Chasses au tigre et a l'éléphant: un hiver au Cambodge / A Winter in Cambodia

by Edgar Boulangier

One of the first published travel accounts from French explorers at the end of the 19th century, with hunting anecdotes and -- fortunately -- much more...

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- Alfred Mame & Fils, Tours, 1888

- Edition

- Mercure de France, 'Le Temps retrouvé', 2020.

- Published

- 1887

- Author

- Edgar Boulangier

- Pages

- 464

- ISBN

- 978-2715254053

- Language

- French

Notwithstanding some blatantly racist asides — even considering the many prejudices then in vogue –, and the usual braggadocio of a compulsive big-game hunter, this document is an important description of Cambodia at the turn of the century, more on the geopolitical level than on the ethnographic one.

The traveler was then undertaking an explorative mission for the French authorities, with the logistical support of King Norodom (who liked to refer to ‘prahok’ (fermented fish paste) as the ‘Cambodian roquefort’, according to the author).

Among his findings, we shall stress:

- some useful notations on sedimentation and erosion processes in the Mekong Basin at this time.

- a detailed description of iron ore mining and iron production in the Phnom Dek area (Kompong Thom Province). Not only the author stresses the high quality of Cambodian iron — with a minutious evaluation according to European standards — but he also describes how the Koy ethnic minority was keeping alive centuries-old techniques of extraction, production and metalwork used in Angkorian times.

- a detailed analyzis of the country’s natural resources, including precious timberwood, cotton, fruit and rice.

- the author’s personal discovery of Angkor (Part V of the book), a moment when he lowers his usual guard of ironical (and often condescending) criticisism of the ‘decadent laziness of the Khmer people’ and marks a pause, in awe before ‘this marvelous monument to human ingenuity’, ‘the utter splendor’ of the architecture and sculpture, ‘the impeccable technique’ shown by Khmer masons and sculptors.

- his collection of local legends regarding the foundation of Angkor, one of which proclaiming that the temple complex was built at a time when ‘the sea reached a position some 70 milles north of Angkor’. Dating the foundation of Angkor around the 12th century CE, and predicting that ‘the whole temple will disappear soon, being built with the crumbliest type of sandstone’, he seems to briefly overcome his blatant misogyny to note: ‘According to the Cambodian legend, the great pagoda has survived the assaults of times because it has been erected by women, which simply manifests the intrinsic gallantry of the Khmer’.

Note: whenever possible, we have added the Khmer words corresponding to their French transliteration.

The ‘Angcor River’

The author gives us a detailed roadmap of his travels through Cambodia. After stopping in Kompong Thom from Phnom Penh and heading north to the Pursat area, he went back southwards and reached Battambang. He then boated up the Sangker River to the “Great Lake”, and set sail on the lake towards the “Angcor Arroyo” (no one called it Siem Reap River then). After escaping a monsoon storm, he realized he could not go up river to the Angkorean temples:

4 février [1881] Revenus, à quatre heures de l’après-midi, à l’entrée de l’arroyo d’Angcor, nous le remontons aussi vite que le permet la fatigue de nos équipages, et vers sept heures nous atteignons un petit village; nous mouillons en face pour passer la nuit. 5 février.Dès le lendemain matin, après huit heures d’insomnie, je passé marché avec le misroc pour louer deux jonques dans lesquelles on transborde nos bagages; puis je donne congé au mandarin de Battambang, en lui remettant une lettre de remerciements pour Catatone. Il n’y a pas de charrettes dans le village maritime où nous avons accosté; je me vois donc obligé de faire à pied le voyage d’Angcor. Les Européens de Saigon le font en barque pendant la saison des hautes eaux; les jonques indigènes les prennent à l’embouchure de la rivière et les conduisent jusqu’à la ville de Siam-Rep, l’Angcor d’aujourd’hui. Mais au mois de février la navigation est interrompue par la sécheresse, et je décide que nous partirons à pied le lendemain. L’après-midi est consacré à une infructueuse tentative d’ascension de Pnom-Crôm; cette colline n’a pas 100 mètres de hauteur au-dessus de la plaine, mais les forêts noyées rendent son abord inaccessible du côté du lac; on né peut la gravir que par le nord. C’est la seconde fois que je me perds dans le dédale de ces bois, sous la conduite de guides indigènes.

