Punyodaya (Na-T'i), un propagateur du tantrisme en Chine et au Cambodge a l'epoque de Hiuan-Tsang [Spreading Tantrism in China and Cambodia in the 7th century]

by Li-Kouang Lin

How a scholar and translator from India at the Chinese Tang court went twice to Chenla to spread the Tantric-Buddhist faith and collect "divine medicine".

- Publication

- Journal Asiatique, T 127, July-Sept 1935, pp 83-100 | gallica.bnf.fr, ADB editing.

- Published

- July 1935

- Author

- Li-Kouang Lin

- Pages

- 18

- Languages

- French, Chinese

pdf 980.9 KB

Was he a ‘Tang Emperor emissary’ to Chenla, or a roving monk versed in Tantric esoterism who went as far as Central Asian Pamyr and Java, or both? What were the “miraculous medicinal herbs” he brought back to the ailing emperor? Who were the “Chenla [Tantric] masters” who valued his teaching so much that they invited him to come back to what is now Cambodia in 663 CE?

The enigma starts with his name, and it is one of the author’s merits to clarify: the traveling sage who has come to be known as Punyopaya in modern Buddhist tradition was Punyodaya [ पुण्योदय: from puṇya+udaya, the rise of good fortune (resulting from virtuous acts done in a former life) ]. As early as in 1935, the author noticed that “Punyopana” was a transcription error made during the Song, Yuan and Ming periods, and perpetuaded in Nanjo’s catalogue.

In Ernest J. Eitel’s Hand-Book of Chinese-Buddhism being a Sanskrit-Chinese Dictiomary with Vocabularies of Buddhist Terms in Pali, Singhalese, Siamese, Burmese, Tibetan, Mongolian and Japanese (London, 2nd edition, 1888), we read:

NADI 屠 查 or Punyopaya 布加 局 伐 于 explained by ? 淮 , lit. progeny of happiness, Sramana of Central India who brought (A. D. 655) over 1,500 texts of the Mahayana and Hinayana Schools to China, fetched medicines (A.D. 656) from Kwanlun, and translated (A.D. 663) three works.

Further on, when checking nowadays’ Patriarch Minh Dang Quang Buddhist Dictionary (Tổ Đình Minh Đăng Quang PHẬT HỌC TỪ ĐIỂN), we read:

Bố Như Điểu Phạt Da: Punyopaya (skt) — Na Đề — Nadi (skt) — Một vị sư miền Trung Ấn, được kể lại như là vị đã mang sang Trung Hoa 1.500 kinh sách Đại và Tiểu Thừa vào khoảng năm 655 sau Tây Lịch. Đến năm 656 ông được gửi sang đảo Côn Lôn trong biển Nam Hải (có lẽ là Côn Sơn của Việt Nam) để tìm một loại thuốc lạ — A monk of central India, said to have brought over 1,500 texts of the Mahayana and Hinayana schools to China 655 AD. In 656 AD he was sent to Pulo Condore Island in the China Sea for some strange medicine.

