Les civilisés [The Civilized]

by Claude Farrère

A gem of French "exotic" literature: Saigon decadence with the 1890s Cambodian uprising in the background.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Paris, Paul Ollendorf

- Edition

- 46th edition digitized by Internet Archive

- Published

- 1905

- Author

- Claude Farrère

- Pages

- 319

- Language

- French

pdf 11.2 MB

As a young Navy officer, the author was commissioned by a provincial newspaper, Le Salut public of Lyon (France), to write “sketches” from the Far East. In Souvenirs [Reminiscing] (Paris, Fayard, 1953), he was to recall:

La Marine, s’étant donc emparée de moi, m’expédia des 1897 en Extreme-Orient. […] Et c’est alors, de 1897 à 1900, qu’ayant vu notre Cochinchine et notre Tonkin, j’écrivis mon premier roman, Les civilisés. Je suis bon critique et je m’en vante. Mon roman terminé, je le relus, le trouvai exécrable, l’enfermai à clé dans un tiroir et me choisis d’autres occupations. [Having taken possession of me, the Navy dispatched me to the Far East as early as 1897. […] It was then, from 1897 to 1900, that I saw our Cochinchina, our Tonkin, and I wrote my first novel, The Civilized. I’m proud to be a trustable critic. As soon as my novel was completed, I read it again, found it appalling, locked it in a drawer and opted for other endeavors. [p 10 – 11]

And yet that same book received the Prix Goncourt five years later, with established French literati such as Pierre Louys, Pierre Benoit, Pierre Loti and the Goddess of French Decadent movement, Rachilde [see below] singing high praise. It was a triumph of colonial literature that irked the real colonials in Indochina — “abject, degrading, pornographic” were some of the adjectives used in the colonial press — and inadvertently cracked open a lingering question in the “Métropole”: were the colonies a mere playground for spoiled experimenters in the dubious art of decadence?

Skirt chaser physician Raymond Mévil, arrogant engineer Georges Torral and “atavistic naval officer” “Jacques-Raoul-Gaston de Civadière, comte de Fierce”, Fierce — “only 25 or 26 years old but seemingly much more poised and bitter than many old men” — dine together in Saigon, the latter just back from eight months spent in a military operation off Nagasaki. Torral has given up to the “vile vice of Saigon”, homosexuality — a word never used throughout the novel -, Fierce is already blasé and on the verge of giving up in the ‘quest for love’, while the good doctor drugs his female patients with cocaine to abuse their bodies.

“Everyone is naked”

These are the “civilized” representatives of the so-called “mission civilisatrice” [“civilizing mission”] France led in “Indochina” until 1953. Or would the term “misfits” be more appropriate? Even if their occupations seem legitimate — curing people, building bridges, defending French interests abroad -, the way they use their privileged status to satisfy selfish needs make them akin to the “adventurers”, the “Bad Frenchmen” colonial powers-that-be instrumented in their enterprise while criticizing them in public. On that level, the tirade of the fictional governor sets the tone:

“Aux yeux unanimes de la nation française, les colonies ont la réputation d’être la dernière ressource et le suprême asile des déclassés de toutes les classes et des repris de justices. En foi de quoi la métropole garde pour elle, soigneusement, toutes les recrues de valeur, et n’exporte jamais que le rébus de son contingent. Nous hébergeons ici les malfaisants et les inutiles, les piqué assiettes et les vide goussets. — Ceux qui défrichent en Indochine n’ont pas su labourer en France ; ceux qui trafiquent ont fait banqueroute ; ceux qui commandent aux mandarins lettrés sont fruits secs de collège ; et ceux qui jugent et qui condamnent ont été quelquefois jugés et condamnés. Après cela, il né faut point s’étonner qu’en ce pays l’Occidental soit moralement inférieur à l’Asiatique, comme il l’est intellectuellement en tous pays…” […] Voilà nos aspirants coloniaux: pourris, et ignares davantage; — prêts d’ailleurs en toutes circonstances à jouer les Napoléon au pied levé. Ils arrivent à Saigon viciés déjà, tarés souvent; et la double influence du milieu anormal et du climat déprimant les complète et les achève. Promptemcnt ils font litière de nos principes, tout en renchérissant sur nos préjugés.” [p 93][ “In the unanimous eyes of the French nation, the colonies have the reputation of being the last resort and the supreme asylum for all classes of downtrodden and repeat offenders. Thus the metropolis would carefully keep for itself all the worthy recruits and never export anything but the rebus of its contingent. We shelter here the evildoers and the useless, the freeloaders and the empty pockets. — Those who clear the land plots in Indochina did not know how to plow in France; those who traffic here have gone bankrupt there; those who command the learned mandarins are dried fruits of college; and those who judge and condemn have sometimes been judged and condemned. Consequently, one should not be surprised that in this country the Westerner is morally inferior to the Asian, as he is intellectually in all countries…” […] Here are our wannabee colonials: rotten, and even more ignorant; — moreover ready in all circumstances to play Napoleon at the drop of a hat. They arrive in Saigon already corrupted, often flawed; and the double influence of the abnormal environment and the depressing climate completes and finishes them off. They promptly make light of our principles, while outbidding our prejudices.”[p 90]

The same writer who some thirty years later would claim that the colonization of Cambodia and Laos was necessary if only to protect these country from the Vietnamese expansionism has been classified as an exponent of French “colonial literature” at its best. Yet there is a dangerously lucid, ferocious undertone in his depiction of Saigon at the turn of the centuy. The “cloaque” [cesspit] which this “Paris of Indochina” is holds at least one advantage — sincerity. As a protaganist remarks,

La vie secrète de Paris ou de Londres est peut-être plus répugnante que la vie de Saigon : mais elle est secrète; c’est une vie à volets clos. Les tares coloniales n’ont pas peur du soleil. Et pourquoi condamner leur franchise? Quand les maisons sont en verre, on fait économie d’illusion et d’hypocrisie. [The secret life of Paris or London is perhaps more repulsive than life in Saigon — but it is secret, a life behind closed shutters. Colonial vices are not afraid of the sun. And why condemn their frankness? When houses are made of glass, one saves on illusion and hypocrisy.] [p. 195]

Before turning into a literary celebrity, when he was only an impulsive and perceptive young man, the author had reflected on the true nature of colonialism in one dispatch to the French liberal gazette Le Salut Public (under the nickname of Pierre Trouvel]:

Il y a un principe colonial qu’on né sait pas en France et qui est pourtant capital. C’est que celui qui retire tout le profit d’une colonie, ce n’est pas le propriétaire, c’est le négociant ; ce n’est pas l’administrateur, le fonctionnaire, c’est celui qui détient les banques, qui accapare les marchés, qui organise les lignes de paquebots, qui importe son industrie à lui et emporte les produits et l’or de la colonie. [There is a colonial principle which is unknown in France and yet crucial — it is that all the profit stemming out of a colony goes not to the owner but to the trader; not the administrator or the civil servant but the ones who own the banks, monopolize the markets, set up the ocean liners, import their own industry and take away the products and the gold of the colony.] (Croquis d’Extreme-Orient — 1898, Paris, Albert Messein, 1921, p 34).

Young officer Fierce instinctively realizes that naked truth of colonial Saigon: the real power here lies in the hands of ‘Cap’taine Malais’, the banker married to the “exquisite, Watteau’s painting-like, blond Marquessa”, the holder of the rice (and other products) revenue farm, the one who had warned him and his comrades in debauchery, one night in a Cholon shady club: “Je né suis pas un civilisé de votre espèce : ma vie plus simple est réglée comme du papier à musique; je gagne de l’argent et je couche avec ma femme.” [“I’m not your kind of civilized person — my simpler life is as ordered as clockwork; I make money and I sleep with my wife.”] [p 119]

In Cochinchina, Malais “the financier” is ready to go as far as the French administrators have dared in Cambodia with the 17 July 1897 “Treaty”: the essence of colonialism requires not only to plunder the resources created by the colonized but also to tax the latter on their mere means of subsistence. Cambodian farmers are up in arms? Their king is protesting the abuse of power from the “protectors”? Never mind!