6 février. Après une mauvaise nuit, je me mets en route pour Siam-Rep, capitale de la principauté, avec Hunter, Nam et deux habitants du village. J’ai confié à Sao et au boy chinois la garde de nos bagages et de nos piastres. Nous partons à pied vers huit heures, sur la lisière de jeunes bois; une digue artificielle, dont la construction remonte à l’époque des premières inondations du Grand-Lac, ou plutôt du golfe partiel- lement soumis au régime fluvial du Mékong, sert de chaussée sur un parcours de plusieurs centaines de mètres. À gauche de cette digue s’élève Pnom-Crôm, avec sa ceinture de forêts noyées; à droite s’étend une plaine inculte qui n’est plus submersible par les crues. La route contourne la montagne, et vers dix heures nous faisons halte sous un bouquet de bambous pour prendre un déjeuner sommaire. Des Cambodgiens viennent à passer, se dirigeant vers le village d’où nous venons; je les appelle, je les interroge sur la distance qui nous sépare de Siam-Rep: “Trois heures,” disent-ils.

On nous l’avait déjà dit au débarcadère, mais deux renseignements valent mieux qu’un. Seulement il s’agit de bien s’entendre sur la durée de l’heure, et je né réfléchis pas à cela sur le moment. En revanche, un scrupule me prit: j’avais confié plus de six cents dollars à un Annamite et à un Chinois; il y avait de quoi tenter l’un ou l’autre, le second surtout. Je priai donc Hunter de rebrousser chemin avec Nam et l’un de nos guides, et je déclarai que je pouvais bien faire seul une promenade de trois heures avec l’autre Cambodgien jusqu’à cette ville de Siam-Rep, dont le nom signifie littéralement “Siamois aplati”, c’est- à‑dire battu à plates coutures. Dans cette plaine, en effet, d’après les annales cambodgiennes, les Khmers ont infligé aux Siamois une défaite sanglante.

Mon plan fut exécuté, à cela près que, parti à midi, je n’arrivai à la sala de Siam-Rep qu’à sept heures du soir, dans un état d’épuisement que je n’essayerai pas de décrire. L’usage exclusif du riz, qui met à l’abri des accidents diarrhéiques, porte néanmoins une atteinte sérieuse à la santé des Européens; je marchais avec peine et dus faire des ablutions dans les trois ou quatre ruisseaux que le sentier traverse; je me reposai sous les quelques arbres qui embellissent cette plaine dénudée; enfin je livrai une vraie bataille à des vautours acharnés sur le cadavre d’un buffle, sans réussir du reste à les mettre en fuite. Mais, malgré toutes ces haltes, je n’en avais pas moins reçu pendant six heures consécutives les rayons du soleil équatorial, et cette imprudence involontaire faillit me coûter cher.

Pendant la dernière heure de marche, je né tenais plus debout, je né voyais plus clair, et aussitôt arrivé à la sala, qui se compose ici d’une grande jonque hors de service, je me couchai dans une couverture, en proie à un violent accès de fièvre. Il était temps, plus que temps, de mettre fin à ce voyage en Indo-Chine. Je le constatai non sans dépit. Dans ces crises soudaines, la créature s’insurge contre son Créateur; elle lui reproche d’avoir mis l’esprit humain, insatiable de progrès et de lumières, dans une machine dont les ressorts sont si fragiles, la durée si courte.

7 février. Ma fièvre a duré une partie de la nuit. Impossible de toucher au déjeuner que me fait servir un mandarin du palais; je reste couché dans la jonque. À cinq heures du soir, Hunter n’est pas arrivé. Huit heures d’un sommeil léthargique ont engourdi mon cerveau. Suivi de deux jeunes seigneurs qui me font de longs discours, perdus, hélas! pour la postérité, — je vais faire un tour dans la ville. Elle est bâtie sur les deux rives d’un petit arroyo non moins joli que celui de Battambang; son développement atteint 6 kilomètres; sa population dépasse sans doute 25 000 habitants. Je n’en visite que le quartier d’amont, celui qui avoisine le palais; c’est le quartier commerçant, le marché chinois. Quatre ou cinq grands magasins tenus par des Célestes étalent leurs richesses. J’achète du tabac indigène et des cigares de Manille, puis je reviens dans mon bateau, où je trouve un messager d’Hunter avec un petit mot de ce dernier. En garçon pratique, il a réclamé des voitures à Siam-Rep, et il arrivera le lendemain matin avec une partie de nos bagages. Je dîne donc tout seul, et à la cambodgienne, sous une grande tente que les mandarins ont fait dresser au bord de la rivière; ces messieurs m’accablent de questions auxquelles je né puis pas répondre. Décidément j’aurais dû rester plus longtemps à la bonzerie de Posat.

