Music and Musical Thought in Early India

by Lewis Rowell

A sum on early Indian music encompassing the history of thought, religion, science, across the subcontinent.

- Formats

- e-book, on-demand books

- Publisher

- The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, London.

- Edition

- Digital edition: 2015

- Published

- 1992

- Author

- Lewis Rowell

- Pages

- 668

- ISBN

- 978-0-226-73034-9

- DOI

- 10.7208/chicago/9780226730349.001.0001

- Language

- English

This inspired “exercise in musical archaeology” was designed “not only to determine as precisely as possible what we may call the “facts” of music (the tunings, scales, modes, rhythms, gestures, patterns, and formal structures) and the conceptual basis for these facts but also to place these facts and concepts within their proper cultural context and examine their many connections with the fabric of ideas in early Indian philosophy, cosmology, religion, literature, science, and other relevant bodies of thought.”(author’s preface)

It all begins with sound (and silence), the sounds that fill and inform the universe, the sounds that human beings started to organize and develop in order to communicate one with each other, and with the supernatural realms. The book opens with a quotation from the Śākuntala of Kālidāsa, the great Classical Sanskrit poet and playwright (4th – 5th century CE) whose plays and poetry are primarily based on the Vedas, the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata and the Purāṇas (translated by Barbara Stoler Miller):

The water that was first created,

the sacrifice-bearing fire, the priest,

the time-setting sun and moon,

audible space that fills the universe,

what men call nature, the source of all seeds,

the air that living creatures breathe—

through his eight embodied forms,

may Lord Śiva come to bless you!

First, there is the nāda-brahman (usually translated as “causal sound”): “Without nāda, song cannot exist; without nāda, the scale degrees cannot exist; | Without nāda, the dance cannot come into being; for this reason the entire world becomes the embodiment of nāda. | In the form of nāda, Brahmā is said to exist; in the form of nāda, Viṣṇu; | In the form of nāda, Pārvatī; in the form of nāda, Śiva.” Then, intimately linked to Sanskrit and to the cult of Shiva, music as a codified art emerges in early India as saṅgīta, initially “regarded as a composite art consisting of melos (gīta), syllabic accompaniment (vādya), and limb movement (nṛtta, or the more general term nartana [dance]).” Later on, the word was interpreted as “a compound of the implied meanings of the three syllables of the substitute word bharata: bha from bhāva (emotion), ra from rāga (the modal scalar framework for melody), and ta from tāla (the system of hand gestures by which the rhythmic and metric structure of music is controlled and made manifest) (1).”

The purpose of the study is not to analyze the influence of Indian musical system on other cultural entities such as the Khmer Empire. However, it is important to note that at the peak of Indian cultural influence in Southeast Asia, the former had already a long history behind itself. To quote the author’s chronology:

to 2500 B.C. PREHISTORIC PERIOD

2500 – 1750 B.C. INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATIONS

1500 – 500 B.C. ARYAN INVASIONS AND GRADUAL CONQUEST; THE AGE OF VEDIC

1300 – 1000 B.C.; ca. 1000 B.C.; 1000 – 500 B.C.

500 – 300 B.C. THE RISE OF BUDDHISM AND JAINISM

ca. 350 B.C.; 326 B.C.

322 – 185 B.C. THE MAURYAN DYNASTY

272 – 237 B.C.

100 B.C – A.D. 300 THE AGE OF INVASIONS, HINDUISM, AND TANTRISM

500 B.C. – A.D. 500; 400 B.C – A.D. 400; 200 B.C. – A.D. 200

A.D. 320 – 540 THE CLASSICAL GUPTA PERIOD; THE ZENITH OF THE THEATER TRADITION

A.D. 500

A.D. 600‑1200 MEDIEVAL DYNASTIES OE NORTH AND SOUTH INDIA

A.D. 650; A.D. 1100; A.D. 1131

A.D. 1018 MAHMUD OF GHAZNI INVADES INDIA FROM AFGHANISTAN

A.D. 1240; A.D. 1250

From what we know of Ancient Khmer musical forms, the early Indian distinction between mārga (“proper way”, “sacred” music) and deśī (regional, provincial) musical genres certainly applied, and would still work with modern Cambodian music.