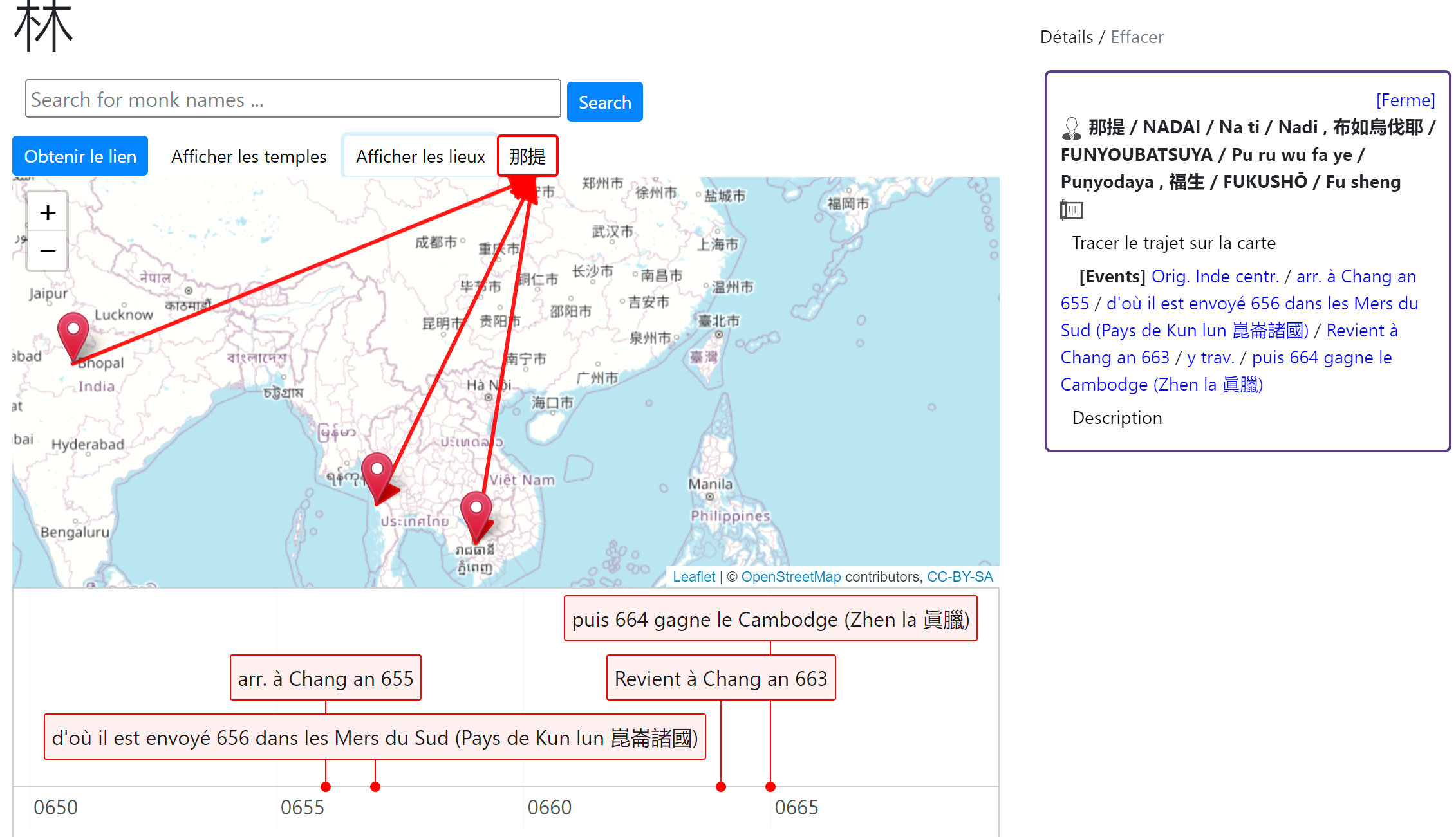

But when checking the Hobogirin digital map, we find the complete identity (Sanskrit, Chinese transliteration of Sanskrit, abbreviation of the latter, and Chinese name):

那提 / Nadai / Na ti / Nadi , 布如烏伐耶 / Funyoubatsuya / Pu ru wu fa ye / Puṇyodaya , 福生 / Fukusho / Fukusho sheng

Back to the present study, now. And before bringing in the necessary background, let’s meet this fascinating monk:

