Report of an Expedition Made into Southern Laos and Cambodia in the Early Part of the Year 1866

by H.G. Kennedy

'British spy' or first adventurous British tourist in Angkor? A young consular official's lively report of photographer John Thomson's journey.

- Publication

- The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 37 pp. 298-328 | Wiley with Institute of British Geographers

- Published

- 1867

- Author

- H.G. Kennedy

- Pages

- 31

- Language

- English

pdf 3.3 MB

Amongst the numerous interesting notations by the author during his Cambodian journey with John Thomson (whom he referred to as a “photographic artist”), we have selected:

- Siemreap as a Buddhist center in the 1860s: ‘Numerous temples of modern construction smround the city of Siemrap; but they lack the solidity which marks the earlier structures, and are already in an advanced stage of decay.There can be little doubt that this place was formerly one of the great centres of the Buddhist worship, and the number of priests to whom, even at the present day, it affords a maintenance, is strangely disproportionate to the extent of’ the population.’

- On Doudart de Lagrée being an earlier explorer at Angkor: ‘On the 4th of March, and while we were still quartered on the premises of Nakhon Wat, Captain de Lagree, Commander-in-Chief of the French forces in Cambodia, arrived on a visit to the ruins. He brought three French sailors and a draughtsman among his train, and took up his residence on the same ground as ourselves. I ascertained afterwards that this was the second time that Captain de Lagree had been in the neighbourhood.’

- Life and worship in Angkor Wat: ‘Our quarters during the chief part of our stay in the locality were in one of the numerous salahs, erected from time to time by merit-working visitors in the spacious enclosure which surrounds the great temple before mentioned, which the care of the architect who designed the whole has furnished with more than one reservoir of excellent water. About thirty or forty priests have fixed their habitations under the shelter of the ruins, and find a never-failing employment in conducting the obsequies of those whose bodies are brought to this highly-venerated sanctuary for cremation ; and when to the music and feasting, which forms part of such ceremonies, we add the constant influx of visitors who come to make offerings at the shrine, it will be seen that it was not in forest loneliness, but rather amid a busy scene of life, that we were established.’

- Kingdom of Cambodia population: ‘The King of Cambodia [King Norodom I] told me that the population in his dominions might be reckoned at a low estimate to comprise 100,000 Cambodians, 10,000 Cochin Chinese, and a multitude of Chinese settlers. He could furnish, he said, no precise information of the extent of his territory, nor of the number of days in which an elephant could cross it. I ascertained, however, subsequently, that it is made up of fifty-five towns.’

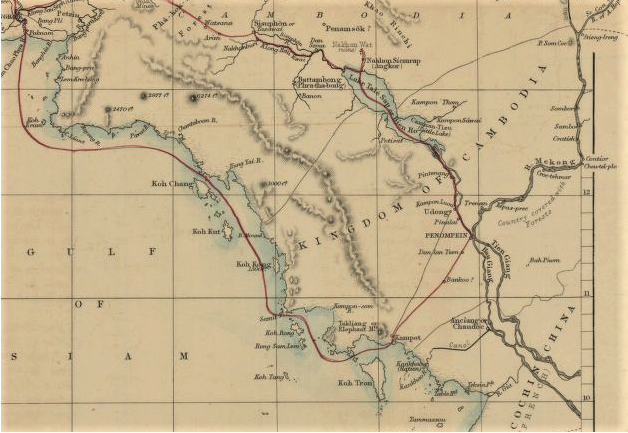

From Bangkok to Angkor, Phnom Penh, and Kampot by land, and return by sea.

Elephants and their minders at Angkor Wat (photo by John Thomson)

Tags: British explorers, photography, Tonle Sap, Udong, Khmer religion, early explorers

About the Author

H.G. Kennedy

Henri George Kennedy was a Student Interpreter at the British Consulate in Bangkok when he met pioneer photographer J. Thomson and went with him in his famous travel through Cambodia in January-May 1866.

Fluent in Thai (Siamese), H.G. Kennedy is credited to have saved Thomson’s life when the latter contracted high fever during the journey. While several French officials in Cambodia suspected him to be a British spy, it seems that Kennedy, then a young expatriate, was merely attracted by the adventurous travel.

However, Jim Mizerski noted in Cambodia Captured: “Given the unresolved political scenario in Southeast Asia at the time, it is not unlikely that Kennedy’s participation involved more than just accompanying Thomson. lt was an opportunity for Great Britain to get a good look at Angkor and a better assessment of the French in Cambodia while still maintaining the pretext of being little more than a tourist. Kennedy was likely collecting intelligence, but in plain sight and with deniability due to his authentic position as a junior interpreter. He later wrote a paper about the trip for the Royal Geographical Society of London that was accepted and published. His report to his superiors in Bangkok probably included more information than was included in the R.G.S.L. paper.”

The British mission in Bangkok had been established in 1856, in a building on Charoen Krung Road by the Chao Phraya River that became the UK Embassy in 1947, until its demolition for urban development in 2017.