Supply and Demand: exposing the illicit trade in Cambodian antiquities through a study of Sotheby's auction house

by Tess Davis

The dubious methods of international auction houses singled out by a respected observer of Ancient Khmer art market worldwide.

- Publication

- Crime, Law and Social Change (2011) 56:155-174

- Published

- 2011

- Author

- Tess Davis

- Pages

- 20

- DOI

- 10.1007/s10611-011-9321-6

- Language

- English

pdf 11.7 MB

This challenging study, published at a time looted art and museum restitution was not a trendy theme as it became later, makes quite powerfully the case for bringing some lawfulness and fairness to the international market of antiquities:

“Does it matter whether artifacts were blasted from temples by Khmer Rouge guerillas in the last decade, or chiseled away by French colonials in the last century? Both destroyed the history of many for the pleasure of a few. No one questions the lure of antiquities-archaeologists especially-but by purchasing them, especially absent a provenance, collectors are both condoning and even encouraging the destruction of the very art they love.”

Focusing on Cambodia, the author states that her study “demonstrates that the battle to protect the past is best fought in those countries where looted art is bought and sold. Cambodia’s own laws protecting its cultural heritage had little, if any effect, on the number of Khmer pieces entering the international art market. The U.S. import restrictions, however, seemed to have a huge impact. If other art market countries enact and enforce more such laws, then perhaps they will begin to stifle the demand for illicit Khmer art, eventually leading to a decrease in the looting of Cambodia’s archaeological sites. Such nonnative changes may seem overly optimistic, but they have happened in the past, most remarkably in response to campaigns against the wildlife trade.”

Sotheby’s, in particular, is the butt of her enquiry: “For over 20 years, its Department of Indian and Southeast Asian Art in New York City has held regular sales of Cambodian antiquities, which have been well published in print catalogues and on the web. These records indicate that Sotheby’s has placed 377 Khmer pieces on the block since 1988-when those auctions began-and 2010. An analysis of these sales presents two major findings. Seventy-one percent of the antiquities had no published provenance, or ownership history, meaning they could not be traced to previous collections, exhibitions, sales, or publications. Most of the provenances were weak, such as anonymous private collections, or even prior Sotheby’s sales. None established that any of the artifacts had entered the market legally, that is, that they initially came from archaeological excavations, colonial collections, or the Cambodian state and its institutions. While these statistics are alarming, in and of themselves, fluctuations in the sale of the unprovenanced pieces can also be linked to events that would affect the number of looted antiquities exiting Cambodia and entering the United States. This correlation suggests an illegal origin for much of the Khmer material put on the auction block by Sotheby’s.”

With the sharpness of a seasoned market analyst, the author notes that “in the late 1980s, when Sotheby’s began its regular sales of South and Southeast Asian art, ten or fewer unprovenanced Khmer artifacts were auctioned each year. This number quickly rose, nearly tripling after 1989, and remained strong until 1993. It then began to drop, until 1998, after which it again spiked Starting in 1999, however, it plummeted and has remained low ever since. In 2008 and 2009, Sotheby’s auctioned no unprovenanced Khiner objects, and in 2010 it auctioned only four. Table 2 illustrates these fluctuations, but what do they mean, if anything? It could be argued that they represent the changing demand for Khmer antiquities. According to this line of reasoning, when Sotheby’s first began its regular Indian and Southeast Asian Art auctions in 1988, demand for Khmer pieces was low, then grew throughout the early 1990s, due to Cambodia’s increasing newsworthiness. It eventually tapered off after the turn of the millennium, when the country faded from the headlines. This argument is belied, however, by numerous indications that the market for Khmer art has steadily grown over the quarter-century. During this time period, the annual number of foreign tourists to Cambodia has increased from zero to over two million, and counting. Numerous museums across the world have established or expanded significant collections of Khmer art and hosted major temporary exhibitions of it. This increased exposure has likely lead to increased demand. Furthermore, art collectors have begun to turn away from the standards of the Classical world, and to the more exotic reaches of Asia and Latin America. Due to all this, it is more likely that the popularity for Khmer art is at an all time high, rather than an all time low.”