8 février. Une excellente nuit a dissipé la fatigue de mes jambes et la paralysie de mon cerveau. Un nouveau mandarin vint me voir avec une nombreuse escorte : “Balât ! balât!” me dit-il. “Ah! très bien.” Je comprends que c’est un des ministres du vice-roi, et je le vois avec plaisir déboucher une bouteille de vin de Madère que les excursionnistes de Saigon lui ont sans doute laissée comme souvenir. Venu seul, avec mon fusil sur le dos, je manqué de toute provision d’Europe depuis deux jours. Le balât me parle avec une volubilité toute méridionale, comme si je comprenais sa harangue; tantôt je réponds Nen, c’est-à-dire oui (le oui des grands seigneurs); tantôt je secoue la tête en disant Té, c’est-à-dire non. Ces réponses alternatives, faites au hasard, ont l’air de dérouter complètement mon interlocuteur. Je devine cependant qu’il parle de voitures, d’Hunter, d’Angcor-Thom; il veut dire que qu’il a envoyé des voitures a Hunter et qu on nous conduira aux ruines d Angcor.

[February 4 [1881] Returning, at four o’clock in the afternoon, at the entrance to the Angcor arroyo, we went up it as quickly as the fatigue of our crews allowed, and around seven o’clock we reached a small village; we anchor opposite to spend the night. February 5. The next morning, after eight hours of insomnia, I made a deal with the misroc to rent two junks into which we transhipped our luggage; then I bid farewell to the mandarin of Battambang, giving him a letter of thanks for Catatone. There are no carts in the maritime village where we docked; I therefore see myself forced to make the journey to Angcor on foot. Europeans from Saigon do it by boat during the high water season; the native junks take them at the mouth of the river and take them to the city of Siam-Rep, today’s Angcor. But in February the navigation was interrupted by drought, and I decided that we would leave on foot the next day. The afternoon is devoted to an unsuccessful attempt to climb Pnom-Crôm [Phnom Krom]; this hill is not 100 meters high above the plain, but the drowned forests make its approach inaccessible from the lake side; it can only be climbed from the north. This is the second time that I have gotten lost in the maze of these woods, led by native guides.

February 6. After a bad night, I set off for Siam-Rep, capital of the principality, with Hunter, Nam and two inhabitants of the village. I entrusted Sao and the Chinese boy with the care of our luggage and our piastres. We set off on foot around eight o’clock, on the edge of young woods; an artificial dike, whose construction dates back to the time of the first floods of the Great Lake, or rather of the gulf partially subjected to the flow of the Mekong, serves as a causeway over a course of several hundred meters. To the left of this dike rises Pnom-Crôm, with its belt of drowned forests; to the right extends an uncultivated plain which is no longer submersible by floods. The road goes around the mountain, and around ten o’clock we stop under a clump of bamboo to have a basic lunch. Cambodians come passing by, heading towards the village where we come from; I call them, I ask them about the distance that separates us from Siam-Rep: “Three hours,” they say.

We had already been told this at the landing stage, but two pieces of information are better than one. It’s just a matter of agreeing on the length of the hour, and I don’t think about that at the moment. On the other hand, a scruple seized me: I had entrusted more than six hundred dollars to an Annamite and a Chinese; there was reason to try one or the other, especially the second. I therefore asked Hunter to turn back with Nam and one of our guides, and I declared that I could take a three-hour walk alone with the other Cambodian to this town of Siam-Rep, whose name means literally “flattened Siamese”, that is to say beaten to the seams. In this plain, in fact, according to Cambodian annals, the Khmers inflicted a bloody defeat on the Siamese.

My plan was executed, except that, having left at noon, I did not arrive at the Siam-Rep sala until seven o’clock in the evening, in a state of exhaustion that I will not attempt to describe. The exclusive use of rice, which protects against diarrheal accidents, nevertheless seriously harms the health of Europeans; I walked with difficulty and had to perform ablutions in the three or four streams that the path crosses; I rested under the few trees which embellish this bare plain; finally I fought a real battle with fierce vultures over the corpse of a buffalo, without succeeding in putting them to flight. But, despite all these stops, I had nonetheless received the rays of the equatorial sun for six consecutive hours, and this involuntary imprudence almost cost me dearly.