L’impôt lui [Malais, ADB] a été affermé pour quatre millions seulement, parce que le gouverneur n’osait pas lever cet impôt-là lui-même. Malais ose : il a enrôlé deux mille sacripants armés de Winchesters; et l’impôt donnera huit millions; — mais nous aurons une révolte. [p 145] A propos, quoi y en a nouveau, cap’taine Malais, du côté Grand Lac? — Quoi donc? l’impôt du riz? — Rien, rien.. » Le vieux, prudemment, parlait d’autre chose, détournant ses phrases avec une habileté de diplomate. Les Chinois, silencieux conquérants de l’Indo-Chine, ont tendu sur toutes les villes et tous les villages le réseau de leur négoce; et merveilleusement informés par leur secrète franc-maçonnerie, ils flairent de loin les événements à venir. [p 233] “En ce qui concerne le Grand Lac. Tout le Cambodge est à feu et à sang, et les Siamois s’en melent. Les dépêches sont arrivées cette nuit. Une révolte sérieuse, et trop soudaine : il y a de l’argent anglais là-dessous. Je l’ai prédit, c’est le commencement de la fin… » Il enfourcha son dada favori, et prophétisa des catastrophes. Le fiancé de Sélysette [Fierce, ADB], immobile et silencieux, n’entendait pas. [p 239] A Saigon, l’anxiete première s’était changée en curiosité, puis la curiosité en indifférence. C’était trop long, cette révolte; — et puis trop lointain la guerre s’éternisait au fond du Cambodge, dans ces forêts marécageuses que personne n’avait jamais vues. — Une semaine, on s’était inquiété, troublé même. La vie maintenant recommençait, insouciante et nonchalante. [p250] [The revenue farm has been attributed to him [Malay, ADB] for four million only because the governor did not dare to levy that tax himself. Malay dares: he has enlisted two thousand scoundrels armed with Winchesters; and the tax will yield eight million; — but we will have a revolt. [p 145] By the way, what’s new, Cap’tain Malay, up there near the Great Lake? — What then? The rice tax? — Nothing, nothing…” The old man, prudently, spoke of something else, diverting his words with the skill of a diplomat. The Chinese, silent conquerors of Indo-China, have extended their network of trade over all the towns and villages; and marvelously informed by their secret freemasonry, they can smell from afar the events to come. [p 233] “As for the Great Lake, all of Cambodia is ablaze with blood, and the Siamese are getting involved. The dispatches arrived last night. A serious revolt, and too sudden: there’s English money behind it. I predicted it, it’s the beginning of the end…” He mounted his favorite hobbyhorse and prophesied catastrophes. Sélysette’s fiancé [Fierce, ADB], motionless and silent, wasn’t listening. [p 239] In Saigon, the initial anxiety had turned into curiosity, then curiosity into indifference. This revolt had been going on too long; — and then too far away, the war dragged on in the depths of Cambodia, in those marshy forests that no one had ever seen. — For a week, people had been worried, even troubled. Now life was starting again, carefree and nonchalant. [p250]

Nearly twenty years after Les Civilisés first edition, French writer Francois de Tessan visited Saigon for his book Dans l’Asie qui s’éveille (1923) and still heard the colonists protesting the bad name Farrère had left to them, one of them sighing: “J’entends bien que M. Claude Farrére [sic] n’a voulu se poser ni en moraliste, ni en sociologue. Tout de même, Les Civilisés sont de nature à laisser croire que notre société saigonnaise est presque totalement composée de gens tarés ou qui s’adonnent à des plaisirs pernicieux. Nous n’avons cessé de protester depuis la publication de son livre, et nous réclamons de tous ceux qui viennent ici un jugement impartial, pour que les choses soient remises au point.” [“I understand that Mr. Claude Farrére [sic] did not pretend to pose as a moralist or a sociologist. All the same, The Civilized are of a nature to lead one to believe that our Saigon society is almost entirely composed of people who are deranged or indulge in pernicious pleasures. We have not stopped protesting since the publication of his book, and we demand from all those who come here an impartial judgment, so that things can be put back in order.”

What if this novel were quite simply NOT part of French colonial literature? And what if there never really was a French colonial literature, as another French writer, Pierre Mille, maintained in a noted article (Le Temps, 19 Aug 1909):

“Une œuvre de littérature coloniale, selon moi, serait celle qui eût été produite dans un pays où les Européens sont transplantés depuis un certain temps, par un de ces Européens qui serait né, ou tout au moins y aurait vécu les seules années où l’on possède une sensibilité, où on pénètre dans leur essence la nature et les hommes : je veux dire celles de l’adolescence et de la première jeunesse. Plus tard, on se contente du pittoresque et de l’utilité. Et voilà pourquoi il y a vraiment une littérature [coloniale] anglaise : Kipling était un Anglo-Indien.” “A work of colonial literature, in my opinion, would be one that would have been produced in a country where Europeans have been transplanted for some time, by one of these Europeans who would have been born, or at least would have lived there the only years when one has sensitivity, when one grasps nature and men in their essence, namely those of adolescence and early youth. Later, one is content with the picturesque and the useful. And that is why there is truly an English [colonial] literature: Kipling was an Anglo-Indian.’ [quoted in Saïd Tasra, “Le Roman colonial: Ruptures fondatrices”, Littérature & Sciences Humaines, n 2 – 3, 2019, p 26]

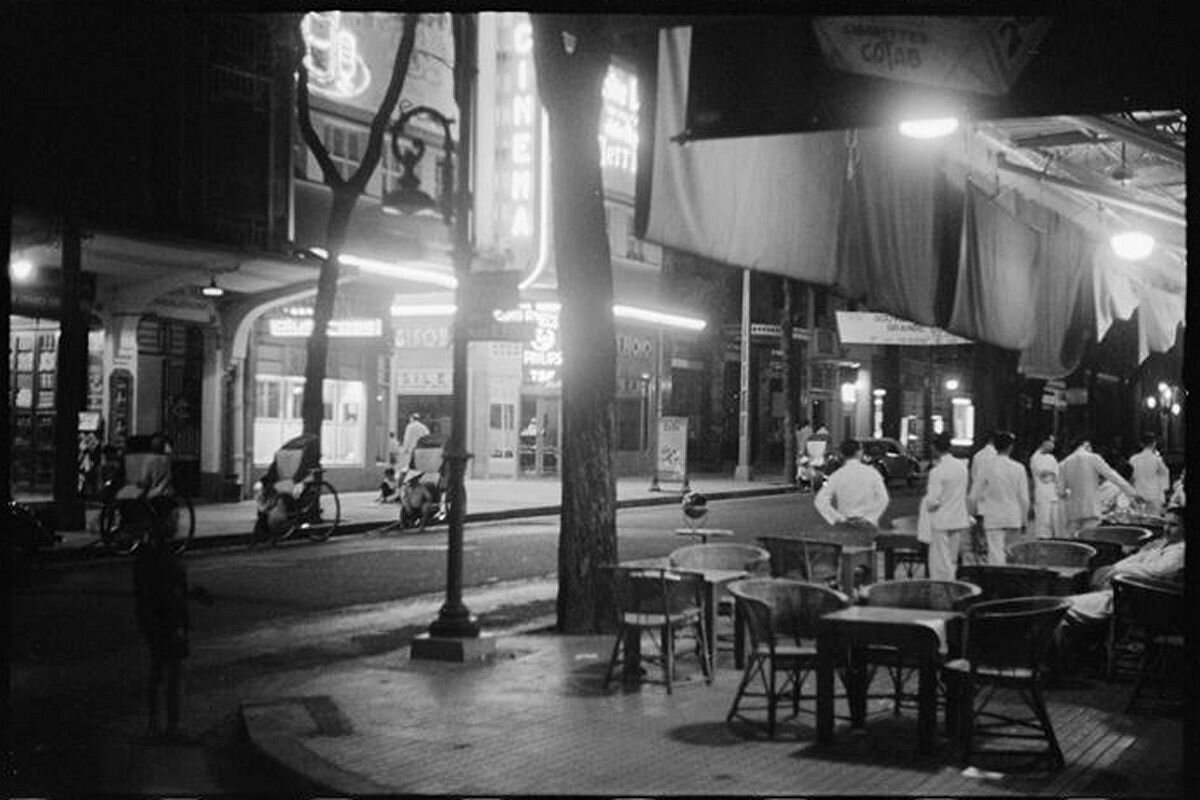

Back to the spectacular opening description of Saigon in Les civilisés, it becomes clear that this world goes round with its own principles and its own magical disorder. It is radically “foreign”, not “in the process of getting civilized:

