Maritime Trade between Thailand and Bengal

by Shahnaj Husne Jahan

A summary of archaeological finds shining a new light on the history of maritime trade and early Southeeast Asia.

- Publication

- วารสารวิจิตรศิลป์ ปีที่ 3 ฉบับที่ 2 กรกฎาคม - ธันวาคม 2555 | Journal of Fine Arts, Year 3, Issue 2, July - December 2012.

- Published

- 2012

- Author

- Shahnaj Husne Jahan

- Pages

- 24

- Language

- English

pdf 679.8 KB

The spread of Buddhism and the the expansion of maritime trade were deeply connected since early times, shows the author of this excellent summary combining archaeology and the history of material culture in India and Southeast Asia.

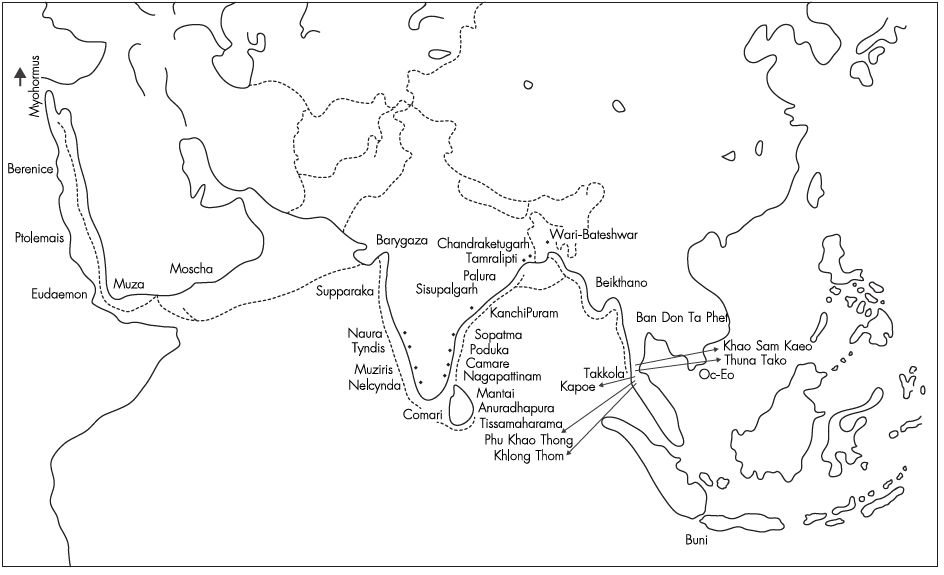

According to the author, “the distribution pattern of [these artefacts] is implying that the transshipment possibly took place along a coastal trade route (Sri Lanka-South India-Orissa-Bengal-Thailand). ‘Bengal’ lay midpoint between the western arm of the route (to south India and Sri Lanka) and the eastern arm (to Thailand and other regions of Southeast Asia). Primitive navigation and sailing schedule determined by monsoon winds, land and sea breeze would make sailing in this route feasible. It was single route two-ways, necessitating the use of the inter-monsoon period of August- September (for voyages to Bengal from Sri Lanka and South India) and the following inter-monsoon period from November to April (for voyages from ‘Bengal’ to Thailand).”

The author studies several examples of material culture archaeological finds that give us a better perception of regional trade at that time, amongst them:

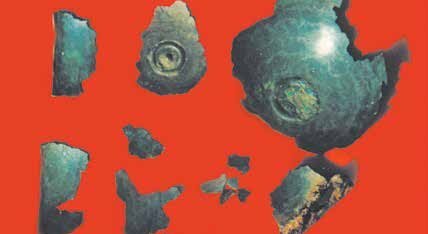

Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW, Ganga Plain clay)

“The distribution of NBPW from the period of 300 BCE to 100 BCE in South Asia is certainly widespread. This wide distribution has been ascribed to Mauryan imperialism, the propagation of Buddhism, and to trade routes because most of the South Asian sites that yielded NBPW were centres of Buddhism. The Indo-Aryan settlers in the Middle Ganga plains may have introduced this type of ware as their settlements gradually spread in the Lower Ganga plains along the banks of the Bhagirathi-Hugli during the Maurya rule. The chronology and distribution pattern of NBPW clearly indicates that these were exported from Ganga Valley to southeast Indian coastal sites, Sri Lanka and Thailand from the maritime port sites of Wari-Bateshwar in Bangladesh and Tamralipti (Tamluk in Medinipur district) and Gangabandar (identified with Chandraketugarh in 24 Parganas district) in West Bengal, India. The wide distribution of the ware suggests that it was included in a “typical inventory of trading goods”. Since most of the sites were centres of Buddhism, it is possible that Buddhist religious establishments were linked with the traders (who in this case were the Sreshtihs). Hence, “religious homogeneity of traders” is a definite possibility.”