During the last hour of walking, I could no longer stand, I could no longer see clearly, and as soon as I arrived at the sala, which here consists of a large junk out of service, I lay down in a blanket, prey to a violent attack of fever. It was time, more than time, to end this trip to Indo-China. I noticed this not without disappointment. In these sudden crises, the creature rebels against its Creator; she reproaches him for having put the human spirit, insatiable for progress and enlightenment, in a machine whose springs are so fragile, the duration so short.

February 7. My fever lasted part of the night. Impossible to touch the lunch sent my way by a palace mandarin; I stay lying in the junk. At five o’clock in the evening, Hunter [his English partner in previous hunting expeditions] had not arrived. Eight hours of lethargic sleep numbed my brain. Followed by two young lords who give me long speeches, lost, alas! for posterity, — I’m going to take a walk around the city. It is built on the two banks of a small arroyo no less pretty than the one in Battambang; its development reaches 6 kilometers; its population probably exceeds 25,000 inhabitants. I only visit the upstream district, the one near the palace; this is the shopping district, the Chinese market. Four or five department stores run by Celestials display their wealth. I bought some native tobacco and Manila cigars, then returned to my boat, where I found a messenger from Hunter with a little note from the latter. As a practical boy, he requested cars from Siam-Rep, and he will arrive the next morning with some of our luggage. So I dine alone, and Cambodian style, under a large tent that the mandarins had pitched on the banks of the river; These gentlemen overwhelm me with questions which I cannot answer. I definitely should have stayed longer at the Posat [Pursat] bonzerie.

February 8. A good night’s sleep took away the fatigue from my legs and the paralysis from my brain. A new mandarin came to see me with a numerous escort: “Balât! balât!” he told me. “Ah. Very good.” I understand that he is one of the viceroy’s ministers, and I see him with pleasure uncorking a bottle of Madeira wine that the Saigon excursionists have undoubtedly left him as a souvenir. Coming alone, with my rifle on my back, I have lacked any provisions from Europe for two days. The official speaks to me with a very southern volubility, as if I understood his harangue; sometimes I answer Nen, that is to say yes (the yes of the great lords); sometimes I shake my head and say Té, that is to say no. These alternative answers, given at random, seem to completely confuse my interlocutor. I guess, however, that he is talking about cars, Hunter, Angcor-Thom; he means that he has sent cars to Hunter and that they will take us to the ruins of Angcor. [Chap. XX, pp 364 – 7]

The Siamese ‘Citadel’ in Siem Reap

In the same entry, 8 Feb., the author mentioned his visit to the not-so-formidable citadel of Siem Reap, the exact location in town remaining debated to these days: a little north to present-day Street 30, where the French army established barracks from the 1920s, or much closer to Stung Siem Reap and near the historic Wat Athvea Temple ប្រាសាទវត្តអធ្វា? He took this opportunity to muse about the connections between the Battambang and Siem Reap ruling families at the time of Siamese control over the two provinces:

Après le déjeuner et la sieste, nous visitons le château du prince, ou, comme on dit, la citadelle de Siam-Rep. Entourée de petits murs, elle occupe le même espace que celle de Battambang; mais cet espace est presque désert. Chemin faisant, nous rencontrons un jeune frère du vice-roi, dont la distinction est extrême; il est le cousin du divin Apaï, mais non point son ami. Catatone ayant résolu de marier sa fille au général qui représente le roi de Siam auprès sa personne, Apaï, furieux de voir sa sœur promise à ce Siamois, qu’il déteste, essaya de lui couper le cou. Son cousin trouve le procédé un peu leste; il blâme la cruauté du futur vice-roi, auquel il prédit une triste fin, malgré la protection de l’empereur, qui a pour système, étant jeune lui-même, d’encourager les jeunes princes et d’éliminer les vieux. Mais, ajoute-t-il, les alliances entre les deux familles régnantes de Battambang et d’Angcor sont si nombreuses, qu’à vrai dire les deux principautés n’en forment qu’une seule, et la cour de Bangkok doit compter avec elles. Ce raisonnement me frappé, et j’entrevois le côté politique de la polygamie, qui permet aux familles royales ou vice-royales de devenir assez nombreuses et assez puissantes pour être à l’abri de toute tentative de dépossession.

