Claude Farrère

Claude Farrère [penname of Frédéric-Charles Bargone] (27 April 1876, Lyon France — 21 June 1957, Paris) was a French Navy officer and a prolific writer known for his depiction of French colonialism in Saigon with Les civilisés, Prix Goncourt 1905 (he was 29 and was unknown in literary circles), for his exoticism and depictions of faraway places such as Istanbul or Nagasaki.

Admitted to the French Naval Academy in 1894 as wished by his father Pierre Bargone (1826−1892), a Naval infantry colonel, the young “enseigne de vaisseau” [ensign] firstly served in the China seas during three intense formative years, 1897 – 1900. Sending press dispatches to Le Salut public periodical in Lyon from his military assignments [he signed Pierre Toulven], he dreamt of following the path of his hero, the writer-navigator Pierre Loti, with whom he finally met in person in 1903 during a stopover in Istanbul before serving under his command.

Serving in the North and Mediterranean seas, Bargone was also sent to Japan, which he visited from Osaka to Tokyo. Gathering the testimonies of the French sailors aboard the Iéna, he depicted the 1905 naval Battle of Tsushima when the Imperial Japanese Navy defeated the Russian Imperial Navy in La Bataille [The Battle] (1909). The main female character’s name in the novel, Mitsouko, a beautiful and enigmatic Japanese woman inspired perfumer Jacques Guerlain (a friend of the novelists’) in naming his famous perfume.

Fighting in the Navy and the Land Infantry during WWI, he was promoted captain in 1918 but resigned in October 1919 to concentrate on his writing career. With the trust and support of such famed literary mentors as Pierre Benoit, Pierre Loti and Pierre Louÿs (1870−1925), Farrère was elected to a chair at the Académie Française in 1935, winning over Paul Claudel.

The ‘opiomane’ with a nostalgia for empire had then turned into a vocal promoter of French colonialism. In L’Illustration special issue devoted to the 1931 Paris Colonial Exhibition (22 Aug 1931), he signed a piece titled “Angkor et l’Indochine — De l’utilité de la colonisation” in which he claimed that France was the “legitimate heir of the ancient Khmer civilization,” adding

L’Indochine, avant que nous y vinssions, n’était sans doute pas une terre aussi sanglante que le malheureux Maghreb, perdu dans son anarchie féodale. Mais bien des iniquités, bien des violences et bien des misères s’y coudoyaient. Et les temples d’Angkor sont là pour témoigner de toute la beauté pure que l’Indochine avait assassinée, dix ou vingt siècles durant, dans cette anarchie d’un chaos de races ennemies dont les plus fortes cherchaient obstinément l’anéantissement des plus faibles. Quand nos étudiants annamites d’aujourd’hui réclament avec tant d’âpreté leur droit de vivre libres, c’est à dire affranchis de la nation protectrice, ce n’est pas leur indépendance propre qu’ils revendiquent, c’est la restitution de leur droit héréditaire d’opprimer, de molester et de massacrer leurs voisins moins nombreux, moins armés ou moins agressifs. L’Indochine aux Indochinois, cela signifie le massacre ou l’esclavage de tout ce qu’il y a de Cambodgiens, de Laotiens, de Moîs, de Muongs, que sais-je! […] Nous avons interdit, là ou nous sommes, qu’on s’entre-tua et que l’on détruisit le passé, naturel précepteur de l’avenir. L’œuvre est bonne. Continuons ! [Before we went there, Indochina was undoubtedly not as bloody a land as the unfortunate Maghreb lost in its feudal anarchy. Yet many iniquities, much violence, and much misery rubbed shoulders there. And the temples of Angkor are there to bear witness to all the pure beauty that Indochina had murdered, for ten or twenty centuries, in this anarchy of a chaos of enemy races, the strongest of which stubbornly sought the annihilation of the weakest. When our Annamese students of today so fiercely demand their right to live free, that is to say, freed from the protective nation, it is not their own independence that they are demanding, it is the restitution of their hereditary right to oppress, molest, and massacre their less numerous, less armed, or less aggressive neighbors. Indochina to the Indochinese means the massacre or enslavement of all Cambodians, Laotians, Mois, Muongs, and what not! […] We have forbidden, where we are, the killing of one another and the destruction of the past, this natural preceptor of the future. That’s good work. Let’s continue!]

