Un voyage a la cour du roi Nom-Rodon (lettre sur le Cambodge, Nocor Khmer)

by L. Charles

A visit to Phnom Penh Royal Palace in 1870, only four years after its construction started.

- Publication

- Bulletin de la Société de géographie commerciale de Bordeaux, Jan 1881, n 2, pp 497-515 (via www.gallica.fr, ed. ADB)

- Published

- 1881

- Author

- L. Charles

- Pages

- 19

- Language

- French

pdf 738.4 KB

Master mariner of the French Merchant Navy, the author came to Phnom Penh as part of a “rescue mission” involving the father a Chinese trader who had some serious issues with King Norodom’s courtiers:

“Je me trouvais à Saigon, en 1870, commandant le François-Félix. Etant venu depuis sept .années consécutives dans les mers de Chine, j’y avais de bonnes et solides amitiés, entre autres MM. Denis frères, les consignataires; M. Blancsubé, l’honorable avocat de Saigon, venait souvent nous voir. Il arrive un jour fort préoccupé: un client chinois, venant du Cambodge, le suppliait de s’y rendre, afin de délivrer son père, mis aux fers, subissant un supplice tous les jours par ordre du roi, qui venait, en outré, de le dépouiller de tous ses biens, lui réclamant 500,000 dollars (environ 2,500,000 fr.). Il expliquait cela ainsi: le grand-père étant mort, le ministre avait déclaré l’héritier cambodgien d’office, ce qui lui permettait d’appliquer la loi du pays, et de s’emparer au nom du roi de la succession. Non seulement on né lui avait rien laissé, mais on lui réclamait 2,500,000 francs. Le roi né voulait le relaxer que sous caution et avait demandé une caution considérable, elle fut trouvée dans la journée et signée par toutes les grandes maisons chinoises de Saigon; il fallait maintenant organiser l’expédition au point de vue pratique; je fus chargé de ce soin.” [“I was in Saigon in 1870, commanding the François-Félix. Having navigated the China seas for seven consecutive years , I had good and solid friendships there, among others Messrs. Denis brothers, the consignees; M Blancsubé, Saigon’s honorable lawyer [and then acting mayor of Saigon, ADB], often came to see us. He arrived one day very concerned: a Chinese client, coming from Cambodia, begged him to go there, in order to free his father, put in irons, undergoing some torture every day by order of the king, who had also just stripped him of all his property, demanding 500,000 dollars. He explained this as follows: the grandfather having died, the minister had declared the heir a Cambodian citizen, which allowed him to apply the law of the country, and to seize the succession in the name of the king. Not only had they left him nothing, but they demanded 2,500,000 francs from him. The king only wanted to release him on bail and had requested a considerable deposit, which was raised that same day among all the great Chinese houses of Saigon; it was now necessary to organize the expedition from a practical point of view, and I was charged with this care.”

French affairists in the early years of the Protectorate

“Nous avions comme personnel, M. Blancsubé et moi, deux domestiques chinois, un cuisinier européen et un pauvre diable de Francais descendant, disait-il, des princes de Chimay-Caraman, mais le tribunal de Salgon lui avait interdit de porter ce titre. Ce brave garçon allait au Cambodge pour y remplir les fonctions d’instituteur des enfants du roi, ce qui me parut étrange, les enfants né parlant pas le francais et leur instituteur né sachant pas un mot de cambodgien.” [“As staff, we had, Mr. Blancsubé and I, two Chinese servants, one European cook and a poor French devil descending, he said, from the princes of Chimay-Caraman, even if the court of Saigon had forbidden him to bear this title. This brave boy was going to Cambodia to fulfill the duties of teacher of the king’s children, which seemed strange to me, the children not speaking French and their teacher not knowing a word of Cambodian.”

ADB Input: French affairist Frédéric Thomas-Caraman had already traveled to Oudong in May 1865, in an attempt to convince the Cambodian king to use his dubious skills. He had succeeded, securing some ‘Traités commerciaux’ with King Norodom, but was driven away by the hostility of the French administrators. After a short stay in France, he was back in the area for King Norodom I’s first visit to Saigon in December 1868.” [See Gregor Miller, Le Cambodge colonial et ses mauvais Francais, trad. Bénédicte du Cheyron Monroe, L’Harmattan, Paris, 2015.]