After lunch and a siesta, we visited the prince’s castle, or, as it is called, the citadel of Siam-Rep. Surrounded by low walls, it occupies the same area as the one in Battambang; but this area is almost deserted. On the way, we met a younger brother of the viceroy, a man of extreme distinction; he was the cousin of the divine Apai, but not his friend. Catatona, having resolved to marry his daughter to the general who represented the King of Siam to him personally, Apai, furious to see his sister promised to this Siamese man, whom he detested, tried to cut off his head. His cousin found the act rather crude; he condemned the cruelty of the future viceroy, to whom he predicted a sad end, despite the protection of the emperor, who, being young himself, had a policy of encouraging young princes and eliminating the old. But, he adds, the alliances between the two ruling families of Battambang and Angcor are so numerous that, in reality, the two principalities are essentially one, and the court in Bangkok must reckon with them. This reasoning strikes me, and I glimpse the political aspect of polygamy, which allows royal or viceregal families to become numerous and powerful enough to be immune to any attempt at dispossession. [p 347]

Founding Legends of Angkor

The following testimony gives an account of the state of Angkor Wat at the time (and its temptative datation), of the (awkward) attempts at restoration by the Siamese authorities, and of the numerous legends surrounding the temples in the locals lore:

10 février. La question de l’ancienneté de ce temple n’est pas élucidée encore. Les inscriptions qui couvrent ses murs sont bien tracées en caractères semblables à ceux du cambodgien moderne; aucun lettré, que je sache, n’a pu parvenir encore à les déchiffrer. J’interroge les bonzes et mon vieux guide de Siam-Rep, mais je né recueille que des réponses confuses ou contradictoires. “Il y a 2 400 ans, disent-ils, qu’Angcor fut abandonnée par ses habitants.” Puis ils ajoutent: “Il y a dix-huit siècles, la mer s’étendait à 70 milles au nord d’Angcor, jusqu’aux montagnes de Srei-Srano, près des ruines de Korat.” Comment admettre qu’Angcor ait existé au milieu des eaux, à 70 milles du rivage? Si elle eût été bâtie au sommet d’un haut plateau, passé encore; mais la plaine qui l’entoure est presque au même niveau que le fond du Grand-Lac actuel. Mes Cambodgiens en conviennent, et, poussé à bout, le guide finit par dire: La construction de la pagode remonte à douze siècles.. À la bonne heure! voilà une date qui concorde mieux avec les données hydrologiques d’après lesquelles la formation du Grand-Lac et la submersion de ses rives remontent à six siècles tout au plus. Encore cette date est-elle trop éloignée; le voyageur chinois qui visita l’empire khmer en 1295 et décrivit ses monuments avec une grande minutie, né dit pas un mot d’Angcor-Wat. La pagode n’a donc pas plus de six cents ans d’existence. Du reste, quand on voit de quelle pierre tendre la femme du Roi Lépreux a fait construire le tombeau de son époux, quand on a remarqué que ce grès calcaire, altérable par les alternatives de sécheresse et d’humidité, est tellement friable, qu’il s’effrite à l’ongle [1], on se convainc de la jeunesse relative de ce monument, dont la partie centrale, la plus destructible, est encore si bien conservée. Il né faudrait donc pas s’étonner si l’épi- graphie le rajeunissait encore d’un siècle, et peut-être davantage. À coup sûr, Angcor-Wat est de beaucoup postérieur à toutes les ruines de la région; c’est le dernier chef-d’œuvre d’une civilisation très avan- cée, et la légende cambodgienne, d’après laquelle la grande pagode a résisté aux injures du temps parce qu’elle a été construite par des femmes, prouve simplement la galanterie des Khmers.

[1] Les Cambodgiens l’appellent ina-phoc, pierre de boue [puzzling transliteration, as ‘sandstone’ in modern Khmer is ថ្មភក់, thmaupkh]. Les Siamois ont fait quelques travaux de restauration, mais fort inintelligents. Des colonnes rondes ont été placées, le chapi-teau en bas, au milieu de colonnes carrées; les architraves ont été retournées sens dessus dessous, etc.

