Kingdom in the Morning Mist: Mayréna in the highlands of Vietnam

by Gerald Cannon Hickey

A contextualized portait of the "dashing and enigmatic Frenchman" who founded the Sedang Kingdom among the Highland tribes of Vietnam in 1888

Type: hardback

Publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press

Published: 1988

Author: Gerald Cannon Hickey

Pages: 221

ISBN: 0-8122-8106-3

Language : English

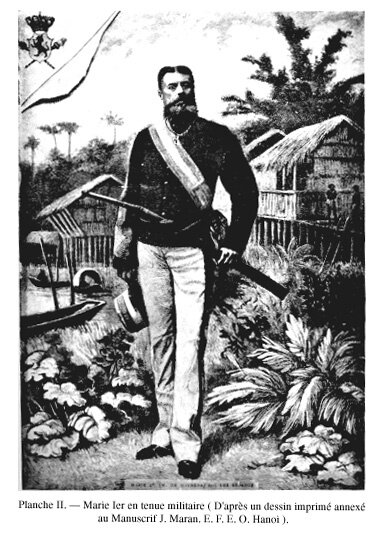

ADB Library Catalog ID: HISMONT1

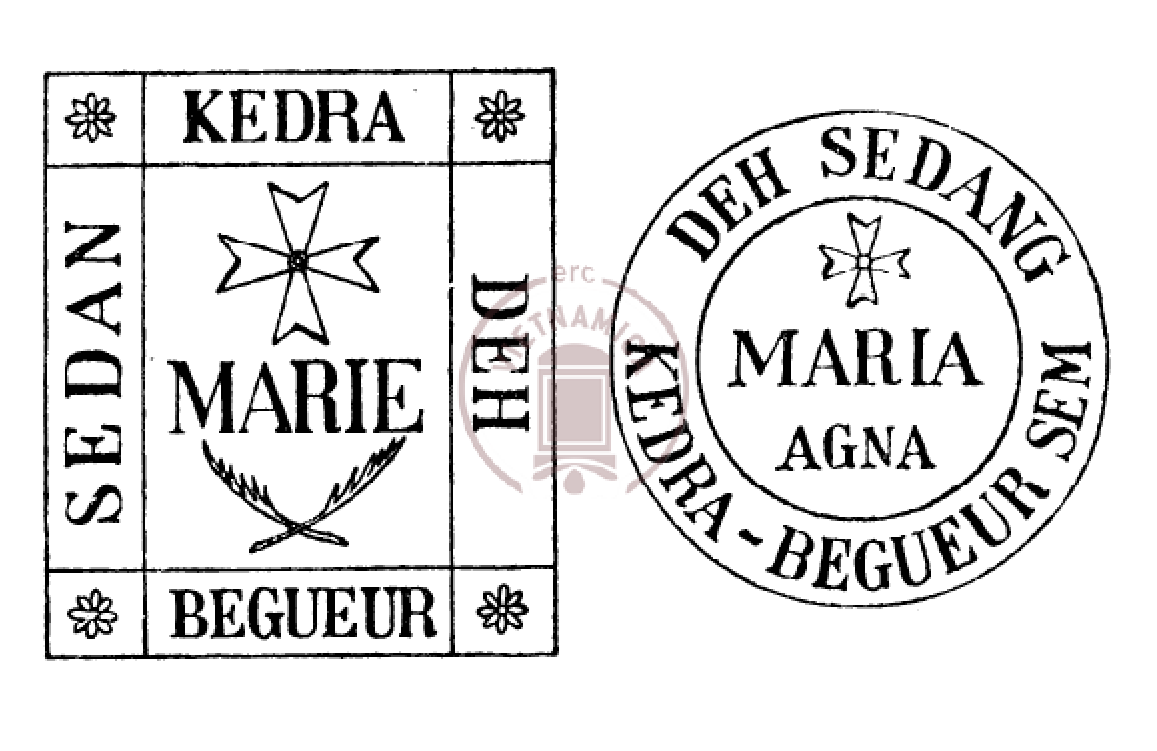

Born Auguste-Jean-Baptiste-Marie-Charles David on 31 January 1842 in Toulon, Var, France, the 1.82 m tall adventurer who was to become (briefly) the King of the Sedangs in 1888 bore the names of David-Mayréna, Charles de Mayréna, David de Mayréna, baron de Mayréna, and finally King Marie I before dying mysteriously (snake bite or suicide), on 11 November 1890 at 3:30 PM, in a remote hut he had built on the Malay west coast, in Kuala Rumpin, near Pulau Tioman (Tioman Island).

The life of Mayréna (1842−1890), “modern conquistador, swindler and loser”, had been studied in detail by Jean Marquet in 1927, in the Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hué [v 12, 14th year, Jan-July 1927, 141 p. In French. via Vietnamica.online), in which we learn that, among his many attempts to obtain monies and favors across the region (Atjeh (Aceh), Singapore, and of course the Vietnamese highlands), Mayréna went to Cambodia in 1887, where “assisté de Mercurol, agent des Contributions Indirectes en permission, qui sert d’interprète, Mayréna propose tout simplement à Norodom la création d’une compagnie de navigation fluviale royale.… David de Mayréna, toujours modeste, se contenterait du titre de Grand Ecuyer de Sa Majesté ! (Lettre du Résident Général au Lieutenant-Gouverneur, 29 Novembre 1887). Le roi du Cambodge né daigna sans doute pas donner crédit à des propositions pourtant si brillantes, car nous retrouvons [bientot] Mayréna en Cochinchine.” [“assisted by Mercurol, a tax inspector on leave, who serves as interpreter, Mayréna quite simply proposes to King Norodom the creation of a Royal River Navigation Company.