As for Jules Blancsubé, he acted as mayor of Saigon during several years, and leadered the anti-Napoleonian movement among the French expatriate community in Indochina in 1870, as seen below:

Paul Le Faucheur

“L’interprète du roi, M. Lefaucheur, créole de Bouibou [?], ancien officier du génie, vint nou recevoir; il connmaissalt tout particulierement M. Blancsubé. Aucun de nous n’ayant jamais été au Cambodge, il nous servit d’introducteur aupres de M. Moura, lieutenant de vaisseau détaché au Cambodge comme chargé des affaires de France; nous visitames le télégraphe, et rendez-vous fut pris pour voir le roi le lendemain. M. Lefaucheur nous fit visiter la ville, nous expliqua ses constructions nouvelles, car il joignait à la fonction d’interprete celle d’architecte; plus vraisembablement, il était le factotum du roi. C’est l’homme le plus singulier que j’aie connu: musicien, causeur, buveur, tout allait de pair. Une phrase était entrecoupée ou d’un air de flute, ou d’une gorgée d’absinthe; avec cela né tenant jamais en place, allant, venant, jouant. M. Blancsubé s’informa comment nous serions recus, étant connu le caractere du roi et ses tendances a se considérer comme un demi-dieu.” [“The king’s interpreter, Mr. Lefaucheur, a Creole from Bouibou [?], a former engineering officer, came to receive us; he knew Mr. Blancsubé particularly well. None of us having ever been to Cambodia, he introduced us to Mr. Moura, a lieutnant detached to Cambodia as responsible for French affairs; we visited the telegraph, and an appointment was made to see the king the next day. Mr. Lefaucheur showed us around the city and explained to us its new constructions, since he combined the function of interpreter with that of architect; more likely, he was the king’s factotum. He is the most singular man I have known: musician, conversationalist, drinker, everything went hand in hand. A phrase was interspersed either with a flute tune, or with a sip of absinthe; with this never staying still, coming, coming, playing. Mr. Blancsubé inquired how we would be received, being known the character of the king and his tendencies to consider himself a demigod.”]

Paul Le Faucheur, often described as an adventurer, became father-in-law of Minister of the Palace Thiounn when the daughter he had with Mi Soc, a Cambodian lady of the palace, Malis Le Faucheur, married the famous Cambodian dignitary.