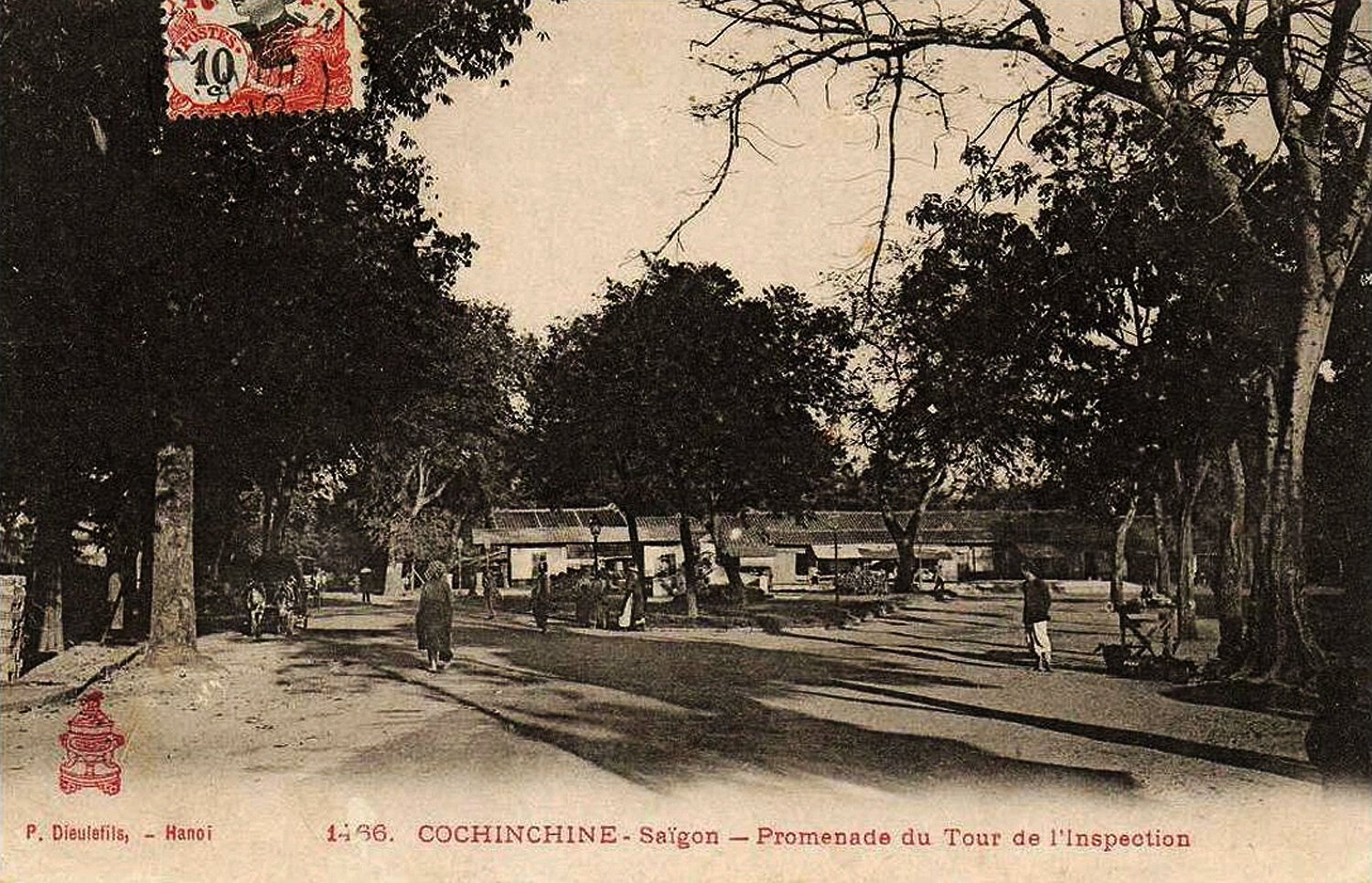

Rue Câtinât, c’est l’agitation mondaine, correcte, — et quand même admirablement libre et impudente parce que la loi souveraine du pays et du climat prime les moeurs importées. Dans le jour cru des réverbères électriques, entre les maisons à vérandas masquées de verdure et de jardins, une cohue bariolée passé et repasse, seulement occupée de son plaisir. Il y a des gens de tous les pays : Européens, Français surtout, coudoyant l’indigène avec une insolence bienveillante de conquérants; et Françaises en robes de soir, promenant lentement leurs épaules sous la convoitise des hommes ; — Asiatiques de toute l’Asie: Chinois du nord, grands, glabres et vêtus de soie bleue ; Chinois du sud, petits, jaunes et vifs; Malabars, rapaces et câlins; Siamois, Cambodgiens, Moïs, Laotiens, Tonkinois; — Annamites, enfin, hommes et femmes tellement pareils qu’on s’y trompe tout d’abord, et que bientôt, on fait semblant de s’y tromper.

On marche à pas désoeuvrés, on cause et on rit, avec des langueurs nées de l’accablante chaleur du jour. On se salue et on se frôle, et les femme vous tendent des mains moites qui brûlent de fièvre. Des parfums forts montent des corsages, et les éventails les mélangent et les jettent au nez de chacun. Une volupté commune agrandit tous les yeux, et la même pensée fait rougir et sourire chaque femme, la pensée que, sous la toile mince des smokings blancs, sous la soie légère des robes pâles, il n’y a rien, ni jupes, ni corsets, ni gilets, ni chemises, — et qu’on est nu, que tout le monde est nu.

[Rue Câtinât is a worldly bustle, decent — and yet admirably free and impudent because the sovereign law of the country and the climate prevails over imported customs. In the harsh light of the electric streetlights, between the houses with verandas hidden by greenery and gardens, a motley crowd goes back and forth, occupied only with its pleasure. There are people from all countries: Europeans, especially French, rubbing elbows with the natives with the benevolent insolence of conquerors; and French women in evening gowns slowly swaying their shoulders under the covetous gaze of men; —Asians from all over Asia: Chinese from the north, tall, hairless, and dressed in blue silk; Chinese from the south, small, yellow, and lively; Malabars, rapacious and cuddly; Siamese, Cambodians, Moi, Laotians, Tonkinese; —Annamites, finally, men and women so alike that we are mistaken at first, and soon we pretend to have been mistaken.

We walk with idle steps, we talk and we laugh, with a languor born of the oppressive heat of the day. We greet each other and brush against each other, and the women extend sweaty hands that burn with fever. Strong perfumes rise from the bodices, and fans mix them and throw them in everyone’s face. A shared voluptuousness widens all eyes, and the same thought makes every woman blush and smile, the thought that, beneath the thin canvas of the white tuxedos, beneath the light silk of the pale dresses, there is nothing, no skirts, no corsets, no vests, no shirts — and that we are naked, that everyone is naked. [p 21 – 2]

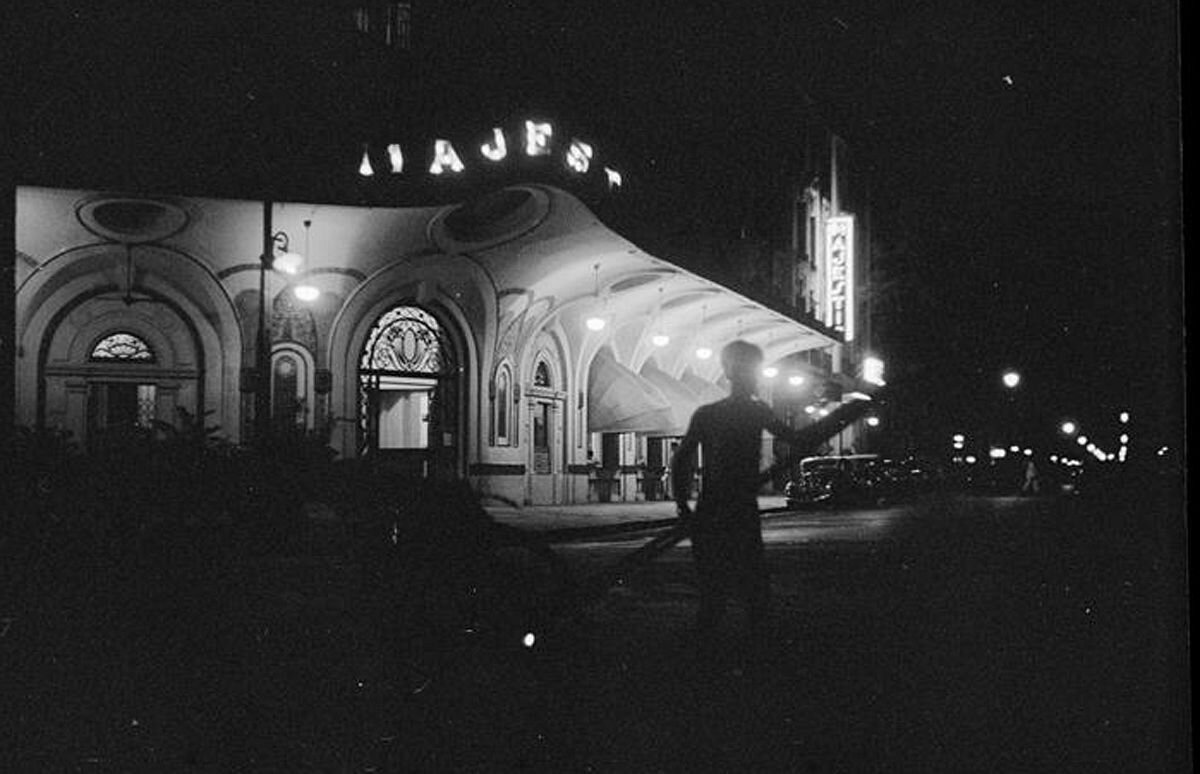

Backseat Tryst on the Promenade

Before reaching the scene that made prudish readers blush and shiver in 1905, let’s share this objective summary of a multi-faceted novel, an abstract penned in the style of literary criticism:

