One Hundred Years of Solipsism: The Malraux Case Revisited

by Angkor Database

One century later, André Malraux's raid on Banteay Srei bas-reliefs is still raising interest and controversy.

- Publication

- ADB Research Document BSMAL1

- Published

- 2023

- Author

- Angkor Database

- Languages

- English, French

December 2023: while musing around Banteay Srei precious pavilions bathed in the golden light of late afternoon, one cannot resist eavesdrop on two Cambodian professional guides standing before the gracious devatas ripped off their alcoves by André Malraux (1901−1976) and his childhood friend Louis Chevasson on 22 December 1923. One addresses a small group of visitors in Spanish, the other in English, and none of them even mention the deplorable fate they briefly suffered. Reinstated in 1925, they smile to the trees far away and to a Cambodian future in which bad karma has no place.

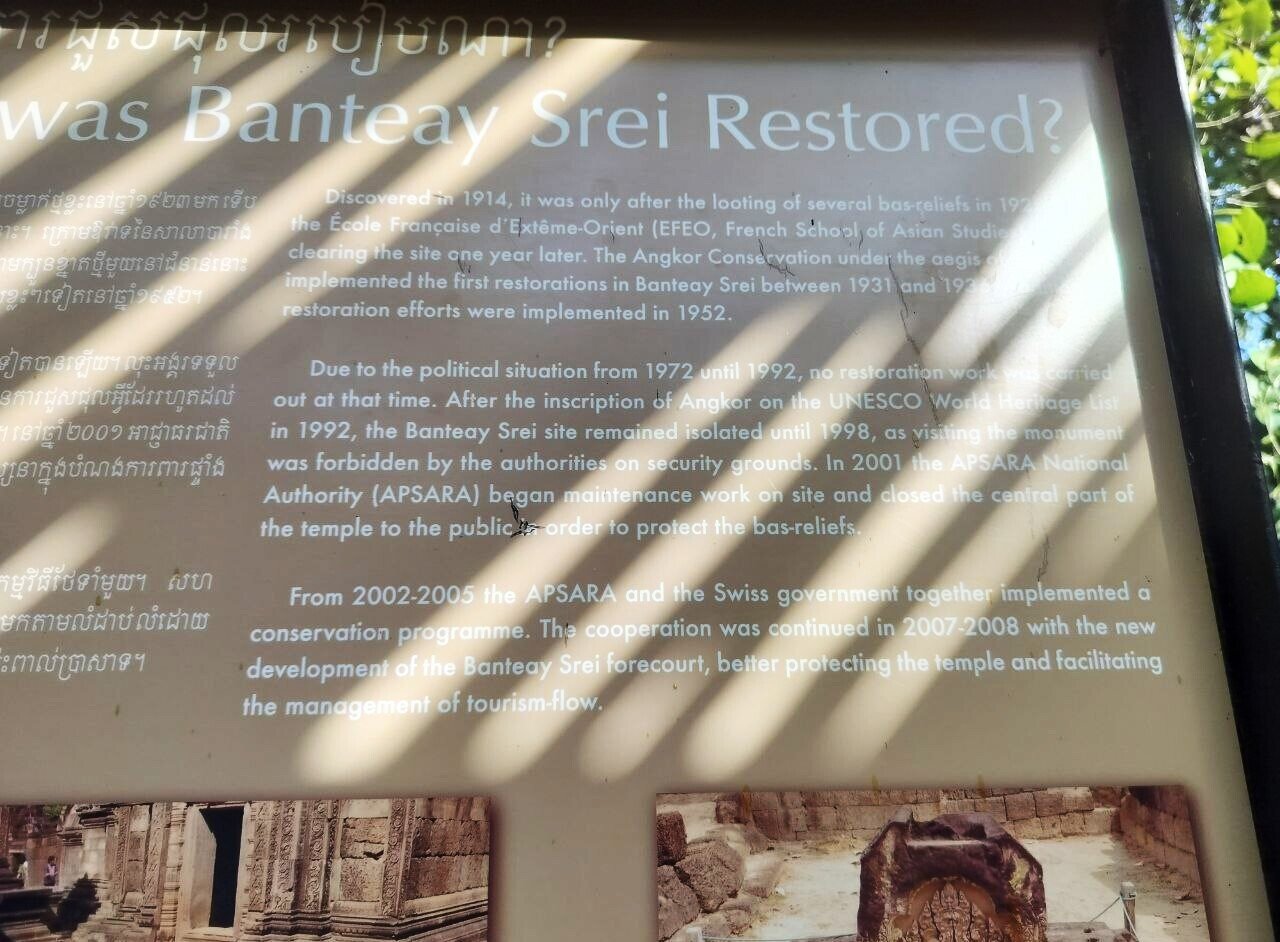

The directory panel set by Apsara Authority at the entrance of Banteay Srei soberly mentions that “discovered in 1914, it was only after the looting of seven bas-reliefs in 1923 that EFEO started clearing the site one year later.”

Back to 1923: The Guimet Museum Society of Friends (SAMG) is launched, after the museum’s foundation in 1889 by industrialist and art collector Émile Guimet (1836−1918). Its reading hall, a magnet for young Parisians fascinated with Asian art, gives access to reference works such as L’inventaire des monuments du Cambodge (1911) by Lunet de Lajonquiere, Voyage au Cambodge by Louis Delaporte, Aymonier’s studies, and the collection of Bulletin de l’EFEO, in which Henri Parmentier has published in 1919 his detailed work on several temples (Bakong, Prasat Phnom Krom, Roluos group…) including one newly rediscovered, fascinating, Khmer temple, Banteay Srei: L’Art d’Indravarman (Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient. Tome 19, 1919. pp. 1 – 98).

Among those readers were André and Clara Malraux (22 Oct 1897 — 15 Dec 1982, née Goldschmidt, they had married against the will of Clara’s family in 1921), and the latter will note in her memoirs: “I had browsed the inventory of Khmer monuments…Oh well, we will go to some small temple in Cambodia, take a few statues, sell them in America and live comfortably for two or three years ….” (in Le bruit de nos pas. II: Nos vingt ans: 1966, p. 112).

1923 is also the year when Joseph Hackin (8 Nov 1886, Boevange-sur-Attert, Luxembourg – 24 February 1941, at sea near Faroe Islands) became the Musée Guimet curator. Author of the first compilation of Buddhist Art at the museum, and set to explore the Bamyan site in Afghanistan in 1924 with Alfred Foucher and André Godard, Hackin, a renowned archaeologist and one of the first to join the French Resistance in 1940, trusted Malraux’s apparently laudable interest in Khmer art, and felt “betrayed” when the Banteay Srei scandal happened (see Régis Koetschet, A Kaboul revait mon pere: André Malraux en Afghanistan, Nevicata, Brussels, 2021, ISBN 978−2−87723−174−1)

It has been said that the young couple also learnt about Khmer art from art historian, curator and sinologist Alfred Salmony (10 Nov 1890, Köln, Germany — 29. April 1958, near Paris, France), who was to publish his essay Sculpture in Siam in 1925. In 1938, Salmony was teaching at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. It is obvious that Salmony never encouraged Malraux to go do his shopping in Banteay Srei, but his influence can be seen years later, when the soon-to-be Minister of Cultural Affairs of France was developing his concept of “musée imaginaire” (museum without walls) by cropping and rearranging photographs of artworks in order to “decontextualise art in order to express its universality.” “Malraux embraced the potentialities of the use of photography in art history and, borrowing from Alfred Salmony, assistant curator at the Cologne museum, he effectively used the methodology of making epochal stylistic comparisons with images,” writes Clarissa Ricci in “The Atlas as Method: The Museum in the Age of Image Distribution” (communication to OPEN ARTS symposium, University of Bologna, 20 – 21 April 2021).

Yet, as Michael Freeman remarked in his 2004 travel book around Cambodia [Cambodia (Topographics), Reaktion Books, 2004 & 2012] “officially sanctioned looting played its part, and in the case of Cambodia helped to found the great Musée Guimet in Paris. The inspiration for this came from the colonial competition between the British and the French. Having established a protectorate over Cambodia in 1864, the French mounted an expedition to the Mekong river, the prize being a trade route to China. It was led by the French representative in Cambodia, Doudart de Lagrée, in 1866, and among its many investigations were the ruins at Angkor. Inspired by this, one of its members, Louis Delaporte, returned in 1873 with his own expedition to collect the finest statues. These, in 1882, became the core of the collection of the Musée Indochinois de Trocadéro in Paris, and eventually, in 1927, of the Musée Guimet.”

As the Latchford saga and the rapid pace of looted Khmer art restitution have been unfolding in recent years, Malraux’s 1923 raid on Banteay Srei brings us back to a time when, even for supposedly anti-colonialists, the idea that Khmer heritage could be used at one’s will was still common, and must be seen as it was: a brazen attempt in cultural reappropriation for mercantile motives.

The Facts

At the time of the theft, André Malraux had met in Hanoi EFEO’s Léonard Aurousseau, a scholar more absorbed in the study of Chinese and Vietnamese manuscripts than in fieldwork around Angkor, who insisted that all objects discovered in the course of projected excavations, must remain in situ. Aurousseau, portrayed as an ageing, old-school penpusher in the Royal Way, was at the time engaged in a quite ferocious controversy with Henri Maspero and other researchers around the origins of Annamite people.

He passed Malraux’s petition for researching Khmer temples onto Henri Parmentier, whose indulgence towards the culprits in the 1924 trials remains puzzling. Our guess is that Parmentier, dazzled by the glibness of the young Clara-André couple, never suspected they were aiming at Banteay Srei. And he had a personal hesitation about this particular site, too: Georges Démasur (4 June 1887, Paris 18, France — 2 May 1915, Seddhul Bahr (Dardanelles Straits), Turkey), the one who had factually documented Banteay Srei for the first time in 1914 after being tipped by cartographer and explorer Jules Marec (and was killed in World War I one year later), had been Parmentier’s protégé Maurice Glaize’s direct rival in the selection exam to enter EFEO in 1913.