… David de Mayréna, always modest, would content himself with the title of Grand Equerry of His Majesty! (Letter from the Resident General to the Lieutenant-Governor, November 29, 1887). The King of Cambodia probably did not deign to give credit to such brilliant proposals, because we [soon] find Mayrena in Cochinchina.”

“Fascinating yet sad anti-hero” according to André Malraux, Mayréna was however one of the first “colons” to foresee the potential of latex cultivation and, if we give some credit to the lengthy piece Marcel Ner devoted to the character in the respected Bulletin de l’Ecole Francaise de l’Extreme Orient (“Jean Marquet : Un aventurier du XIXe siècle. Marie 1er, roi des Sédangs, 1888 – 1890; Maurice Soulié : Marie Ier,roi des Sédangs, 1888 – 1890”, BEFEO 27, 1928, p. 308 – 50), could have been instrumental in resisting the English-Siamese penetration of Annam-Cochinchina in the 1880s: “Mayréna signale dans son rapport un fait moins dramatique [que sa supposée contribution dans la lutte contre les Prussiens en France en 1870], mais plus dangereux: le voyage de deux Anglais. C’est là qu’était le véritable danger. Après la chute de Jules Ferry (30 mars 1885), l’Angleterre avait hâtivement mis à profit les hésitations de notre politique coloniale. Le Vice-roi des Indes avait, le Ier décembre 1885, signé le traité qui lui assurait la possession de la Haute Birmanie. L’état tampon dont avait rêvé J. Ferry disparaissait ainsi. Nos voisins poussaient le Siam à s’étendre vers le Mékong et même à le déborder. Les Siamois avaient envoyé une expédition dans les régions de Luang Prabang et du Trân-ninh. Plus au Sud, ils avaient profité de la révolte des lettrés pour pénétrer sur la rive gauche du Grand Fleuve et prétendaient fixer la frontière à la ligne de partage des eaux Annam-Mékong. En 1887, ils s’étaient installés sur la moyenne Sé-san, avaient occupé de façon permanente Attopeu, Saravan, Siempong. On voyait se réaliser les prophéties de Paul Deschanel, qui écrivait en 1885 : “Le jour où

