Lucien Fournereau

Michel Louis Lucien Fournereau (15 May 1846, Paris — 19 Dec. 1906, Paris) was a French architect, explorer, archeologist, photographer and illustrator who documented the Khmer temples in the 1880s and 1890s and brought back to France moldings and sculptures exhibited at Paris Musée du Trocadéro, at the 1889 Exposition universelle in Paris and the Exposition internationale et coloniale in Lyon in 1894.

Initially a primary school art teacher in Paris, Fournereau studied architecture and worked ten years (1868−1878) in the reconstruction of Paris buildings damaged in the Prussian invasion before undertaking in 1882 his first mission for the Ministry of the Navy and Colonies, to French Guyana, before the city of Cayenne was devastated by a fire in August 1888. The “ethnographic” aspect of his Guyana posting has yet to be documented: we only found some fine drawings related to urban landscaping and buildings in a Monde illustré (27 Sept. 1888) publication.

Officially assigned to French Cochinchina as an Inspector of Publics Works, Fournerau had joined the first Louis Delaporte Mission to Angkor (1873−1874) as a draughtsman, along with Félix Faraut, Sylvain Raffegeaud, Urbain Basset, Jules Harmand and Étienne Aymonier. Before leaving from Guyana, Fournereau had contacted Delaporte and, expressing his disappointment for not being able to join the second Delaporte Mission in 1881, had requested the French Ministry of Public Education authorization for his own archaeological mission, which he finally obtained in 1886. Arriving in Saigon in December 1887, he joined sculptor Sylvain Raffegeaud, on Delaporte’s recommendation before heading to Angkor [see Julie Philippe, C’est bien comme cela que l’on s’imagine un beau monument de l’Orient”: Louis Delaporte et l’art khmer (1866 – 1924), Ecole nationale des chartes thesis, Paris, 2015, 655 p.]

Trying to find out the guiding principles of the Khmer architectural styles, after exploring Angkor Wat and the main structures close to Angkor Royal Palace (Baphuon, Phimeanakas, Preah Pithu, and also Pre Rup), he left his team at their encampment between the Bayon and Angkor Wat to wander further in the jungle, reaching Preah Khan, Lolei, Prasat Bakong. Delaporte had given him notes and drawings to help him in his prospectios.

Back to Paris on 28 April 1888, Fournereau deposited a part of his finds and plaster caste at Musée des antiquités cambodgiennes du Trocadéro, also called Musée Khmer. His Report to the Ministry mentioned 11 sandstone pieces (balusters, statues and statue heads, stelas, vases and funerary urns), wooden elements, earthenware pieces, and ‘fragments’ or moldings of lintels, columns, frontispieces, a total of 630 pieces. In one draft of said report, he contended that he had to pay ‘hefty sums’ order to pry artworks to the (Siamese?) officer who ‘watched over the ruins like a formidable watchdog.’ He published two large books and several articles on his first mission, much more prolific than Delaporte before him, and omitting to mention the latter’s contribution.