But while EFEO heavyweights were surprisingly lenient towards Malraux’s desecration of a 10th-century Khmer temple, the man who really stopped the looting attempt was George Groslier. As Kent Davis remarks in his Groslier’s biographical essay, ‘Le Khmerophile: The Art and Life of George Groslier’ (in Cambodian Dancers by g. Groslier, English translation, DATAsia, 2011), “in Cambodia, his attempted cultural theft was of such magnitude that it permanently scarred his reputation. Upon hearing Malraux’s name, Nicole Groslier instantly remembered hearing of her father’s encounter with “le petit voleur” (the little thief). The Franco-Khmer writer Makhali-Phal called him by the same name in her papers and, when introduced to him in Paris in the 1930s, refused to shake his hand.” (pp71‑2) When he had met André and Clara in Phnom Penh, taking them to a Musee Albert-Sarraut (now National Museum of Cambodia) visit, Groslier was the first to see through Malraux’s hidden agenda: “L’impression que m’avait produite M. Malraux lors de son passage à Phnom Penh, et bien qu’il me fût présenté par M. Parmentier, avait été défavorable. Il se montra trop au courant de l’art khmer envisagé par un antiquaire, notamment des têtes khmères de provenance mystérieuses mises en vente chez Bing, rue Saint-Georges à Paris, à des prix fabuleux”. [“The impression that Mr. Malraux had left on me during his visit to Phnom Penh, although he was introduced to me by Mr. Parmentier, had been unfavorable. He came across as too familiar with Khmer art seen by an antique dealer, in particular Khmer heads of mysterious provenance put on sale at [Galerie] Bing, rue Saint-Georges in Paris, at extravagant prices.”]

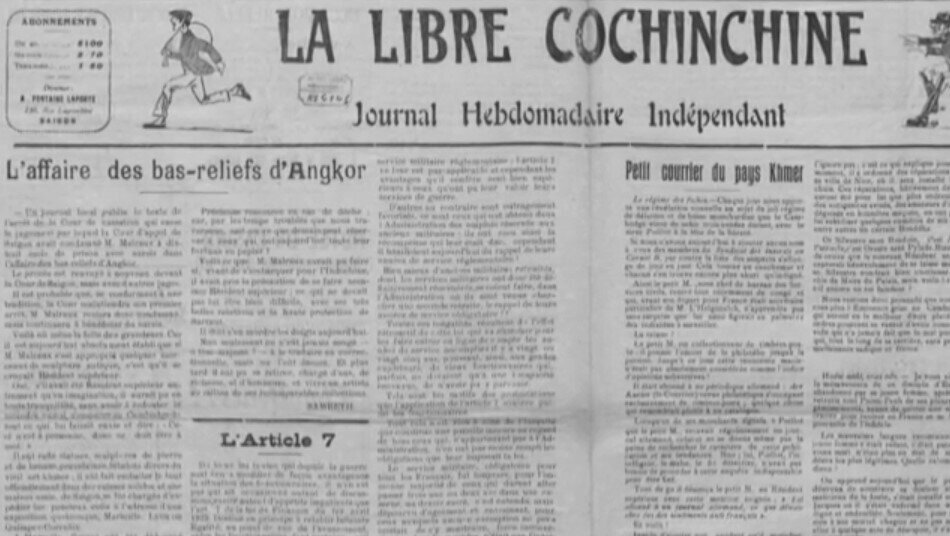

In continuation, we publish press dispatches related to the Malraux-Chevasson trial in Phnom Penh:

Angkor: Les pillages Chevasson et Malraux (Les Annales coloniales, 28 Feb 1924): “Notre confrère l’Écho du Cambodge nous apprend que les amateurs d’antiquités commencent à se livrer au pillage des ruines d’Angkor dans les conditions qu’il expose ainsi qu’il suit : Le juge d’instruction de Pnom-Penh est saisi d’une affaire qui s’est déroulée il y a une quinzaine de jours et dans laquelle sont inculpés deux Européens arrivés récemment de France dans le but de visiter les ruines d’Angkor et, par la même occasion, emporter quelques souvenirs qui auraient, et bien au-delà, remboursé le prix de leur voyage. Des renseignements de source autorisée nous permettent aujourd’hui de donner des détails précis sur cet acte de pillage qui dénote, de la part des auteurs, une audace inouïe et des connaissances particulières de la valeur des sculptures volées. L’enquête a révélé qu’un certain M. C. [Louis Chevasson], venant de France, arrivait à Saïgon où il rencontrait M. M. [André Malraux], également arrivé d’Europe par un courrier précédent. Anciens camarades de collège, ils décidèrent de visiter, de compagnie, les ruines d’Angkor. Ils entreprirent donc le voyage ensemble jusqu’à Pnom-Penh où ils se séparèrent l’intervalle d’un courrier pour se retrouver à Siem-Réap quelques jours plus tard. Leur séjour à Angkor fut remarqué par l’intérêt particulier qu’ils portaient à la visite du temple non restauré de Bantheai-Say [sic, Banteay-Srei], situé à 25 kilomètres d’Angkor, généralement dédaigné par les touristes. Mais ce qui contribua le plus à attirer l’attention sur leur attitude, c’est qu’au lieu de se faire conduire sur les lieux par la moderne auto, ils préféraient la charrette à boeufs. Cela parut d’autant plus bizarre au délégué administratif de Siem-Réap que l’excursion se prolongea plusieurs jours.

Dès lors, une surveillance discrète fut exercée sur MM. M. et C. qui permit de constater qu’arrivés avec de légers bagages, ils s’en retournaient avec 700 à 800 kilos de colis. La résidence supérieure, prévenue télegraphiquement, dépêcha M. Groslier à Kompong-Chnang avec mission de s’assurer que les bagages étaient bien transbordés sur le bateau de Pnom-Penh. Ce n’est qu’en arrivant dans cette dernière ville que, sur un ordre du Parquet, il fut procédé à la saisie des caisses qui étaient adressées à la maison Berthet-Charrière et Cie, de Saïgon, aux bons soins de M. C. et sous la désignation de « Produits chimiques ».

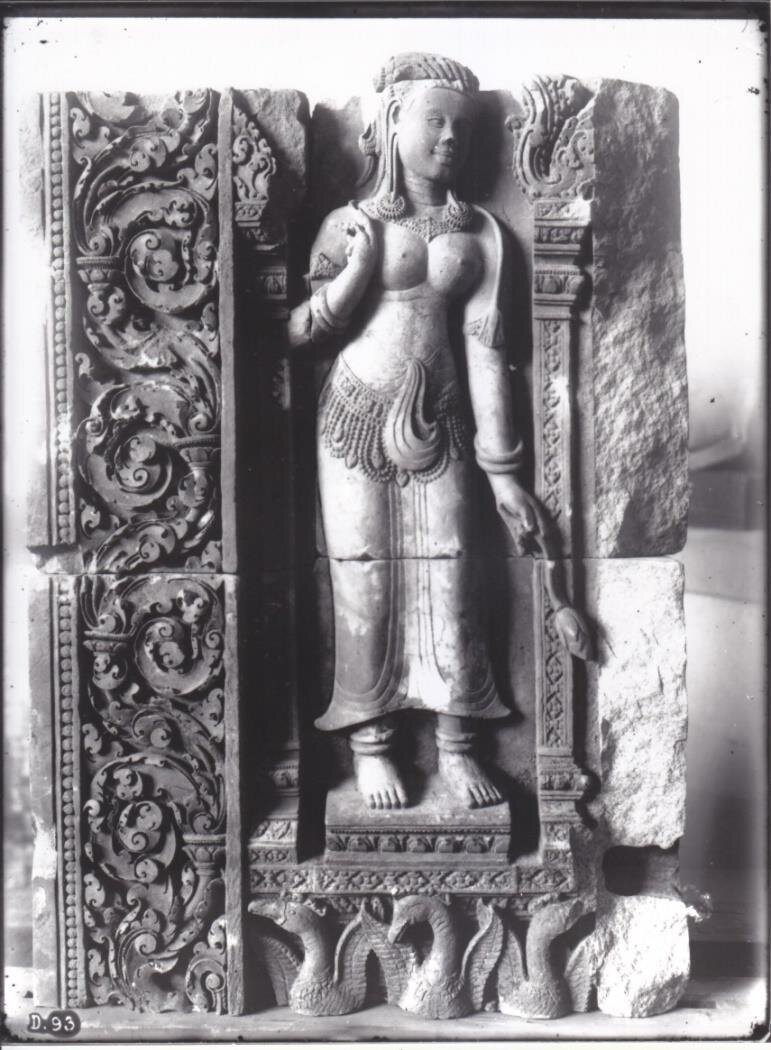

Devant l’évidence des faits, MM. M. et C. furent priés de se tenir à la disposition de la justice jusqu’à plus ample information. Nous avons pu voir, au musée Albert-Sarraut où elles sont exposées, les pièces dérobées au temps de Banteai-Say, elles constituent des merveilles admirables de l’art khmer du XIe siècle et représentent une valeur artistique considérable. Ce qui étonne le plus, c’est la science avec laquelle ces bas-reliefs ont été détachés du granit ; leur choix n’est pas moins surprenant et peut faire supposer que les inculpés n’agissaient pas dans un but désintéressé. »

Tiens ! Tiens! (Well, well!) (L’Écho annamite, 14 Oct 1924)

Jeudi, vendredi et samedi derniers, ont eu lieu, devant la cour d’appel, les débats de

l’affaire Chevasson-Malraux. On se rappelle l’odyssée de ces deux singuliers « pèlerins d’Angkor » qui, après avoir visité les ruines fameuses, dûment chargés d’une mission par le ministère des colonies, s’il vous plaît, ont essayé d’emporter, en guise de souvenirs, des bas-reliefs et des statues choisis avec un éclectisme averti. Condamnés en première instance, les deux inculpés ont fait appel du jugement. Devant la Cour, leurs avocats respectifs ont fait valoir les raisons les plus persuasives pour obtenir l’acquittement de leurs clients.Laissons de côté les considérations d’ordre juridique ; les profanes risquent de se perdre dans le maquis de la jurisprudence et des interprétations. Mais ils ont invoqué en faveur des jeunes gens d’autres arguments d’ordre sentimental, dont quelques-uns constituent des révélations particulièrement suggestives.

Me Gallois-Montbrun, le défenseur de Chevasson, a, dans son ardente plaidoirie, rappelé qu’il avait connu, au cours de sa carrière en Cochinchine, de multiples acquittements scandaleux au bénéfice de gens qui avaient volé l’argent de l’État et celui des particuliers ; il avait vu acquitter de nombreuses gens qui avaient fait pis en prenant quelque chose infiniment plus précieux que l’or : la vie humaine. — Et l’on voudrait aujourd’hui, s’est écrié l’honorable défenseur, frapper d’une manière impitoyable deux jeunes gens coupables d’avoir prélevé quelques pierres sur un

monument quasiment abandonné !

Mais alors, a fait remarquer Me Gallois-Montbrun, si on poursuit Malraux et Cbevasson pour cette peccadille, que n’a-t-on poursuivi et condamné avant eux des amiraux, des résidents supérieurs et d’autres « mandarins » d’égale importance (entendez : grands seigneurs de la Troisième République) pour des déprédations autrement graves commises au détriment des mêmes monuments ?