The book is probably the most comprehensive study of the main Indian philosophical and technical treatises on music and dance by a non-Indian scholar.

(1) Incidentally, the name of the author of the Natyashastra, one of the most important treatises on music and dance in India, was Bharata Muni (Hindi भरत मुनि), yet in that case it probably refers to the Bharata tribe, as the family name Bharata became common in India. Note also that the idea of calling India as a country “Bharata” emerged in 1950. Barato, the Esperanto name for India, is also a derivation of Bhārata.

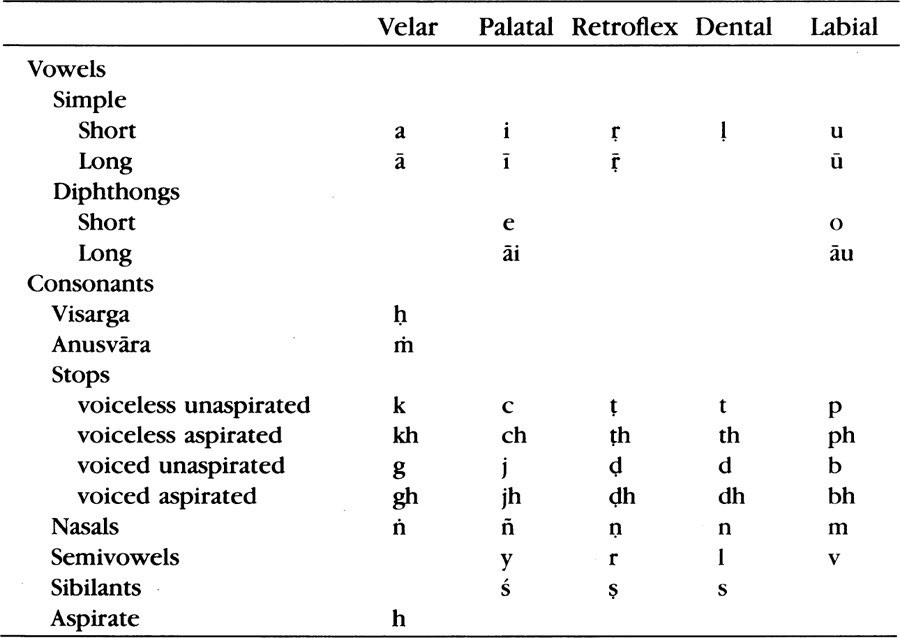

Sanskrit transliteration: pronunciation

The author gives the following guidance for the pronunciation of conventional Sanskrit transliteration:

a as u in but (as in rasa)

ā as in father (as in rāga)

i as in bit

ī as in ravine

u as in put

ū as in rule

ṛ similar to ri in rick

e as ay in hay

ai as in aisle

o as in go

au as ow in cow

c as ch in church but lightly aspirated

ch the same, but aspirated more heavily

g as in game

ñ as in the Spanish word señor

ś as sh in share

ṣ similar to the above

ḥ a rough breathing at the end of a syllable or word (visarga)

ṁ nasalizes the preceding vowel.

In addition, he presents the following table of the 48 Sanskrit morphophomes:

(© Lewis Rowell)

Tags: Indian music, Sanskrit, Sanskrit pronunciation, dance, Indian philosophy, sound, ethnomusicology, Shiva, Khmer music, Indian influences

About the Author

Lewis Rowell

Lewis Rowell (b. 1933) is an American professor of Music and Musicology, a fellow of the American Institute of Indian Studies and the Rockefeller Foundation, and the author of several books and articles on time and rhythm, the music of India, and the philosophy of music.

Prof. Rowell was a faculty research lecturer and a member of the Ethnomusicology and India Studies faculties at Indiana University (Bloomington, Indiana, USA) when he published Music and Musical Thought in Early India (University of Chicago Press, 1992), for which he received the Otto Kinkeldey Award from the American Musicological Society. He has taught musicology and ethnomusicoly at the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, since 1993.