“Comme Subakharasimha et Vajrabodhi, Punyodaya (Na-t’i) était originaire de l’Inde Centrale, et comme Vajrabodhi et Amoghavajra, il voyagea à Ceylan, qui était alors un des centres du tantrisme indien. Comme Tche-t’ong, Bhagavaddharma et Atigupta, il représenle en Chine, au début des Tang, le tout nouveau mouvement tantrique. Il arriva à Tch’ang-ngan [Chang’an 長安, simplified Chinese, “Perpetual Peace”, now Xi’an, in North central China] en 655, avec une collection de manuscrits sanskrits aussi volumineuse, et contenant trois fois plus d’ouvrages, que celle que Hiuan-tsang avait rapportée en 645 […] Ce dernier se trouve assez clairement mis en cause pour son attitude à l’égard de Punyodaya, qu’il avait completement éclipsé à la cour. Bien reçu tout d’abord, logé et entretenu officiellement, Punyodaya se vit bientôt, un an après son arrivée, envoyé dans les “pays du Sud” (notamment au Cambodge), pour y “recueillir des herbes rares”, par l’empereur Kao-tsong qui le traitait ainsi comme un simple “employé”; peut-être Hiuan-tsang n’était-il pas étranger à cel éloignement d’un concurrent éventuel. Punyodaya vint “rendre compte de sa mission” à Tch’ang-ngan en 663, se proposant d’entreprendre alors la traduction de ses manuscrits sanskrits, et de réaliser ainsi le vrai but de sa venue en Extrême-Orient et de toute sa carrière. Mais ses manuscrits n’étaient plus à Tch’ang-ngan; Hiuan-tsang les avait emportés avec lui, quatre ans plus tôt, lorsqu’il avait quitté la capitale pour aller s’installer dans un palais en province! Avant de quitter définitivement la Chine où il n’avait passé en fait que deux années — en 664 pour retourner au Cambodge, Punyodaya réussit à traduire tout au moins trois petits textes, justement avec l’aide de Tao-siuan [Daoxuan, see below].

[“Like Subakharasimha and Vajrabodhi, Punyodaya (Na-t’i) was from Central India, and like Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, he traveled to Ceylon, which was then one of the centers of Indian tantrism. Like Tche-t’ong, Bhagavaddhama and Atigupta, he represented in China, at the beginning of the Tang, the brand new tantric movement. He arrived in Ch’ang-ngan [Chang’an 長安, simplified Chinese, “Perpetual Peace”, now Xi’an, in North central China] in 655, with a collection of Sanskrit manuscripts as voluminous, and containing three times more works, than that which Hiuan-tsang [Xuanzang, see below] had brought back in 645 […] The latter finds himself quite clearly questioned for his attitude to the with regard to Punyodaya, whom he had completely eclipsed at court. Well received at first, officially housed and maintained, Punyodaya soon found himself, a year after his arrival, sent to the “southern countries” (notably Cambodia), to “collect rare herbs”, by the emperor Kao-tsong who treated him like a mere “employee”; perhaps Hiuan-tsang was not unconnected with this distance from a possible competitor. Punyodaya came to “report his mission” to Ch’ang-ngan in 663, intending to undertake the translation of his Sanskrit manuscripts, and thus to realize the true purpose of his coming to the Far East and of his entire career. . But his manuscripts were no longer in Tch’ang-ngan; Hiuan-tsang had taken them with him four years earlier when he left the capital to settle in a palace in the provinces! Before leaving China definitively where he had only spent two years — in 664 to return to Cambodia, Punyodaya managed to translate at least three small texts, precisely with the help of Tao-siuan” [Daoxuan, see below].

Quoting directly from the Xu kao-tseng zhuan [1] , the author then adds the following biographical elements:

“Instruit par des maitres celebres, il conçut le désir de propager le bouddhisme. Il voyagea successivement dans tous les pays, afin d’instruire les hommes. Il était versé dans la grammaire et excellait dans l’explication des textes. […] Il aimait tout le monde et avait le gout des choses curieuses. Quand il entendait parler de quelque chose qui puisse aider à comprendre la doctrine, il né craignait jamais d’aller [s’en enquérir] même au loin chez les étrangers. […] Naguere il se rendit à Ceylan et fit l’ascension, au Sud-Est, du mont Lanka [2]. Et suivant les occasions il enseigna et convertit les gens des pays des Mers du Sud. Il était habile à apprendre les écritures et les langues. Il convertissait les hommes et fondait des établissements religieux. Il enseignait partout où il allait […]. Cette année-là (663), les gens du pays de Tchenla (Cambodge), dans les Mers du Sud, ou Na-t’i avait déjà propagé la religion, et qui n’avaient cessé de le respecter, voulurent le revoir. Les grands maîtres de tout l’ensemble de ce pays s’en vinrent au loin pour l’inviter, disant qu’il y avait chez eux de bonnes herbes médicinales connues de Na-t’i seul, et le priant de venir les recueillir lui-meme. Un édit impérial l’autorisa à s’y rendre. Et [désormais] son retour né fut plus possible. J’ai interrogé un [ou des voyageur(s] du Ta-hia ( Tokharestan), qui m’a [ou m’ont] dit que le maitre du Tripitaka Na-t’i était un disciple de Nagajuna. [La doctrine du] Nirlaksana, qui était la sienne, était fort différente de celle de Hiuan-tsang. Des moines de l’Inde (Tientchou) disent que depuis la mort du grand maitre (Nagarjuna) cet homme fut le premier pour la connaissance profonde du vrai Laksana et des procédés salvifiques (upaya) […] Na-t’i était venu [en Chine] avec la doctrine; s’il avait été placé dans une situation à sa taille, il aurait fait les preuves de son indépendance. Mais il subit du tort à plusieurs reprises, puis fut chargé d’une mission dans le Sud. Il parcourut plusieurs myriades [de li] par chemins montagneux, et brava à plusieurs reprises l’air malsain [des Tropiques]. Et c’est là qu’il dut sacrifier sa vie. Hélas! que c’est regrettable!”.