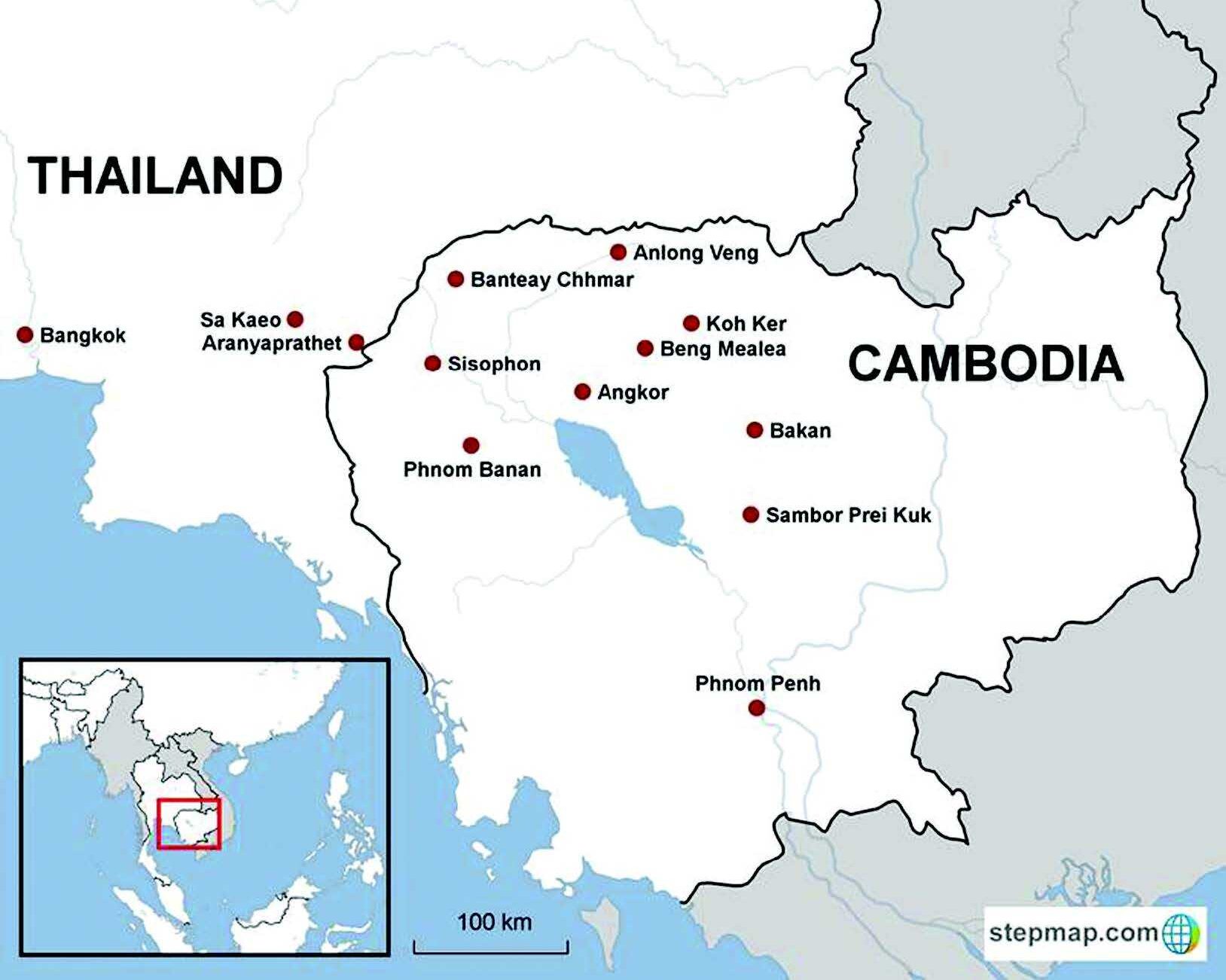

In 2013, Tess Davis and Simon McKenzie visited several archaeological sites around Cambodia in order to assess on the field ‘Temple Looting in Cambodia: Anatomy of a Statue Trafficking Network’ (title of their article in The British Journal of Criminology, vol 54, pp 722 – 740)