— On a bien, après tout, a ajouté l’éloquent maître du barreau saïgonnais, dans un passé très récent, arrangé à l’amiable d’autres affaires du même genre, alors qu’il s’agissait de rapts plus conséquents que ceux qu’on reproche à mon client. Il paraît, en effet, que récemment un officier supérieur a commis le même délit mais que l’affaire a été étouffée.

Oui, pourquoi deux poids et deux mesures ? C’est l’application de l’éternel adage : « Selon que vous êtes puissant ou misérable. » C’est égal, grâce aux avocats des deux inculpés, le public, surtout le public annamite, peut goûter la savoureuse franchise de remarques qui, dans la bouche d’un indigène, suffiraient à classer leur auteur dans la catégorie des suspects et des antifrançais. Mais les avocats ont le privilège de tout dire, et comme par surcroît, étant Français, sont de la famille, ils peuvent se permettre une petite lessive dont bénéficient leur clients grâce à l’effet rétrospectif d’un appel à la clémence.”

Regulations (L’Indochine : revue économique d’Extrême-Orient, 20 Aug 1926): “Les mesures destinées à empêcher l’exportation des objets d’art indochinois présentant une véritable valeur artistique viennent d’être renforcées par un arrêté. Désormais, il né pourra être exporté d’objets d’art antérieurs au XIXe siècle que par les ports de Haïphong, Tourane, Quinhon, Saïgon et Réam. Ces objets né pourront être exportés que si leur propriétaire demande, trois semaines au moins avant son départ, un certificat de non classement au directeur de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient en faisant une liste des objets qu’il veut emmener. Ce certificat sera donné après un examen des objets : à Haïphong, par M. Aurousseau ; à Tourane et à Quinhon, par M. Sallet ; à Saigon, par MM. Bouchot et Groslier; à Réam, par M. Groslier. Ces dispositions ont contribué à faire monter dans des proportions considérables les objets d’art annamites et, surtout, laotiens et khmers, qui sont actuellement en France et les bouddhas qui, à la colonie, se vendent 2.000 piastres sont demandés en France à près de 100.000 francs.” [Measures intended to prevent the export of Indochinese works of art presenting true artistic value have just been reinforced by a decree. From now on, artworks dating from before the 19th century can only be exported through the ports of Haiphong, Tourane, Quinhon, Saigon and Réam. These objects can only be exported if their owner requests, at least three weeks before their departure, a certificate of non-classification from the director of the French School of the Far East, making a list of the objects they want to take with them. This certificate will be given after an examination of the objects: in Haiphong, by Mr. Aurousseau; in Tourane and Quinhon, by Mr. Sallet; in Saigon, by MM. Bouchot and Groslier; in Réam, by Mr. Groslier. These provisions have contributed to the price rise in considerable proportions of Annamese and, above all, Laotian and Khmer art objects, which are currently in France and the Buddhas which, in the colony, sell for 2,000 piastres are in demand in France at nearly 100,000 francs.”

The argument that French dignitaries had no qualm in picking up artefacts while visiting Angkor has been popular in leftist circles, eager to present Malraux as a courageous agitator exposing the colonialist hypocrisy. French diplomat Albert Bodard, based in China in 1920s, the father’s of Indochina War correspondent Lucien Bodard, exclaims: “On n’a jamais vu cela, un Francais qui travaille à la révolution en Indochine avec les agitateurs jaunes! […] On monte un piege pour le haissable Malraux, c’est le révolutionnaire qu’on veut chatier, et les pierres [Banteay Srei bas-reliefs] né sont que prétexte, l’occasion, meme si Malraux exagere quelque peu de ce coté-la.” [“We have never seen this, a Frenchman working towards the revolution in Indochina along with the yellow agitators! […] So they set up a trap for the hateful Malraux, it is the revolutionary one wants to punish, and the stones [Banteay Srei bas-reliefs] are only a pretext, the opportunity, even if Malraux exaggerates somewhat in this regard.”] Problem: Malraux restyled himself as a clamorous anti-colonialist firebrand in 1925, not in 1923…

In 1928, French writer Titayna recalled that “entre Manille et Hong-Kong, un diplomate américain m’avait

fait admirer une pierre assez large d’où naissait, en bas relief, une tevada (danseuse sacrée) hallucinante. “Je l’ai emportée de votre Cambodge, m’avait-il dit … — Est-ce donc si facile ? — Je né sais pas si c’est facile pour les français … j’ai entendu raconter que des journalistes français avaient été arrêtés. Vous devez être surveillés, mais nous autres américains, on nous laisse tranquilles ! » [between Manila and Hong Kong, an American diplomat had shown for me to marvel a quite large stone from which raised in bas-relief one stunning tevada (sacred dancer). “I took her from your Cambode, he told me…- Is it that easy? — I don’t know if it is easy for the French…I heard that some French journalists [Malraux and Chevasson, the former becoming “a journalist” only after his crime] have been arrested. You are probably scrutinized but us, Americans, we are let off the hook!”].

In hindsight, we can see that EFEO field researchers in Cambodia were too absorbed with their work to become custodians of remote temples, and that Parmentier did not see through Malraux and his accomplices’ ulterior motives. He was a busy bee, as demonstrated his typical work schedule described in the Activities section of Bulletin de l’EFEO num. 24 (1924): “M. H. PARMENTIER, Chef du Service archéologique, parti à la fin de l’année précédente pour une inspection des travaux d’Ankor, a profité de cette occasion pour aller examiner avec M. H. Marchal, conservateur, l’état des ponts khmèrs qui jalonnent l’antique route qu’emprunte la voie nouvelle de Phnom Penh à Siemrap. À la fin de l’année, M. Parmentier dut aller constater les dégradations commises au temple de Bantay Srei par une bande de pilleurs de ruines, qui avaient tenté ce coup de main sous le couvert d’une mission officielle et qui venaient d’être mis avec leur butin à la disposition de la justice. Il effectua en outré quelques fouilles rapides au Bayon et à Ankor Vat pour rechercher les éléments disparus dans les remaniements postérieurs ; il put ainsi rendre au jour un curieux fronton du premier Bayon, qui avait été en partie caché par l’établissement de la terrasse supérieure, et retrouver le vieil escalier d’axe du temple central. Il se rendit ensuite de nouveau à Bantay Srei le 17 janvier 1924 pour y pratiquer une expertise demandée par le juge d’instruction de Phnom Penh sur la nature et l’étendue exacte des dommages infligés au monument. Puis il effectua le dégagement complet des parties principales, décidé par le Directeur de l’Ecole dans sa visite du 20 – 21 janvier, travail important qui dura jusqu’au 14 février. Le monument, d’une sculpture très remarquable et qui apporte d’intéressantes données nouvelles à la connaissance de l’art khmèr, a livré toute une série d’inscriptions nouvelles et semble fournir un curieux exemple d’une recherché d’archaïsme, fait connu au Champa, mais encore insoupçonné au Cambodge. Le Chef du Service archéologique fut secondé dans ses opérations par M. Goloubew, qui se chargea, avec sa maîtrise ordinaire, de l’importante documentation photographique nécessitée par la haute valeur d’art de ce minuscule ensemble. Puis M. Parmentier vint reprendre à Ankor la suite de son étude du Bayon, commencée déjà depuis de longues années pour accompagner les remarquables relevés de J. Commaille et qu’il put cette fois mener à bonne fin. Du 7 au 13 mars, il visita avec M. Goloubew les monuments et les carrières anciennes du Phnom Kulên, tournée qui amena la découverte d’un petit temple nouveau d’art classique, le Prasat Krol Romat, près d’une belle cascade, et celle d’un groupe d’animaux taillés dans les rochers verticaux qui dentèlent l’arête du plateau, oeuvres splendides de l’art prékhmèr, contemporaines de l’effort analogue tenté dans l’Inde, à Mavalipuram, par les Pallavas. Du 14 au 23, il revit en compagnie de M. Goloubew le temple de Ben Melea et le groupe de Prah Khan, complétant sur ce dernier les renseignements recueillis par M de Lajonquière, en particulier sur le curieux Prasat Stun, n° 178, le seul édifice khmèr où les gigantesques têtes qui font l’originalité du Bayon et de Banteiy Chmàr sont employées au décor d’un simple pràsàt formant sanctuaire central. D’Ankor, M. Parmentier se rendit à Kompon Chnan pour prendre connaissance d’une intéressante collection de pièces préhistoriques réunies à Samron Sen par Gayno, puis à Stun Trèn pour examiner les résultats des recherches de M. Houël, receveur des douanes dans la région de Stun Trèn et de Thala Borivat; enfin à Paksé et Savannakhet, où diverses trouvailles d’un grand intérêt lui avaient été signalées, notamment une stèle sculptée provenant de Vat Phu et un remarquable tambour de bronze du type l. De retour le 11 mai à Stun Trèn, il en repart le 15 pour Thom Khsan afin d’étudier la série des monuments d’art prékhmèr de la région, et compléter les études de MM. de Lajonquière et Groslier sur le Prah Vihear. Il gagne de là, avec quelques difficultés causées par les pluies qui ont commencé de gonfler les rivières, le groupe de Koh Ker dont il étudie les principaux édifices du 9 au 12 juin, et rentre à Stun Trèn le 23 juin, après avoir visité chemin faisant le Keak Trapàn Ku.”

A first-hand account: Jeanne Leuba

Writer, Cambodian observer for many years and Henri Parmentier’s spouse, Jeanne Leuba addressed the following letter to then French Prime Minister Raymond Barre “sur l’erreur de jeunesse, il y a presque 100 ans, d’un grand écrivain français au Cambodge” [“on a great French writer’s youthful mistake in Cambodia almost 100 years ago.] [dated 23 Jan. 1977, Ezhenthof, Austria, and published in 2016 by researcher Thong Hoeung Ong]

Monsieur le Premier Ministre,

Suivant votre réponse à ma lettre du 15 Décembre 1976, je viens vous donner les éclaircissements principaux sur ce que fut, il y a 53 ans, en Indochine, l’affaire Malraux. Comme vous le savez certainement, les merveilleux temples khmers revinrent au Cambodge en 1907, lorsque la France obtient la rétrocession par le Siam des trois provinces perdues 113 ans auparavant, Battambang, Sisophon et Siemreap. A cette époque, l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, créée par Doumer sur le modèle des Ecoles d’Athènes et de Rome, et ayant à sa tête le grand sanscritiste Louis Finot, avait déjà neuf ans. Mon mari, H. Parmentier, architecte D.P.L.G., y occupait la place de Chef du Service Archéologique. C’était donc à lui qu’avaient été confiés les sanctuaires livrés à la forêt depuis plus d’un siècle ; la Conservation d’Angkor était née, pourvue d’un architecte choisi et dirigé par lui.

