Relations de voyages et textes géographiques arabes, persans et turks

by Gabriel Ferrand

The "Island of Khmer" in the accounts of Arab travelers through the centuries.

- Formats

- e-book, on-demand books

- Publisher

- Documents historiques et geographiques relatifs à l'Indochine, publiés sous la direction de MM. Henri Cordier et Louis Finot | E. Leroux, Paris

- Edition

- e-version by Internet Archive

- Published

- 1913

- Author

- Gabriel Ferrand

- Pages

- 762

- Languages

- French, Arabic

Long before the legendary tales of Sinbad The Sailor — added to the One Thousand and One Nights saga in the 17th-18th centuries –, fearless Arab, Persian and Muslim sailors sailed to the East, attempting to sort out the numerous civilizations distinct from India and China, two formidable entities of which they wanted to fathom the scope and political or cultural influences.

The accounts of travelers and geographers such as Sulayman, Ibn Khordâdzbeh, Ibn Rosteh, Ibn al-Fakih, Ibn Hawkal, al-Yakubi, or the works of the issarak (librarian) of Baghdad Abdul-Faradj Muhammad bin Ishak, trace the emergence of “al-djazair Kmar”, the island or peninsula of Khmer (1), in medieval geography. The author, a distinguished Arabist, translated, collated and compared their accounts.

Among their rich (and often temptative) notations, we shall retain:

Where did India end and the Land of Khmer begin?

- “Le Khmèr (2) fait partie de l’Inde, et les Indiens croient [à tort ou à raison] que leurs livres sont originaires du Khmèr. Ce royaume [de Khmèr] a une étendue de quatre mois [de marche] ; tous [les habitants du pays] adorent les idoles. Le roi de Khmèr entretient quatre mille concubines.” [“The Khmer is part of India, and the Indians believe [rightl or wrongl] that their books originated in the Khmer [country]. This kingdom [of Khmer] has an extent of four months [of walk]; all [the inhabitants of the land] worship idols. The king of Khmer maintains four thousand concubines.”] (p 64)

- “Abu ‘Abdallah Muhammad bin Ishâk raconte que tous les rois de l’Inde, à l’exception du roi de Khmèr’, regardent le libertinage comme licite. J’ai pénétré, [dit-il], dans la ville [du roi de Khmèr] et j’ai demeuré auprès de lui, dans cette ville, pendant deux années. Je n’ai jamais vu un roi plus ennemi du libertinage et plus sévère en matière de boisson ‘, que lui ; car il punit de mort le libertinage et la boisson, il n’y a pas un seul des rois de l’Inde parmi ceux que j’ai fréquentés et auxquels j’ai présenté mes hommages, qui se livre à la boisson, sauf le roi de Babal. On nous a dit que ce dernier, qui est le roi de Ceylan, buvait du vin qu’on lui apportait du pays des Arabes. J’ai vu les marchands de l’Inde et aucun né boit de vin, ni peu ni prou. Ils ont de la répugnance pour le vinaigre de vin; leur vinaigre est fait d’eau de riz cuit qu’on fait aigrir jusqu’à ce quelle soit à l’état de vinaigre. Le musulman qu’ils voient boire du vin, [les gens de l’Inde] le tiennent pour vil, le laissent à l’écart et le méprisent ; et ils disent : ‘Cet homme-là n’a pas de rang dans son pays’. Ce n’est pas par religion, [comme ce serait le cas pour des musulmans] que [les gens de l’Inde] agissent ainsi. L’un d’eux [des musulmans] a dit : « J’étais dans le pays de Khmèr, et on m’apprit que le roi était dur et extrêmement sévère; mais il né fait pas de mal aux Arabes. Quand quelqu’un [des Arabes] pénètre dans son pays, en rémunération du don [du marchand au roi], celui-ci lui donne une chose qui équivaut au centuple du cadeau reçu. Je n’ai jamais vu parmi les rois que j’ai fréquentés, un souverain qui fût plus généreux que le roi de Khmèr. (…)“Dans l’Inde, on dit que les livres de l’Inde proviennent du Khmèr”. L’un des châtiments dont le roi [de Khmèr] punit la boisson [est le suivant :] pour celui de ses généraux et de ses soldats qui boivent du vin, le roi fait chauffer au feu cent anneaux de fer, puis il les fait poser tous sur la main du buveur; il arrive que celui-ci en meurt. C’est un roi très sévère et il n’y en a pas de plus de sévère ni de plus punisseur que lui. Parmi les châtiments qu’il inflige, il y a l’amputation des deux mains, des deux pieds, du nez, des lèvres et des oreilles. II né condamne pas à l’amende comme les autres rois de l’Inde.” [“Abu ‘Abdallah Muhammad bin Ishâk tells that all the kings of India, except the king of Khmer, regard libertinism as lawful. I entered, [he said], in the city [of the king of Khmèr] and I stayed with him, in this city, for two years. I have never seen a king more hostile to licentiousness and more severe in matters of drinking, ‘because he punishes licentiousness with death and drink, there is not a single one of the kings of India among those whom I have frequented and to whom I have paid my respects, who indulges in drink, except the king of Babal. said that the latter, who is the king of Ceylon, drank wine brought to him from the land of the Arabs. I saw the merchants of India and none of them drink wine, little or nothing. loathing for wine vinegar; their vinegar is made of boiled rice water which is soured until it becomes vinegar. The Muslim they see drinking wine, [the people of India] hold it down, leave him aside and despise him; and they say: ‘This man has no rank in his country. It is not out of religion, [as would be the case with Muslims] that [the people of India] do this. One of them [of the Muslims] said: “I was in Khmer’s country, and I was told that the king was harsh and extremely severe; but it does no harm to the Arabs. When someone [of the Arabs] enters his country, in return for the gift [from the merchant to the king], the latter gives him something which is equal to a hundred times the gift received. I have never seen among the kings that I frequented, a sovereign who was more generous than the king of Khmèr. (…) “In India, it is said that the books of India come from the Khmer”. One of the punishments which the king [of Khmer] punishes for drinking [is as follows:] for that of his generals and his soldiers who drink wine, the king fires a hundred iron rings, then he makes them lay all on the drinker’s hand; it happens that the latter dies. He is a very severe king and there is none more punishing than him. Among the punishments he inflicts is the amputation of both hands, both feet, nose, lips and ears. He does not exert fines like the other kings of India.” ] (pp 70 – 71)