[“Taught by famous masters, he conceived the desire to propagate Buddhism. He traveled successively to all countries, in order to instruct men. He was versed in grammar and excelled in the explanation of texts. […] ] He loved everyone and had a taste for curious things. When he heard of something that could help to understand the doctrine, he never feared to go [to inquire about it] even far away among strangers. [ …] Formerly he went to Ceylon and climbed Mount Lanka. [2] And as opportunities were given to him he taught and converted the people of the South Sea countries. He was skilled in learning scriptures and languages. He converted men and founded religious establishments. He taught wherever he went […]. That year (663), the people of the country of Tchenla (Cambodia), in the Seas of South, where Na-t’i had already propagated the religion, and who had never ceased to respect him, wanted to see him again. The great masters of all of this country came far away to invite him, saying that there were good medicinal herbs among them known only to Na-t’i, and begging him to come and collect them himself. An imperial edict authorized him to go there. And [henceforth] his return was no longer possible. I questioned one [or traveler(s] from Ta-hia (Tokharestan), who told me [or told me] that the master of Tripitaka Na-t’i was a disciple of Nagarjuna. [The doctrine of] Nirlaksana, which was his, was very different from that of Hiuan-tsang. Monks from India (Tientchou) say that since the death of the great master (Nagarjuna) this man was the first in the deep knowledge of the true Laksana and the salvific processes (upaya) […] Na-t’i had come [to China] with the doctrine; had he been situated in a position suitable to him, he would have demonstrated his independence. But he was vexed several times, and then was sent on a mission to the South. He traveled several myriads [of li] by mountainous paths, and repeatedly braved the unhealthy air [of the Tropics]. And that’s where he had to sacrifice his life. Alas! How regrettable!”

Healing the Emperor: ailments and the quest for immortality

As reported in the study, Punyodaya was sent to the “South Sea countries”, and in particular Chenla, no less than twice. And he seems to have died there, but we do not know how and why. His stays in Chenla occurred when King Jayavarman I ជ័យវរ្ម័នទី១ was reigning over a divided country (around 657 – 681). China was then ruled by Gaozong of Tang (21 July 628 – 27 Dec 683), personal name Li Zhi, the third emperor of the Chinese Tang dynasty, who in theory reigned from 649 to 683 but, precisely after January 665, handed imperial power to his second wife Empress Wu (the future Wu Zetian), as his health was worsening.

In a 2019 unsigned study published on 小石娱乐君 (Xiaoshi Entertainment) blog, 古代皇帝都追求寻仙问道之术?(Did all ancient emperors pursue the art of seeking immortality?), we read that

As late as October of the fifth year of Xianqing (660), Emperor Gaozong began to suffer from the symptoms of “wind-dazzled head, heavy head, and blindness”. This condition is obviously related to his family inheritance, because his biological mother, the eldest grandson, the Queen, died of severe “qi disease”, and his father Taizong also suffered from “qi disease”, which later turned into “wind disease”, and even his grandfather Emperor Gaozu also died of “wind disease”. […] As early as more than ten years before this, Emperor Gaozong began to send people to India and various places in the South China Sea to seek medical treatment and medicine, and there were more than one group of people. During the Linde period (664−65), the monk Xuan Zhao was ordered to go to India to fetch the long-time Brahmin Lu Jia Yi Duo.

