Lettres du Cambodge, 1947-1950

by Martine de la Ferrière

The coming to age of a young French woman at a transition period for modern Cambodia.

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- Portaparole, Arles, France

- Published

- 2017

- Author

- Martine de la Ferrière

- Pages

- 154

- ISBN

- 978-88-97539-70-4

This delicate yet highly perceptive epistolary novel — based on the correspondence the author actually had with her beloved mother and grandmother, as well as on her personal diary — is the bildungsroman of a young and attractive French administrator’s wife at a time Cambodia was already looking for its independence and feared France and the VIetnamese Emperor were plotting against its territorial integrity.

For the newlywed, wide-eyed but strong-willed woman escaping a France devastated by the war, cold and still submitted to rationing, tropical Cambodia comes across as a little paradise, with a sparkling court life at Phnom Penh Royal Residence where the young King Norodom Sihanouk — he had acceded to the throne six years earlier at the age of 19 — likes to have balls or to go horse riding with joyous guests.

There is a charming scene where the young Frenchwoman and her good-looking friends are enjoying dancing when suddenly the new dress her mother had sent her from France tears at the seams on her lower back — her eager but quite gauche husband has stepped on the dress train, revealing intimate parts of his bride’s anatomy. In haste, she is invited to retreat to the private apartments of the King and gets into one of his night sarongs while “a motherly princess-seamstress, the King’s aunt herself, diligently repaired the damage”. The author does not give a name but we can guess the helpful princess was HRH Samdech Kanitha Rasmi Sobbhana, who was teaching sewing and cooking to the students of the Sutharot Girls High School…

However, life is not always so lush in the Svay Reng posting her husband, “François”– in real life Jacques de la Ferrière, to whom the book is simply dedicated ‘To Jacques’ — has receiving. The young woman has antennas to feel the tension among the French colonials, even if the young administrator does not condescend to share his concerns with his bride, nor explain to her his sudden outings into the countryside. So close to the Vietnamese border, Vietminh incursions are increasing.