- “Le pays de Khmèr est celui d’où sont originaires les dévots; on dit qu’il s’y trouve cent mille dévots. Le roi du Khmèr a quatre-vingts juges. Si un fils du roi se présente devant eux, ils le jugent équitablement [sans tenir compte de sa naissance] et le traitent comme un plaignant ordinaire. [Le souverain du Khmèr] a quatre-vingts mâles, beaux et bien faits, qui sont ses mignons. Vient ensuite le pays de Arman. Les habitants sont beaux; ils marient leurs enfants mâles tout jeunes, et ils prétendent que cela est un bien et les détourne du libertinage. Le roi du Khmèr, malgré sa rigueur [contre les libertins] a l’habitude de dire à ses compagnons : « Quand vous partez en guerre, n’emmenez pas vos femmes ». Il leur a permis, en effet, une fois pour toutes, [d’user] de ce qui appartient à leurs ennemis. [L’auteur] dit : J’ai vu le roi de Khmèr et j’ai vu ‘Âbdï qui est le roi de Ratîlâ’ ; [j’ai vu également] un roi voisin qu’on appelle ‘Arati’ et un roi appelé ‘Saylamân’ qui est plus grand que les deux précédents et qui a une nombreuse armée. On dit que son armée compte environ soixante-dix mille hommes. Il a peu d’éléphants ; mais les gens de l’Inde disent que les éléphants de Saylamân, sont les plus ardents au combat de tous les éléphants de rinde. Je lui ai vu un éléphant appelé namran, et je n’ai vu à aucun roi de l’Inde un éléphant pareil : [il était] blanc, tacheté de noir [et il n’y en a pas] de plus ardent à combattre ni à verser le sang. Le caractère spécial [de ces éléphants de guerre s’explique par les épreuves qu’on leur fait subir avant de les utiliser : on allume un grand feu devant lequel on les amène. Celui [des éléphants] qui ose se lancer dans le feu et passer à travers, est [considéré comme] ardent à combattre et à verser le sang. [L’animal] qui a peur du feu né saurait ni combattre ni servir de monture [de guerre]; on l’utilise alors comme bête de somme, comme les chameaux.” [“The country of Khmer is where the devotees come from; it is said that there are a hundred thousand devotees. The king of Khmer has eighty judges. If a son of the king comes before them, they will him. judge fairly [regardless of his birth] and treat him like an ordinary plaintiff. [The ruler of the Khmer] has eighty handsome and well-made males who are his minions. Next is the land of Arman. The people are beautiful; they marry their very young male children, and they claim that this is a good thing and diverts them from libertinism. The king of the Khmer, despite his harshness [against libertines] is in the habit of saying to his companions: “When you go to war, do not take your wives. ”He allowed them, indeed, once and for all, [to use] what belongs to their enemies. [The author] said: I saw the king of Khmèr and I saw ‘Âbdï who is the king of Ratîlâ’; [I also saw] a neighboring king who is called ‘Arati’ and a king called ‘Saylamân’ who is more gr more than the previous two and which has a large army. It is said that his army numbered about seventy thousand men. He has few elephants; but the people of India say that the elephants of Saylamân, are the most ardent in combat of all the elephants of the rind. I saw him an elephant called namran, and I did not see any king of India like an elephant: [he was] white, spotted with black [and there is none] more ardent to fight nor to shed blood. The special character [of these war elephants is explained by the tests that they are subjected to before using them: a large fire is lit in front of which they are brought. He [of the elephants] who dares to throw himself into the fire and pass through, is [considered] eager to fight and to shed blood. [The animal] that is afraid of fire can neither fight nor serve as a mount [of war]; it is then used as a beast of burden, like camels.”] (p 128)