Obviously, this was another group of envoys sent by Gaozong, who had already arrived to visit Lu Jiayiduo first. In fact, as early as the first year of Xianqing (656), Emperor Gaozong sent the Central Indian monk Nati (Sanskrit name “Buruwuvaxie”, Sanskrit Punyopaya “Fusheng”) to the Kunlun countries in the South China Sea to “find exotic medicines” “, and he returned to Chang’an in the third year of his reign (663). At that time, he was also ordered to go to Zhenla Kingdom in the South China Sea to collect medicine. The end title of the Dunhuang document “Buddha Speaks of the Great Dealing with Evil and the True Sutra” reads: “Xuan Fu, senior masters, Xie She and others found a volume of the Tathagata’s Great Addiction, Evil and Righteousness, the Deep Secret Sutra in the Tathagata’s Cave of Seven Treasures. It mentions “Long-term teacher”, the author speculates that it is Nati.

According to the “Sutra Translation Chapter·Biography of Sanskrit Monk Nati of Da Ci’en Temple in Beijing” in Volume 4 of “Continued Biography of Eminent Monks”: “Nati Sanzang was born in the Tang Dynasty. The Indian collected more than 500 Mahayana sutras and commentaries, combined them into more than 500 volumes, and arrived in the capital in the sixth year of Yonghui (655). There was an edict to Zheng’en arranged the place and provided the supplies. Master Xuanfu was translating on the way, and his voice was booming. … He revealed all the sutras and pretended to go north. … Nati Tripitaka is a disciple of Nagarjuna.

Nagarjuna is a famous person in India who is proficient in the art of immortality. Xuanfan said in Volume 10 of “Records of the Western Regions of the Tang Dynasty”: “Longmeng Bodhisattva is good at leisure medicine and uses food to maintain health. He can live for hundreds of years and has unfailing ambition. Four Dragon Meng (Nagarjuna in Sanskrit), also known as Nagarjuna, is the founder of the Madhyamaka sect of Mahayana Buddhism in India. He was active around the end of the 2nd century and the beginning of the 3rd century. Legend has it that he is good at medicine and can live forever. His disciples are called “Nagarjuna” and are known for their longevity.

According to Volume 29 of Zhipan’s “Chronicles of the Buddha”: “The master (Xuanzang) came to Tianzhu and met the Nagarjuna Sect. He wanted to follow his disciples’ instructions to take medicine for longevity, and then he could study the purpose thoroughly. The master thought to himself, this is He wanted to seek sutras, but he was afraid that he would not be able to achieve his long-cherished wish because of his failure to achieve immortality. So he studied Dharma with Jie Xian and taught him the Knowledge-only Sect doctrine.

Indian medical books translated during the Sui and Tang Dynasties were often written by Nagarjuna. Since Nati was a member of Nagarjuna’s sect, he should naturally be proficient in the art of immortality. In addition, when Nati brought a large number of scriptures to the Tang Dynasty, he happened to be placed in the translation room of the Xuanfu Organization in Da Ci’en Temple. From this point of view, the “Master of Immortality” listed with Xuanzang at the end of “The Classic of Dialectics of Evil” should be No doubt about that. It is precisely in the first year of Xianqing (656) that Gaozong sent the Indian monk Nati to seek exotic medicine as the background. This makes it easy to understand why Wang Xuance would recommend Naluo Saha to Gaozong again the following year. Although Gaozong rejected this matter, it is an indisputable fact that he always paid more attention to taking food and maintaining health.