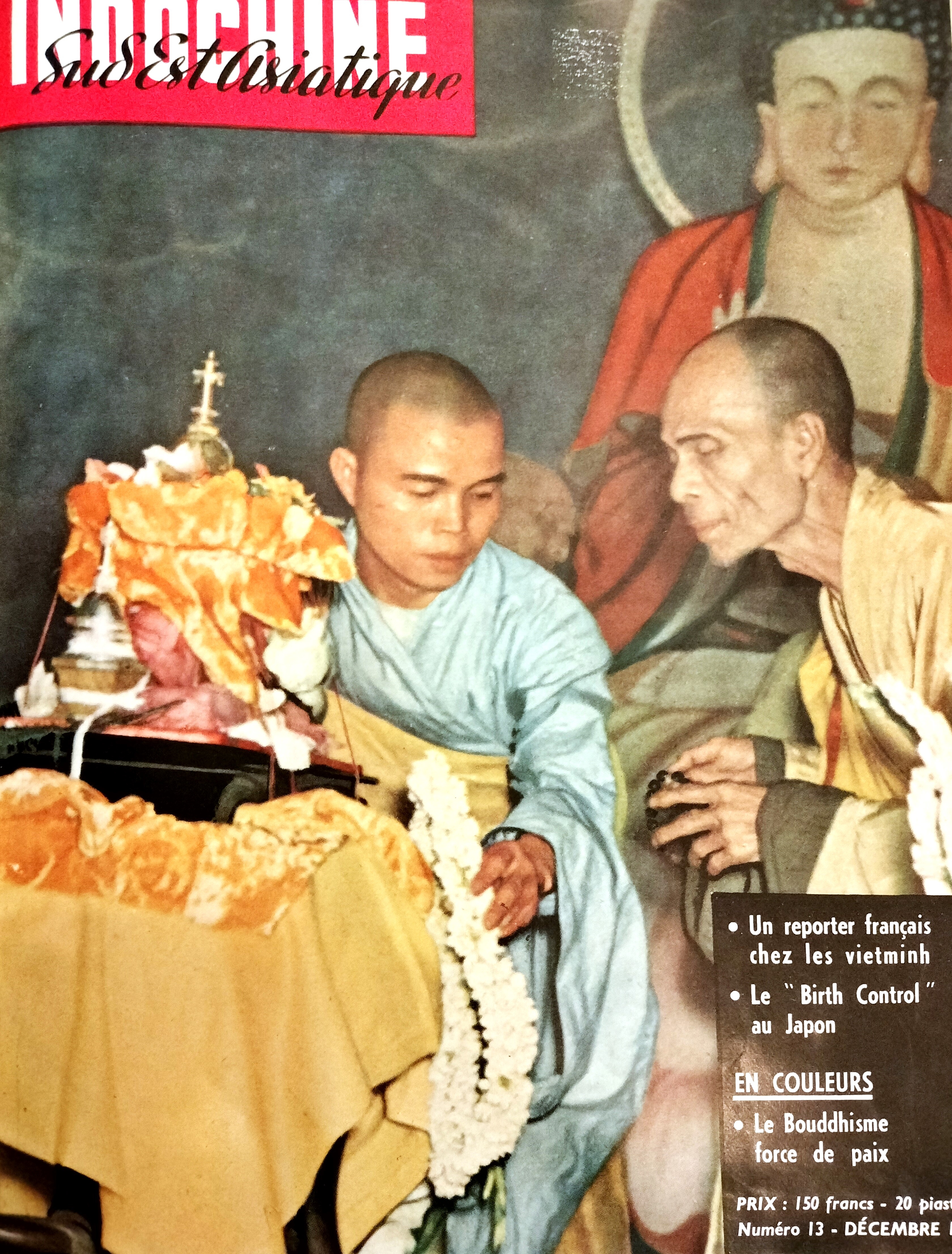

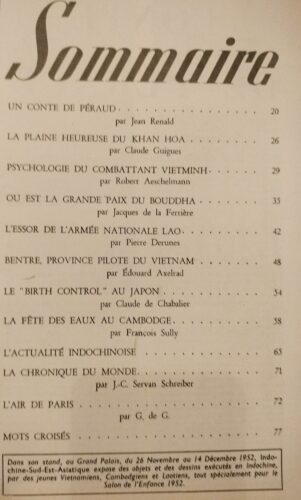

We have found an article Jacques de la Ferrière published in the review Indochine Sud-Est Asie (in December 1950, at the end of his Cambodian posting), in which he shared recollections more candidly than he ever did to his wife. Asking “Where is the Great Peace of the Buddha?”, he wrote: “Je me demande si je né l’ai pas rencontrée au cours d’une de mes pérégrinations cambodgiennes. Il y a quelques années, je suivais un petit commando franco-khmer au coeur d’une région infestée de rebelles. Nous avions effectué une dure progression à travers marécages et buissons bas, aggravés de deux breves et exaspérantes embuscades dont nous nous étions dégagé à grand-peine, sans même voir nos agresseurs. Nous étions épuisés, le coeur plein de déception. Notre haine s’étendait à tous le habitants du pays qui nous semblaient complices de l’ennemi. Le soir tombant, le guide nous proposa de passer la nuit dans une pagode voisine. Il fallut encore nous traîner une heure dans la boue avant d’atteindre ce havre. Enfin, nous vîmes la pointe gris vert des kokis qui ombrageaint le anctuaire. Puis, nous atteignîmes l’avenue que bordait un grand étang où se baignaient silencieusement les bonzes parmi les lotus roses. Nous devions constituer une troupe passablement farouche, mais le Vénérable qui s’avança vers nous pour nous recevoir semblait né pas voir nos armes, pour s’adresser, à travers nos apparences soldatesques, au meilleur de nous-mêmes. Déjà le climat de repos et de beauté du lieu agissait sur nos âmes et sur nos corps comme un baume. Les rayons obliques du soleil couchant glissaient sous le fronton sculpté du temple en allumant un or, en réveillant la lueur rouge d’un ornement. Pas d’autres bruits que ceux d’un couvent franciscain : une clochette de verre caressée par la brise du soir, quelques glissements de pas, des voix feutrées de prière. Des bonzillons nous apportèrent des noix de coco que nous bûmes avidement. Puis, avant de se retirer, le Vénérable nous indiqua le lieu où noua pourrions dormir: une vaste sala au toit de palme, au parquet et aux colonnes de teck ciré. Nous nous y installâmes presque honteusement, avec nos ustensiles de mort, tandis que des demeures des bonzes s’élevaient les litanies rituelles disant la Compassion et la Non Violence. Nous nous endormimes, oubliant la chasse à l’homme. Ce soir-là, je compris ce que signifiait la paix bouddhique…Mais je savais aussi qu’une bande viet1ninh de passage eut été reçue dans les mêmes conditions, avec la même noblesse indifférente. Et pourtant ce que défendait ce petit commando franco-khmer contre les hordes vietminh et leurs commissaires marxistes, c’était un peu l’avenir temporel du bouddhisme, au Cambodge et ailleurs, c’est-à-dire le droit de célébrer le culte…” [‘“I wonder whether I did not encounter that peace during one of my Cambodian wanderings. A few years ago, I followed a small Franco-Khmer commando in the heart of a region infested with rebels. We had carried out a hard progress through swamps and low bushes, worsened by two brief and exasperating ambushes from which we had extricated ourselves with great difficulty, without even seeing our attackers. We were exhausted, our hearts full of disappointment. Our hatred extended to all the inhabitants of the country who seemed to us to be accomplices of the enemy. As evening fell, the guide suggested that we spend the night in a nearby pagoda. We had to drag ourselves another hour in the mud before reaching this haven. Finally, we saw the grey-green tip of the kokis shading the sanctuary. Then we reached the avenue bordered by a large pond where the monks silently bathed among the pink lotuses. We must have formed a fairly menacing band, but the Venerable advanced towards us to receive us, seemingly not seeing our weapons, to reach through our soldierly appearances to the best of us. Already the atmosphere of rest and beauty of the place acted on our souls and our bodies like a balm. The slanting rays of the setting sun slid under the carved pediment of the temple lighting a gold, awakening the red glow of an ornament. No sounds other than those of a Franciscan convent: a glass bell caressed by the evening breeze, a few slipping steps, muffled voices of prayer. Young acolytes brought us coconuts which we drank greedily. Then, before retiring, the Venerable showed us the place where we could sleep: a vast sala with a palm roof, wooden floors and waxed teak columns. We settled ourselves there almost shamefully, with our utensils of death, while from the dwellings of the bonzes rose the ritual litanies saying Compassion and Non-Violence. We fell asleep, forgetting the manhunt. That evening, I understood what Buddhist peace meant… But I also knew that a passing Vietninh band would have been received under the same conditions, with the same indifferent nobility. And yet what this little Franco-Khmer commando defended against the Vietminh hordes and their Marxist commissars was a bit like the temporal future of Buddhism, in Cambodia and elsewhere, that is to say the right to celebrate worship…”]