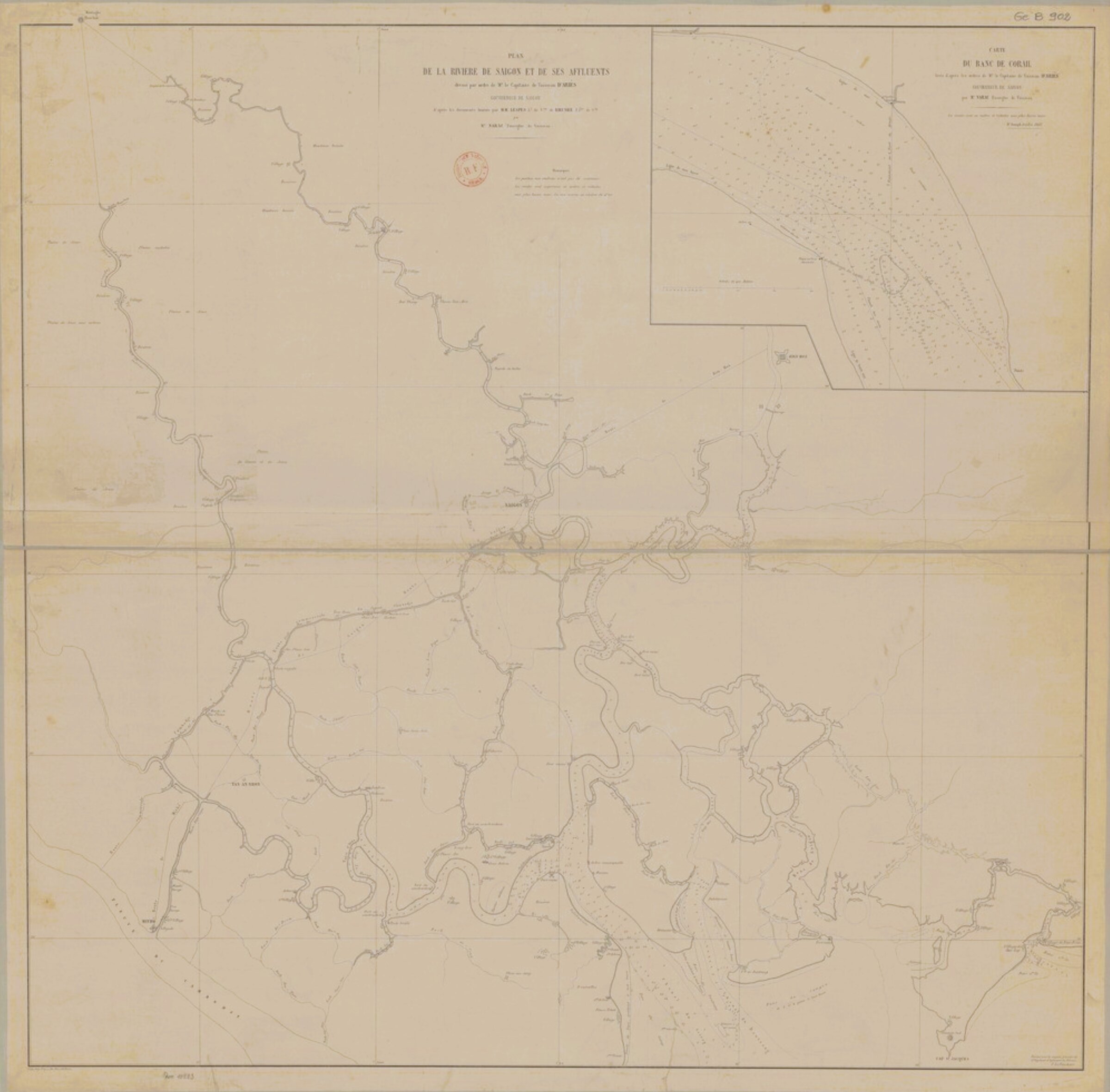

A map of the Saigon River drawn by Paul Le Faucheur as early as 1860 (Plan de la rivière de Saigon et de ses affluents, dressé par ordre de Mr. d’Ariès, gouverneur de Saigon ; d’après les documents fournis par MM. Lepes et Rieunier, par Mr. Narac; dessiné par P. Le Faucheur, 1860 [source: gallica.bnf.fr]

A map of the Saigon River drawn by Paul Le Faucheur as early as 1860 (Plan de la rivière de Saigon et de ses affluents, dressé par ordre de Mr. d’Ariès, gouverneur de Saigon ; d’après les documents fournis par MM. Lepes et Rieunier, par Mr. Narac; dessiné par P. Le Faucheur, 1860 [source: gallica.bnf.fr]

Royal Audience and the Royal Palace in 1870

“Quant à moi, je né voyais qu’une grande maison et y attenant — comme dirait un notaire- un hangar, une halle de petit village; sous la halle, adossés aux piliers de soutènement et assis par térre, six hommes, ayant à leur droite d’énormes coutelas, jouaient ensemble. La façade du palais, assez insignifiante, une grande porte à deux battants; on y montait par une douzaine de degrés environ. Cent mètres avant d’y arriver, nous vimes de chaque coté du chemin une longue flle de Cambodgiens agenouillés, la figure à terre; nous traversâmes cette halle, et au moment où M. Blancsubé mettait le pied sur la première marche du palais, un coup de gong retentit; les deux battants de la porte

s’ouvrirent, et nous montâmes carrément. J’ouvrais des yeux démesurément grands; j’étais curieux, mais nullement ému. M. Blancsubé, tout à fait à la hauteur de la situation, franchit l’enceinte. La pièce où nous fumes introduits était assèz élevée, pas très large, de forme octogonale, un tapis de pied, une petite table sur laquelle étaient disposés des vases en or, à nos pieds des crachoirs en or, pour sièges· de vulgaires chaises rotinées.

“Rien de particulier sur les murailles; tout, à part les vases d’or, était très vulgaire. Au fond et sur le coté, une longue vérandah assez semblable aux portiques de collège. Nous n’attendtmes. pas longtemps; la musique se fit entendre, et, au bruit des gongs, LE ROI PARUT ! Nous nous découvrimes.” [“Myself, I only saw a large house and attached to it — as a notary would say — a shed, like a small village market, and under it, leaning against the supporting pillars and sitting on the ground, six men, having to on their right side huge cutlasses, were playing together. The façade of the palace, quite insignificant, a large double door; we climbed it by about a dozen steps. A hundred meters before arriving there, we saw on each side of the path a long line of kneeling Cambodians kneeling, their faces on the ground; we crossed this hall, and at the moment when Mr. Blancsubé set foot on the first step of the palace, a gong sounded; the two leaves of the door opened, and we went straight up. I opened my eyes disproportionately wide; I was curious, but in no way moved. Mr. Blancsubé, fully up to the task, crossed the enclosure. The room where we were introduced was quite high, not very wide, octagonal in shape, a foot mat, a small table on which were placed gold vases, at our feet gold spittoons, and for seats vulgar rattan chairs. “Nothing special on the walls; everything, apart from the gold vases, was very vulgar. At the back and on the side, a long veranda quite similar to the porticos of a college. We did not wait long; the music started and, at the sound of the gongs, BEHOLD THE KING ! We uncovered ourselves.”]