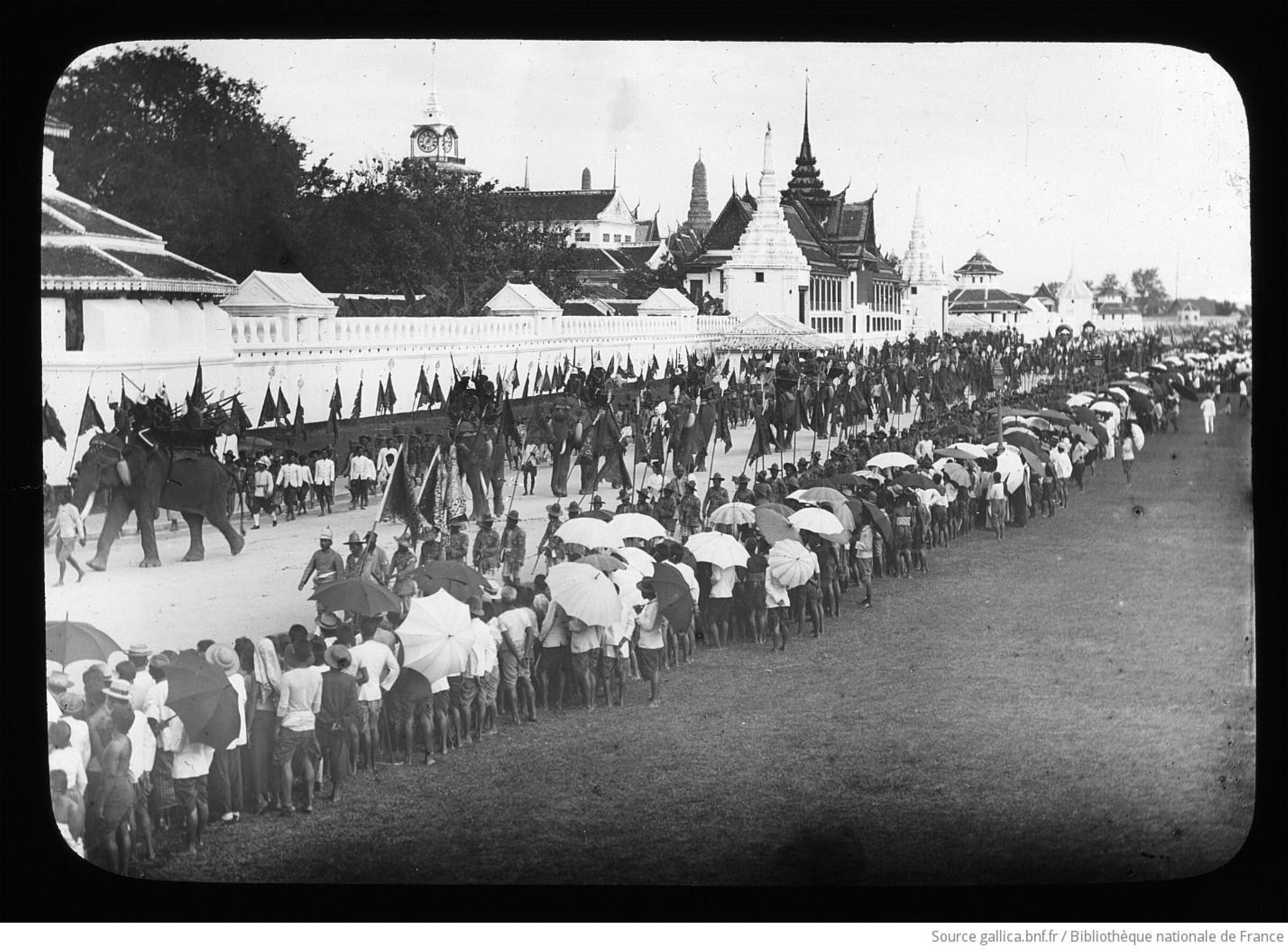

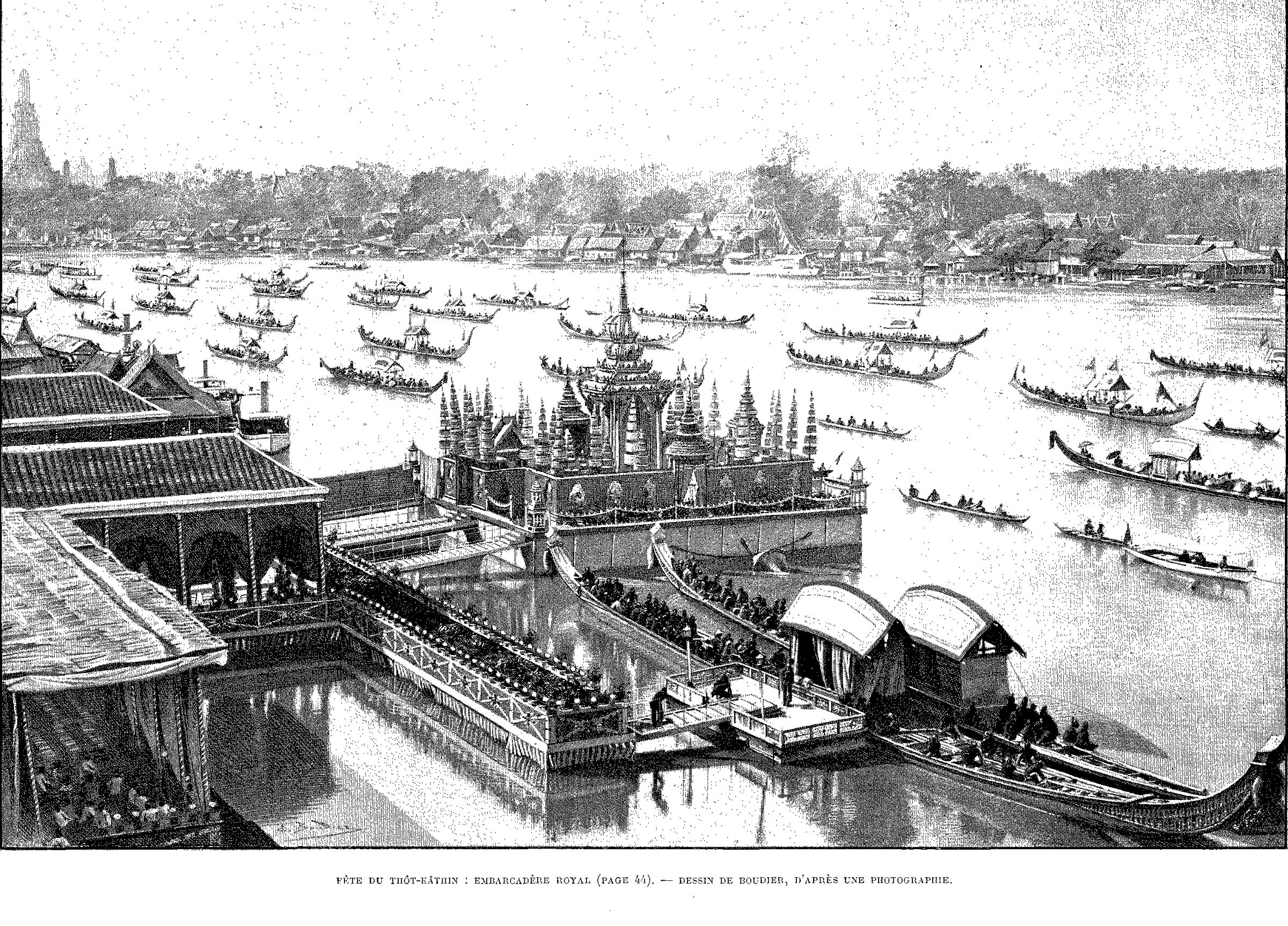

1) This photograph of a procession in front of the Royal Palace of Bangkok was erroneously labelled ‘Phnom Penh’ during one of the numerous screenings of Fournereau’s images by Molteni in Paris [source:gallica.bnf.fr]. 2) The royal barge during Thot Khatin [ทอดกฐิน, offering of the monks’ robes] on Chao Praya River, drawing from Fournereau’s photo [source: L. Fournereau, “Bangkok”, Le Tour du Monde, July 1894.]

1) This photograph of a procession in front of the Royal Palace of Bangkok was erroneously labelled ‘Phnom Penh’ during one of the numerous screenings of Fournereau’s images by Molteni in Paris [source:gallica.bnf.fr]. 2) The royal barge during Thot Khatin [ทอดกฐิน, offering of the monks’ robes] on Chao Praya River, drawing from Fournereau’s photo [source: L. Fournereau, “Bangkok”, Le Tour du Monde, July 1894.]

1) This photograph of a procession in front of the Royal Palace of Bangkok was erroneously labelled ‘Phnom Penh’ during one of the numerous screenings of Fournereau’s images by Molteni in Paris [source:gallica.bnf.fr]. 2) The royal barge during Thot Khatin [ทอดกฐิน, offering of the monks’ robes] on Chao Praya River, drawing from Fournereau’s photo [source: L. Fournereau, “Bangkok”, Le Tour du Monde, July 1894.]

Through his Report (published in the Journal Officiel, 4 October 1888), and moreover in his subsequent books, Fournereau asserted himself as the author of the first comprehensive study on Khmer art, basing his considerations on an important documentation as he took more than 400 photographs and created 89 iconographic works related to the Khmer