- “Les récits qui ont cours dans le pays font mention, dans les

temps anciens, d’un roi de Khmèr, pays qui produit l’aloès [appelé] kmâri. Ce pays n’est pas une île; sa situation est [sur le continent indien] du côté qui fait face au pays des Arabes. Aucun royaume né renferme une population plus nombreuse que celui du Khmèr. Tout le monde y va à pied. Les habitants s’interdisent le libertinage, rien d’indécent né se voit dans leur pays et leur empire. Le Khmèr est dans la direction du royaume du Maharâdja et de l’île de Djâwaga. Entre les deux royaumes, il y a dix journées de navigation, en latitude, et un peu plus, en s’élevant jusqu’à vingt journées, quand le vent est faible.” [“Tales told in the country make mention, in ancient times, of a king of Khmèr, a country which produces aloe [called] kmâri. This country is not an island; its location is [on the Indian continent] on the side facing the land of the Arabs. No kingdom has a larger population than that of the Khmer. Everyone goes there on foot. The inhabitants forbid themselves libertinism, nothing indecent is seen in their country and their empire. The Khmer is in the direction of the kingdom of Maharâdja and the island of Djâwaga. Between the two kingdoms, there are ten days of navigation, in latitude, and a little more, rising to twenty days, when the wind is weak.”] (p 85)

The Land of the Aloe

- “Ahmad bin Abi Ya’kûb [al-Yakubi] dit : L’aloès du Khmèr est une espèce qui contient beaucoup d’eau quand il est mûr (?). Ibn Abu Ya’kûb dit : Après l’aloès de Kâkula, vient l’aloès du Campa. On le tire d’un pays appelé Campa, situé dans le voisinage de la Chine. Entre ce pays et la Chine, il y a une montagne infranchissable. C’est le meilleur aloès et celui qui dure le plus longtemps pour les vêtements (sic). Il y a des gens qui le mettent au-dessus de celui de Kâkula. On dit que [l’aloès] du Campa est meilleur, plus parfumé et d’un parfum plus durable. Il en est aussi qui le mettent avant celui du Khmèr.” [kmari] [“Ahmad bin Abi Ya’kûb [al-Yakubi] said: The aloe of Khmer is a species which contains a lot of water when it is ripe (?). Ibn Abi Ya’kûb said: After the aloe of Kâkula, comes the aloe of Campa. It is taken from a country called Campa, located in the vicinity of China. Between this country and China there is an impassable mountain. It is the best aloe and the longest lasting one for clothes (sic). There are people who put it above that of Kâkula. It is said that [the aloe] of Campa is better, more fragrant and of a more lasting fragrance. There are also some who put it before that of the Khmer [kmari].”] (p 85)

- “Abu Dulaf a dit qu’il y a dans l’Inde, au Khmèr, un temple

dont les murs sont en or et dont les plafonds sont en poutres d’aloès indien. Chaque poutre est longue de cinquante coudées ou même plus. Les Buddha, les endroits où on sacrifie et les endroits où on prie, sont incrustés de perles magnifiques et d’énormes corindons. [L’écrivain] dit : Un homme en qui j’ai confiance, dit que les Indiens ont dans la ville de Campa un temple autre que le précédent, que ce temple est ancien et que tous les Buddha qui s’y trouvent entrent en conversation avec les fidèles et répondent à toutes les demandes qu’on leur fait.” [“Abu Dulaf said that there is in India, in Khmer, a temple whose walls are in gold and whose ceilings are made of Indian aloe beams. Each beam is fifty cubits or even longer. The Buddhas, the places where we sacrifice and the places where we pray, are encrusted with magnificent pearls and enormous corundums. [The writer] says: A man whom I trust, says that the Indians have in the city of Campa a temple other than the previous one, that this temple is old and that all Buddhas who are there enter. in conversation with the faithful and respond to all requests made to them.”] (p 123) - “L’Île de Khmer, d’après laquelle l’aloès kmâri porte son nom, a une circonférence d’un mois [de marche]; elle contient beaucoup de villes, peuplées de dévots de la Chine et de l’Inde, et de savants. Un roi nommé Kâmrun y règne. On y trouve une quantité de Buddha et d’idoles comme nulle part ailleurs; les peintres distinguent parmi les représentations des Buddha, le Buddha à regard miséricordieux, ou louchant, ou pleurant, ou riant, ou escamotant. On y trouve une mine d’or, de l’ébène et des paons. L’éléphant y est importé et le rhinocéros y vit aussi.” [“Khmer Island, after which the aloe kmâri bears its name, has a circumference of one month [of walking]; it contains many cities, populated by devotees from China and India, and scholars. A king named Kâmrun reigns there. One finds there a quantity of Buddhas and idols like nowhere else; the painters distinguish among the representations of Buddhas, the Buddha with a merciful gaze, or squinting, or weeping, or laughing , or retreating. There is a gold mine, ebony and peacocks. The elephant is imported there and the rhino lives there too.”] (p 382)