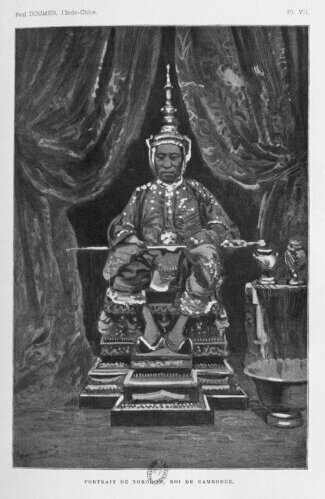

King Norodom I’s portrait from Paul Doumer’s Souvenirs, circa 1890.

“Nom-Rodon est de taille moyenne; il était nu-tête, les cheveux ramenés en forme de pinceau-brosse, le corps

nu jusqu’à la ceinture, les reins ceints d’un pagne, laissant une partie des jambes découvertes, les pieds nus dans des sandales de soie brochée. Les mains et les pieds petits, embonpoint ordinaire; toutes les parties du corps à nu sont couvertes de safran, ainsi que la face; cela lui donnait une couleur jaune d’oeuf pâle. Le safran est la poudre royale, et si par hasard un Cambodgien s’en servait, il pourrait lui en coüter la vie comme· crime capital. La figure est intelligente, les lèvres peu épaisses, le nez peu écrasé, les yeux un peu éteints, ce qui s’explique facilement, vu la vie de mollesse et d’oisiveté qu’il mène. Le roi entra seul; ses femmes agenouillées et échelonnées tout le long de la vérandah, restèrent la tête inclinée, les bras ramenés sur la poitrine. [“Nom-Rodon is of average height; he was bareheaded, his hair pulled back in the shape of a brush, his body naked to the waist, his waist girded by a loincloth, leaving part of his legs uncovered, his feet bare in brocaded silk sandals. Small hands and feet, average stoutness; all parts of the bare body are covered with saffron, as well as the face, giving it a pale egg-yellow color. Saffron is the royal powder, and if by chance a Cambodian used it, it could cost him his life as a capital crime. The face is intelligent, the lips not very thick, the nose not very flat, the eyes a little dull, which is easily explained, given the life of weakness and idleness that he leads. The king entered alone; his women, kneeling and staggered all along the veranda, remained with their heads bowed, their arms drawn to their chests.]

“Le roi se montra aimable, rompit la cérémonie et fit servir l’absinthe du vrai Pernod. Lefaucheur s’y connaissait; deux fort belles filles se détachèrent du groupe et allerent chercher l’abslrtthe et l’eau, mals toujours en se trainant sur les genoux. En revenant elles furent obligées de relever la tête, mais aussitot se voilèrent la face, comme éblouies par l’éclat de Sa Majesté: c’est du reste le cérémonial exigé. Ces pauvrettes, toutes peureuses, étaient charmantes. Il n’y avait pas dé quoi cependant etre ébloui, et pour mon compte le rayonnement prodult par Nom-Rodon me laissait parfaitement froid.” [“Kindly, the king broke the ceremony and had the real Pernod absinthe served. Lefaucheur knew his stuff; two very beautiful girls broke away from the group and went to get the absinthe and the water, but still dragging themselves along on their knees. On returning, they were obliged to raise their heads, but immediately veiled their faces, as if dazzled by the brilliance of His Majesty: this is, after all, the required ceremonial. These poor girls, all timid, were charming. However, there was nothing to be dazzled by, and for my part the radiance produced by Nom-Rodon left me perfectly cold.”

Castles in the air

Like many of his fellow countrymen, the author was convinced the ‘Annam way’, i.e. the forced annexation of vast territories, was the only feasible path to pacification…and appropriation of local natural resources. A strong believer i in military submission of the indigenous people, he was an early proponent of the ‘mission civilisatrice’ [Civilizing Mission], which became the motto of the French Third Republic. And so: “Pour que cette population [cambodgienne] travaille, il né faut qu’une chose: qu’elle soit assurée de pouvolr récolter sans être soumise à des impôts arbitraires, arbltrairement percus et né donnant aux producteurs aucune sécurité. Nous avons une mission civilisatrice envers ces populations si intéressantes, en créant chez elles la plus belle de nos colonies.”[“For this [Cambodian] population to embrace work, only one thing is necessary: that they be assured of being able to harvest without being subjected to arbitrary taxes, arbitrarily collected and giving producers no security. We have a civilizing mission towards these very interesting populations, by creating there the most beautiful of our colonies.”

Tags: Phnom Penh Royal Palace, King Norodom I, French travelers, 1870s

About the Author

L. Charles

L. Charles was a “capitaine au long cours” [master mariner] of the French Merchant Navy and a corresponding member of Société de Géographie commerciale de Bordeaux, created in 1874, who visited Cambodia and the court of King Norodom I as early as 1870.

In addition of his account of Cambodia, we only know that he had navigated “the Chinese seas” since 1863, that he was involved in the first commercial steamer line between Bordeaux and New York, and that he operated in Central America countries.