Les Civilisés se déroule en Indochine au début du XXe siècle et présente l’histoire de quelques coloniaux, des militaires, mais aussi des personnages qui vivent dans le sillage de la colonisation et se considèrent comme des exilés ; leur mot d’ordre est le minimum d’efforts pour le maximum de jouissance. Trois figures se détachent d’une société qui vit beaucoup sur elle-même : d’abord un médecin, cocaïnomane décadent qui drogue ses patientes pour obtenir leurs faveurs et qui est décrit comme « un Civilisé, c’est-à-dire une plante de serre, modifiée, déformée, atrophiée par une culture maniaque » ; ensuite un ingénieur opiomane et homosexuel, – il s’adonne au “vice répugnant de Saigon”– ; enfin, un jeune officier de marine dépravé et sceptique, “irrémédiablement pourri par sa vie antérieure », pour qui les trois couleurs du drapeau sont “bleu de choléra, blanc de famine, rouge de sang frais”. Ce marin de la Royale entrevoit une issue quand il rencontre une vraie jeune fille, héritière de valeurs jugées surannées à Saigon. De cette “plèbe coloniale” où s’agitent militaires et fonctionnaires animés d’un même individualisme mesquin émerge un riche banquier à qui sont affermés les impôts de la colonie ; jadis soldat et marin, cet homme énergique mène une vie qu’il dit “réglée comme du papier à musique : je gagne de l’argent et je couche avec ma femme.” [The Civilized takes place in Indochina at the beginning of the 20th century and presents the story of some colonials, soldiers, but also characters who live in the wake of colonization and consider themselves exiles; their motto is the minimum of effort for the maximum of pleasure. Three figures stand out from a society that lives very much in isolation: first a doctor, a decadent cocaine addict who drugs his patients to obtain their favors and who is described as “a Civilized, that is to say a greenhouse plant, modified, deformed, atrophied by a manic culture”; then an opium-addicted and homosexual engineer, – he indulges in the “repugnant vice of Saigon” – ; finally, a young depraved and skeptical naval officer, “irremediably rotten by his previous life”, for whom the three colors of the flag are “cholera blue, famine white, fresh blood red”. This sailor of the “Royale” sees a way out when he meets a real young girl, heiress to valuesconsidered outdated in Saigon. From this “colonial plebs” where soldiers and civil servants fuss around, animated by the same petty individualism, emerges a rich banker to whom the colony’s taxes are leased; once a soldier and sailor, this energetic man leads a life that he says is “regulated like clockwork: I earn money and I sleep with my wife.”[Michel Leymarie, “Au temps de « la plus grande France », le Goncourt aux colonies : Les Civilisés ; Dingley, l’illustre écrivain ; Batouala” in Les Goncourt dans leur siècle: Un siècle de “Goncourt”, Jean-Louis Cabanès, Pierre-Jean Dufief, Robert Kopp and Jean-Yves Mollier eds, Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2005, p 305 – 16. ISBN 978 – 2‑7574 – 2253‑3.]

The turn-of-the-century Promenade is both the Champs Elysees and the Bois de Boulogne of Saigon, a social display of wealth - with the horse carriages called “victorias”, under the wheels of one Dr Mévil will perish without fulfilling his dream to conquer its owner, Madame Malais — and elegance, and also a place to both hide and show off one’s sexual desire, the time-honored combination of voyeurism and exhibitionism like when the male trio takes for a rough ride actress and seductress Hélène Liseron:

Après, ce fut l’arroyo qui borne le Jardin et le pont de briques roses; l’eau coulait si muette et si noire, que l’arche semblait enjamber du néant. La campagne, au delà, commençait, avec des villages de canhas indigènes trop basses pour qu’on les vît dans la nuit.

Hélène écarta sa bouche de Raymond pour balbutier trois mots qu’on né comprit pas. Torral et Fierce, par contenance, regardèrent une minute dehors, puis Fierce se pencha pour prendre du feu à la cigarette de Torral, tous deux indifférents. Hélène, dont on voyait les bras au cou de son amant, s’agitait de mouvements lents et rythmés, et poussait de grands soupirs et des plaintes… Une voiture venant à leur rencontre les croisa dans le temps d’un éclair. D’autres survinrent. La route tournait à gauche, et se prolongeait en allée de parc, joliment encadrée de pelouse et de bosquet. C’était l’Inspection, — les Acacias de Saigon, où la mode est de se promener la nuit comme le jour. — Des lanternes luisaient nombreuses, créant un demi jour équivoque et intermittent. Les Victorias marchaient au pas, sur deux files ; et l’on distinguait les visages des gens ; mais on n’échangeait pas de saluts, par discrétion.

D’une secousse des reins et des poignets, Hélène se redressa. Elle respira fort et s’éventa le visage. Fierce, décemment, étendit sa main et fit retomber les plis delà robe; dans ce geste, il rencontra le poignet de la jeune femme, et elle lui serra les doigts rudement, comme pour détendre ses nerfs encore irrités. Mévil, la tête à la renverse dans- l’angle des coussins, était immobile comme un mort.

[…] Dans chaque voiture, il y avait un homme et une femme, — ou deux femmes — ou parfois un homme et un garçonnet — Et tous les couples, sans exception, se serraient plus étroitement qu’ils n’eussent fait avant le coucher du soleil, et prenaient mille sorte de libertés que la nuit né voilait qu’aux trois quarts.

— Jolie ville, dit Hélène Liseron. C’est révoltant.

— Mais point du tout, dit Fierce avec du mépris et de l’indulgence. C’est tout simplement naturel, et d’un bon exemple pour les hypocrites qui se prétendent pudibonds. D’ailleurs, ma chère, c’est un sot préjugé que celui du mystère en ce qui concerne l’amour et le sexe. Franchement, à vous avoir entrevue tout à l’heure, j’imaginais que vous né le partagiez point. Moi-même et beaucoup de mes amis, sommes sans

délicatesse exagérée là-dessus.[Then came the arroyo that bounded the Garden and the pink brick bridge; the water flowed so silently and so black that the arch seemed to span nothingness. The countryside beyond began, with villages of indigenous canhas too low to be seen in the night.

Helen pulled her mouth away from Raymond to stammer three words that were not understood. Torral and Fierce, out of composure, looked outside for a minute, then Fierce leaned over to light Torral’s cigarette, both indifferent. Helen, whose arms could be seen around her lover’s neck, moved with slow, rhythmic movements, and let out deep sighs and moans… A car coming towards them crossed them in a flash. Others arrived. The road turned left and continued as a park path, prettily framed by lawns and groves. It was the Inspection — the Acacias of Saigon, where the fashion is to stroll night and day. Lanterns shone innumerablely, creating an ambiguous and intermittent half-light. The victorias marched in step, in two files; and people’s faces could be seen; but no greetings were exchanged, out of discretion.

With a jerk of her waist and wrists, Hélène straightened up. She breathed deeply and fanned her face. Fierce, decently, stretched out his hand and smoothed down the folds of the dress; in this gesture, he met the young woman’s wrist, and she squeezed his fingers roughly, as if to relax her still-irritated nerves. Mévil, his head thrown back in the corner of the cushions, was motionless as a corpse.

[…] In each carriage, there was a man and a woman, or two women, or sometimes a man and a little boy. And all the couples, without exception, huddled closer than they would have before sunset, and took a thousand kinds of liberties that were only three-quarters veiled by the night.

“Pretty city,” said Hélène Liseron. “It’s revolting.”

“Not at all,” said Fierce with contempt and indulgence. “It’s quite natural, and a good example for hypocrites who claim to be prudish. Besides, my dear, it’s a foolish prejudice to believe that love and sex are a mystery. Frankly, having seen you just now, I imagined you didn’t share it. I, and many of my friends, are not excessively delicate about it.”[p 33 – 6]

