in French, meaning BC] constitue un deuxième critère de compréhension de la façon dont les Grecs d’Égypte ont pu s’approprier l’usage de la route maritime directe. La date la plus haute pour ce passage de relais nous est suggérée par Posidonius, à travers l’aventure du marin et marchand Eudoxe de Cyzique qui, à la fin du règne de Ptolémée VIII Évergète II Physcon (182−116 av. n. è.), est dit avoir appris d’un naufragé indien la navigation vers l’Inde, τὸν εἰς Ἰνδοὺς πλοῦν ἡγήσασθαι, et être revenu de cette première expédition avec des plantes aromatiques et des pierres précieuses, ἀρώματα καὶ λίθους πολυτελεῖς. Il n’est pas explicite si cette navigation emprunte la haute mer, mais certains éléments de la description invitent à cette interprétation, [comme] la nouveauté de cette route pour le personnage et la nature des biens rapportés, notamment les pierres précieuses.” [““hidden under the waters of the sea”, a term for the winds that cause the waves to rise. It would have been attributed by tradition to a legendary pilot who knew how to sail with the monsoon wind, designated by the name of Hippalus. Nevertheless, the idea of an initiation of certain Egyptian sailors by Indian navigators at the end of the 2nd century BC offers a second criterion to understand how the Greeks of Egypt were able to appropriate the use of the direct maritime route. The earliest date for this handover is suggested to us by Posidonius, through the adventure of the sailor and merchant Eudoxus of Cyzicus who, at the end of the reign of Ptolemy VIII Evergetes II Physcon (182−116 B.C.E.), is said to have learned from a shipwrecked Indian how to sail to India, τὸν εἰς Ἰνδοὺς πλοῦν ἡγήσασθαι, and to have returned from this first expedition with aromatic plants and precious stones, ἀρώματα καὶ λίθους πολυτελεῖς. It is not clear if this navigation takes the high seas, but certain elements of the description invite this interpretation, [such as] the novelty of this route for the character and the nature of the goods brought back, in particular the precious stones.”]

Furthermore, the monsoon specificity induced among the Egyptian Greeks a new navigation technique, and here again a little bit of philology appears handy: the verb τραχηλίζειν, explains the author, means literally “« renverser la tête [τράχηλος : le cou] en arrière » : dans ce contexte, il s’agit donc de tourner la proue du navire vers l’arrière, c’est‑à dire de venir au vent, en rapprochant l’avant du navire de la direction d’où vient le vent, le résultat étant une allure vent travers. Dans ce cas précis, cela signifie orienter sa course davantage vers le sud-sud-ouest, direction d’oùprovient le vent de la mousson d’été. Les indications données correspondent donc particulièrement bien à la réalité des différentes traversées : vent travers sur la totalité du trajet pour la route de l’Inde du Sud ; vent arrière d’abord (le long des côtes de l’Arabie), puis vent largue ou travers en laissant la côte au loin, pour se diriger soit vers Barbarikon au nord, soit plus au sud vers Barygaza. Le Périple, guide pragmatique, témoigne des connaissances empiriques de l’auteur et de sa proximité avec les réalités du terrain. Pline, pour sa part, évoque ces trois mêmes routes dans une perspective moins technique et plus historienne, en les présentant comme s’étant succédé dans le temps : « Dans la suite, il apparut que le trajet le plus sûr allait du cap Syagros en Arabie à Patalé avec le favonius […]. L’âge suivant jugea plus courte et plus sûre la route allant du même cap au port indien de Zigerus […] Ce fut pendant longtemps la route suivie jusqu’à ce qu’un marchand en découvrît une plus courte et que l’appât du gain rapprochât l’Inde […]. Le mieux est de partir d’Ocelis ; de là, par vent hippale, on gagne en quarante jours le premier entrepôt de l’Inde, Muziris.».” [““turning the head [τράχηλος: the neck] backwards”: in this context, it is a matter of turning the bow of the ship backwards, that is to say coming upwind, bringing the bow of the vessel from the direction the wind is blowing, resulting in a crosswind course, in this case heading more south-southwest, which is the direction the monsoon wind is blowing from. Thus, these indications match perfectly with the real conditions of the different crossings: crosswind over the entire route for the route to South India; tailwind first (along the coast of Arabia), then the wind drops or crosses, leaving the coast in the distance, to head either towards Barbarikon in the north, or further south towards Barygaza. The Periplus, a purely pragmatic guide, testifies to the author’s empirical knowledge and his proximity to Pliny who,for his part, evokes these same three routes from a less technical perspective and more historic perspective, presenting them as having succeeded each other in time: “Later, it appeared that the safest route was from Cape Syagros in Arabia to Patale with the favonius […]. The following age deemed the route from the same cape to the Indian port of Zigerus shorter and safer […] This was for a long time the route followed until a merchant discovered a shorter one, and the greed would bring India closer […]. The best is to start from Ocelis; from there, by hypalis wind [monsoon wind], we reach in forty days the first warehouse of India, Muziris”.”]