The mysterious Island of WakWak (3)

- “L’île de Wakwâk fait partie de l’ensemble [des îles] Khmèr. Elle n’a pas été ainsi appelée, comme le croit le vulgaire, d’un arbre dont les fruits auraient la forme d’une tête humaine, poussant le cri [de wâk wâk: Wakwâk est son véritable nom]. La couleur du peuple du Khmèr tire sur le blanc; il est de petite taille, ressemble aux Turcs, mais suit la religion des Hindous; ils ont les oreilles percées’. Parmi les habitants de l’île de Wakwâk, il y en a qui sont de couleur noire. Les hommes y sont plus recherchés [que les femmes]. On exporte de chez eux l’ébène noir, qui est le coeur d’un arbre dont on a ôté l’enveloppe.” [“The island of Wakwâk is part of the Khmèr [archipelago]. It was not so called, as the vulgar believe, after a tree and its fruits which would have the shape of a human head and would utter the cry [of wâk wâk: Wakwâk is his real name]. The color of the people of the Khmer draws on white; it is small in size, resembles the Turks, but follows the religion of the Hindus; they have pierced ears. Some of the inhabitants of the island of Wakwâkare black in color. Men are more sought after [than women]. Black ebony is exported from their homes, which is the heart of a tree that we extracted from its envelope.”] (p 345)

- “Pendant son troisième voyage, Sindbâd alla “d’île en île jusqu’à

celle de Salâhal, où l’on trouve du bois de sandal [santal] en abondance”. « Quatrième voyage… Nous né discontinuâmes pas de courir d’île en île, de contrée en contrée, vendant, achetant, échangeant, jusqu’à ce que nous fûmes arrivés dans l’île de Nâkfis, d’oú nous allâmes en six jours à celle de Kalâ»; alors nous pénétrâmes dans le royaume de Kalâ. C’est un grand empire limitrophe de l’Inde, dans lequel il y a des mines d’étain, des plantations de bambous, et où l’on trouve du camphre excellent. Son roi est un monarque puissant; il gouverne aussi l’île de Nâkfis, dans laquelle est une ville appelée également Nâkûs, et qui a deux journées d’étendue » (…)« Cinquième voyage… Nous fîmes voile jusqu’à l’île du Poivre et à l’île de Khmèr dans laquelle se trouve le bois d’aloès nommé canfi et dont les habitants ont horreur de l’adultère et du vin. Après avoir trafiqué là, nous nous rendîmes aux lieux de la pêche aux perles (Hormûz)»” [“During his third voyage, Sinbad went” from island to island as far as that of Salâhal, where sandalwood is found in abundance. ““Fourth journey … We never stopped running from island to island, from country to country, selling, buying, exchanging, until we arrived in the island of Nâkfis, from where we went in six days to that of Kala”; then we entered the kingdom of Kala. It is a great empire bordering India, where there are tin mines, bamboo plantations, and excellent camphor is found. Its king is a mighty monarch; he also rules the island of Nâkfis, in which is a city also called Nâkûs, and which extends for two days of walk”(…)” Fifth journey… We sailed to the island of Pepper and to the island of Khmèr in which the wood aloe is found, named canfi, and whose inhabitants loathe adultery and wine. After having trafficked there, we went to the places of pearl fishing (Hormûz)”.] (p 568)

(1) Contrary to another French Arabist, Guyard, the author translates al-jaza’ir (الجزيرة) as island and not peninsula for Khmer and Champa. The term refers to “land” from a maritime perspective, and for instance Arab authors, including Ibn Khaldoun, named the vast lands — the tip of the African continent, in fact — south of Spain “al-Jaza’ir al-Maghrib”, Island of the Sunset.