temples. In the Introduction to Les ruines d’Angkor (1890), he claimed that all the material on Khmer art and architecture published so far “made for an endearing, even amusing read.” A better ‘communicator’ than Delaporte, he seems to have been the first to use the the term “parc” [park] about Angkor, “ce parc immense dont les portes d’entrée sont à elles seules des édifices superbes.” [“this immense park where the entrance gates themselves are splendid stoneworks.”] He also coined the phrase “paysage ruiné” [“landscaped ruins”], an image very much in the ‘Oriental vogue’ of the time and skillfully projected by his pen and watercolor romantic reconstructions of the ancient temples.

From November 1891 to March 1892, he supervised archaeological prospections in the Menam Valley and on the ancient sites of Sukhothai, Lopburi and Ayuthaya, this time officially mandated by the Trocadéro Museum to Siam. In Bangkok, he visited the Royal Palace and, staying at the just opened Oriental Hotel, explored the city, floating markets, pagodas, religious ceremonies and even cremations. His eye for architectural details didn’t catch the lively and colorful charms of Siam’s capital city, which he found ‘uncommonly boring’, especially when compared to Saigon and its Rue Catinat, “si joyeuse et si française” [“so happy, so French”], afflicted by “une insupportable anglomanie” [“insuferable Anglomania”] with nowhere to go at night”: “Chacun vit chez soi : les hommes mariés avec leurs femmes, les célibataires avec leur ennui” [“Everyone stays at home: the married men with their wives, the bachelors with their boredom.”] [‘Bangkok’, Le Tour du Monde, 7 July 1894, p 13].