Ceci pour bien poser qu’il né pouvait, en aucun cas, s’agir, à la date du scandale Malraux, « de vieilles pierres abandonnées dont personne né s’occupait », comme l’a écrit un journaleux. En 1914, le lieutenant Marec, du Service Géographique, découvrit le groupe inconnu de Banteay Srei, éloigné dans la campagne, et le signala aussitôt. Mon mari publia en 1916 de premières notes sur cet ensemble extrêmement remarquable, et ce texte tomba plus tard, par malheur, sous les yeux de Malraux, petit besogneux affolé d’argent. Il avait 23 ans et venait de se marier lorsque nous entendîmes parler, en 1923. Nous né sûmes jamais comment le couple avait extirpé à notre ami, l’ancien Gouverneur Général Sarraut, l’aller et retour gratuit sur les Messageries Maritimes et une chaude recommandation pour l’E.F.E.O. Il flottait même, autour de ce voyage, une allusion, plutôt insolite, à une donation possible (… dans les cent mille francs…peut-être…) pour les travaux encore fort dépourvus.

Le Directeur étant absent, nous accueillîmes donc, mon mari, notre sinologue Léonard Aurousseau, sa sœur et moi, ces touristes exceptionnels. Le dîner, dans l’atmosphère un peu austère d’un institut de haute science, nous laissa stupéfaits. Comme un homme en vue, intelligent et artiste, pouvait-il protéger ces deux galopins antipathiques, prétentieux et mal élevés ? D’autant plus que, visiblement, ni l’un ni l’autre né sortait d’un milieu capable de répandre sur les chantiers une manne de 100.000 francs!

Très étonnés par l’inexplicable bienveillance du Président Sarraut, mon mari et l’orientaliste Victor Goloubew se déplacèrent néanmoins pour escorter le ménage à Angkor et lui faire les honneurs des principaux sanctuaires. Puis, le laissant installé au bungalow (seul hôtel existant alors), nous rentrames au Tonkin. Environ une quinzaine de jours après son retour, mon mari reçut un télégramme de M. Debyser, gérant de bungalow, annonçant que des gens avaient décampé dans la nuit, en charrette à bœufs, sans payer un centime de leur dû. Préparés par l’impression que nous en gardions le délit de grivèlerie passa au second plan devant ce que nous comprîmes aussitôt. Mon mari repartit immédiatement, alerta la police et arriva avec elle juste au moment où les voleurs allaient se mettre à l’abri en franchissant la frontière siamoise.

Ramenés à Saigon et incarcérés, leurs bagages saisis livrèrent, avec tout l’outillage apporté de Paris pour les découper, les sculptures exquises dont ils avaient odieusement mutilé le temple adorable de Banteay Srei. Le scandale fut énorme, tant chez les asiatiques que chez les européens. La vente de ces bijoux était, paraît-il, négociée d’avance… Malraux fit plusieurs mois de cellules en attendant son procès. Sa femme singea la folie, prétendant voir des petits chats partout; tant, que l’on finit par s’en débarrasser en l’expulsant.

Condamné à une assez forte peine de prison pour grivèlerie et dégradation dans un monument historique. Malraux fit appel, cependant qu’à Paris sa mère, ou sa femme, ou les deux ameutèrent un clan d’écrivains qui eussent mieux faire de s’occuper de leurs oignons, mais obtinrent certainement des appuis influents car le voleur fut relâché, à l’indignation générale. La publication immédiate de La Voie royale provoqua chez les uns un éclat de rire, chez les autres de profonds dégoûts. Ce mauvais roman feuilleton où de lourdes affabulations caricaturales essaient de ridiculiser des savants qui le dépassaient de cent coudées, fit apparaître à l’auteur sous le jour d’un moutard qui vient de recevoir une fessée et qui, enfermé dans sa chambre, trépigne de rage en insultant ses parents.

Il tenta quelques mensonges au cours d’interviews, pour se faire valoir (comme, par exemple, une connaissance du sanscrit dont il eut été bien incapable de prononcer un seul mot !). Puis, avec La Condition humaine, il trouvera sa forme littéraire et l’argent. Il accédait à la vie aisée et, suivant le proverbe allemand, « était prêt, comme la ciboule, à flotter sur toutes les soupes ». Ce qu’il né manqua pas de faire. Il est arrivé aujourd’hui au bout de sa carrière, dont j’ai suivi l’évolution avec une certaine ironie.

Voilà ce que fut exactement l’un des plus honteux éclats dont un européen ait sali la France aux yeux des indigènes. Et à la colère des Blancs. Lorsqu’il est revenu au Cambodge, environ quarante ans plus tard, traîné par de Gaulle, il s’est prudemment terré au maximum dans l’ombré du Général. Son nom grondait sur toutes les bouches.

Veuillez agréer, Monsieur le Premier Ministre, l’expression de ma très haute considération.

Jeanne Leuba

[Mr Prime Minister,

Following your response to my December 15, 1976, letter, I share with you here some utmost clarifications on “the Malraux Affair” that occured 53 years ago in Indochina. As you’re certainly aware of, the wonderful Khmer temples were given back to Cambodia in 1907, when France obtained the retrocession by Siam of the three provinces lost 113 years previously, Battambang, Sisophon and Siemreap. At that time, the French School of the Far East (EFEO), founded by Doumer on the model of the Schools of Athens and Rome, and headed by the great Sanskritist Louis Finot, was already nine years old. My husband, H. Parmentier, D.P.L.G. architect, held the position of Head of the Archaeological Service there. It was therefore to him that the sanctuaries given over to the forest for more than a century had been entrusted. The Conservation of Angkor was born, provided with an architect chosen and directed by him.

This is to make it clear that it could not, in any case, be a question, at the date of the Malraux scandal, of “old abandoned stones that no one took care of”, as some reporter wrote. In 1914, Lieutenant Marec, of the Geographical Survey Service [SGI], discovered the unknown group of Banteay Srei, far away in the countryside, and immediately reported it. In 1916 my husband published the first notes on this extremely remarkable ensemble, and unfortunately this text came later under the eyes of Malraux, a little needy man desperate for money. He was 23 years old and had just gotten married when he heard about it, in 1923. We never knew how the couple had extracted from our friend, the former Governor-General Sarraut, the free round trip on the Messageries Maritimes and a pressing recommendation to the E.F.E.O. There was even floating, around this trip, a rather unusual hinting at a possible donation (… in the hundred thousand francs… perhaps…) for a work which was still in demand of funding.

The Director being away, we therefore welcomed, my husband, our friend the sinologist Léonard Aurousseau, his sister and I, these uncommon tourists. The dinner, in the somewhat austere atmosphere of a higher science institue, left us stunned. How could a prominent, clever and artistic man, begin to protect these two unpleasant, pretentious and ill-mannered scoundrels? Especially since, clearly, none of the pair came from an environment capable of spreading a windfall of 100,000 francs on the archaelogical sites!

Stunned by this inexplicable benevolence of President Sarraut, my husband, and the orientalist Victor Goloubew, nevertheless traveled to escort the pair to Angkor and do them the honors of the main sanctuaries. Then, leaving him installed in the bungalow (the only hotel in existence at the time), we went back to Tonkin. About a fortnight after his return, my husband received a telegram from Mr. Debyser, the Bungalow manager, announcing that these people had decamped at night, in ox carts, without paying a cent of their dues. Alerted by the impression they had made on us, we immediately understood what was at stake beyond the petty crime of ” dine and dash”. My husband left at once, alerted the police and arrived with law inforcement officers just as the thieves were about to take cover by crossing the Siamese border.

Brought back to Saigon and incarcerated, their seized luggage exposed, along with all the tools brought from Paris to cut them, the exquisite sculptures which they had odiously mutilated at the adorable temple of Banteay Srei. The scandal was enormous, both among Asians and Europeans. The sale of these jewels was, it seems, negotiated in advance…Malraux spent several months in house arrest while awaiting his trial. His wife faked madness, pretending to see little cats everywhere; so much so that one ended up getting rid of them by expelling them.

Sentenced to a fairly long prison sentence for causing damage to a historic monument, Malraux appealed, while in Paris his mother, or his wife, or both, brought together a coterie of writers who would have done better minding their own business, yet certainly obtained influential support because the thief was released, to general outcry. The immediate publication of La Voie royale provoked a big laugh among some, and deep disgust among others. This bad dime novel, in which heavily caricatural fabrications attempt to ridicule scholars who surpassed him by miles, exposed its author as a brat who has just received a spanking and who, locked in his room, stamps his feet and rages insults at his parents.

He attempted a few lies during interviews, just to show off — like, for example, a knowledge of Sanskrit of which he would have been incapable of pronouncing a single word!. Then, with Man’s Fate, he found his literary form and money. He achieved a comfortable life and, to quote the German saying, “was ready, like spring onions, to float on all the soups”. Which he did not fail to do. Today he has reached the end of his career, the path of which I have followed with a certain ironical eye.

This is exactly how happened one of the most shameful outbursts with which a European man has tarnished France in the eyes of the natives. And to the anger of white people. When he returned to Cambodia, around forty years later, trailed by de Gaulle, he prudently hid himself as much as possible in the General’s shadow. His name was roaring on everyone’s lips.