2) It must be noted that the etymology of the word Khmer in Arabic is never considered. On the other hand, the author manifests some linguistic knowledge of the Khmer language, for instance when he argues that “the Annamite Nhatrang, là tran, name of a town of Ancient Champa”, derives from “the Cham tran and the Khmer trèn — tall aquatic plants, reeds (Imperata arundinacea).” (p 15)

3) Al-Wakwak (ٱلْوَاق وَاق) is the name of an imaginary island (or archipelago) in medieval Arabic geographical treatises and tales. Some authors believed that Waq-Waq was located in the sea of China, ruled by a queen, and with a strictly female population. Ibn Khordadbeh situateded Waqwaq “east of China, and so rich in gold that the inhabitants make the chains for their dogs and the collars for their monkeys of this metal. They manufacture tunics woven with gold. Excellent ebony wood is found there.” While some Portuguese writers thought of Java as the legendary Wakwak, Michael Jan de Goeje offered an etymology that interpreted it as a rendering of a Cantonese name for Japan. Ferrand identified it with Madagascar, Sumatra or Indonesia, and Tom Hoogervorst thought that that the Malagasy word vahoak, “people, tribe”, was derived from the Malay word awak-awak, “people, crew”.

Full title: Relations de voyages et textes géographiques arabes, persans et turks, relatifs à l’Extrême-Orient du VIIIe au XVIIIe siecles.

email hidden; JavaScript is required

Tags: Arab travelers, geography, India, China, Funan, Chenla, Champa, Wakwak, Sri Lanka, elephants, homosexuality, customs, Arab chroniclers

About the Editor

Gabriel Ferrand

Gabriel Ferrand (22 Jan. 1864, Marseille — 31 Jan. 1935, Paris) was a French orientalist, geographer, linguist, Islamologist and translator who traveled extensively as a diplomat, serving as Consul of France in Madagascar and in Somalia.

At age 18 in 1882, Ferrand joined the Lyon merchant house of Mazeran, Bardey & Cie, and was sent to their branch in the port city of Zeilah, on the Somali coast, specializing in the trade of Abyssinian coffee beans. In Aden, he met famous poet Arthur Rimbaud, who was then working for the Bardey house. His interest in Oriental linguistics developed there, and he came to have a full command of the Somali, Turk, Persian, Malay, Arabic, and Malagasy languages- his 1909 doctoral thesis in Linguistics at Paris University was devoted to a comparative study of Malay and Malagasy phonetics.