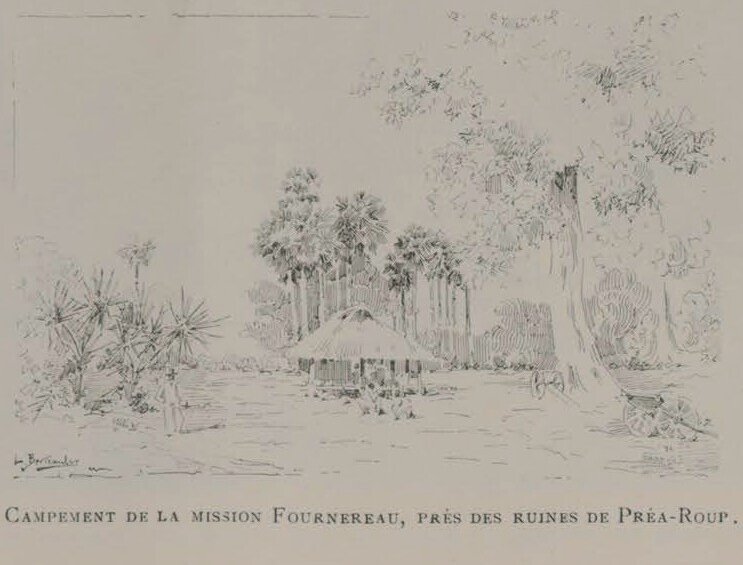

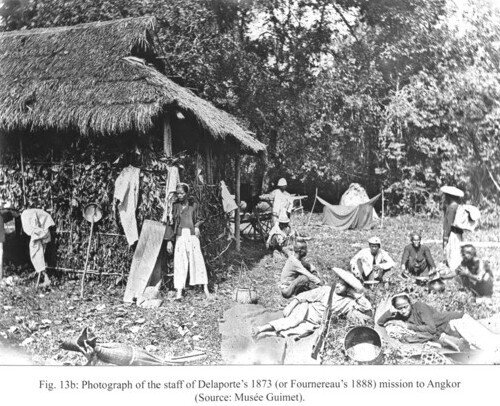

1) Fournereau Mission camp near Pre Rup Temple, drawing by M. Berteaut in Le Monde Illustré, 27 Oct. 1888, p 262. 2) Compare with this photograph of an archaeological encampment at Angkor often attributed to the earlier Delaporte Mission, while researcher Michael Falser supposed it was in fact Fournereau’s. [in “The first plaster casts of Angkor for the French métropole: From the Mekong Mission 1866 – 1868, and the Universal Exhibition of 1867, to the Musée khmer of 1874,” BEFEO 99, 2012, pp. 49 – 92.]

1) Fournereau Mission camp near Pre Rup Temple, drawing by M. Berteaut in Le Monde Illustré, 27 Oct. 1888, p 262. 2) Compare with this photograph of an archaeological encampment at Angkor often attributed to the earlier Delaporte Mission, while researcher Michael Falser supposed it was in fact Fournereau’s. [in “The first plaster casts of Angkor for the French métropole: From the Mekong Mission 1866 – 1868, and the Universal Exhibition of 1867, to the Musée khmer of 1874,” BEFEO 99, 2012, pp. 49 – 92.]

1) Fournereau Mission camp near Pre Rup Temple, drawing by M. Berteaut in Le Monde Illustré, 27 Oct. 1888, p 262. 2) Compare with this photograph of an archaeological encampment at Angkor often attributed to the earlier Delaporte Mission, while researcher Michael Falser supposed it was in fact Fournereau’s. [in “The first plaster casts of Angkor for the French métropole: From the Mekong Mission 1866 – 1868, and the Universal Exhibition of 1867, to the Musée khmer of 1874,” BEFEO 99, 2012, pp. 49 – 92.]