Please accept, Mr Prime Minister, the expression of my highest consideration. Jeanne Leuba]

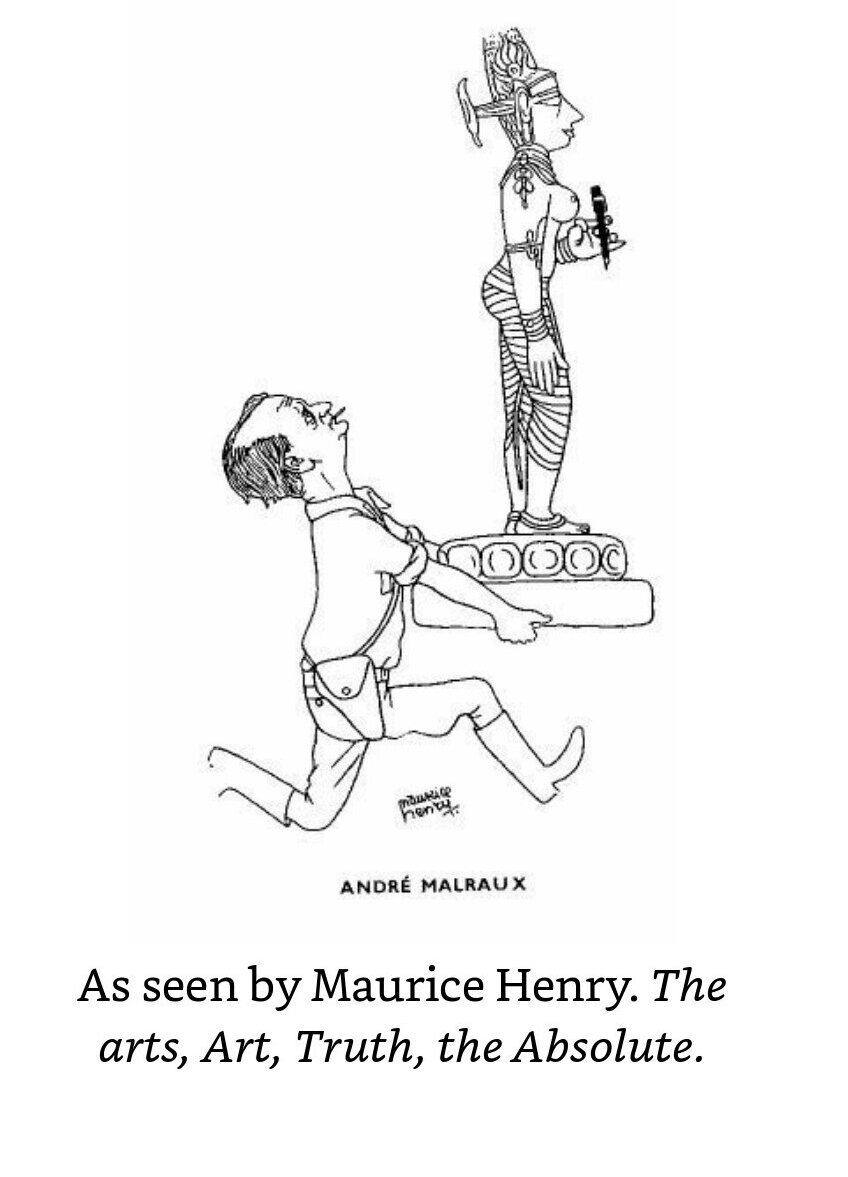

Reverberations

Malraux’s 1923 raid on Banteay Srei was a crime, even if the French colonial justice finally deemed it as misdemeanor, even if French intellectuals including luminaries such as André Breton or Max Jacob petitioned in his favor in 1924, even if he came down in Western history as the man who “has led an archeological expedition to Cambodia, been connected with Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Tse-tung – and has been active in the civil war – participated in the defense of his country – been involved with General de Gaulle”, to quote President J.F. Kennedy in his toast to the French Minister during a White House Gala Dinner on 11 May 1962, even if much more serious crimes of looting are currently being solved by the campaign for repatriation of stolen artworks.

- Malraux himself rarely commented on his arrest and trial after the Banteay Srei debacle, one exception being the interview with André Rousseaux for the French magazine Candide a few days after The Royal Way release, on 13 Nov 1930 [“Un quart d’heure avec André Malraux”, available on www.malraux.org and here]. Ch7aracteristically, he vehemently decried that publication, and Candide published his protest one week later, on 20 Dec 1930. According to Rousseaux, a Catholic rightwing publicist who was nevertheless to censure collaborationism one decade later, when pressed to comment on Banteay Srei, Malraux told him: “Remarquez d’abord, dit-il, que j’étais en mission gratuite, mission qui me donnait seulement le droit de réquisition auprès des indigènes. Je n’avais, par conséquent, rien d’un fonctionnaire appointé et tenu à certaines obligations. J’opérais à mes frais. Et les sculptures que j’ai rapportées, d’autres auraient pu aller les prendre avant moi, s’ils avaient eu envie de s’enfoncer dans la brousse. D’ailleurs, si on né les avait pas saisies, j’en aurais donné la moitié au musée Guimet. Maintenant, il s’agit de les reprendre. Elles sont séquestrées au musée de Phnom-Penh, qui est propriété du roi du Cambodge. C’est un nouveau procès, car la Cour de Cassation a bien annulé les jugements déjà rendus, mais il reste à obtenir le jugement définitif…” [Notice first, he said, that I was on a gratuitous mission, a mission which only gave me the right of requisitioning natives. I was not in any case, therefore, some sort of civil servant appointed and bound by certain obligations. I operated at my own expenses. And the sculptures that I brought back, others could have gone and taken them before me, if they had wanted to go deeper into the bush. Besides, had they not be seized, I would have given half of them to the Guimet Museum. Now, it is time to take them back. They are sequestered in the Phnom Penh museum, which is owned by the king of Cambodia. This is a new trial, because the Court of Cassation has indeed voided the sentences already pronounced, but it remains to obtain the final judgment…’] Khmer statues being “sequestered” by the sovereign of a country still under colonial rule: the logics of the purported anti-colonialist is hard to follow.

- The most elaborate and blatant attempt to absolve Malraux from his crime certainly remains Walter Langlois’ 1966 André Malraux: The Indochina Adventure, who pigheadedly paints the “adventure” of a young idealist engaged in some “intense personal struggle within oneself, this “combat” with mortality”. Every piece of Malrucian fantasy is taken for granted by the American scholar, professor of French literature at Kentucky University, even the alleged “ongoing project of writing a major comparative study on Siamese and Khmer arts”. Langlois notes that the young Malraux had been commissioned by “an American connoisseur to negotiate the purchase of the important collection of Asian art” belonging to Prince Damrong, a Siamese dignitary that would be the guest of EFEO at Angkor in January 1924. “Looking back over Malraux’s achievements, one can see that his experience in Indochina was crucial. In a sense, the author of Man’s Fate and Man’s Hope was created by the Phnom Penh trial and the subsequent injustices he witnessed in Cochinchina,” writes Langlois (p 229) to our bafflement.

- Did Malraux wish to be caught? In Axel Madsen’s Malraux: A Biography (Open Road Distribution, 1976, ISBN: 978−1−5040−0856−3), certainly the most nuanced and insightful portrait of the “little thief”, we read: “In a few months we’ll be rich. Or lost. Clara is decidedly scared. That she would be party to the adventure was never even discussed. A good sign? Friends and acquaintances are hardly surprised: they envy but are also suspicious of the audacity. Max Jacob sniggers in a letter to Kahnweiler: “A Malraux mission … Oh well, he’ll find himself in the Orient. He’ll become an orientalist and end up at the College de France, like Claudel. He’s the type to have a chair.” The poet knew from the first time they met that Andre would never stay with writing-the only truly holy mission in his eyes. Max believes that Malraux loves his century. Wrong: the way sought by Andre in the Orient certainly does not lead to the Academie. And for the time being, his baggage contains a dozen handsaws. And the seven sandstone sculptures that will be seized from his trunk when he arrives at the mouth of the Mekong the following Christmas will get him not some academic chair but a three-year prison sentence. Everything of value escapes and, recaptured by routine, must rot in jail. Real books are written in a cell: Dostoyevsky, Cervantes, Defoe, says The Walnut Trees of Altenburg.”