l’Angleterre prendra la Birmanie, notre autorité dans la partie orientale de la presqu’île indochinoise subira une réelle atteinte.” Des hommes comme M. de Kergaradec, notre consul à Bangkok, M. Lemire, Résident de Qui-nhon, signalaient le danger de ces empiétements.” [“Mayréna points out in his report a less dramatic fact [than his supposed contribution in the fight against the Prussians in France in 1870], but more dangerous: the journey of two Englishmen. This is where the real danger was. After the fall of Jules Ferry (March 30, 1885), England had hastily taken advantage of the hesitations of our colonial policy. The Viceroy of India had, on December 1, 1885, signed the treaty which assured him possession of Upper Burma The buffer state that J. Ferry had dreamed of thus disappeared. Our neighbors pushed Siam to expand towards the Mekong and even to overflow it. The Siamese had sent an expedition to the regions of Luang Prabang and Trân-ninh. Further south, they had taken advantage of the scholarly revolt to penetrate the left bank of the Great River and claimed to set the border at the Annam-Mekong watershed. In 1887, they had settled on the middle Se- san, had permanently occupied Attopeu, Saravan, Siempong. We saw the prophecies of Paul Deschanel come true, who wrote in 1885: “The day when England will take Burma, our authority in the eastern part of the Indochinese peninsula will suffer a real attack.” Men like Mr. de Kergaradec, our consul in Bangkok, Mr. Lemire, Resident of Qui-nhon, pointed out the danger of these encroachments.”

So, was he a strategic visionary or a desperate, rogue swashbuckler, and a womanizer to boot, a trait that was much frowned upon by the prudish French colonial administrators of the time? Married in Toulon on 3 March 1869 to Maria Francisca Avron, a daughter of Martial Louis Marie Avron and Rosalie Cécile Célestine Baron, we find the protoganist of this biography in 1885 Saigon haunting Rue Catinat cafes and the theater (then ran by his brother) “always accompanied by an exotically beautiful woman, whom he introduced as Anahia, claiming she was a princess of the royal line of Cham rulers.” [she was the daughter of a simple woodcutter, notes the author.] And during his short ‘reign’, and later on his exile to Malaysia, he was rumored to have numerous concubines. The biographer tends to surmise he was no ugly macho, though: “He went on his way, experiencing new adventures and sampling more of l’amour.” (p 178) Note that the coastal city of Quy Nhon, from which Mayréna started his expeditions to the highland and the Sedang country, is close to the site of the ancient Cham city of Vijaya, and some of his discoveries about the Cham civilization was later considered with interest by EFEO.

One element that we find not considered thoroughly enough in this study is the nefarious role of Catholic missionaries in the highlands. In his paper ‘Beyond Complicity and Naiveté, Contextualizing the Ethnography

of Vietnam’s Central Highlanders 1850 – 1990’, Oscar Salemink notes: “The involvement of the missionaries was evident in all three major events taking place in the Highlands during the last two decades of the century. During the ‘Revolt of the Literati’ (1885−1888), an early expression of Vietnamese resistance against the French occupation of Tonkin and Annam, Catholics were targets of the movement, because they often acted as a fifth column for the French. During the Mayréna Affair (1888−1890), the Belgian adventurer Mayréna, charged with an official mission to counter Siamese (British, German) influence in the Highlands, relied on support from the missionaries of Kontum to found a ‘Sedang Kingdom’, expecting the auriferous rivers in Sedang country to be highly profitable. After official disavowal by the colonial authorities, Mayréna was denied further access to ‘French’ Indochina. [Father ] Guerlach then brought his ‘Bahnar-Rengao Confederation’ under nominal Vietnamese authority, even when Siamese military columns tried to enforce Siamese claims of Laos and the Highlands. During the expedition of the ‘Mission Pavie’ (1890−1893), installed to secure Laos and the left bank of the Mekong river for France, Kontum functioned as the base area for military expeditions by the captains Cupet and De Malglaive. All three events were related to the claims that France developed to the territory east of the Mekong. These claims were upheld in the face of the Vietnamese struggle to remain independent, and of Siamese efforts to extend their influence eastward towards the South China Sea, by and large following the Annam Cordillera (Chaîne Annamitique or Truong Son) in the eastern part of the Highlands. The French considered the Mekong River to be a secure border against any British or German schemes rather than a viable transport route.