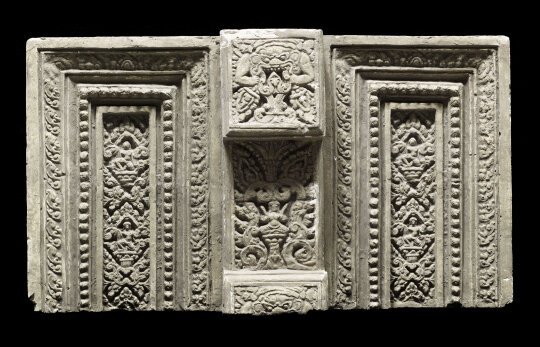

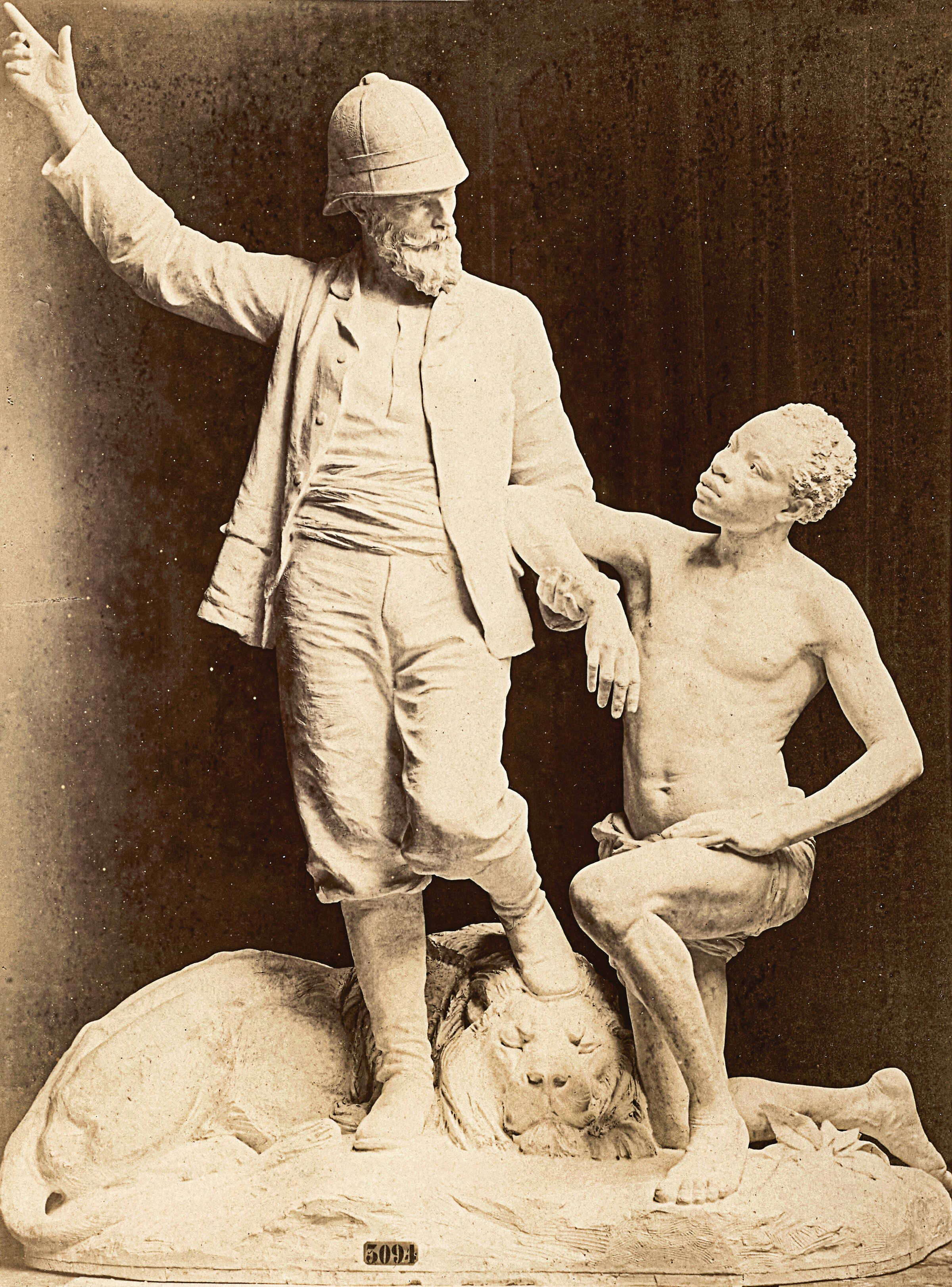

1) One of the 520 casts brought to France by the expedition and credited to Lucien Fournereau and Sylvain Reffageaud: upper part of a Pre Rup temple false door [photo RMN/MuseeGuimet/Thierry Ollivier] 2) As there is no subsisting portrait (photography or painting) of Lucien Fournereau, and we cannot find him in any group photography of the time, and also in line with the quite domineering character depicted by co-worker Raffegeaud, this quite bossy rendition of “L’explorateur” [The Explorer”], seems befitting. Sculpture by Athanase Fossé, 1894 [photo Roland Bonaparte, BNF Les Essentiels].