- La Voie Royale, a quest for Tantric Buddhism dharma? This is the daring proposition put forward by Korean scholar Kim Woong-Kong, who has written several essays on French literature: “Il est naturel que diverses lectures de La Voie royale aient été faites. Quand ce roman est lu d’une façon fragmentaire, ou que son réseau de mâyâs n’est pas dévoilé, il montre plusieurs figures, par exemple une vision nihiliste nietzschéenne, une révolte prométhéenne, un drame absurde existentialiste, une aventure conradienne, un érotisme d’antidestin de l’affirmation de soi, une critique de la civilisation occidentale etc. Ces lectures né sont pas forcément mauvaises. De telles couleurs contribuent à enrichir le roman et les profondeurs de l’œuvre. Elles sont comme les pelures d’oignon à éplucher dans le processus de la découverte d’un trésor dissimulé dans le texte encodé. La nouvelle construction que j’ai proposée devrait les englober toutes parce qu’elle vient de l’analyse de leur présupposition. Le texte est un espace qui s’ouvre à la mesure du goût, de la culture et de la connaissance du lecteur. Bien que La Voie royale soit un roman interrogatif sur la quête de La Voie du bouddhisme, elle couvre une réflexion profonde sur l’histoire et la civilisation d’Occident. Cela aboutit à un vaste champ d’interrogation intellectuelle qui devrait faire dialoguer l’Asie et l’Occident l’une avec l’autre […] Pourquoi ces indigènes qui vivent dans ce monde symbolique doivent-ils être peints commes des sous-hommes ou des brutes sous le regard de Claude ? Comparons l’attitude de ce jeune protagoniste à celle du vieux. En fait, on né trouve pas de cas où Perken regarde les Moïs à la manière de Claude. En revanche, il utilise simplement les insectes de la forêt comme des métaphores pour enseigner à Claude le tragique humain, ou le ruminer. Une telle différence tiendrait d’abord au fait que Perken s’est assimilé au monde des indigènes après les avoir conquis. Bien qu’ils vivent une vie primitive, séparés de la civilisation matérialiste, ils gardent leur foi dans le bouddhisme tantrique et pratiquent leur « cultes érotiques ». On peut supposer que les chefs des tribus, ou ceux des villages comme Savan sont parvenu à un niveau assez élevé dans leur connaissance et leurs pratiques de cette religion. Néanmoins, de ce côté aucun personnage concret sauf Savan, ni aucune information n’apparaissent. Le lecteur né peut savoir directement comment Perken s’est initié à leur bouddhisme tantrique. Certes, ces faits romanesques s’inscrivent dans le cadre de la poétique symboliste du roman : si le processus d’initiation de Perken à la religion est directement dit ou évoqué, cette poétique même se détruirait. De toute façon, non seulement Perken, comme un ethnologue ou un anthropologue, a compris leur monde, mais aussi il s’y est même initié. C’est grâce à cette situation personnelle qu’il né regarde pas les Moïs négativement. Pourtant, Claude est dans une autre situation. La connaissance qu’il a obtenue de la pensée indienne avant de rencontrer Perken est livresque. Comme il a ainsi abordé cette pensée à travers sa lecture, il l’aurait tenue pour la haute spiritualité d’une autre civilisation.” [“It is natural that various interpretations of The Royal Road have been developed. When this novel is read in a fragmentary way, or when its network of mayas is not revealed, it shows several faces, for example a Nietzschean nihilistic vision, a Promethean revolt, an absurd existentialist drama, a Conradian adventure, an anti-destiny eroticism of self-affirmation, a critique of Western civilization, etc. These readings are not necessarily bad. Such colors contribute to enriching the novel and its depths. They are like the onion skins to be peeled in the process of discovering a treasure hidden in the encoded text. The new construction that I have proposed should encompass them all because it comes of the analysis of their presupposition. The text is a space which opens to the extent of the taste, culture and knowledge of the reader. Although The Royal Road is an interrogative novel on the quest for The Way of Buddhism , it covers a profound reflection on Western history and civilization. This leads to a vast field of intellectual questioning which should bring Asia and the West into dialogue with each other […] Why must these natives who live in this symbolic world be painted as subhumans or brutes under Claude’s gaze? Let’s compare the attitude of this young protagonist to that of the old man. In fact, we do not find any case where Perken looks at the Mois in the same way as Claude. On the other hand, he simply uses the insects of the forest as metaphors to teach Claude about human tragedy, or to ruminate on it. Such a difference would firstly be due to the fact that Perken assimilated into the world of the natives after having conquered them. Although they live a primitive life, separated from materialistic civilization, they keep their faith in Tantric Buddhism and practice their “erotic cults”. We can assume that the chiefs of the tribes, or those of villages like Savan, have reached a fairly high level in their knowledge and practices of this religion. However, on this side no concrete character except Savan, nor any information appears. The reader cannot know directly how Perken became initiated into their Tantric Buddhism. Certainly, these fictional facts are part of the symbolist poetics of the novel: if the process of Perken’s initiation into religion is directly said or evoked, this very poetics would be destroyed. In any case, not only did Perken, like an ethnologist or anthropologist, understand their world, but he was even initiated into it. It is thanks to this personal situation that he does not look at the Moïs negatively. However, Claude is in another situation. The knowledge he obtained of Indian thought before meeting Perken is bookish. As he thus approached this thought through his reading, he would have considered it to be the high spirituality of another civilization.] By tearing away the goddesses of Banteay Srei, mistaken for apsaras, celestial dancers, Malraux and his characters supposedly attempted to reach Tantric extasis: “Les éléments tantriques de l’érotisme mystique auquel initient les Apsaras, exposés par Perken, né sont pas expliqués en termes mystiques ou ésotériques mais développés dans la dimension intellectuelle, imaginaire et sensible de l’auteur. Autrement dit, ils sont plutôt rationalisés et occidentalisés. Perken prend l’amour pour une illusion de la jeunesse, et aborde, du point de vue de la dualité des sexes, le statut de la femme par rapport à l’homme. […] “Un homme qui pense, non à une femme comme au complément d’un sexe, mais au sexe comme au complément d’une femme, est mûr pour l’amour” dit Perken. Ici, « un sexe » indique l’homme, et Perken parle à la place de l’homme. Selon sa thèse, l’homme doit considérer la femme comme son complément. Mais que veut dire ce « complément » ? La femme serait en effet un être qui aide l’homme à rejoindre l’invisible originel, par l’union indifférenciée des deux sexes, c’est-à-dire par la destruction de la dualité sexuelle.[…] Il en va de même pour la femme. Sous l’angle du tantra, si l’homme prend la femme pour son complément, et réciproquement, s’ouvre la voie de l’érotisme vrai qui dépasse le sentiment illusoire d’amour. L’érotisme n’est ici que le changement nominal de la vision tantrique de l’amour sexuel. C’est ce que Perken enseigne à Claude.” [“The tantric elements of mystical eroticism to which the Apsaras initiate, as exposed by Perken, are not explained in mystical or esoteric terms but developed in the intellectual, imaginary and sensitive dimension of the author. In other words, they are rather rationalized and Westernized. Perken takes love for an illusion of youth, and addresses, from the point of view of the duality of the sexes, the status of woman in relation to man. […] “A man who thinks, not to a woman as the complement of a sex, but to the sex as the complement of a woman, is ripe for love” says Perken. Here, “a sex” indicates man, and Perken speaks instead of man. According to his thesis, man must consider woman as his complement. But what does this “complement” mean? Woman would in fact be a being who helps man to reach the original invisible, through undifferentiated union of the two sexes, that is to say by the destruction of sexual duality.[…] The same goes for women. From the angle of tantra, if the man takes the woman as his complement, and vice versa, the path to true eroticism opens up which goes beyond the illusory feeling of love. Eroticism here is only the nominal change of the tantric vision of sexual love. This is what Perken teaches Claude.”](KIM, Woong-Kwon, La Voie royale d’André Malraux: secrets d’un chef-œuvre, Kindle French Edition, 2019).

- In his recension of Raoul Marc Jennar’s Comment Malraux est devenu Malraux (How Malraux Became Malraux, Cape Bear, Perpignan, 2015), Peter Tame, professor at Queen’s University, Belfast, also follows the path of supposed erotic fascination to explain (and justify?) the Banteay Srei looting : “Non des moindres est le lien entre l’intérêt de Malraux pour la littérature erotique et l’attrait esthétique des formes voluptueuses des Apsaras cambodgiennes du temple de Banteay Srei, qui est bien souligné par l’auteur [Jennar].” [“Not least is the connection between Malraux’s interest in erotic literature and the aesthetic appeal of the voluptuous forms of the Cambodian Apsaras at Banteay Srei temple, which is well emphasized by the author [Jennar]”] Really? The same Malraux who was to lament that Titian’s Venus was now “Venus in the Folies-Bergere, [where] la peinture officielle annexe peu à peu l’imaginaire et l’irréel à l’apparence enfin victorieuse” [if that makes any sense]. (in La Vénus des Folies-Bergère et celle du Titien, Le Figaro littéraire, n° 1407, 5 mai 1973, p. I‑II).

- “André Malraux: The looter of Banteay Srei who rose to high political office”, is the title of a presentation made by Dr. Lia Genovese to the Siam Society, Bangkok, on 25 May 2017. Dr. Genovese will soon publish the full extent of her years-long inquiry on the Banteay Srei theft.

- In his Signed, Malraux (tr. by Robert Harvey, University of Minnesota Press, 1999), Jean-Francois Lyotard summarizes the “lunatic” scheme behind the 1923 expedition: “Pressed by his 1923 stock market failure, he has a ready plan of attack. An unexplored corner of Asia awaits him-in the Cambodian marshes north of the Tonle Sap, at the edge of the forests rising up toward Siam. The plan: to locate documented remains of admirable preclassical Khmer temples left to decay in the rotting pits full of slimy animals. Rescue the gods and dancers from the vermin, bring them back to Kahnweiler [Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler, a German-born art dealer who moved to Paris in 1920], who would sell them in America. Does this way of making a living seem a little twisted to you? It is in the straight line of his obsession. This, Clara reads perfectly and has no objection. Ready to take up this challenge as she has the others, she just wonders how far the lunatic will go.

This is what Andre had found in books he read: a culture has just been identified in northern Cambodia that is chronologically situated somewhere between the brick temple of the Funan kingdom of the earliest centuries and the grand ninth-century ensembles of Angkor. A French officer sent in 1914 by the geographic service to map the region had discovered, by chance, the ruins of a sanctuary northwest of Angkor Wat, in a place called Benteai-Srey or Bentay-Srei. The Ecole Franc, created in 1898, then sent an archaeologist, Desmazure [Georges-Marie-Léon Demasur, see below] to study the site; he disappeared. The Great War breaks out in Europe. In 1916, the director of the EFEO’s archaeological service, Henri Parmentier, completes the preliminary measurements and publishes the first monograph on the temples in the Bulletin de l’EFEO (1919), complete with supporting photographic evidence, under the title: “The Art of Indravarman,” from the name of the sovereigns of these intermediary kingdoms-later called Chen-La-dating from 700 to 1000. Parmentier deplores the neglect to which this splendid monument has been left. Escheat auspicious for exploits and for exploitation: a more perfect objective could not have been wished for. A note he tracked down in the Revue archeologique ( 1922) confirms it: Harvard’s Fogg Museum has just “procured” a splendid bodhisattva head from Angkor Wat. One can very well go ahead and pillage, then. What’s more, Benteay-Srey is not a protected site. It isn’t even certain whether it belongs to the king of Cambodia or falls under the jurisdiction of the French protectorate. Andre scours the official bulletins. A 1908 order of the governor-general of Indochina, dated 1908, had classified all edifices “discovered or to be discovered” in the western provinces of Cambodia as protected monuments. And he is reminded of this order once he arrives. But in a recent speech before the Chamber of Deputies, Daladier, then minister of colonies, said he judged this procedure of preservation by decree to be “flagrantly illegal.” And now, in August 1923, a measure of the general government has just created a commission for the preservation of sites. He’ll have to act quickly, before the EFEO’s exclusive rights over Khmer treasures become law. Upon his arrival in Hanoi in mid-November, Andre will learn that the king of Cambodia had just signed an act protecting the sites scattered throughout the jungle. The idea of defying princes and governors enchants Andre. Things are getting desperate. The Malraux are penniless.” - Christopher Hitchens (New York Times, 10 April 2005): “Raymond Aron’s later judgment of Malraux (“one third genius, one third false, one third incomprehensible”) would be remarkably useful in evaluating the novels with which Malraux made his reputation. These adaptations of his Asian travels, “Les Conquérants” (1928), “La Voie Royale” (1930) and “La Condition Humaine,” amounted to a trilogy on the Chinese revolution. In tone, they swung awkwardly between a sort of vulgar Marxism and a Bonapartist invocation of la gloire. Indeed, Malraux never lost his admiration for Napoleon, and produced a potboiling biography of him at the same time.”