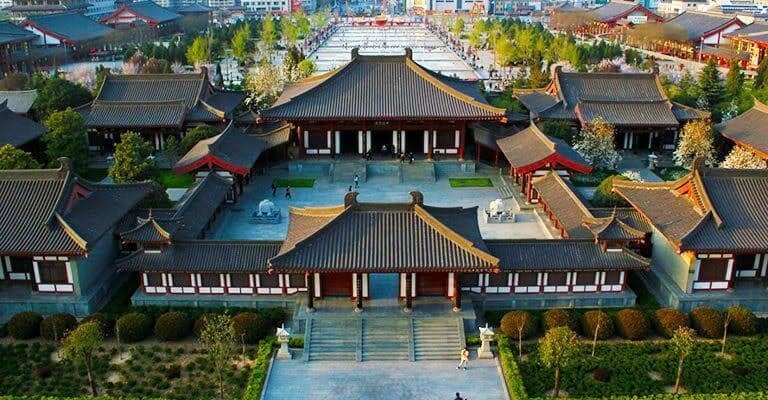

Daci’en Temple 大慈恩寺 is a Buddhist temple located in Yanta District, Xi’an [formerly Chang’an] erected in 648 by Prince Li Zhi, the later Emperor Gaozong of Tang, in commemoration of his mother Empress Zhangsun The Giant Wild Goose Pagoda was then ran by the monk Xuanzang, and alongside Daxingshan Temple and Jianfu Temple, was one of the three sutras translation sites (三大译经场) in the Tang dynasty. (photo TheGreatPatronofBuddhism, 2019)

Punyodaya, an Indian monk amongst his Chinese counterparts

The records mentioned in this essay reflect the mixed feelings Punyodaya inspired to Chinese Buddhist scholars, from blatant hostility in the case of Xuanzang to admiration from Daoxuan, to emulation from Yijing.

Xuanzang 玄奘 (6 Apr 602, Chenliu, Henan Province, China – 5 Feb 664, Chang’an), born Chen Hui 陳禕), Sanskrit Dharma name Mokṣadeva, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator who travelled through China and India in search of the sacred books of Buddhism.

Ignoring the ban on traveling abroad, at age 27 he began his seventeen-year overland journey to India, visiting among other places the Nalanda monastery in modern day Bihar, and returning with some 657 Sanskrit texts on a caravan of twenty packhorses. He was welcomed back by Emperor Taizong, who encouraged him to write down his travelogue, titled The Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, a text that inspired nine centuries later the novel Journey to the West to Wu Cheng.

The Baidu Encyclopedia entry for Punyopanya [thanks to Pascal Medeville for pointing us to it] states that “he was ostracized by Xuanzang because he and Xuanzang disagreed on the concept of animitta 无相. He returned home in despair and died of miasma on the way.” According to the Wisdom Library Maha Prajnaparamita Sastra,

“Ānimitta (आनिमित्त, “signlessness”) or Ānimittasamādhi refers to a type of Samādhi [‘fixity of the mind’, ‘ecstatic meditation’], representing a set of “three concentrations” acquired by the Bodhisattvas, according to the 2nd century Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra chapter X. a) Some say: Ānimitta has for its object the Dharma free of the following ten marks: a) the five dusts (rajas, namely, color, sound, smell, taste and touch); b) male and female; c) arising (utpāda), continuance (sthiti), cessation (bhaṅga). b) Others say: All dharmas are free of marks (animitta). Not accepting them, not adhering to them is ānimitta-samādhi. c) Furthermore: ānimitta-samādhi is suppressing all the marks of the Dharmas (sarvadharma-nimitta) and not paying attention to them (amanasikāra).”

Daoxuan 道宣 (596 – 667 CE) was an eminent Tang dynasty Chinese Buddhist monk, patriarch of the four-part Vinaya school (四分律宗), and author of Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (Xù gāosēng zhuàn 續高僧傳), Standard Design for Buddhist Temple Construction, Five Great Works of Mount Zhongnan, and the Nèidiǎn Catalog. Part of the translation team that assisted Xuanzang in translating sutras from Sanskrit into Chinese, he worked closely with Punyodaya and did not shy away from criticizing Emperor Gaozong attempted edicting which pretended to require that monastics bow before him.