A close friend of Paul Doumer’s, with whom he often lunched, Farrère kept showing his admiration for the latter’s work as former General-Governor of Indochina and President of the French Republic. As the leader of the “Association des ecrivains combattants”, he invited the President at a collective book signing rue Berryer in Paris on 6 May 1932, where Doumer was fatally shot five times by anarchist Paul Gorgulov. The novelist was not seriously wounded in one arm while attempting to protect the politician.

In the 1920s, he ardently supported Kemal Pacha Ataturk’s Young-Turk movement, affecting to date even his sauciest novels with the year of Hejira (Islamic era) until the Turkish leader embraced secularism. As the second world conflict approached, he gave his approval to the French Croix-de-Fer [Iron Cross] fascist movement, authored a favorable biography of collaborationist Admiral Darland and befriend Benito Mussolini in Rome. After WWII, he spoke against the “stupid purge” aimed at collaborationists and at Petain himself, and loved to retire to his villa in Basque country, much as Pierre Loti also used to. In his memoirs (Souvenirs, 1953), he wrote: “J’ai soixante-dix sept ans et je n’ai aucune confiance dans les vieux.” [“I’m 77 and I have no confidence whatsoever in old people.”]

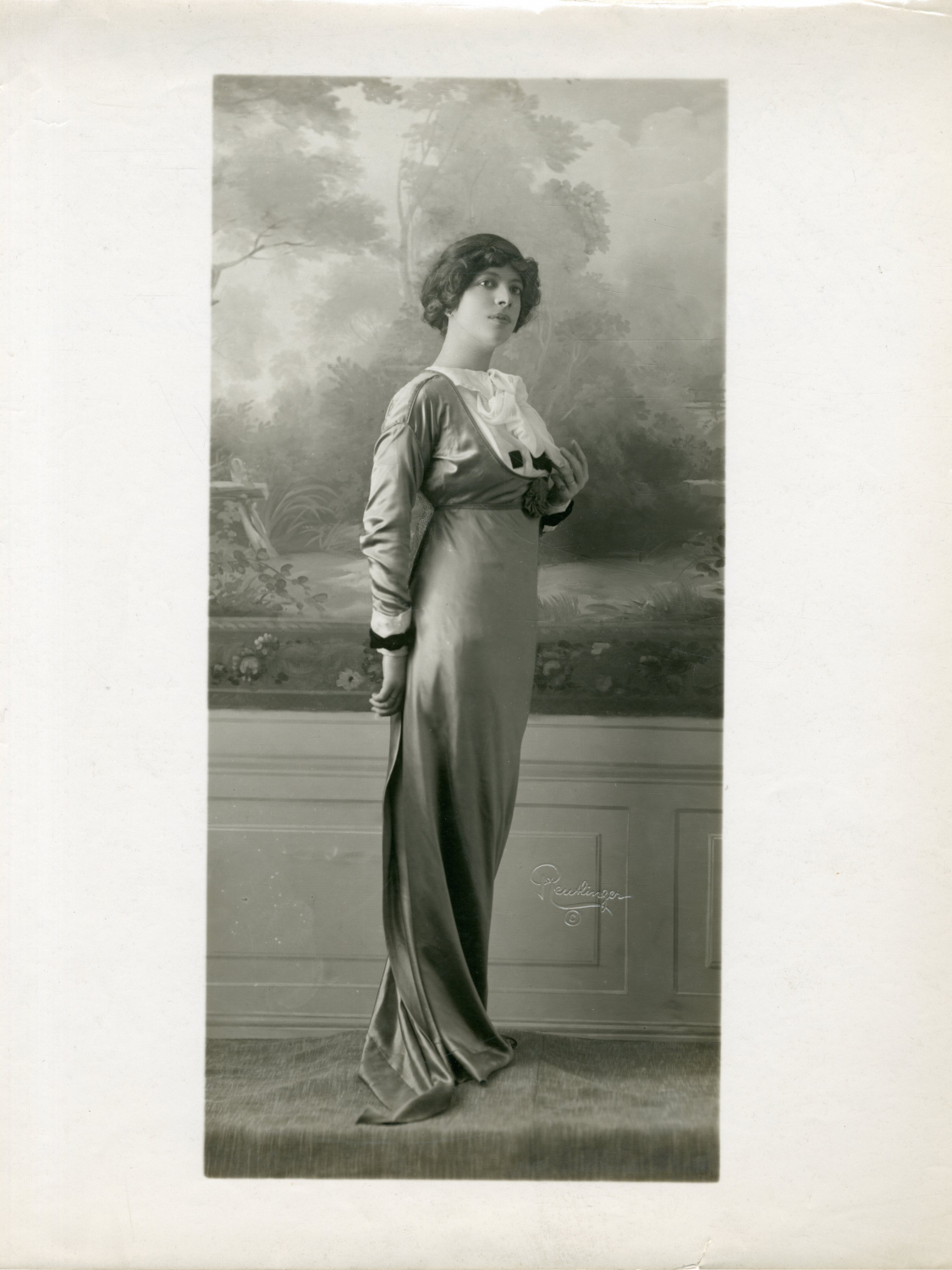

Since 1919, he was married to Joséphine Victorine Roger alias Henriette Roggers (1881−1950), a famed French actress who was to perform in plays by André Gide, Henry Bernstein, Henrik Ibsen, Lucien and Sacha Guitry (even in Rio de Janeiro), and to be a pensionnaire of the Comédie Française from 1923 to 1934. Before their wedding, Henriette had directed the French company at Sankt-Petersbourg “theatre