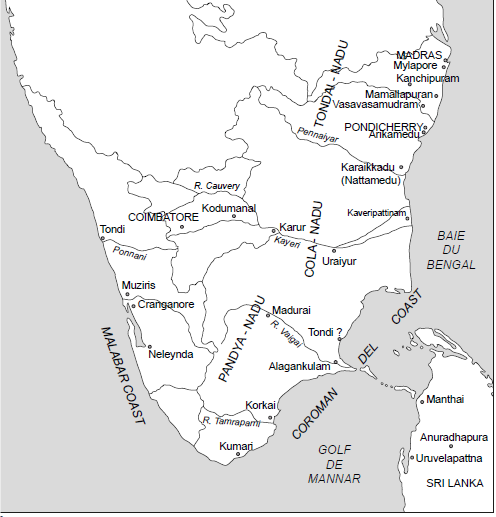

Main sites of South India — and part of Sri Lanka. (author’s map)

And thus, Hippalus’ direct route greatly contributed to propserous trade contacts between the Roman province of Aegyptus and India from the 1st century BCE. From Red Sea ports large ships crossed the Indian Ocean to the Tamil kingdoms of the Pandyas, Cholas, Tondais, and Cheras in present-day Kerala and Tamil Nadu. As the author remarks, the expansion of commercial and cultural exchanges added fluvial routes (Sri Lanka included) to the growing oceanic traffic: “L’usage de l’Indus comme voie commerciale apparaît également dans les preuves de contacts de l’Afghanistan tant avec l’Égypte qu’avec l’Inde et Sri Lanka. L’importation de lapis-lazuli à Anuradhapura et Tissamaharama indique des contacts avec la région du Badakshan en Afghanistan, dont cette pierre est issue, et l’information donnée par le Périple de l’exportation de lapis depuis le port de Barbarikon à l’embouchure de l’Indus permet de renforcer l’hypothèse de l’usage de l’Indus comme voie commerciale. Par ailleurs, les liens réguliers entre l’Asie centrale et Sri Lanka apparaissent dans la présence sur l’île d’une corporation de Kambojas, population d’Arachosie, et dans les monnaies bactriennes puis kouchanes mises au jour sur le territoire sri lankais, y compris sur la côte sud. Loin de se limiter à la côte ouest de l’Inde, le fleuve se révèle tout aussi important dans les liens avec l’Égypte, comme le suggère le « trésor » de Begram en Afghanistan, ville carrefour entre l’Inde, la Chine, l’Asie centrale, l’Égypte et Rome, ce dont témoigne la nature des vestiges mis au jour au sein de cet ensemble hors du commun.” [“The Indus River as a trade route also appears in the evidence of contacts from Afghanistan both with Egypt and with India and Sri Lanka. Imports of lapis lazuli to Anuradhapura and Tissamaharama indicate contacts with the region of Badakshan in Afghanistan, from which this stone comes, and the information given by the Periplus of lapis exports from the port of Barbarikon at the mouth of the Indus confirms the hypothesis of the use of the Indus as a trade route. Moreover, the regular links between Central Asia and Sri Lanka appear in the presence on the island of a corporation of Kambojas, a tribe of Arachosia, and in the Bactrian and Kushan coins unearthed in Sri Lankan territory, including on the southern coast. Far from being limited to the west coast of India, the river proves to be equally important in the links with Egypt, as the ” treasure” of Begram in Afghanistan, a city at the crossroads between India, China, Central Asia, Egypt and Rome, as evidenced by the nature of the remains unearthed within this extraordinary compound.”

- The author focused on ‘cultural appropriation in South Asia at the beginning of our era’ in a more recent study (‘Appropriations culturelles en Asie du Sud aux débuts de notre ère’, Histoire de l’Art, 2018).

- Main photo: Ancient Greece cargo ship (source AGFacts). Incidentally, the eyes painted on prows of both ancient Greek and Southeast Asian boats, do they belong to some ‘cultural appropriation’, and from whom to whom, or to the universal stock of human beliefs and superstitions?

Tags: maritime routes, Greek explorers, Ancient Greece, Roman Empire, India, Sri Lanka, monsoon, maritime trade, myths and legends

About the Author

Ariane de Saxcé

Ariane de Saxcé is an archaeologist and a Research Associate for South and Southeast Asia with Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI, Bonn, Germany) and University of Paris III Sorbonne.

Her specialization area is the archaeology of South Asia and the Indian Ocean, with an emphasis on maritime trade networks and cultural connections with the Mediterranean world. She has excavated in South India, Sri Lanka, Egypt and France, both on land and underwater. Her research relies on quantified analysis of archaeological remains, together with an anthropological approach of cultural artefacts, to put into relief the dynamics of the exchanges in this area and particularly the East to West flow of goods, people or iconography.