1) One of the 520 casts brought to France by the expedition and credited to Lucien Fournereau and Sylvain Reffageaud: upper part of a Pre Rup temple false door [photo RMN/MuseeGuimet/Thierry Ollivier] 2) As there is no subsisting portrait (photography or painting) of Lucien Fournereau, and we cannot find him in any group photography of the time, and also in line with the quite domineering character depicted by co-worker Raffegeaud, this quite bossy rendition of “L’explorateur” [The Explorer”], seems befitting. Sculpture by Athanase Fossé, 1894 [photo Roland Bonaparte, BNF Les Essentiels].

1) One of the 520 casts brought to France by the expedition and credited to Lucien Fournereau and Sylvain Reffageaud: upper part of a Pre Rup temple false door [photo RMN/MuseeGuimet/Thierry Ollivier] 2) As there is no subsisting portrait (photography or painting) of Lucien Fournereau, and we cannot find him in any group photography of the time, and also in line with the quite domineering character depicted by co-worker Raffegeaud, this quite bossy rendition of “L’explorateur” [The Explorer”], seems befitting. Sculpture by Athanase Fossé, 1894 [photo Roland Bonaparte, BNF Les Essentiels].

“A Grand monsieur”: Sculptor Raffegeaud about Lucien Fournereau

“Grand Monsieur toujours colère, nous tous ça Chinois vouloir partir; ici même chose prison” [“The Big Monsieur alwas angry, we all Chinese we want go away; here same same jail”]: in a text dated Saigon, 25 Nov. 1888, French sculptor and molder Sylvain Raffegeaud, a major contributor to the Fournereau Mission, reported the baffled reaction of the “Chinese” (most probably Vietnamese or Sino-Vietnamese, as they were brought to Angkor from Saigon) workers to Lucien Fournereau’s ill-tempered and bossy methods. In a few words, Raffegeaud gave a vivid description of one of the first French encampments in Angkor [“Souvenirs de la mission Fournereau aux ruines d’Angkor: Histoire de moulages”, Bulletin de la Societe d’Etudes Indochinoises (BSEI), 2nd sem. 1888, p 139 – 47]:

Il prit tout à coup un ton d’arrogance et de quelqu’un qui né connaît aucune convenance. J’étais tout à fait révolté. Je me disais : comment, entre trois Français, amis et collègues isolés dans le désert, quand aucun de nous né songe à lui porter ombrage, il faut tant d’autorité, ce ton rogue et insolent, une allure plus que militaire et la cordialit bannie? C’était exorbitant. Je vis que son titre de chef de mission le grisait quelque peut et que, sans plus de ménagement, il en prenait possession, d’autant plus fiévrieusement que dans ces solitudes il n’y avait pas de galerie pour rire et qu’il n’aurait aucune retenue. Tout ce pauvre personnel n’a jamais connu que sa voix étranglant de colère pour n’importe quel ordre.

J’ai pensé, depuis, que notre chef de mission avait été chef de service à Cayenne, et qu’il avait dû prendre là le pli à commander des forçats qui convient si peu aux Chinois, travailleurs et dociles. Quand ces gens avaient besoin de quelques piastres pour leur nourriture et que je les lui demandais pour eux, la seule chose qui le touchait, c’était la préséance du chef de mission : « Je suis le chef de la mission, c’est à moi qu’ils doivent demander. » Si je lui faisais part de quelque plainte, le prenant toujours de très haut : “C’est moi le chef de la mission, comment se fait-il qu’on né « vienne pas à moi seul ? ils né connaissent que vous.” L’explication était facile : je les avais choisis et je les dirigeais ; il était tout simple que je leur servisse d’intermédiaire.

Je né me prévaudrai pas de mon métier de mouleur, qui est un accessoire de ma profession ordinaire, mais j’ai été mêlé toute ma vie aux plus grands travaux de Paris ; j’ai pratiqué et j’ai vu a l’oeuvre, et appris ‚les premiers ouvriers tous les secrets des moulages divers-. J’ai, je l’avoue, quelque vanité d’avoir dressé et rendus habiles nos ouvriers chinois, qui ont pu exécuter dans un temps relativement court (2 mois 4 jours) le travail assez considérable de cette mission, 520 pièces.