- In his “Hubris to humiliation: Western imperialism in Southeast Asia as reflected in metropolitan literature” (Sheffield Hallam University, 5 March 2013”, Adam Smith analyzes the The Royal Way through three analytical frameworks drawn by Panivong Norindr (in Phantasmatic Indochina: French Colonial Ideology In Architecture, Film, And Literature, Duke University Press, 1996): “the “phantasmatic elaboration of a feminised Indochina”, “the mise en scène of the masculinist desire”, and the “aesthetic and ideological ramifications of this type of ‘archeological’ representation”. The first issue is the absence of women in the novel (other than as erotic or submissive objects) which is all the more surprising given that Malraux was in fact accompanied by his wife during his own trip to the jungle. Malraux’s defence was that he was unable to imagine a female character but perhaps a more sanguine explanation is that the presence of a woman

would have interfered with the two protagonists’ liberty to fantasise about girls. The colonised land has often been represented as feminine and it therefore suited Malraux to emphasise the masculinity of the two tomb-raiders. Moreover, we note that the characters spend more time dreaming about women than actually doing anything about it, and in Perken’s case, age has made him unable properly to possess the female body. This is a surprisingly prescient parallel to French colonialism generally: much fantasy and claim of glory, an obsession about representations of empire that outweighs the actual possession, and an ultimately impotent colonial policy. It is hard to imagine that Malraux consciously drew this parallel in 1930.” - Was Malraux’s action in Banteay Srei ‘hateful’? One hundred years later, the question remains unfortunately controversed. Lucas Demurger has devoted one entire chapter to “La haine André Malraux: Rhétorique de l’antimalrucianisme après 1947” [“Hating André Malraux: Rhetorics of Antimalrucianism after 1947”, in Signés Malraux. André Malraux et la question biographique, Classiques Garnier, Paris, 2016], yet he does not assess the fundamentally ethical question raised by the assault on Banteay Srei’s devatas [described as “statuettes” in many contributions to the bulletin Présence d’André Malraux, as if they were small stone trinkets picked up from the ground]. A particularly gullible defence of Malraux’s desecration at Banteay Srei can be found in Sebastien Cauquil’s “Malraux en Indochine: l’au-delà des frontieres” (in Présence d’André Malraux n 10, Actes du Colloque au CEVIPOF, Paris, 2013, pp. 141 – 155): “Il [Malraux] voit l’opportunité de se renflouer rapidement en ramenant des vestiges du temple de Banteai-Srey pour les vendre. D’autre part, il est motivé par l’envie de faire franchir à des oeuvres d’art les limites géographiques pour éclairer les rapports entre l’art khmer siamois ainsi que l’identité proprement occidentale. N’oublions pas qu’il devait faire profiter le musée Guimet de ses recherches et d’une partie de ses trouvailles. […] Et pour rapprocher deux civilisations et sans doute mieux appréhender sa propre identité et culture, il faut franchir les seuils qui nous séparent des autres et restreignent notre champ intellectuel.” [“Malraux sees the opportunity to bail himself out [of his losses on the stock market] quickly by bringing back remains of the temple of Banteai-Srey and selling them. On the other hand, he is motivated by the desire to make artworks cross the geographical boundaries to shed light on the relationships between Siamese and Khmer arts, as well as specifically Western identity. Let us not forget that he was to share his research and some of his findings with the Guimet Museum. […] And to bring two civilizations together and undoubtedly better understand our own identity and culture, we must cross the thresholds that separate us from others and restrict our intellectual field.”] With picks and saws?

- In need of reassessment. Geoffrey T. Harris (Malraux: A Reassessment, MacMillan Press, London, 1996, 269 p: ISBN 978−1−349−39629−0), another professor of French: “Interviewed about La Voie royale in 1930, Malraux declared: ‘I set out to tell the truth about adventure. First of all, a truth which is simply synonymous with accuracy. Similarly, it took the last war for literature to reveal that war is something dirty, in the most

literal sense of the word’. Certainly Malraux’s novel does not glorify adventure or the adventurer. The setting is repulsive and alien — ‘The forest and the heat were however more oppressive than the anxiety…’ […] In his comments on his second novel, Malraux stresses that La Voie royale, unlike the traditional adventure novel, is meant to depict adventure not as a means to an end but as an end in itself. But the adventure Malraux refers to is of a very specific kind: ‘[Adventure] is the obsession with death’ ([L’aventure] est /‘obsession de Ia mort). Malraux’s adventurer is like a gold-prospector who, in a moment of lucidity, admits that rather than looking for gold, ‘he is running away from himself’ (il se fuit lui-meme). In other words ‘he is at the same time running away from and running towards his obsessive fear of death’ (il fuit sa hantise de Ia mort en meme temps qu’il court vers elle). Rarely articulated in Les Conquerants, despite its numerous victims, death, the ultimate incarnation of man’s futility, is the primary dynamic of the discourse in La Voie royale.” - On 25 January 2024, independent researcher Lia Genovese gave a lecture at The Siam Society, Bangkok, titled: “Romance, Crime and Political Awakening: Uncovering Hidden Narratives, a Century After André Malraux Plundered Banteay Srei”.

Banteay Srei, A (X)Xth Century Temple?

In the 2021 EFEO book-tribute to Henri Marchal, archaeologist Eric Bourdonneau brilliantly shows how Banteay Srei, the first Khmer temple to be almost entirely reconstructed, has gained pictural and symbolical preeminence in modern representations, the temple dating back from the X (10th) century becoming a XX (20th) one. For instance, Van Molyvann’s iconic Independence Monument in Phnom Penh was designed after the Banteay Srei tower tops. Some authors have credited André Malraux for “discovering” the precious monument, which is ludricous, or at least for bringing French archaeologists to hasten its renovation after his 1923 raid, which is possible, granting that its modest size made complete restoration an easier task than, let us say, the sprawling Beng Maelea complex nearby.

George R. Nelson (1927−1992), set decorator for Apocalypse Now, along with Art Director Angelo Graham and Production Designer Dean Tavoularis, drew inspiration from Banteay Srei more than any other Khmer temple for the nightmarish Cambodian temple-compound inhabited by Colonel Kurtz’s irregulars. Set decorators’ work was so minitious that Special Effects Director John Frazier recalled in an interview: “We would party up at the Pagsanjan Hotel, and there was a group of French people who had gone up to the world-famous rapids. They thought the temple set [which was part of the Kurtz compound] was real. I said, ‘We’re going to blow that up in a couple of days.’ They replied, ‘What are you talking about?’ I said, ‘It’s a movie set.’ They said, ‘You can’t blow that up. It’s like thousands of years old!’ The production shut down for a week while people came in to make sure it was a movie set.”

Olivier Todd (Malraux: A Life, tr. by Joseph West, Knopf Doubleday, New York, 2005) is right in reminding us that La Tentation de l’Occident, his first major book (Gallimard, Paris, 1926) was dedicated “To you, Clara, as a souvenir of the temple at Banteay Srey.” Todd, who disliked Malraux for his flirtation with Communism and Stalinism, recalls former French President Jacques Chirac — himself a lover of Asian and African art — commenting about Malraux’s books on art: “They lack scientific rigor. But nobody spoke better than he about fetishes.”

Lyotard: “After a few days of crawling about in the depths, the Malraux team stumbles upon Banteai-Srey. “Virgin’s fortress” is Clara’s translation; like “Magdeburg;’ in German: “a pink, decorated, ornate temple; a tropical forest Trianon.” The halt in wonderment, “as silent as children who have just been given a present that utterly fulfills their hopes”. Then, just as quickly, they get on to the work with the saws. These break, however. So they grab the stonecutters to get some leverage. Three days later, seven sculpted blocks have been removed in good condition. Now that’s writing! They’re sent off to Phnom Penh, where a firm will export them to France. Following a dispatch from Cremazy, the ragamuffins are arrested in the middle of Christmas night aboard the launch carrying them down the Mekong, charged with the theft of cultural treasures, and placed under house arrest pending a full investigation in Phnom Penh.”

In January 1914, when Lieutnant Marec hands over to EFEO several artifacts he had brought from there, including the now famous Shiva with Uma splendid sculpture, the temple is known to French researchers as “the temple of Ishvapura”. Marec was not an archaeologist, though, but a cartographer in search of the ancient roads connecting Angkor to Phnom Kulen, Preah Vihear and Wat Phu further on to the northeast.

Victor Goloubew, after flying over a large area including Phnom Kulen, Banteay Srei, Bakong and the West Baray on March 4, 1936 — five weeks before taking Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard to a flight over Angkor — , often refers to “Lieutnant Marec, topographist with the Société Géographique”, for instance: “En volant ensuite vers l’Ouest, nous apercevons le Trapan Tuk et le Trapan Khnàr, indiqués tous les deux sur la carte du lieutenant Marec. Plus à l’Ouest encore, apparaissent plusieurs autres bassins, carrés ou rectangulaires. Ce que nous n’arrivons pas à reconnaître, c’est l’ancienne chaussée signalée dans cet endroit par le lieutenant Marec ; si l’on s’en réfère aux indications fournies par cet officier topographe, elle se dirige vers le N.-O., en passant entre le Tg. Tuk et le Tg. Khnàr. Il n’est pas impossible que l’angle N.-E. de ce dernier trapang marque le point où la chaussée en question rencontre une route se dirigeant droit à l’Est, vers Bantay Srei.” (‘Reconnaissances aériennes au Cambodge’, BEFEO 36, 1936, pp. 465 – 477).

George Groslier had missed Banteay Srey during his 1913 – 1914 mission in the area, coming from Preah Vihear to Angkor through Koh Ker and Beng Melea, then continuing on to Banteay Chhmar, where his motorcade was allegedly the first automobile to reach this remote temple.

Following Marec’s path, EFEO architect and draughstman Georges-Marie-Léon Demasur (1885, Alsace, France — 1st May 1915, Seddul-Bahr, Dardanelles, Turkey) was studying the mines of Koh Ker when Marec’s cartographic prospection brought him to Phnom Dei sanctuary, first, and to Banteay Srei. Having volunteered to join World War I fight in Europe, he left Saigon in November 1913, became military instructor for Senegalese troops in Nice (France), and finally fought in the deadly Dardanelles offensive. Contrary to the fate of two French explorers who had been killed in the Stung Treng area, fate that Malraux had become obsessed with, Demasur’s tragic end was the proof that explorers could be killed not by “savages” but by the same authorities they were working for.

Ironically, Henri Parmentier, who had been so lenient with Malraux in 1923, came to think that the reconstruction of the temple was directly linked to the 1923 raid. In the Guide Parmentier (1960 edition), one reads: “Banteay Srei, temple restauré apres un pillage de sculptures qui a fait un certain bruit en 1923. C’est sur ce temple que s’est effectuée la première reconstruction tentée par l’Ecole, ou ont repris place les pierres arrachees par les voleurs européens.” [“Banteay Srei, temple restored after a looting of sculptures which caused quite a stir in 1923. It was on this temple that the first reconstruction attempted by the School [EFEO] was carried out, where the stones torn out by the European thieves were put back in place.”

Apocalypse Not Now

For this research, we thoroughly scoured every piece of written and filmed documentation related to Francis Ford Coppola’s magnus opus, Apocalypse Now (1979, with Apocalypse Now Redux released in 2001), and the result is that there is no one mention of Malraux’s adventure in Cambodia, nor of his writings. The personal apocalypsis

As with Coppola decades later, the Malraux couple was under the influence of Joseph Conrad’s overpowering novel, Heart of Darkness (1899, Conrad’s fourth published novel, one year before Lord Jim). Recalls Clara in her memoirs: “On a toujours trop lu. Ma reverie se souvenait — ou pressentait-elle? — de Coeur des ténèbres. Nous aussi allions remonter le fleuve, retourner vers nous-mêmes.” [One always reads too much. My reverie remembered — or did it foresee it? — Heart of Darkness: we too, we would go up the river, travel back to ourselves.”] (Nos vingt ans, Grasset, Les cahiers rouges, 1992, p 90).