Yijing 義淨 (635 – 713 CE), born Zhang Wenming, was a Tang-era Chinese Buddhist monk, traveler and translator, who sailed to India in 673 out of Guangzhou, stopping for six months in Srivijaya (today’s Palembang, Sumatra) in order to learn Sanskrit grammar and the Malay language. After studying at the University of Nālandā, he stopped again in Srivijaya on his way back to Tang China in 687. In 695, after completing his massive translation work of Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures into Chinese, he returned to China, bringing back some 400 Buddhist texts from the Sanskrit canon and being warmly greeted by Empress Wu Zetian. His travel diaries include The Account of Buddhism sent from the South Seas and Buddhist Monk’s Pilgrimage of the Tang Dynasty.

Personal rivalry and/or religious divergence may be at the core of the “unfair” treatment Punyodaya suffered in China. It is interesting to note how ‘Nati Tripitaka’ is perceived in Chinese modern popular history. For instance in this 2021 blog post:

那提三藏:梵名布如烏伐邪(Punyopaya),此言福生,後訛略而稱那提。中印度人,嘗往執師子國(今斯里蘭卡),登棱伽(Lanka)山。「承脂那東國,盛轉大乘,佛法崇盛,贍洲稱最。乃搜集大小乘經律論五百餘夾,合一千五百餘部,以永徽六年(655年)創達京師,在敕令於慈恩寺安置」,旋於顯慶元年(656年)敕往崑崙諸國採取異藥。既至南海,諸王歸敬,為別立寺,度人授法。龍朔三年(663年)返歸慈恩寺,同年因真臘國請,下敕聽往,返跡末由。那提三藏係印度高僧中遵海路東來的重要人物,其學識至為淵博,惜因所奉教派與玄奘不同而受排斥。故《續高僧傳》作者為之不平而云:「夫以抱麟之歎,代有斯蹤,知人難哉,千齡罕遇。……委命遭命,斯人斯在,嗚呼惜哉! [Nati Sanzang: The Sanskrit name is Punyopaya. This is said to be blessed, and later it was incorrectly called Nati. The monk from Central India went to the country of Jushizi (now Sri Lanka) and climbed Mount Lanka. “In the Eastern Kingdom of Chengzhi, Mahayana flourished, Buddhism flourished, and Fanzhou was the most prosperous. He collected more than 500 bundles of Mahayana and Hinayana sutras, combined them into more than 1,500 volumes, and created them in the sixth year of Yonghui (655). He arrived at the capital and ordered to settle it in Da Ci’en Temple. In the first year of Xianqing (656), he was ordered to go to the Kunlun countries to collect exotic medicines. When they arrived at the South China Sea, all the kings paid their respects and built separate temples to teach people the Dharma. In the third year of Longshuo (663), he returned to Ci’en Temple. In the same year, he was invited by Zhenla Kingdom and issued an edict to listen to it, but he did not return to the temple. Nati Tripitaka was an important figure among the eminent Indian monks who came east from Zunhai Road. His knowledge was extremely profound, but he was ostracized because his sect was different from that of Xuanzang. Therefore, the author of “The Continuing Biography of Eminent Monks” said because of this unfairness: “I sigh at Baolin, there is such a trace in the past, it is difficult to know someone, and it is rare to meet someone in a thousand years. … I was entrusted with fate, and this person is here, so sorry!]

[1] Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (Xù gāosēng zhuàn 續高僧傳), compiled by Daoxuan (Tao-siuan) right after Punyodaya’s departure from China, between 664 (interestingly, the year Xuangzang died) and 667, when himself passed away. The title refers to the earlier Gaoseng chuan 高僧傳 [Kao-seng chuan] “Biographies of eminent monks” (14 fascicles), compiled by Huìjiǎo 慧皎 18th year of Tianjian 天監 Liang dynasty 梁 (519 CE) in Jiaxiang Monastery (嘉祥寺).