Michel’ [the Mikhailovski Theater], playing for Nicolas I and II’s families, and had befriended the famous tenor Fedor Chaliapine (1873−1938). Rumored to have been the mistress of Nathalie Clifford Barney (1876−1972), a sulfurous American writer based in Paris, and of Russian intellectual Maxime Gorki, Henriette was a successful artist invited into the most exclusive Parisian circles including those of spiritualists and occultists, another fascinating world to both Loti and Farrère who would publish several works of spiritualist fiction along his career — L’autre coté, Les deux masques, la Maison des hommes vivants...

Henriette Roggers portrayed by a) Reutlinger Studio b) Nadar photographer.

Cover of the English versions of The Civilized, April 2025, and The Battle, May 2025, with illustrations by Henri Le Riche (1) and Charles Dominique Fouqueray (2) (courtesy of DatAsia).

Publications

- Le Cyclone [short story published in a 1901 writing challenge organized by Le Salut Public], Lyon, 1902.

- Fumée d’opium, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1904; 6th ed. 1907 [preface by Pierre Louÿs]; repub. 2002, Paris, Mille et Une Nuits; ENG tr. (authorized) by Samuel Putnam as Black Opium, New York, by suscription only, 1929; tr. by Alexander King as Black Opium: Ecstasy of the Forbidden, repub. Ronin Pub., 2015, 200 p.

- Les Civilisés, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1905 [Prix Goncourt], 55 editions, 8 translations; illustr. by Henri Le Mire, Paris, Collection des Dix Veuve Romagnol, 1926; illustr. by Pierre Falké, Paris, Editions Mornay, 1931; ENG tr by Pedro Rodriguez as The Civilized — Decadence and Damnation in French Indochina, Kent Davis and Henri Copin eds, DatAsia, April 2025.