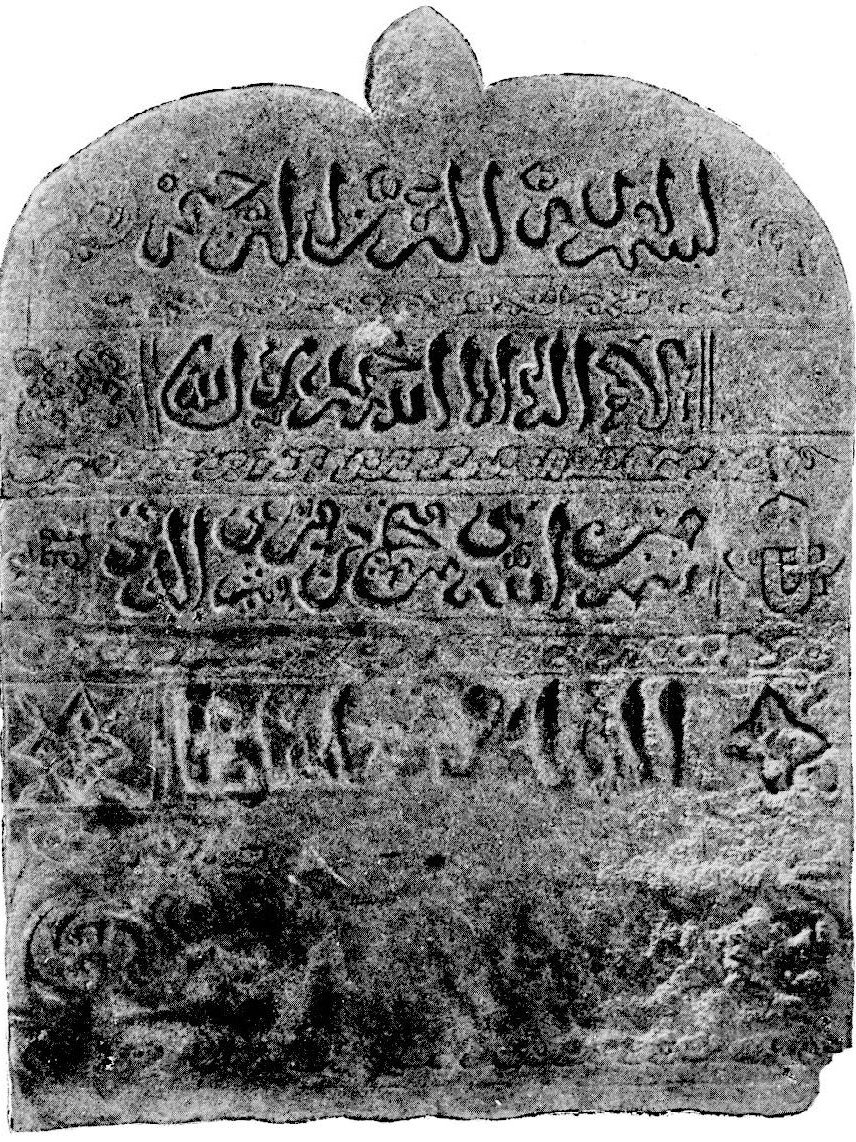

It was as an Arabist that he studied in 1922 the stele written in Arabic discovered at Phnom Bakheng in 1920 by Henri Parmentier, and dated to the 16th century by George Groslier and Victor Goloubew. In BEFEO 22 (1922, 2 p.), he remarked that the Arabic characters “were beautiful and rather modern,” adding that “the scribe seemingly didn’t master Arabic calligraphy, and rather copied a model that had been given to him.” [p 160]

His intellectual curiosity naturally brought Ferrand to the diplomatic career, which started as vice-consul of France in Madagascar (1887−1893) after several years spent in Algiers where he studied Arabic under the supervision of Professor René Basset. He then served as vice-consul in Bender-Bouchir, Persia (1898), in the Kingdom of Siam as consul in Oubon (1899−1902) and chargé d’affaires with the French Legation in Bangkok , again in Persian at Recht, a city on the Caspian Sea shores (1903−1904), Stuttgart, Germany (? — 1913), consul-general in New Orleans (USA) (1915−1919).

A member of Société Géographique de France since 1894, he focused on his scientifc studies from 1920, joining the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) in 1921, corresponding with noted Dutch Orientalists Hendrik Kern and Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, and awarded the Herbert Allen Giles Prize in 1923 by the Société asiatique of Paris for his work L’empire sumatranais de Çrīvijaya.

Editor of Journal Asiatique from 1920 until his death, Ferrand sought in particular to make Arabic geographical and nautical writings more accessible to fellow scholars and students. His Relations de voyages et textes géographiques arabes, first published in 1913 – 14, has seen some 36 republications since.

Publications

[sourced from Nasir Abdoul Carime’s “Biographie de l’AEFEK: Hommage a Gabriel Ferrand” [nd] and other sources]

- “Notes de grammaire somalie”, Bulletin de correspondance africaine, t. 3, 1886 : 492 ‑517. [offprint: Alger : Imprimerie de l’Association Ouvrière, 1886, 28 p.].

- “Notes sur la situation politique, commerciale et religieuse du Pachalik de Harrar et ses dépendances”, Bulletin de la Société de géographie de l’Est, t. 8, 1886, 1st trim. : 1 – 17; 2d trim. : 231 – 244. [Report dated “Alger, 1884” : détails sur la mort de l’explorateur Lucereau, le trafic des esclaves par Abou-Backer, un incident franco-égyptien].

- Les Musulmans à Madagascar et aux îles Comores, 3 vols: 1) Les Antaimorona, 1891, 163 p ; 2) Zafindraminia-Antambahoaka. Onjatsy, Antaiony-Zafikazimambo Antaivandrika et Sahatavy, 1893, vol. 2, 129 p.; 3) Antankarana-Sakalava-Migrations arabes, 1902, vol. 3, 204 p. Paris: E. Leroux.

- [translation, edition and annotation] Contes populaires malgaches, Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1893, 297 p.

- “Généalogies et légendes arabico-malgaches”, Revue de Madagascar 5, 10 May 1902 : 385 – 403.

- La légende de Raminia d’après un manuscrit arabico-malgache de la Bibliothèque nationale”, Journal asiatique (JA), March-Apr. 1902 : 185 – 230.

- “Notes sur la transcription arabico-malgache d’après les manuscrits Antaimorona”, Mémoires de la Société linguistique de Paris, XII, 1902: 141 – 175.

- “Notes de voyage au Guilān”, Bulletin de la Société Géographique d’Alger, t. VII, 1902 : 281 – 320.

- [conference at Ecole Coloniale, 20 May 1903] Les musulmans à Madagascar et aux Iles Comores: Les Tribus musulmanes du Sud-Est de Madagascar, Paris, Impr. de G. de Malherbe, 1903, 22 p.

- “L’élément arabe et souahili en malgache ancien et moderne”, JA 10th series t. 2, 1903 : 451 – 485.

- Les Comâlis, Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1903, 284 p.

- “Les tribus musulmanes du Sud-Est de Madagascar. I”, Revue de Madagascar 6, 10 June 1903 : 481 – 491; II, ibid 7, 10 July 1903 : 3 – 14.

- Essai de grammaire malgache, Paris, Ernst Leroux, 1903, 263 p.