[…] La photographie m’a rappelé les soirées monotones où M. Fournereau développait [ADB note: the chemical baths weren’t cold enough during the hot days]; pour le besoin du travail, on éteignait les lumières; Kérautret el moi allongions par fois la conversation dans l’obscurité, ou, s’il reposait, je faisais les cent pas dans la clairière, cherchant dans le ciel la Croix du Sud. Les boys et coolies, invisibles dans leur campement à une faible distance, se livraient à des rires, à des chuchotements et bavardages animés ; si les voix s’élevaient trop, celle du maître étouffait par une apostrophe cette vie forcée de sommeiller. Je n’aime pas la solitude silencieuse ; nous étions, à notre passage, chargés d’animer ces paysages; le tempérament d’un seul les rendit mornes et pleins d’ennui; aussi la gaîté de tout ce personnel d’Annamites disparaissait et la fatigue dominait.

Mon regret, dans cette mission, c’est de n’avoir pu faire quelques types, quelques études ethnographiques. J’ai rarement vu, même dans des campagnes retirées de France, des populations aussi douces, aussi inoffensives ; à plusieurs fois j’avais fait part de mon désir à M. Fournereau, et c’eût été facile, soit avec ces Cambodgiens ou Siamois, et surtout avec les bonzes, au caractère de grands enfants. Je né veux pas charger notre chef de mission, qui avait bientôt fait le vide parmi ces indigènes.

[“He suddenly struck the arrogant tone of someone who knows no propriety. I was utterly revolted. I asked myself: how come that, among three Frenchmen, friends and colleagues isolated in the desert, when none of us thinks of offending anyone, so much authority would be required, a harsh and insolent tone, a bearing that is more than military, and cordiality banished? It was exorbitant. I saw that his title of head of mission was intoxicating him somewhat and that, without further consideration, he was taking possession of it, all the more feverishly since in these solitudes there was no gallery to laugh at it and he would have no restraint. All these poor personnel have never known anything but his voice choking with anger at any command.

I’ve since thought that as our head of mission had been head of department in Cayenne, he must have acquired there the habit of commanding convicts, which is so unsuitable for the hardworking and docile Chinese. When these people needed a few piastres for food and I asked him for them, the only thing that affected him was the precedence of the head of mission: “I am the head of the mission, it’s to me that they should ask.” If I voiced any complaint, he always spoke very highly of him: “I’m the head of the mission, how come people don’t come to me alone? They only know you.” The explanation was easy: I had chosen them and trained them; it was quite simple for me to serve as their intermediary.

I won’t boast about my profession as a molder, which is an accessory to my ordinary occupation, but I have been involved all my life in the greatest projects in Paris; I practiced and saw the first workers at work, and learned all the secrets of the various castings. I admit that I am somewhat proud of having successfully trained our Chinese workers, who were able to complete in a relatively short time (2 months 4 days) the considerable work of this mission, 520 pieces.

[…] The photograph reminded me of the monotonous evenings when Mr. Fournereau was developing [ADB note: the chemical baths weren’t cold enough during the hot days]; for the sake of the work, the lights were turned off; Kérautret and I would sometimes continue our conversation in the darkness, or, if he was resting, I would pace up and down in the clearing, searching the sky for the Southern Cross. The boys and coolies, invisible in their camp a short distance away, would engage in laughter, whispers, and animated chatter; If the voices rose too high, the master’s would drown out this life forced to slumber with a scold. I don’t like silent solitude; we were, as we passed by, in charge of bringing these landscapes to life; the temperament of one person made them dull and full of boredom; thus, the gaiety of all these Annamite personnel disappeared and fatigue dominated.

My regret, in this mission, is not having been able to make some models, some ethnographic studies. I have rarely seen, even in remote places of the French countryside, such gentle, inoffensive populations; I had expressed my wish to Mr. Fournereau several times, and it would have been easy, whether with these Cambodians or Siamese, and especially with the monks, who had the disposition of grown children. I do not want to caricature our mission leader but he was soon cut off from these natives.”]