Genderism and the Sailor

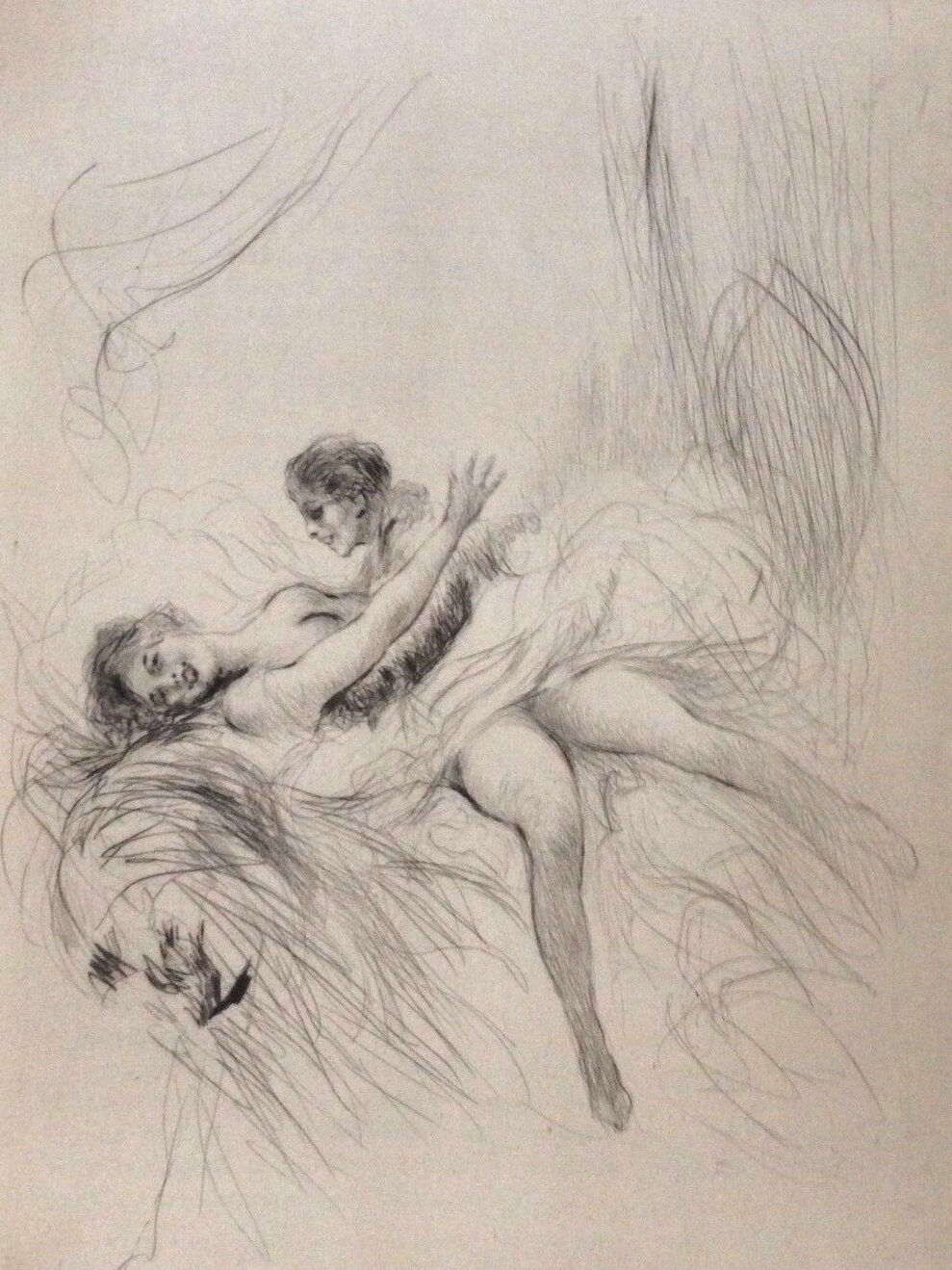

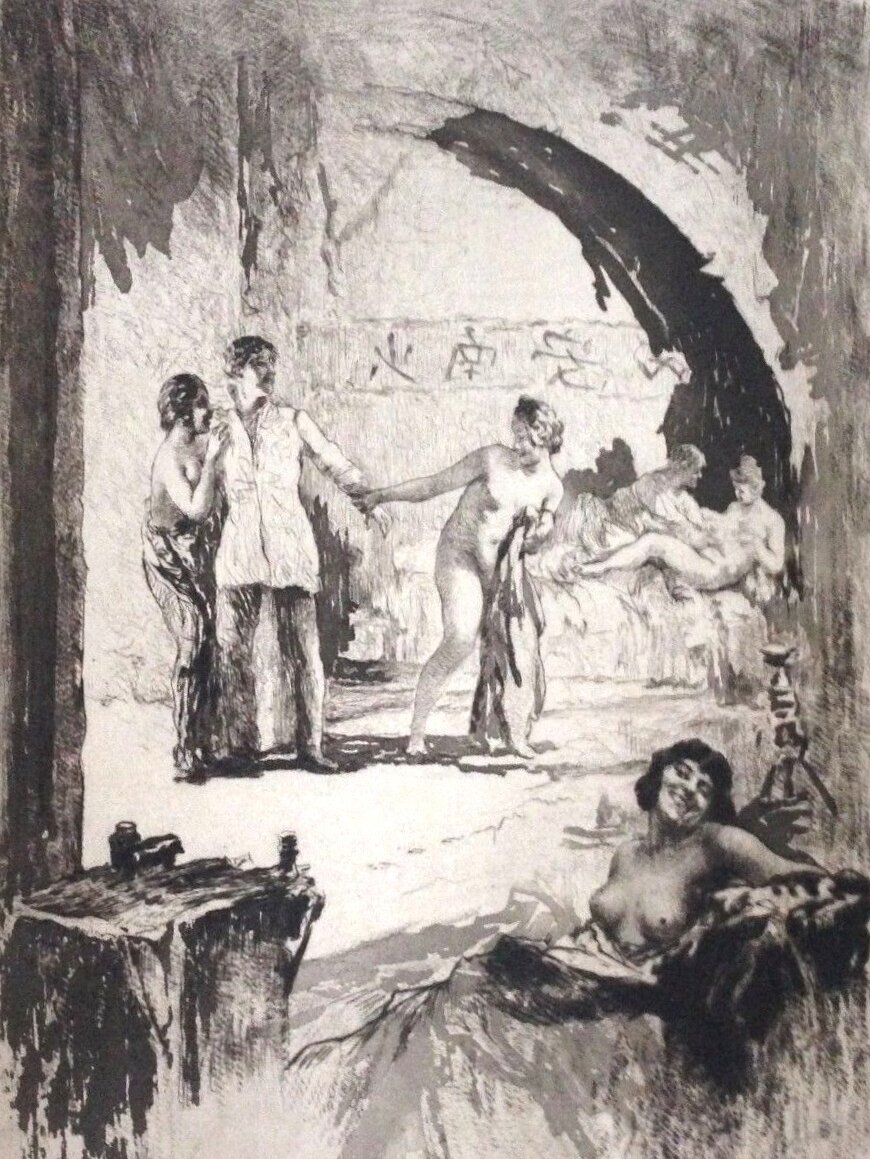

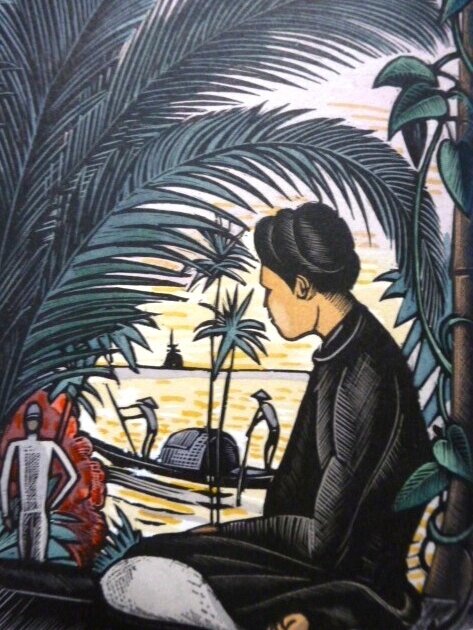

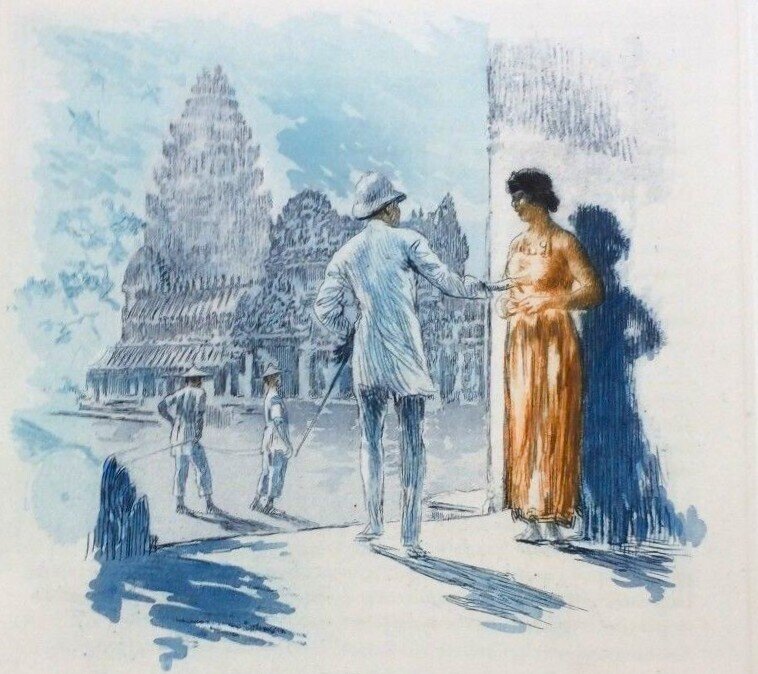

1, 2: edition illustrated by Falké, 1931 ; 3, 4: some illustrations by Henri Le Riche, 1926. Note the accent on colonial realities in the first visual rendition, on conventional erotica in the second one. (photos courtesy of Xavier Dupré)

1, 2: edition illustrated by Falké, 1931 ; 3, 4: some illustrations by Henri Le Riche, 1926. Note the accent on colonial realities in the first visual rendition, on conventional erotica in the second one. (photos courtesy of Xavier Dupré)

1, 2: edition illustrated by Falké, 1931 ; 3, 4: some illustrations by Henri Le Riche, 1926. Note the accent on colonial realities in the first visual rendition, on conventional erotica in the second one. (photos courtesy of Xavier Dupré)

In real life, Claude Farrère wanted nothing more than to emulate his hero, Pierre Loti: always chivalrous with the ladies, refined and decisive in the courtship, never ready to settle down, have dinner twice at the same table, nor even have kids. “Une fois marin, toujours marin”: once a sailor, always a sailor!

A 19th century French naval officer was of course a Janus, with a face of extreme gallantry and one hiding the basest male chauvinism. In Farrère’s case, however, there is a genuine respect when he mentioned women artists in his memoirs, from writers Colette or Margaret Mitchell to his own wife, the actress Henriette Roggers, comparing her talent and professional dedication to the ones of formidable actors such as Charles Boyer or Fedor Chaliapine.

In Les civilisés, men often make appalling remarks about women because that’s what most men did at that time and place. This congai, remarked one of the male characters, “was as pretty as her crossbred race allowed her, with that unfortunate and impossible blend of Hindu bronze and Chinese amber.” [p 94] They did appalling things, too, but even nefarious Mévil is finally brought in front of his failure and vanity by a virgin, the pale Marthe Abel, who let him sniff around her until she rejects in a scene where her words crack like whiplashes on him.