[February 10. The question of the antiquity of this temple is still wanting clarification. The inscriptions which cover its walls are well traced in characters similar to those of modern Cambodian; no scholar, that I know of, has yet been able to decipher them. I question the monks and my old guide from Siam-Rep, but I only receive confused or contradictory answers. “2,400 years ago,” they say, “Angcor was abandoned by its inhabitants.” Then they add: “Eighteen centuries ago the sea extended 70 miles north of Angcor, to the mountains of Srei-Srano, near the ruins of Korat.” How can we admit that Angcor existed in the middle of the waters, 70 miles from the shore? If it had been built on the top of a high plateau, it still happens; but the plain which surrounds it is almost at the same level as the bottom of the current Grand Lake. My Cambodians agree, and, pushed to the limit, the guide ends up saying: The construction of the pagoda dates back twelve centuries.. Good timing! here is a date which agrees better with the hydrological data according to which the formation of the Great Lake and the submersion of its banks date back six centuries at most. This date is still too far away; the Chinese traveler who visited the Khmer empire in 1295 and described its monuments with great detail [Zhou Daguan], did not say a word about Angcor-Wat. The pagoda is therefore not more than six hundred years old. Moreover, when we see from what soft stone the wife of the Leper King had her husband’s tomb built, when we notice that this calcareous sandstone, alterable by the alternations of dryness and humidity, is so friable, that it crumbles under your fingernail [1], we are convinced of the relative youth of this monument, the central part of which, the most destructible, is still so well preserved. We should therefore not be surprised if epigraphy made him younger by another century, and perhaps more. Certainly, Angcor-Wat is much later than all the ruins in the region; it is the last masterpiece of a very advanced civilization, and the Cambodian legend, according to which the great pagoda resisted the ravages of time because it was built by women, simply proves the gallantry of the Khmers.

[1] The Cambodians call it ina-phoc, mud stone [puzzling transliteration, as ‘sandstone’ in modern Khmer is ថ្មភក់, thmaupkh]. The Siamese have done some restoration work, but in a very unintelligent way. Round columns were placed, the capital at the bottom, in the middle of square columns; the architraves have been turned upside down, etc. [Chap. XIII, pp 373 – 5]

Photo: The second edition of Un hiver au Cambodge, 1888.

Tags: travelogue, French explorers, Norodom I, wildlife, iron, Khmer architecture, women, Tonle Sap, hydrology, Siem Reap River, Steung Siem Reap, Kuy people, legends, Siamese occupation, Queen Mother Monineath, Phnom Krom, Siem Reap Citadel

About the Author

Edgar Boulangier

French civil engineer, indefatigable traveler and compulsive big-game hunter Marie Auguste Edgar Boulangier (1850−1899) visited Cambodia in 1880 – 1881, his first official mission for which he was granted logistical support by King Norodom. This ‘mineralogical-hydrological’ exploration was supposed to evaluate Cambodia’s natural resources after the establishment of the French Protectorate (ប្រទេសកម្ពុជាក្រោមអាណានិគមបារាំង) in 1863.

An ingénieur des Ponts-et-Chaussées, he published his first book in 1887, a travelogue entitled Chasses au tigre et à l’éléphant: Un hiver au Cambodge (Tours, France, 2d edition 1888) in which he stressed the potential for iron ore and gold extraction, intensive agriculture and commercial exchanges in Cambodia, and offered a rare description of Angkor.

After Indo-China, Boulangier was sent to Subsaharian Africa, Central Asia and Siberia, mostly to study railway transportation and infrastructure development.