- L’homme qui assassina, Paris, 1906; 1921 (illus. Gérard Cochet, Georges Crès & Cie); 1926 (illus. Henri Farge, Ed. d’art Devambez).

- Pour vaincre la mer, Paris, 1906.

- Mademoiselle Dax, jeune fille, Paris, 1907.

- Trois hommes et deux femmes, Paris, Les Bibliophiles fantaisistes,1909.

- La Bataille, Paris, Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1909; ENG as The Battle — Mitsouko Amidst a Clash of Empires, DatAsia, May 2025.

- Les Petites Alliées, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1910.

- Thomas l’Agnelet, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1911.

- La Maison des hommes vivants, Paris, Librairie des Annales, 1911.

- Dix-sept histoires de marins, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1914.

- Quatorze histoires de soldats, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1916.

- La Veille d’armes, piece en cinq actes representee pour la première fois le 15 janvier 1917, [with Lucien Népoty], Paris, Flammarion, 1917.

- La Dernière Déesse [dedicated to Maréchal Pétain], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1920.

- Les Condamnés à mort, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1920.

- Roxelane [illus. by B. Poggioli], Paris, Edouard-Joseph Editeur, 1920.

- L’Opium ou l’alcool, Paris, Edouard-Joseph, 1920 [by suscription only, preface to Alfred Musset’s L’Anglais mangeur d’opium]

- La Vieille Histoire, comedie en trois actes [illus. by Constant Le Breton, Paris, Edouard-Joseph, 1920.

- Bêtes et gens qui s’aimèrent, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1920.

- Croquis d’Extrême-Orient-1898, [‘Pierre Toulven’s chronicles] Paris, A. Messein, 1921.

- L’Extraordinaire Aventure d’Achmet Pacha Djemaleddine, pirate, amiral, grand d’Espagne et marquis, avec six autres singulières histoires, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1921.

- Contes d’outré- et d’autres mondes, Paris, Les Bibliophiles fantaisistes, 1921.

- Les Hommes nouveaux, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1922.

- Stamboul: drame lyrique en 4 actes et 5 tableaux, d’après le roman de Claude Farrère L’homme qui assassina, et le drame tiré de ce roman par Pierre Frondaie. Poème et musique de Édouard Trémisot, Paris, 1922.

- Lyautey l’Africain, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1922.

- Histoires de très loin ou d’assez près, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1923.

- Ma derniere visite a Loti, Paris, Les amis d’Edouard, 1923.

- Trois histoires d’ailleurs, Paris, Les Bibliophiles fantaisistes, 1923.

- Shahrâ sultane ou Les sanglantes amours authentiques et mirifiques de sultan Shah’Riar, roi de la Perse et de la Chine, et de Shahrâ sultane, héroïne [illustr. by Armand Rassenfosse], Paris, 1923.

- Mes voyages : La promenade d’Extrême-Orient — vol. 1, Paris, 1924.

- Combats et batailles sur mer [with Commandant Paul Chack], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1925.

- Une aventure amoureuse de Monsieur de Tourville, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1925.

- Une jeune fille voyagea, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1925.

- L’Afrique du Nord, Paris, Librairie des arts decoratifs, 1925.

- “Il est mort”, in Le tombeau de Pierre Loüys, Paris, Ed. du monde moderne, 1925, p 47 – 54.

- Mes voyages : En Méditerranée (vol. 2), Paris, E. Flammarion, 1926).

- Le Dernier Dieu, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1926.

- Cent millions d’or, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1927.

- L’École de jazz [theater play, with Dal Médico], Paris, 1927.

- Les Tribulations d’un Chinois en Chine, comedie en trois actes, Paris, Librairie Hachette, 1931.

- La fin de Psyché (fin en prose du Psyché de Pierre Loüys), Paris, Mornay, 1927.

- La Nuit en mer, Paris, libr. Flammarion, coll. “Les Nuits”, 1928.