Rouletted Ware

“Rouletted Ware is so called because a variety of forms including triangles, diamonds, parallelograms, wedges, and dots are ‘rouletted’ in a series of concentric grooves or incisions on the interior surface of the base. The pattern consists of one to three bands of concentric circles and each band is containing three to ten rows of closely placed indentations. It is characterized by thick incurved rims, a contiguous body and base.[…] XRD analysis performed by Vishwas D. Gogte show that “Rouletted Ware was produced at multiple production centres in the lower Ganga plain with the epicentre in the Chandraketugarh-Tamluk region of Bengal.”

Knobbed Ware

“Knobbed wares are so called because at the centre of the inner surface of the base stands a conical knob, which is circumscribed by a series of concentric grooves or incisions. The knobbed ware occurs in various fabrics such as earthen, bronze, high-tin bronze, granite and silver. Earthen knobbed ware has been found at Tham Sǔa in La Un district (Ranong province) and Khao Sam Kaeo in Muang district (Chumphon province) in Southern Thailand. Similar earthen vessels with knob have been reported from Wari-Bateshwar (Bangladesh), Harinarayanpur (West Bengal, India) and Sisupalgarh (Orissa, India). […] The concept of knobbed wares possibly spread through Buddhism from Ganga Valley to Thailand via the maritime port sites of Tamralipti (Tamluk) and Gangabandar (identified with Chandraketugarh) in West Bengal, India and Wari-Bateshwar in Bangladesh. The ware also demonstrates close proximity of Buddhism and trade guilds.”

Semi-Precious Stone Beads

“The archaeological sites of Thailand that yielded etched beads are at Ban Chiang, Ban Tung Ketchet, Kok Samrong, Lopburi, U Thong, Ban Don Ta Phet, and Khao Sam Kao. Because the technique of etching on stone beads was known only in South Asia, there can be little doubt that the Thai beads were imported from the above region. Bengal’s maritime contact with Thailand becomes a proven fact when Glover (1989, 17) points out that long and barrel-shaped agate beads with two rows of white zigzags in marginal bands have been found both at Chandraketugarh and Ban Don Phet. Hence, one can confidently include etched beads in a typical inventory of goods, which were traded between Bengal and Thailand.”

This map proposed by the author shows that, far from “crossing the Gulf of Bengal”, early maritime traders stayed close to the coastal line, and circumnavigated around Sri Lanka.

Photo: fragments of NBPW (by the author).

Tags: ceramics, Indian traders, Buddhism, Sri Lanka, Early India, Thailand, Gulf of Bengal, Bengal, maritime trade, material culture

About the Author

Shahnaj Husne Jahan

Dr. Shahnaj Husne Jahan Leena is an archaeologist, a professor and director at the Center for Archaeological Studies, University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh, specializing in the field of art history, culture and archaeology of South and Southeast Asia.

With a MA in Islamic Art & Archaeology from the Department of Islamic History & Culture, University of Dhaka (1991), and a PhD in Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology in Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute, Pune, India (1997), she is the author of Excavating Waves and Winds of (Ex)change: A Study of Maritime Trade in Early Bengal, and editor of Abhijñan: Studies in South Asian Archaeology and Art History of Artefacts.

A consultant to the Liberation War Museum, Agargaon, Dhaka, Dr. Shahnaj H. Jahan has also worked and published about South and Southeast Asian history, culture and archaeology, maritime archaeology, museology, cultural heritage management and community based sustainable heritage tourism, and traveled extensively in South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Central Asia, North America, England and Europe to carry out archaeological research, study museum collections, deliver lectures in the seminars and conferences.