- [tr., revision and annotation] Un texte arabico-malgache du 16e siècle. Transcrit, traduit et annoté d’après les MSS 7 et 8 de la Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, Imprimerie Nationale — Librairie Klincksieck, 1904, 148 p.; also Un texte arabico-malgache ancien, Alger, Ed. Pierre Fontana, 1905, 42 p.

- “Madagascar et les îles Uâq-Uâq”, JA 10th‑3, 1904 : 489 – 510.

- “Qarmathes et Undzatsi”, Revue de Madagascar 11, 10 Nov. 1904 : 408 – 420.

- “Fadi et Totem malgaches”, Revue de Madagascar 5, 10 May 1905 : 385 – 393.

- “Un chapitre d’astrologie arabico-malgache”, JA 10th‑6, 1905 : 193 – 273.

- “Trois étymologies arabico malgaches”, Mémoires de la Société linguistique de Paris, t. XIII, 1905 – 1906 : 413 – 430.

- “Un préfixe nominal en Malgache Sud-Oriental Ancien”, ibid., 1905 – 1906 : 91 – 101.

- “Les migrations juives et musulmanes à Madagascar”, Revue de l’histoire des Religions, LII‑3, Nov.-Dec.1905 : 381 – 417.

- Dictionnaire de la langue de Madagascar d’après l’édition de 1658 et l’histoire de la grande Isle Madagascar de 1661, Paris : E. Leroux, 1905.

- “Un texte arabico-magalche en dialecte sud-oriental : Bibliothèque nationale de Paris, fonds malgache, n° 8”, Recueil de mémoires de textes publié en l’honneur du XIVe Congrès des orientalistes par les professeurs de l’École supérieure des Lettres d’Alger, Alger, Ed. Pierre Fontana, 1905 : 221 – 260.

- Le Dieu malgache Zanahari”, T’oung-pao 1‑VII, 1906 : 123 – 137.

- “Prières et invocations magiques en malgache sud-oriental”, Actes du XIVème congrès international des Orientalistes, Paris, Ernest Leroux, t. II, 1906 : 115 – 146.

- “Le peuplement de Madagascar”, Revue de Madagascar 2, 10 Feb. 1907 : 81 – 91.

- “Contes malgaches”, Revue de Madagascar 4, 10 Apr. 1907 : 199 – 202.

- “Les îles Râmny, Lâmery, Wâḳâḳ, Ḳomor des géographes arabes, et Madagascar”, JA 10th-10, 1907 : 433 – 566.

- “Un vocabulaire malgache-hollandais”, Bijdragen tot de taal‑, land- en volkenkunde, vol. VII, 1908 : 673 – 677.

- “L’origine africaine des Malgaches”, JA 10th-11, 1908 : 353 – 500.

- “Note sur le calendrier malgache et le Fandruana”, Revue des études ethnographiques et sociologiques, 1908 : 93 – 105, 160 – 164, 226 – 241.

- “Le pays de Mangalor et de Mangatsini”, T’oung-pao 1‑X, 1909 : 1 – 16.

- “Note sur l’alphabet arabico-malgache”, Revue internationale d’ethnologie et de linguistique, 1909 : 90 – 206.

- “L’origine africaine des Malgaches”, Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris 10 – 10, 1909 : 22 – 35.

- [doctoral thesis at Université de Paris] Essai de phonétique comparée du malais et des dialectes malgaches, Paris : Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner/Paris : P. Geuthner/Leipzig/O. Harrassowitz; La Haye : M. Nijhoff, 1909, 347 p.

- “Les voyages des Javanais à Madagascar”, JA 10th-15, 1910 : 281 – 330.

“Notes de phonétique malgache”, Mémoires de la Société linguistique de Paris, t. XVII, 1911 – 1912 : 65 – 106. - “Note sur Le Livre des “101 nuits””, JA 10th-17, 1911 : 309 – 318.

- [tr., revision and annotation] Relations de voyages et textes géographiques arabes, persans et turks relatifs à l’Extrême-Orient du VIIIe au XVIIIe siècles, 2 vols., Paris : E. Leroux, 1913 – 1914, 743 p.

- “Ye-tiao, Sseu-tiao et Java”, JA 11th‑8, 1916 : 521 – 530.

- “La plus ancienne mention du nom de l’île de Sumatra”, JA 11th‑9, 1917 : 331 – 335.

- “Malaka, le Malāyu et Malāyur”, JA 11th-11, 1918 : 391 – 484. | “Malaka, le Malāyu et Malāyur (suite) “, JA 11th-12, 1918 : 51 – 154.

- “Le nom de la girafe dans le Ying Yai Cheng Lan”, JA 11th-12, 1918 : 155 – 158.

- “A propos d’une carte javanaise du XVe siècle”, JA 11th-12, 1918 : 158 – 170.