Fierce, the typical macho capable of coldly computing the advantages of Japanese prostitutes over their Annamite fellows, dies under the fire of English vessels while, back in Saigon, his fiancée with an impossible name, the very blond Sélysette Sylva, “répand tout autour d’elle une contagion de chasteté” [“spreads around here a full epidemic of chastity.”] [p 134] The young women not yet corrupted by the male grip are stronger when “they can’t be reached by men’s offensive words.” Like the young Vietnamese official’s daughter, Jeanne Nguyen-Hoc, they show “a smooth forehead and two cold eyes”, or like Anna, the beautiful young Annamite “forgetting her race” to daringly haunt the brothels in search of opium in Farrère’s earlier novel, Fumée d’Opium, they become antique statues, Sphynx statues, not to be reached to or caressed.

A modern, feminist decoding of the novel hears here the anguished battle cry of men endangered by the “Dark Woman”, the “sphynx-like seductress”. This is certainly true for the characters of the novel, but does it apply to the author? In her essay “Colonial Virility and the Femme Fatale: Scenes from the Battle of Sexes in French Indochina” (French Studies, Vol. LIV, No. 4, 2000, p 469 – 478), Jennifer Yee noted that

the besieged state of masculinity is evident, the three protagonists representing as many ways of succumbing to the peril. The engineer Torral indulges in the ‘vices of Saigon’, the new Sodom, with native boys, whereas doctor Mevil, a degenerate womanizer, becomes practically impotent by the age of thirty; his weakness is evident right from the beginning in descriptions which underline his femininity. As for lieutenant de Fierce, he attempts to save himself definitively through his engagement to his own blonde fiancée, but it is too late and he, too, is lost. The doctor’s death itself is highly symbolic: he is crushed beneath the wheels of a victoria, the elegant lady’s carriage whose name is significandy that of a woman and of women’s victory. […] This is the pretext for a reaffirmation of virility made necessary by the disturbance in sexual roles as symbolized by the figure of the femme fatale. The colonial Other is thus effectively reduced to the role of prop in the more abstract colonial backdrop, which provides the terrain for the reconstruction of the heroic individual thanks to its demand for action: bridges must be built, marshes filled in with concrete, natives administered. According to the terms of this Imperialist Exoticism, the successful protagonist should emerge sufficiently cleansed and strengthened from his encounter with the devalorized colonial subject to be able to assert his own status as hero faced with the more pernicious exoticism of the femme fatale.”

Reading again Claude Farrere’s novel, one recalls one remark he made in his memoirs about his selection to the Prix Goncourt 1905: “Rachilde, dupée par ce prénom de Claude, avait fait une vive campagne pour moi, me prenant pour une femme.” [Misled by that first name, Claude, Rachilde had actively agitated on my behalf, believing I was a woman.” This supposed ode to genderism rewarded thanks to a gender confusion? That would be highly ironic, especially as Rachilde, Marguerite Vallette-Eymery (11 February 1860 – 4 April 1953), the egery of the French Decadent literary movement and founder of the periodical Mercure de France, was an expert in gender subversion both in her personal life and in her creative work, what with Monsieur Venus (1884), La Marquise de Sade (1887), La Princesse des ténèbres (1895), L’Heure sexuelle (1898) La Jongleuse (1900), Mon étrange plaisir (1934)?

And let’s note that Annam-based writer Clotilde Chivas Baron dedicated to Claude Farrère her Confidences d’une métisse (Paris, Librairie Charpentier et Fasquelle, 1927), the story of Jeannie, the mixed-race daughter of a French engineer and a Saigon congai who became an “exotic dancer” in Paris to escape the fate of high-class hooker.

In closing, let’s also remark on the alleged “abstract colonial backdrop”. The novel has often been criticized for the superficial notations on indigenous life, the European-centered plot and fantasies. It might be so, but the echoes of the popular rebellion in Cambodia and South Cochinchina are noticeable, as already noted, and the following part reads like a striking premonition of what would happen to French and US regular armies half a century later:

Les canonnières couraient d’arroyo en arroyo ; parfois, — rarement, — elles sondaient les bois de quelques obus. Les insurgés avaient peur d’elles et s’en écartaient; ils dédaignaient les balles et la canonnade, mais leur théologie populaire, — toujours respectée et nourrie par leurs lettrés, — emplissait de démons hostiles ces machines flottantes nuit et jour panachées de fumées et d’étincelles. — Les canonnières allaient et venaient en vain : on fuyait devant elles.

C’étaient alors de longues randonnées inutiles, sur de faux renseignements donnés par de faux espions. — Le village à bombarder demeurait introuvable, à moins qu’il né fût déjà en cendres; les sampans de guerre signalés au fond d’un bras sans issue devenaient magiquement quelques planches pourries. — Les chefs exaspérés tentaient parfois une opération d’envergure : on cernait quinze lieues de pays; on épaississait les lignes, on doublait les grand’gardes; les canonnières barraient chaque arroyo; et l’on n’avançait qu’après mille précautions prises : on marchait en silence à travers les bois vides; le cercle se resserrait : rien. La nuit tombait cependant, et dans les fourrés noirs, une fusillade tardive éclatait; des balles sifflaient jusqu au fleuve, et les tôles des canonnières sonnaient sous les coups; le canon s’en mêlait, c’était enfin une vraie bataille qui durait jusqu’à l’aube. Mais à l’aube, le feu cessait soudain, car on s’était trompé : il n’y avait point d’ennemi. Égaré ou trahi, on s’était fusillé entre soi, on s’était massacré par mégarde. Dix, vingt morts jonchaient le sol. On les enterrait, — et l’on recommençait d’autres erreurs. On tuait et on mourait sans gloire, avec lassitude et ennui.

Les soldats avaient plus de lassitude et les marins plus d’ennui. Les canonnières étaient comme des couvents cloîtrés, d’où l’on né sort pas, et où n’arrivent point les bruits du monde. Chaque soir, ignorantes des événements de la journée, elles mouillaient isolément, en plein milieu de la rivière, loin des rives traîtresses d’où partent les abordages nocturnes, — silencieux et sanglants. Mais si loin que l’on fût, on n’évitait pas la tiédeur humide de la forêt, ni son odeur sensuelle, où vibrent pêle-mêle tous les parfums de fleurs et de feuilles, et l’effluve flévreux de la terre qui fermente. C’étaient des nuits vivantes, pleines de bruissements et de tressaillements. La forêt fourmillait de choses secrètes, qu’on entendait remuer, souffler, haleter. Un murmure formidable montait de cette mer d’arbres; et parfois, des fracas en émergeaient, angoissants à force d’être proches : galopades sur le sol, chutes dans le fleuve, cris de bêtes en chasse ou en amour. Il n’y a rien au monde qui vive plus sensuellement qu’une forêt tropicale.

The gunboats raced from arroyo to arroyo; sometimes — rarely — they probed the woods with a few shells. The insurgents feared them and steered clear of them; they disdained bullets and cannonade, but their popular theology — always respected and nurtured by their scholars — filled these floating machines, night and day, plumed with smoke and sparks, with hostile demons. The gunboats came and went in vain: people fled before them.

These were then long, useless treks, based on false information given by fake spies. The village to be bombarded remained untraceable, unless it was already in ashes; the war sampans reported at the bottom of a dead-end channel magically became a few rotten planks. The exasperated leaders sometimes attempted a large-scale operation: fifteen leagues of country were surrounded; The lines were thickened, the main guards were doubled; the gunboats blocked each arroyo; and they advanced only after taking a thousand precautions: they marched in silence through the empty woods; the circle tightened: nothing. Night fell, however, and in the dark thickets, a late fusillade broke out; bullets whistled as far as the river, and the gunboats’ plates rang under the shots; the cannon joined in, it was finally a real battle that lasted until dawn. But at dawn, the firing suddenly stopped, for they had been mistaken: there was no enemy. Lost or betrayed, they had shot each other, they had massacred each other by mistake. Ten, twenty dead littered the ground. They were buried, — and other errors were made again. They killed and died without glory, with weariness and boredom.

The soldiers were more weary, and the sailors more bored. The gunboats were like cloistered convents, from which one could not leave, and where the sounds of the world could not be heard. Every evening, ignorant of the day’s events, they anchored alone, right in the middle of the river, far from the treacherous banks from which the nocturnal raids — silent and bloody — set out. But no matter how far away one was, one could not avoid the damp warmth of the forest, nor its sensual odor, where all the scents of flowers and leaves vibrate pell-mell, and the stale aroma of the fermenting earth. These were lively nights, full of rustlings and tremblings. The forest teemed with secret things, which one could hear stirring, blowing, panting. A formidable murmur rose from this sea oftrees; and sometimes, crashes emerged from it, distressing because of their proximity: gallops on the ground, falls into the river, cries of animals hunting or in love. There is nothing in the world that lives more sensually than a tropical forest. [p 242 – 3]

Tags: Saigon, gender, sexuality, French Protectorate, French literature, French Navy, tax, 1890s, 1900s, Cambodian uprisings, anticolonialism, colonial literature, dance, women, French novels, Cochinchina, Tonle Sap, Vietnam War

About the Author

Claude Farrère

Claude Farrère [penname of Frédéric-Charles Bargone] (27 April 1876, Lyon France — 21 June 1957, Paris) was a French Navy officer and a prolific writer known for his depiction of French colonialism in Saigon with Les civilisés, Prix Goncourt 1905 (he was 29 and was unknown in literary circles), for his exoticism and depictions of faraway places such as Istanbul or Nagasaki.