Lyotard (op.cit.): “In July 1928, at Pontigny, Malraux confides to Gide, while they stroll beneath the trees in the park: “Conrad is a great mood novelist, in spite of his Flaubertian rhythm. But I must confess my admiration for a lifelong obsession whose origin I cannot put my finger on: that of the irremediable.” [To which Gide responds:] “Verrry innnteresting … As to the question of its origin, I think I can picture it … ” [Malraux throws him a questioning look. Gide takes his arm and, in a diabolical tone of voice:] “Have you ever met Mrs. Conrad?” (ML, 299 – 300) This anecdote is recounted to the French ambassador to Malaysia by a certain Malraux, whom he meets when the latter passes through Singapore in 1965 accompanied by a putative Clappique. The Pontigny scene is set within the Singapore scene, which in turn is set in the theater of 1the Anti-Memoirs-the most well-wrought work by the cubist dressmaker-filmmaker and former forger. As fictive as the (homosexual) “diabolism” attributed to Gide may be, it is no less revealing for what it says about André: women are, like the jungle, figures of the irremediable. After dinner, “Clappique,” inspired by that simultaneously sinister and gay eccentricity worthy of Rameau’s Nephew, unravels for “Malraux” the synopsis of a film on Mayrena, 14 that adventurer who sought to carve himself a kingdom out on the borders of Siam and Cambodia and who lends Malraux inspiration for The Royal Way: ”I’ll have to sort things out with the forest as well. Big problem! A stifling atmosphere, few breaks, Annam a thousand meters below. Swarming everywhere! Villages like pentastomes! Leeches, transparent frogs! A perfectly stripped buffalo skeleton crawling with ants. You get the picture?” [To this, “Malraux”:] “Crystal clear. To me, that’s the forest in

its vastness: insects and spider webs.”

Interestingly, the first script for the epic movie Apocalypse Now, penned in November 1975 by John Milnius before Coppola rewrote it with him (and profoundly changed it), had Kurtz’s wife, ‘Janet’, appear in the last scene. She lives in a California’s neighborhood, “everything good and secure and desirable about America,” as sardonically notes the scriptwriter: “Willard, years later, dressed as a civilian, proceeds past the lawn to the attractive home, carrying a packet under his arm. He passes a lanky, young teen-aged boy working on a motor-scooter. Willard looks at him. The boy looks back. Then the door opens, and Kurtz’s WIFE is standing at the door. She is still beautiful, blonde, and dressed in mourning even though she doesn’t wear black. There is a sense of purity about her, though she is not young.” She wants to know what her late husband’s last words were, and Willard, obviously remembering the haunting whisper-chant — “The Horror! The Horror!” –, lies without lying when he answers: “He spoke of you, m’am”.

The misogynistic theme of the woman-wife-womb as a force preventing the Man to accomplish his destiny in the wild, in the jungle, echoed by Gide’s perfidious remark about “Mrs Conrad” (Jessie George, a typist, a working-class girl sixteen years younger than Joseph) had to appeal to Malraux, whose Voie Royale, first Interallié Prize in 1930, is an archetype of macho literature. Yet he had his wife with him in Banteay Srei, because Clara wanted to be part of the trip and perhaps because the young André wanted to emulate archaeologist Joseph Hackin, who was going to Afghanistan with his spouse — the difference being Mrs Hackin was herself a distinguished archaeologist. And at the stopover in Djibouti in 1923, the Malrauxs visit souks and brothels together [as the Royal Way’s youngest character will do in the novel].

There is possibly an echo of his resentment-admiration-dependence to Clara in Perken’s evocation of his first (and perhaps only) love interest, that enigmatic ‘Sarah’ who was as adventurous, flighty and independent than real-life Clara: “You’ve no idea what it means to be imprisoned in one’s own life; I began to get some inkling of it only

when we parted, Sarah and I. It made no difference to me that whenever a man’s mouth caught her fancy she slept with him (especially during the periods when she was left to herself) — just as she would have followed me, if needs be, to the convict prison — and she’d been through no end of experiences in Siam alter her marriage with Prince Pitsanulok. A woman who knew much of life, nothing of death. One day she saw her life had settled into a groove, become involved in mine. And then she began to loathe the sight of me. as she loathed her mirror. […]Then all the hopes she’d cherished as a girl began, like a dose of syphilis caught in early youth, to eat away her life — and, by contagion, mine as well. You can’t imagine what it means: that feeling of being penned in by destiny, by something you can’t escape or change, something that weighs upon you like a prison regulation; the certainty that you will do this and nothing else, and when you die you will have been that man and no other, and what you haven’t had already you will never have. And all your hopes lie behind you, all those baffled hopes that are flesh of your flesh, as no human being, living or to be born, can ever be.” (RW, p 71 – 2)

While Conrad’s shadow lies heavily on Malraux’s life and writing, there is another literary and larger-than-life figure who haunted him: T.E. Lawrence (16 Aug 1888 — 19 May 1935). But if the author of Seven Pillars of Wisdom remains a beacon of probity — even if not adverse to self-aggrandizement sometimes –, the initial crime in Banteay Srei will forever weigh upon Malraux’s credibility, and may explain he never fulfilled his dream of writing a book about Lawrence. Madsen, who seems to believe the story of young Malraux stumbling upon Lawrence in a Montparnasse gay bar, quotes the great affabulator: ““But mind you,” he says, holding up the index finger of his right hand as an exclamation point, “the difference between Lawrence and me is that he was always sure he would fail whereas I have always believed in the success of my undertakings.”” Even in Banteay Srei, one is tempted to add with dismay.

Olivier Todd (op. cit.): “Malraux stores up literary references, from the Bible to Flaubert and from that adventurer enthroned in unsurpassed legend, the English ex-colonel T. E. Lawrence. If he had seven pillars of wisdom, it’s time for Malraux to build another for himself. He is fascinated by Lawrence and will often repeat the story of his meeting with the colonel in a famous hotel in Paris or in London or on a business trip — anywhere! He has never met Lawrence, but he has imagined him, so it is as if he has — neither true nor false, but “experienced” in the superior reality of historical fantasy. More and more frequently, his truth is catching up with and overtaking reality. He simply has to convince others and then himself, or vice versa. Lawrence also loved archaeology and Dostoevsky and Nietzsche via The Brothers Karamazov and Zarathustra. Gide and Malraux have discussed Dostoevsky many times. Gide feels that “Dostoevsky’s novels, heavy with thought as they can be, are never abstract. They are rich in contradictions, they put mankind on trial.” La Condition humaine also presents a breathless world, judged by communism and terrorism. Malraux’s brief is to change the world by describing it.” […] “Malraux ambles in the garden, strolls along the Promenade des Anglais, and walks around his head, where several projects jostle for attention. He has been amassing documentation on T. E. Lawrence. The preface to his letters is off, but the biography is on again. There are common points and interests between the colonel of Arabia and the coronel of Spain. One is archaeology: here, Lawrence’s abilities outweighed Malraux’s. In La Voie royale, Malraux wrote that “every adventurer is born a mythomaniac.” On the Côte d’Azur, if you don’t join the Resistance, the only available adventure consists of clambering up mountains to find butter, beef, and potatoes. For the moment, Malraux does not want to live on a diet of adventure; better to write someone else’s. Thanks to a certain pride, a contempt for pedantry, and an undeniable talent, Lawrence becomes a character not unlike Malraux. Lawrence studied at Oxford; Malraux imagined he did at the École des Langues Orientales. Geopolitics fascinates them both, and they share a dogged determination to mark History with “scars,” Lawrence in the Middle East, Malraux in Asia and in Spain. They imagine themselves to be, and are, writers and men of action. A love of Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, publicity and mystification, leads them to produce prose that is often tortured. Both are compulsive liars. It’s a toss-up as to which of them is the most depressive. Malraux writes that Lawrence “had, in three years, read four thousand volumes and learned four languages.” A little more than three books a day? These two insatiable spirits, positioned equidistant from literature, war, politics, and sometimes poetry, have one agreeable common trait: they are almost never mean or disdainful. They were both in armored vehicle regiments, Lawrence finishing as an aircraft man in the RAF, Malraux ending his war among “tankers,” without a tank.”

When looking for literary influences on Malraux’s surprisingly detached, almost resentful references to Khmer art, and Cambodia in general, it is not Joseph Conrad or T.E. Lawrence who come to mind but — and Malraux himself would never have acknowledged that — the “dark, demonic” Angkor Wat that obsessed French Christian poet (and Petain’s admirer) Paul Claudel (6 Aug 1868 — 23 Feb 1955) from his visit to Angkor in 1921 to his death. Far from Pierre Loti, who had celebrated the harmony of the Khmer temple fifteen years before Malraux’s expedition, Claudel only perceived in Angkor “cette puanteur hideusement parfumée qui au fond de nos entrailles lie je né sais 7quelle connivence avec notre corruption intime.” Comments Nina Hellerstein in her “Claudel & Angkor Vat : le Feu Divin et Infernal dans le Poete et le Vase d’Encens” (University of Georgia, Paul Claudel Papers vol 5., 2007, pp 27 – 37): “Le poete eprouve dans son propre corps l’écho des péchés de I’Asie, qui sont manifestés sur le plan extérieur par les forces terrifiantes d’une nature démesurée qui a envahi les ruines d’Angkor, et dont la prolifération exprime la menace d’une métaphysique non soumise à la raison structurante judéo-chrétienne. […] Il définit la base de la métaphysique hindoue et bouddhique comme la recherché d’un état de quiétude spirituelle, négatif et destructeur, qu’il identifie avec le non-Etre.” [“The poet experiences in his own body the echo of the sins of Asia, which are manifested on the external plane by the terrifying forces of an excessive nature which has invaded the ruins of Angkor, and whose proliferation expresses the threat of a metaphysics alien to structuring Judeo-Christian reason. […] He defines the basis of Hindu and Buddhist metaphysics as the search for a state of spiritual quietness, negative and destructive, which he identifies with the Non-Being.”] Compare with the iconoclastic fury of the protagonists of The Royal Way: “Only the stone remained, impassive, self-willed as a living creature, able to say “No.” A rush of blind rage swept over Claude and, planting his feet firmly on the ground, he pressed against the block with all his might. In his exasperation he looked round for some object on which to vent his anger. Perken