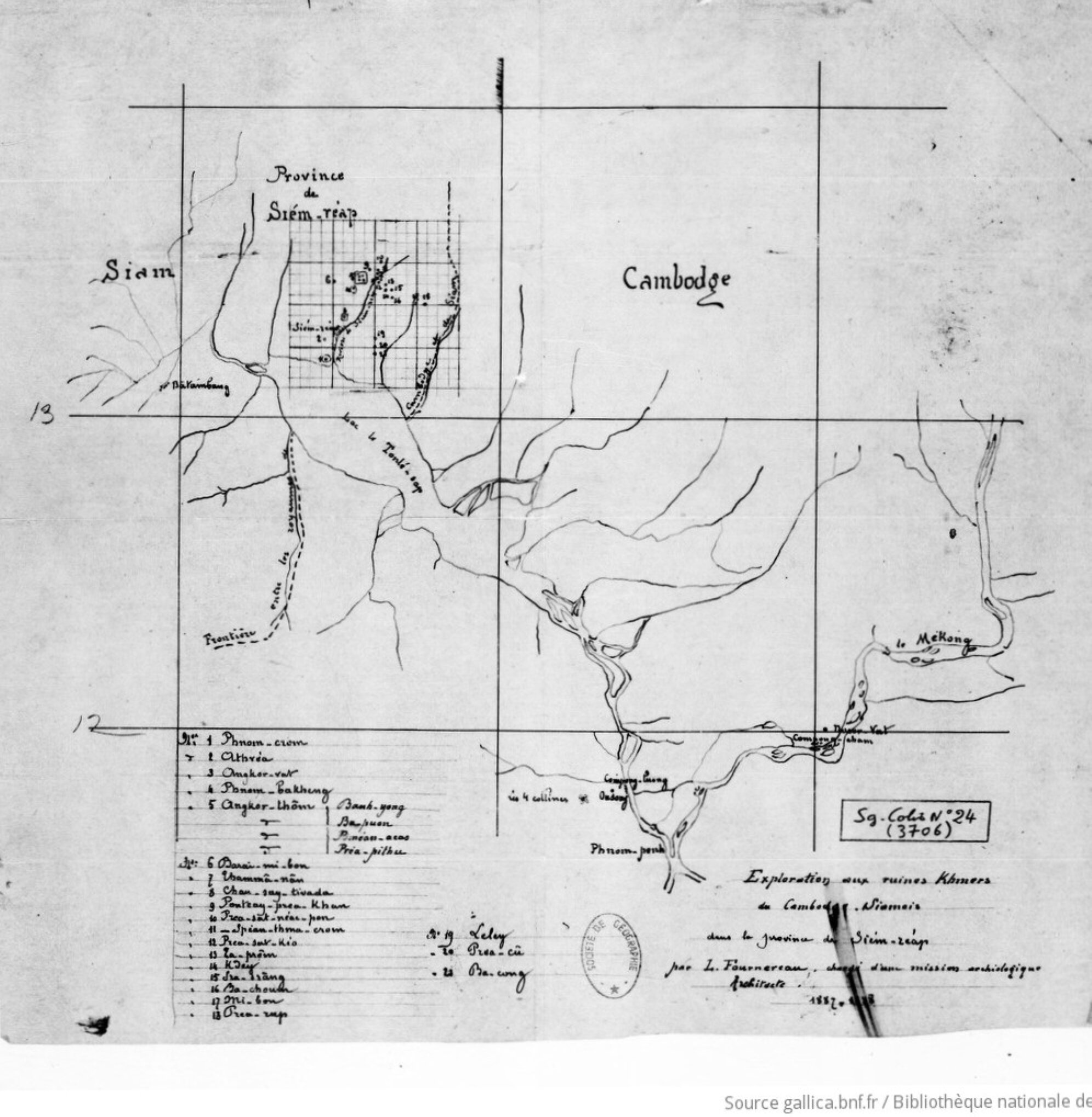

“Exploration aux ruines Khmères du Cambodge siamois”, map of the Angkor area in situation with Phnom Penh and the Great Lake. Note that Beng Maelea, right on the boundary between Siam and Cambodia before 1907, is not mentioned. [source: gallica.bnf.fr]

Publications

- Les ruines khmères du Cambodge siamois, Bulletin de la Société de géographie, vol. II, 1889.

- Les ruines d’Angkor; études artistiques et historiques sur les Monuments khmèrs du Cambodge siamois en collaboration avec Jacques Porcher, Paris, E. Leroux, 1890.

- Les ruines khmères: Cambodge et Siam, documents complémentaires d’architecture, de sculpture et de céramique; 110 planches en phototype, Paris, E. Leroux, 1890.

- “Bangkok”, Le Tour du monde, July 1894, p. 1 – 64.

- Le Siam ancien, archéologie, épigraphie, géographie, 1ere partie (tome XXVII des Annales du Musée Guimet), Paris, E. Leroux, 1895. | 2eme partie (tome XXXI des Annales du Musée Guimet), Paris, E. Leroux, 1908.

- [Gabriel Marcel, “Notice sur quelques cartes relatives au royaume de Siam”, Chap I de L. Fournereau, Le Siam ancien…, vol. I, 1895, p 1 – 44;

repr. Bulletin de Géographie historique et descriptive, 1895.] - “Les villes mortes du Siam (De Bangkok à Pak-nam phở)”, Le Tour du monde, 2eme sem. 1897, p 349 – 396.

- [tr. from FR, introduction by Walter E.J. Tips] Bangkok in 1892, by Lucien Fournereau, Bangkok: White Lotus, 1998, 171 p. ISBN13 978 – 9748434421.