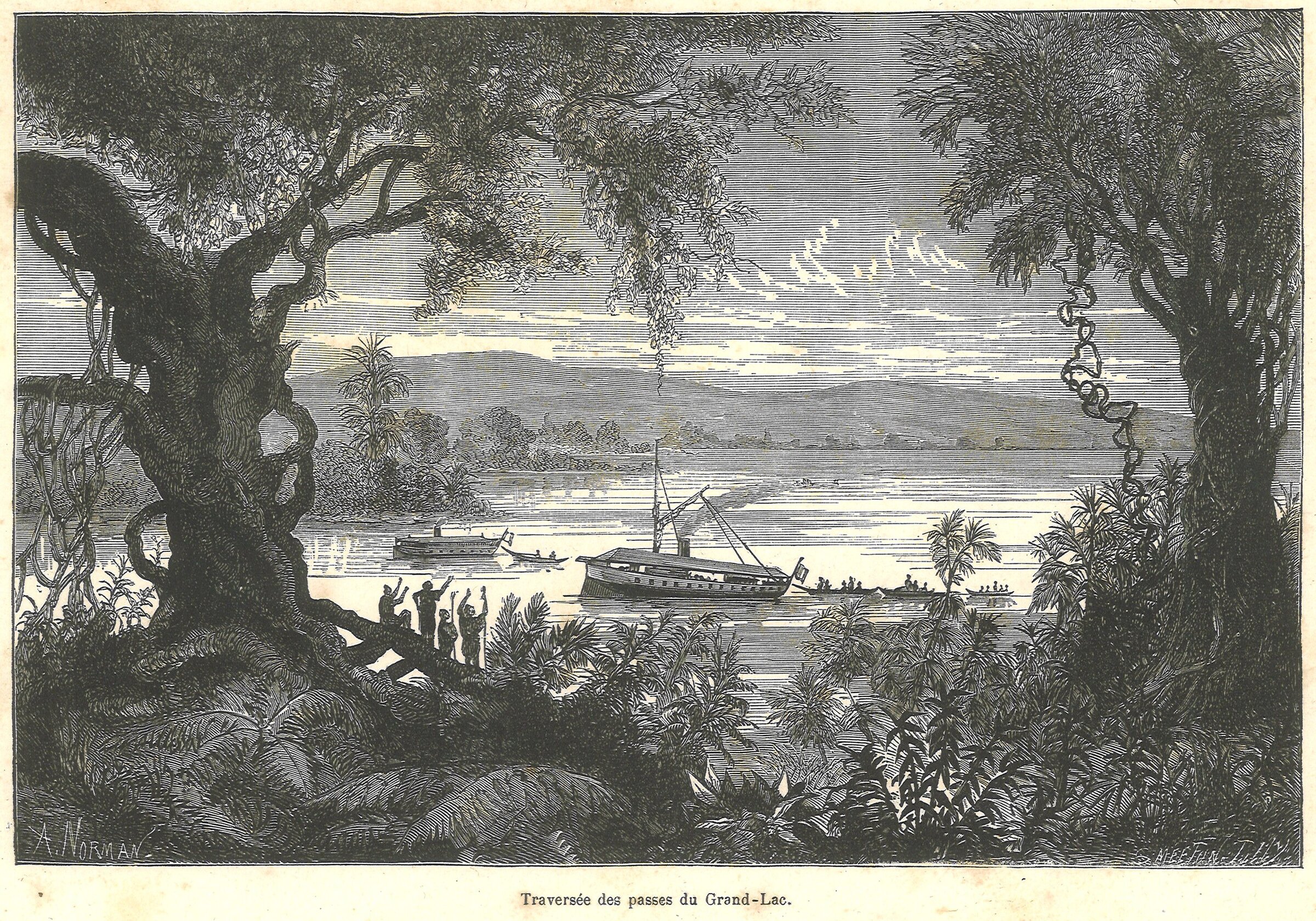

“Entering the channels of Tonle Sap Lake”, illustration in Un hiver au Cambodge, 2d ed., 1888.

Publications

- “Communication à la Société géographique de Paris sur son voyage au Cambodge”, Revue L’Exploration, II, 1881.

- “Le lac du Cambodge”, Revue scientifique, 26 fév. 1881, [compte-rendu] Bulletin Société maritime et coloniale, mars 1881.

- “Les mines de fer de Compong Soai au Cambodge”, Excursions et Reconnaissances n° 10, 1881, 7p.

- “Chasses au Cambodge”, Gazette des Bains de mer de Royan, juillet-août 1881.

- “Correspondance avec Aymonier”, Journal officiel de la Cochinchine, 1881.

- Le débit du Mékhong, Saigon, in 8.

- “La colonisation de l’Indochine”, Revue maritime et coloniale, 1885.

- Un hiver au Cambodge: chasse au tigre, à l’éléphant et au buffle sauvage. Souvenirs d’une mission officielle en 1880 – 1881, Paris, 1887; augmented edition, Tours, Alfred Mame & Fils, 1888, 400 p. with illustrations; repr. Paris, Mercure de France, 2020, 464 p.