Admitted to the French Naval Academy in 1894 as wished by his father Pierre Bargone (1826−1892), a Naval infantry colonel, the young “enseigne de vaisseau” [ensign] firstly served in the China seas during three intense formative years, 1897 – 1900. Sending press dispatches to Le Salut public periodical in Lyon from his military assignments [he signed Pierre Toulven], he dreamt of following the path of his hero, the writer-navigator Pierre Loti, with whom he finally met in person in 1903 during a stopover in Istanbul before serving under his command.

Serving in the North and Mediterranean seas, Bargone was also sent to Japan, which he visited from Osaka to Tokyo. Gathering the testimonies of the French sailors aboard the Iéna, he depicted the 1905 naval Battle of Tsushima when the Imperial Japanese Navy defeated the Russian Imperial Navy in La Bataille [The Battle] (1909). The main female character’s name in the novel, Mitsouko, a beautiful and enigmatic Japanese woman inspired perfumer Jacques Guerlain (a friend of the novelists’) in naming his famous perfume.

Fighting in the Navy and the Land Infantry during WWI, he was promoted captain in 1918 but resigned in October 1919 to concentrate on his writing career. With the trust and support of such famed literary mentors as Pierre Benoit, Pierre Loti and Pierre Louÿs (1870−1925), Farrère was elected to a chair at the Académie Française in 1935, winning over Paul Claudel.

The ‘opiomane’ with a nostalgia for empire had then turned into a vocal promoter of French colonialism. In L’Illustration special issue devoted to the 1931 Paris Colonial Exhibition (22 Aug 1931), he signed a piece titled “Angkor et l’Indochine — De l’utilité de la colonisation” in which he claimed that France was the “legitimate heir of the ancient Khmer civilization,” adding

L’Indochine, avant que nous y vinssions, n’était sans doute pas une terre aussi sanglante que le malheureux Maghreb, perdu dans son anarchie féodale. Mais bien des iniquités, bien des violences et bien des misères s’y coudoyaient. Et les temples d’Angkor sont là pour témoigner de toute la beauté pure que l’Indochine avait assassinée, dix ou vingt siècles durant, dans cette anarchie d’un chaos de races ennemies dont les plus fortes cherchaient obstinément l’anéantissement des plus faibles. Quand nos étudiants annamites d’aujourd’hui réclament avec tant d’âpreté leur droit de vivre libres, c’est à dire affranchis de la nation protectrice, ce n’est pas leur indépendance propre qu’ils revendiquent, c’est la restitution de leur droit héréditaire d’opprimer, de molester et de massacrer leurs voisins moins nombreux, moins armés ou moins agressifs. L’Indochine aux Indochinois, cela signifie le massacre ou l’esclavage de tout ce qu’il y a de Cambodgiens, de Laotiens, de Moîs, de Muongs, que sais-je! […] Nous avons interdit, là ou nous sommes, qu’on s’entre-tua et que l’on détruisit le passé, naturel précepteur de l’avenir. L’œuvre est bonne. Continuons ! [Before we went there, Indochina was undoubtedly not as bloody a land as the unfortunate Maghreb lost in its feudal anarchy. Yet many iniquities, much violence, and much misery rubbed shoulders there. And the temples of Angkor are there to bear witness to all the pure beauty that Indochina had murdered, for ten or twenty centuries, in this anarchy of a chaos of enemy races, the strongest of which stubbornly sought the annihilation of the weakest. When our Annamese students of today so fiercely demand their right to live free, that is to say, freed from the protective nation, it is not their own independence that they are demanding, it is the restitution of their hereditary right to oppress, molest, and massacre their less numerous, less armed, or less aggressive neighbors. Indochina to the Indochinese means the massacre or enslavement of all Cambodians, Laotians, Mois, Muongs, and what not! […] We have forbidden, where we are, the killing of one another and the destruction of the past, this natural preceptor of the future. That’s good work. Let’s continue!]

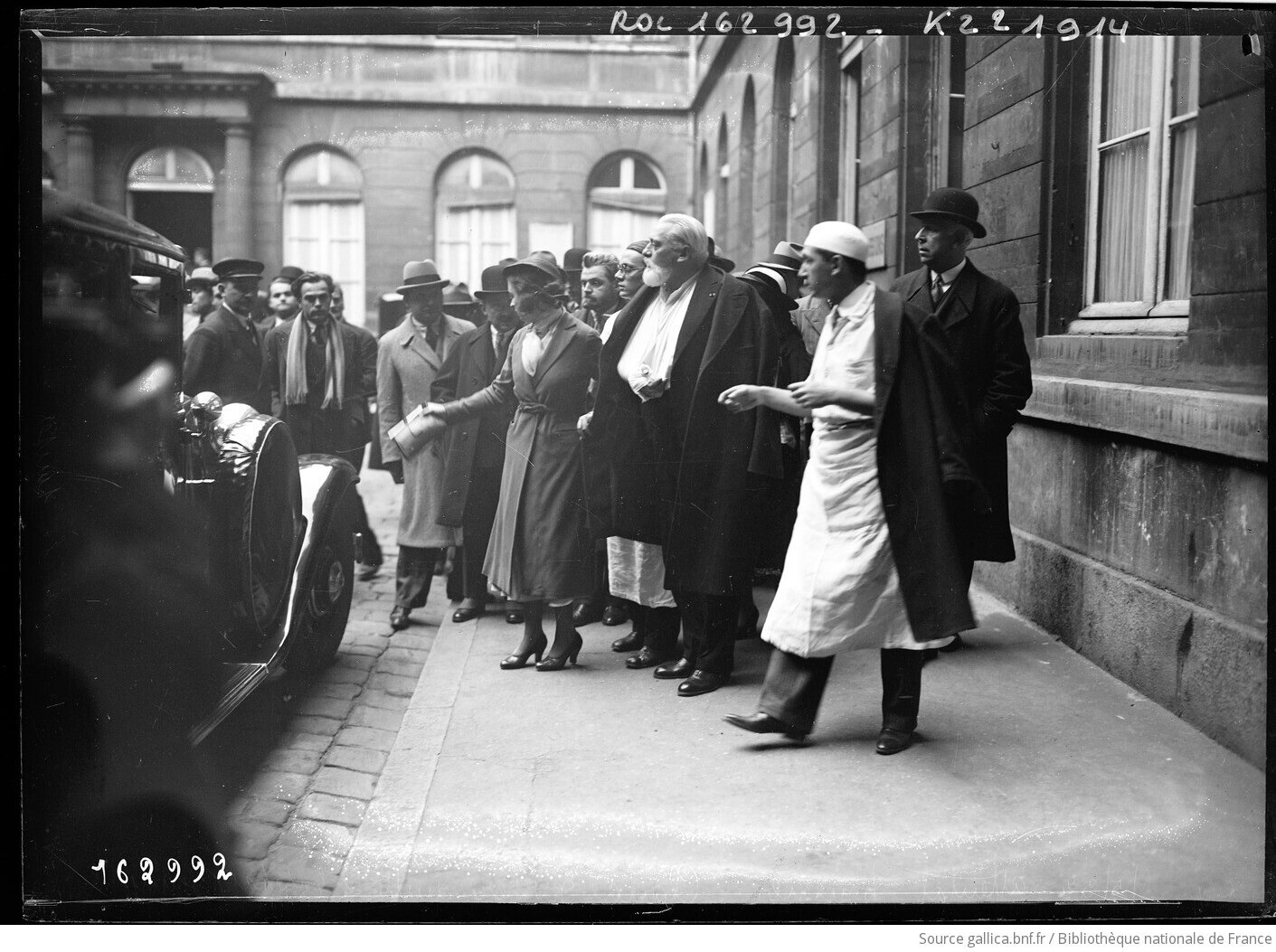

A close friend of Paul Doumer’s, with whom he often lunched, Farrère kept showing his admiration for the latter’s work as former General-Governor of Indochina and President of the French Republic. As the leader of the “Association des ecrivains combattants”, he invited the President at a collective book signing rue Berryer in Paris on 6 May 1932, where Doumer was fatally shot five times by anarchist Paul Gorgulov. The novelist was not seriously wounded in one arm while attempting to protect the politician.

In the 1920s, he ardently supported Kemal Pacha Ataturk’s Young-Turk movement, affecting to date even his sauciest novels with the year of Hejira (Islamic era) until the Turkish leader embraced secularism. As the second world conflict approached, he gave his approval to the French Croix-de-Fer [Iron Cross] fascist movement, authored a favorable biography of collaborationist Admiral Darland and befriend Benito Mussolini in Rome. After WWII, he spoke against the “stupid purge” aimed at collaborationists and at Petain himself, and loved to retire to his villa in Basque country, much as Pierre Loti also used to. In his memoirs (Souvenirs, 1953), he wrote: “J’ai soixante-dix sept ans et je n’ai aucune confiance dans les vieux.” [“I’m 77 and I have no confidence whatsoever in old people.”]