[2] In Sri Pada, Buddhism Most Sacred Mountain by the Venerable S. Dhammika, we read that “the Indian monk Punyopaya “climbed Mount Lanka” while on his way to China in 655. At about the same time the Kashmiri monk Vajrabodhi visited Sri Lanka and after a six month stay in Anuradapura, set out for Sri Pada. “When at last he reached the foot of the mountain, he found the country wild, inhabited by wild beasts and extraordinary rich in precious stones.” Like many pilgrims Vajrabodhi was moved by the spectacular view from the mountain’s top. “After long waiting, he was able to climb to the summit and contemplate the impression of the Buddha’s foot. From the top he saw to the north west the kingdom of Ceylon and on the other side the ocean”. In 1411 the grand fleet of the emperor of China commanded by the eunuch admiral Ch’ing-ho, arrived in Galle harbour to offer gifts to the sacred footprint on the emperor behalf. According to the inscription Ch’ing-ho later set up to record his mission, the gifts included ” 1000 pieces of gold, 5000 pieces of silver, 50 rolls of embroided multicolored silk, 4 pairs of jewelled banners, 5 antique incense burners, 6 pairs of gold lotuses, 2,5000 catties of perfumed oil” and numerous other things. In 1423 a large group of Thai and Cambodian monks who were in Sri Lanka studying and collecting texts climbed the sacred mountain before returning to their homelands. The leader of this group made a copy of the footprint and took back to Thailand with him. At the beginning of the 16th century the Portuguese conquered Sri Lanka’s maritime provinces and forbade Buddhists living under their jurisdiction and those coming from overseas from going to Sri Pada. […] The first western reference to Sri Pada is in Ptolemy’s Geography where it is called Valspada and the first specifically Christian mention of it is found in Valentinus’ Pistis Sophia. In this 2nd century Gnostic work Jesus is represented as saying to the Virgin Mary that he had appointed the angel Kalapataras as guardian over the mark “impressed by the foot of Adam and placed him in charge of the books of Adam written by Enoch in Paradise”.

Tags: tantrism, Indian travelers, Buddhism, China, Chinese Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism, Chenla, Jayavarman I, medicine, medicinal herbs, healing

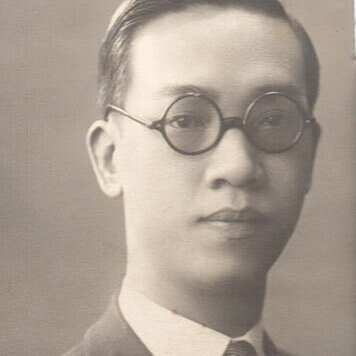

About the Author

Li-Kouang Lin

Lin Li-kouang 林藜光 (1902, Xiamen (Amoy), Fujian Province, China – 29 Apr 1945, St Hilaire du Touvet, Isere, France) was a Buddhologist researcher who worked in France with the most distinguished Sanskritists, Sinologists and Indologists, including Paul Demiéville (1894−1979) when he was based in Xiamen, Alexander von Staël-Holstein (1877 – 1937), Louis Renou and Sylvain Lévi (1863−1935), who taught him Sanskrit and Pali at the College de France.

In 1933, Lin Li-kouang was invited to come to France and work as Chinese assistant to Paul Demiéville, professor at INALCO (School of Oriental Languages). He had already started to compile the Chinese-Sanskrit Index of Kāśyapaparivarta that comprised more than 10, 000 entries, a work that was never published. His wife, Li Wei, was a young poetess and calligrapher.

Under the mentorship of Louis Renou (1896 – 1966), then the director of the fourth section of the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Lin Li-kouang finalized the edition of the 2,549 Dharma-samuccaya stanzas, accompanied by annotations, from a manuscript found by Lévi in Nepal in 1922. The Sanskrit text was published with the revised and corrected Tibetan translation and Chinese translations, as well as a French translation that Lin Li-kouang did himself.

According to Tianzhu Buddist Network, “the suffering of the war years, the overwork and his anguish towards the sad fate of his distant county and his relatives, took a toll on his health. On April 29, 1945, at dawn, he died silently and in absolute solitude at the sanatorium of St-Hilaire-du-Touvet (Isère) at the age of 43. The following year, his remains were transferred to the Père-Lachaise Cemetery where he is now resting for eternity.”

According to his son, Lin Xi, Lin Li-kouang was an ardent supporter of the anti-Nazi Resistance, and prayed for the end of the Japanese occupation of China during World War II (See ‘Hommage to Lin Li-kouang (1902−1945)’, Supplement to Études Chinoises vol 34 – 1, 2015).