- Les deux masques de cire, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1928.

- L’Autre Côté, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1928.

- La Porte dérobée [autobiography 1], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1929.

- La Marche funèbre, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1929.

- Loti, Paris, Les amis d’Edouard, 1929.

- Loti et le chef, Paris, Les amis d’Edouard, 1930.

- Turquie ressuscitée, Paris, Editions des cahiers libres, 1930.

Shahrâ sultane et la mer (1931) - “Angkor et l’Indochine,” Exposition coloniale internationale de Paris 1931, L’Illustration special issue 22 Aug. 1931.

- L’Atlantique en rond, Paris, Flammarion, 1932.

- Deux combats navals 1914 [with Cdt Paul Chack], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1932.

- Combats et batailles sur mer 1914 [with Cdt Paul Chack], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1933.

- Les Quatre Dames d’Angora, Paris, Flammarion, 1933.

- Extrême-orient, Paris, Flammarion, 1934 [excerpts from Mes voyages : la promenade d’Extrême-orient].

- Histoire de la Marine française, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1934.

- Le Quadrille des mers de Chine, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1935.

- L’Inde perdue, Paris, Flammarion, 1935; 1992. ed., Paris/Pondicherry, Kailash.

- Sillages: Méditerranée et navires, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1936.

- L’Homme qui était trop grand [with Pierre Benoit], Paris, Editions de France, 1936.

- Visite aux Espagnols (1937)

- Forces spirituelles de l’Orient, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1937.

- Le Grand Drame de l’Asie, Paris, Flammarion, 1938.

- Les Imaginaires, Paris, Flammarion, 1938.

- La Onzième Heure, Paris, Flammarion, 1940.

- François Darlan, Amiral de France et sa Flotte, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1940.

- L’Homme seul, Paris, Flammarion, 1942.

- Fern-Errol, Paris, Flammarion, 1943.

- La Seconde Porte [autobiography 2], Paris, Flammarion, 1945.

- La Gueule du lion, Paris, Flammarion, 1946.

- La Garde aux portes de l’Asie, Journal de Bord, Paris, Gutenberg, 1946.

- La Sonate héroïque [3 short stories], Paris, Flammarion, 1947.

- Escales d’Asie [illus. by Fouqueray] Paris, Laborey, 1947.

- Les Deux Pages du Roy, conte illustré pour enfant, Paris, Iberia, 1947.

- Cent dessins de Pierre Loti commentés par Claude Farrère, Paris, 1948.

- Job, siècle XX, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1949.

- La Sonate tragique, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1950; nd, Kindle ed.

- Le Pavillon sur la dune, Les Œuvres libres, Paris, 1950.

- Je suis marin, Paris, Edition du Conquistador, 1951.

- La Dernière Porte [autobiography 3] Paris, Flammarion,1951.

- L’Île aux images, Les œuvres libres, 1st Aug. 1951.

- Le Traître, Paris, Flammarion, 1952.

- La Sonate à la mer, Paris, Flammarion, 1952.

- L’Élection sentimentale, Paris, Ed. Baudinière, 1952.

- Les Petites Cousines, Paris, Andre Martel, 1952.

- Mon ami Pierre Louÿs, Paris, Domat, 1953.

- Souvenirs, Paris, Librairie A. Fayard, 1953.

- L’amiral Courbet, vainqueur des mers de Chine, Ed. françaises d’Amsterdam, 1953.

- Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1954.

- Le Juge assassin, Paris, André Martin, 1954.

- Lyautey créateur, Paris, Encyclopedie d’outré-mer, 1955.

- Florence de Cao-Bang, [preface by Pierre Chanlaine], Kent-Segep, 1960 [the story of an Eurasian woman clandestinely raised in France, published posthumously at Claude Farrère’s request].

Cover of Fumee d’opium, 1904; cover of the English version, 2015.

- Related Books