Their account, which often reads like a detective story, established Sisophon as a ” trafficking hub” to Thailand, and put a bright light on local brokers. For instance, Thom, based in Sisophon, “ran the temple looting network in a region containing Mount Kulen and Koh Ker, as well as countless other archaeological sites. The territorial limits of his ‘ jurisdiction’ were quite precisely defined; so much so that he was able to identify a street corner in a particular town where ‘his’ territory ended. He controlled the looting in this area in partnership with another man — each region, he said, had two brokers who controlled it together. His relationship with his partner was based on what he described as a very high level of trust. Thom had grown up in this region, but was forced into the military at age 11, during the early years of the Civil War. His ability to ride a horse earned him the coveted post of Khmer Rouge messenger, tasked with delivering missives between their regional camps. In his teenage years, he graduated within the Khmer Rouge from messenger tosoldier. At the height of the purges, Thom defected from the Khmer Rouge, fleeing to the jungles of Kulen. (…) Thom found it difficult to say how many statues he had trafficked in his career, which was active from the 1980s until recently. While leafing through the Khmer antiquities catalogues we had brought to show him, he would occasionally point to modestly sized pieces in bronze and say that he had found ‘thousands’ like them. When pressed to put a number on the volume of his activity, he stressed that like any business, some years were better than others. For example, 1994 – 96 was a bad period, due to heavy fighting in the region. But he remembered mid-1997 to mid-1998 as a ‘good year’ for looters, as the ongoing collapse of the Khmer Rouge opened up the country for the safer internal movement of people and goods. In that 12-month period, he estimated his group had trafficked 92 statues. Some of the objects his network handled were pieces that are now celebrated as among the most important Khmer statues in world collections. For example, he has identified several major statues that he took from the Prasat Krachap temple at Koh Ker.”

One cannot refrain to wonder whether this ‘Thom’, portrayed in 2013, might have been Toek Tik, the repentant looter who helped Cambodian investigators and archaeologists to identify several major Khmer artifacts with illicit origin in 2020 – 2021. While he died of pancreatic cancer on Nov. 29, 2021, his tips have been instrumental in the MET decision to research “proactively” its collection of Khmer art.

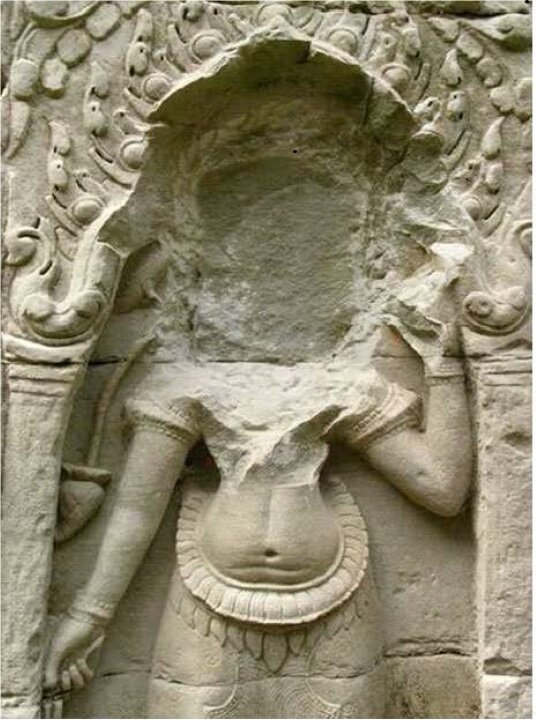

Photo: A sculpture defaced by looters in Preah Vihear temple, 2005 (author’s photo).

Tags: illicit trade, looting, looted art, repatriation, Khmer art, museology, heritage conservation, heritage law, art market

About the Author

Tess Davis

Tess Davis is the Executive Director of the Antiquities Coalition, launched in order to “protect our shared heritage and global security, leading the international campaign against cultural racketeering, the illicit trade in ancient art and artifacts. We champion better law and policy, foster diplomatic cooperation, and advance proven solutions with public and private partners worldwide.”

A lawyer and archaeologist (now affiliated with the University of Glasgow), Tess Davis also teaches cultural heritage law at Johns Hopkins University, and is a Term Member of the American Council on Foreign Relations.

In 2015, the Royal Government of Cambodia knighted Davis for her work to recover the country’s plundered treasures, awarding her the rank of Commander in the Royal Order of the Sahametrei. She co-chaired the International Symposium on looted Khmer art held in Siem Reap, September 2022.