Since 1919, he was married to Joséphine Victorine Roger alias Henriette Roggers (1881−1950), a famed French actress who was to perform in plays by André Gide, Henry Bernstein, Henrik Ibsen, Lucien and Sacha Guitry (even in Rio de Janeiro), and to be a pensionnaire of the Comédie Française from 1923 to 1934. Before their wedding, Henriette had directed the French company at Sankt-Petersbourg “theatre Michel’ [the Mikhailovski Theater], playing for Nicolas I and II’s families, and had befriended the famous tenor Fedor Chaliapine (1873−1938). Rumored to have been the mistress of Nathalie Clifford Barney (1876−1972), a sulfurous American writer based in Paris, and of Russian intellectual Maxime Gorki, Henriette was a successful artist invited into the most exclusive Parisian circles including those of spiritualists and occultists, another fascinating world to both Loti and Farrère who would publish several works of spiritualist fiction along his career — L’autre coté, Les deux masques, la Maison des hommes vivants...

Henriette Roggers portrayed by a) Reutlinger Studio b) Nadar photographer.

Cover of the English versions of The Civilized, April 2025, and The Battle, May 2025, with illustrations by Henri Le Riche (1) and Charles Dominique Fouqueray (2) (courtesy of DatAsia).

Publications

- Le Cyclone [short story published in a 1901 writing challenge organized by Le Salut Public], Lyon, 1902.

- Fumée d’opium, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1904; 6th ed. 1907 [preface by Pierre Louÿs]; repub. 2002, Paris, Mille et Une Nuits; ENG tr. (authorized) by Samuel Putnam as Black Opium, New York, by suscription only, 1929; tr. by Alexander King as Black Opium: Ecstasy of the Forbidden, repub. Ronin Pub., 2015, 200 p.

- Les Civilisés, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1905 [Prix Goncourt], 55 editions, 8 translations; illustr. by Henri Le Mire, Paris, Collection des Dix Veuve Romagnol, 1926; illustr. by Pierre Falké, Paris, Editions Mornay, 1931; ENG tr by Pedro Rodriguez as The Civilized — Decadence and Damnation in French Indochina, Kent Davis and Henri Copin eds, DatAsia, April 2025.

- L’homme qui assassina, Paris, 1906; 1921 (illus. Gérard Cochet, Georges Crès & Cie); 1926 (illus. Henri Farge, Ed. d’art Devambez).

- Pour vaincre la mer, Paris, 1906.

- Mademoiselle Dax, jeune fille, Paris, 1907.

- Trois hommes et deux femmes, Paris, Les Bibliophiles fantaisistes,1909.

- La Bataille, Paris, Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1909; ENG as The Battle — Mitsouko Amidst a Clash of Empires, DatAsia, May 2025.

- Les Petites Alliées, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1910.

- Thomas l’Agnelet, Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1911.

- La Maison des hommes vivants, Paris, Librairie des Annales, 1911.

- Dix-sept histoires de marins, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1914.

- Quatorze histoires de soldats, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1916.

- La Veille d’armes, piece en cinq actes representee pour la première fois le 15 janvier 1917, [with Lucien Népoty], Paris, Flammarion, 1917.

- La Dernière Déesse [dedicated to Maréchal Pétain], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1920.

- Les Condamnés à mort, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1920.

- Roxelane [illus. by B. Poggioli], Paris, Edouard-Joseph Editeur, 1920.

- L’Opium ou l’alcool, Paris, Edouard-Joseph, 1920 [by suscription only, preface to Alfred Musset’s L’Anglais mangeur d’opium]

- La Vieille Histoire, comedie en trois actes [illus. by Constant Le Breton, Paris, Edouard-Joseph, 1920.

- Bêtes et gens qui s’aimèrent, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1920.

- Croquis d’Extrême-Orient-1898, [‘Pierre Toulven’s chronicles] Paris, A. Messein, 1921.

- L’Extraordinaire Aventure d’Achmet Pacha Djemaleddine, pirate, amiral, grand d’Espagne et marquis, avec six autres singulières histoires, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1921.

- Contes d’outré- et d’autres mondes, Paris, Les Bibliophiles fantaisistes, 1921.

- Les Hommes nouveaux, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1922.

- Stamboul: drame lyrique en 4 actes et 5 tableaux, d’après le roman de Claude Farrère L’homme qui assassina, et le drame tiré de ce roman par Pierre Frondaie. Poème et musique de Édouard Trémisot, Paris, 1922.

- Lyautey l’Africain, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1922.

- Histoires de très loin ou d’assez près, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1923.

- Ma derniere visite a Loti, Paris, Les amis d’Edouard, 1923.

- Trois histoires d’ailleurs, Paris, Les Bibliophiles fantaisistes, 1923.

- Shahrâ sultane ou Les sanglantes amours authentiques et mirifiques de sultan Shah’Riar, roi de la Perse et de la Chine, et de Shahrâ sultane, héroïne [illustr. by Armand Rassenfosse], Paris, 1923.

- Mes voyages : La promenade d’Extrême-Orient — vol. 1, Paris, 1924.

- Combats et batailles sur mer [with Commandant Paul Chack], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1925.

- Une aventure amoureuse de Monsieur de Tourville, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1925.

- Une jeune fille voyagea, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1925.

- L’Afrique du Nord, Paris, Librairie des arts decoratifs, 1925.

- “Il est mort”, in Le tombeau de Pierre Loüys, Paris, Ed. du monde moderne, 1925, p 47 – 54.

- Mes voyages : En Méditerranée (vol. 2), Paris, E. Flammarion, 1926).

- Le Dernier Dieu, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1926.

- Cent millions d’or, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1927.

- L’École de jazz [theater play, with Dal Médico], Paris, 1927.

- Les Tribulations d’un Chinois en Chine, comedie en trois actes, Paris, Librairie Hachette, 1931.

- La fin de Psyché (fin en prose du Psyché de Pierre Loüys), Paris, Mornay, 1927.

- La Nuit en mer, Paris, libr. Flammarion, coll. “Les Nuits”, 1928.

- Les deux masques de cire, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1928.

- L’Autre Côté, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1928.

- La Porte dérobée [autobiography 1], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1929.

- La Marche funèbre, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1929.

- Loti, Paris, Les amis d’Edouard, 1929.

- Loti et le chef, Paris, Les amis d’Edouard, 1930.

- Turquie ressuscitée, Paris, Editions des cahiers libres, 1930.

Shahrâ sultane et la mer (1931) - “Angkor et l’Indochine,” Exposition coloniale internationale de Paris 1931, L’Illustration special issue 22 Aug. 1931.

- L’Atlantique en rond, Paris, Flammarion, 1932.

- Deux combats navals 1914 [with Cdt Paul Chack], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1932.

- Combats et batailles sur mer 1914 [with Cdt Paul Chack], Paris, E. Flammarion, 1933.

- Les Quatre Dames d’Angora, Paris, Flammarion, 1933.

- Extrême-orient, Paris, Flammarion, 1934 [excerpts from Mes voyages : la promenade d’Extrême-orient].

- Histoire de la Marine française, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1934.

- Le Quadrille des mers de Chine, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1935.

- L’Inde perdue, Paris, Flammarion, 1935; 1992. ed., Paris/Pondicherry, Kailash.

- Sillages: Méditerranée et navires, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1936.

- L’Homme qui était trop grand [with Pierre Benoit], Paris, Editions de France, 1936.

- Visite aux Espagnols (1937)

- Forces spirituelles de l’Orient, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1937.

- Le Grand Drame de l’Asie, Paris, Flammarion, 1938.

- Les Imaginaires, Paris, Flammarion, 1938.

- La Onzième Heure, Paris, Flammarion, 1940.

- François Darlan, Amiral de France et sa Flotte, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1940.

- L’Homme seul, Paris, Flammarion, 1942.

- Fern-Errol, Paris, Flammarion, 1943.

- La Seconde Porte [autobiography 2], Paris, Flammarion, 1945.

- La Gueule du lion, Paris, Flammarion, 1946.

- La Garde aux portes de l’Asie, Journal de Bord, Paris, Gutenberg, 1946.

- La Sonate héroïque [3 short stories], Paris, Flammarion, 1947.

- Escales d’Asie [illus. by Fouqueray] Paris, Laborey, 1947.

- Les Deux Pages du Roy, conte illustré pour enfant, Paris, Iberia, 1947.

- Cent dessins de Pierre Loti commentés par Claude Farrère, Paris, 1948.

- Job, siècle XX, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1949.

- La Sonate tragique, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1950; nd, Kindle ed.

- Le Pavillon sur la dune, Les Œuvres libres, Paris, 1950.

- Je suis marin, Paris, Edition du Conquistador, 1951.

- La Dernière Porte [autobiography 3] Paris, Flammarion,1951.

- L’Île aux images, Les œuvres libres, 1st Aug. 1951.

- Le Traître, Paris, Flammarion, 1952.

- La Sonate à la mer, Paris, Flammarion, 1952.

- L’Élection sentimentale, Paris, Ed. Baudinière, 1952.

- Les Petites Cousines, Paris, Andre Martel, 1952.

- Mon ami Pierre Louÿs, Paris, Domat, 1953.

- Souvenirs, Paris, Librairie A. Fayard, 1953.

- L’amiral Courbet, vainqueur des mers de Chine, Ed. françaises d’Amsterdam, 1953.

- Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1954.

- Le Juge assassin, Paris, André Martin, 1954.

- Lyautey créateur, Paris, Encyclopedie d’outré-mer, 1955.

- Florence de Cao-Bang, [preface by Pierre Chanlaine], Kent-Segep, 1960 [the story of an Eurasian woman clandestinely raised in France, published posthumously at Claude Farrère’s request].

Cover of Fumee d’opium, 1904; cover of the English version, 2015.