Already in the 1860s, the great ‘Mekong Expedition’ of Doudart de Lagrée and Francis Garnier proved that the Mekong was not a viable route to southern China, which shifted French colonial interest to the Red River in Tonkin as a possible commercial artery. Although there is much talk of ethnographic study in the reports, not much more is done than noting the existence of indigenous populations.[…] Resident Guiomar of Qui-Nhon [was sent] to Kontum in order to liquidate the kingdom (which had been a legal fiction anyway, as the Montagnards themselves were hardly involved). Guiomar, however, was far from convinced of the patriotism which allegedly motivated the missionaries’ actions: “The missionaries consider the country which they occupy as their property and they

never willingly encourage any European at all to settle there. […] After first dreaming of founding a free state like that of the Jesuits in Paraguay and thinking that they found in Mayréna a pliable instrument who would be entirely at their disposal, they soon discovered their mistake and found that he had an appetite for independence. So they preferred to abandon their projects rather than find themselves subordinated to a master. This business has nothing to do with Patriotism.” The missionaries made up for their mistake by putting their ‘Bahnar-Reungao Confederation’ formally under French authority.”

Back to the here reviewed book, the author’s most notable contribution is to assess the post-colonial status of Vietnamese ethnic minorities, their involvment in the independence struggle. He gives us important information about Nay Luett, a Jarai who was appointed in June 1971 Minister for ethnic minorities’development, and whose wife was a descendant of the famous Jarai chef Nay Nui, about his secretary generel Touneh Han Tho, a Chru leader, and about Pierre K’Briuh, his director general and a son of a Sre chief. Then, after a terrible war waged by France and then the US, a sorrowful, ‘inescapable’ conclusion: “The highland people, their way of life, and their world are passing into that strange twilight between zero and infinity.”

Based in Cambodia, the travel agency Amica Travel offers a “Sur les traces de David Mayréna” [In the footsteps of David Mayrena] 7circuit across the Vietnamese highlands.

Tags: French colonialism, ethnic minorities, Jarai, Highlands, Vietnam, Vietnam War, French explorers, Chams, missionaries

About the Author

Gerald Cannon Hickey

Gerald Cannon Hickey (17 Dec. 1925- 10 Nov. 2010, Chicago, IL, USA) was an anthropologist who worked in Southeast Asia, primarily Vietnam. From 1956 through 1973, he conducted ethnographic research in Vietnam; during the 1960s his research was sponsored by the RAND Corporation. He built ties with many of the tribes of South Vietnam and wrote several books (including A Village in Vietnam (Yale University Press, 1964), Free in the Forest, Sons of the Mountains, Shattered World) on the people living in Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

The presentation of his Window on a War: An Anthropologist in the Vietnam Conflict (Texas Tech University, 2002) states that “when Gerald Hickey went to Vietnam in 1956 to complete his Ph.D. in anthropology, he didn’t realize he would be there for most of the next eighteen years — through the entire Vietnam War. After working with the country folk of the Mekong Delta for several years, in 1963 Hickey was recruited by the RAND Corporation, which was contracted by the U.S. government to study and report on the highland tribes. He lived through the Viet Cong night attack on the Nam Dong Special Forces Camp in July 1964, and he survived the full-scale battle at Ban Me Thuot during Tet, 1968. Worst, he witnessed the decline of the mountain people from proud highlanders to refugees from a war none of them wanted and few understood.”

A collection of 16 Hickey’s photographs of Montagnard people in Vietnam (1960−9), mostly Jarai, Jeh and Stieng, is kept at The Smithsonian Institution (NAA.PhotoLot.73 – 34).