As a woman, the author is inclined to spontaneously feel that serenity, to stay far away from the “hatred” mentioned by her husband. When the young King and the Minister of the Royal Palace leave all of sudden for France in 1949, nobody tells her they are taking part in hard negotiations with the French and the Vietnamese in order to protect Cambodia’s neutrality. The young woman wishes to know the country better, and above all to see Angkor. Her husband is too busy, too caught into his duties, and she finally drives to Siem Reap with a friend of the couple, “Bertrand”. The magic of the Khmer temples stimulates her senses, her desire to live her life fully before becoming a mother — their son will be born on September 26, 1949, “the same day and in the same maternity ward that King Sihanouk’s consort’s child.” (1) She notes: “Comment né pas fantasmer sur les maisons des favorites, des danseuses royales et leurs musiciens, sur les piscines où de très jeunes femmes aux formes épanouies se baignaient dévetues?” [‘How not to fantasize about the houses of the royal favorites and dancers with their musicians, about the pools where very young women would bathe their buxom, naked bodies?’]

A British explorer met by chance amongst the ruins, “Peter Davies”, will try to pry his way into her room at The Royal Hotel. She laughs away the incident, but she senses that her sexual life has to become more fulfilling. One night, back in Phnom Penh, a few weeks before the return to France, she leaves the marital house “holding my pair of high heels in one hand to be completely silent”, hops in a rickshaw and goes to Bertrand’s, whom her husband likes to call “cet ane de Bertrand” (‘Bertrand the idiot’). Without exchanging a word, they share a moment of pure sexual bliss, and she will proudly explain her motives to her grandmother. She will go on with the social conventions but she has changed, Angkor has changed her.

(1) It must have been HRH Prince (Bhrat Angga Majas) Naradhama Simhahanu Khimanuraksha, son of King Norodom Sihanouk and Princess Bangsangamani, educated in Beijing, married at Khemerin Palace, Phnom Penh, on 20th October 1966, to Anak Munang Surienne (b. 1949), eldest daughter of H.E. San Yun, Akkaraja Maha Mantri, sometime Prime Minister, Minister of the Royal Household, and Director of Services at the Royal Palace, disappeared in September 1976 during the purges of the Khmer Rouge, September 1976, leaving one daughter, H.H. Princess (Anak Angga Majas) Naradhama, b. 1967.

The Dec. 1950 review carrying Jacques de la Ferrière article ‘Où est la grande paix du Buddha’ (courtesy of CKS Library)

Tags: Angkor Wat, women travelers, 1947, Royal Palace, King Norodom Sihanouk Centennial Anniversary, King Norodom Sihanouk, women writers, Indochina War, Buddhism, sexuality, Vietnam, Vietnam War

About the Author

Martine de la Ferrière

Martine de la Ferrière née Péronne (b. 1926, Ile aux Moines, France) is a French writer who published several children’s books, including the Zor Saga, a family autobiography (On n’a pas peur du noir, 2003) and two monographies about her grandfather, the visual artist Jordic (Jordic: un artiste à l’Ile-aux-Moines avant 1914, Blanc Silex, 2004, and Jordic: Biographie, Coetquen, 2009).

In her ‘Lettres du Cambodge’, she recalls in a novelized form the three years she spent in Cambodia with her husband Jacques Gaultier de la Ferrière, who was to become a leading French diplomat, ambassador and France representative to the Atlantic Council. Jacques de la Ferriere was distinguished with the Royal Order of Cambodia in 1950, and later on with the Légion d’honneur. In 2023, Martine de la Ferriere published another personal memory book, Prague comme dans un songe (Coetquen Editions, ISBN 978 – 2849934074)