- “Le K’ouen Louen et les anciennes navigations interocéaniques dans les mers du Sud”, JA 11th-13, 1919 : 239 – 333. | [contd.], JA 11th-13, 1919 : 431 – 492. | [contd,] JA 11th-14, 1919 : 5 – 68| [end] JA 11th-14, 1919 : 201 – 241.

- “Samudra et Sumatra”, JA 11th-13, 1919 : 354 – 358.

- “Les poids, mesures et monnaies des mers du Sud aux XVe et XVIIe siècles”, JA, July-Sept.1920 : 1 – 150. | [end] JA , Oct.-Dec. 1920 : 192 – 312.

- [tr., revision and annotation] Instructions nautiques et routiers arabes et portugais des XVe et XVIe siècles, Paris, Librairie orientaliste P. Geuthner, 3 vol., 1921 – 1928: 1/ Le pilote des mers de l’Inde et de la Chine et de l’Indonésie par Shihāb ad-Dīn Aḥmad bin Mājid dit “le lion de la mer”, 1921, 181 p; 2/ Sulaymān al-Mahrī et Ibn Mājid, 1925, 187 p; 3/ Introduction à l’astronomie nautique arabe, 1928, 272 p.

- [tr. from Arabic] Voyage du marchand arabe Sulaymân en Inde et en Chine, rédigé en 851 suivi de remarques par Abū Zayd Ḥasan (vers 916), Paris : Bossard, 1922, 155 p.

- “L’empire sumatranais de Çrīvijaya”, JA 11th-20, 1922 : 1 – 104. [end] JA 11th-20, 1922 : 161 – 246.

- “Une navigation européenne dans l’Océan Indien au XIVe siècle”, JA 11th-20, 1922 : 307 – 309.

- “Le pilote arabe de Vasco de Gama et les instructions nautiques des arabes au XVe siècle”, Annales de Géographie 31 – 172, 1922 : 289 – 307.

- “Notes et mélanges IV. La stèle arabe du Phnoṃ Bakheṅ”, BEFEO XXII, 1922, p. 160 + 1 plate.

- “Notes de géographie orientale”, JA 202, 1923 : 1 – 35.

- “Les instructions nautiques de Sulaymân al-Mahrî (XVIe siècle)”, Annales de Géographie 32 – 178, 1923 : 298 – 312.

- “Notes d’histoire orientale”, Mélanges René Basset. Etudes nord-africaines et orientales, vol. 1, Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1923 : 187 – 208.

- “L’élément persan dans les textes nautiques arabes des XVe et XVIe siècles”, offprint from JA 204, April-June 1924, pp. 193 – 257.

- “Les langues malayo-polynésiennes”, Les Langues du Monde, A. Meillet et M. Cohen eds, Paris, Edouard Champion, 1924 : 405 – 435.

- “Nécrologie, René Basset (1855−1924)”, JA 204, 1924 : 137 – 141.

- “Le Tuḥfat al-albāb de Abū Ḥāmid al-Andalusī al-Ġarnāṭī édité d’après les mss. 2167, 2168, 2170 de la Bibliothèque nationale et le ms. d’Alger”, JA 207, 1925 : 1 – 148. | [end] ibid. : 193 – 304.

- “Les Sultans de Kilwa”, offprint from Publications de l’Institut des Hautes-Études Marocaines vol. 17: Mémorial Henri Basset. Nouvelles Études Nord- Africaines et Orientales, Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1928: 239 – 260.

- “La langue malgache”, Feestbundel uitgegeven door het Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenshappen bij Gelegenheid van zijn 150 Jarig Bestaan, 1778 – 1928, Weltevreden, G. Kolff & Co., vol. I, 1929 : 182 – 186.

- “Les grands rois du monde”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. VI‑2, 1931 : 329 – 339.

- “Quatre textes épigraphiques malayo-sanskrits de Sumatra et de Baṇka”, JA 221, 1932 : 271 – 326.

- “Le Wāḳwāḳ est-il le Japon ?”, JA 220, 1932 : 193 – 243.

- “Géographie et cartographie musulmanes”, Archeion 14, 1932 : 445 – 447.

- “Iranica”, Oriental studies in honour of Cursetji Erachji Pavry, Jal Dastur Cursetji Pavry ed., London, Oxford University Press, 1933 : 123 – 126.

- “Les relations de la Chine avec le Golfe persique avant l’hégire”, Mélanges Gaudefroy-Demombynes : mélanges offerts à Gaudefroy-Demombynes par ses amis et anciens élèves, Le Caire, Impr. de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1935 : 131 – 140.

- “Les monuments de l’Egypte au XIIe siècle d’après Abū Ḥāmid al-Andalusī”, Mélanges Maspero. vol. III : Orient islamique, Le Caire, Impr. de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1935 : 57 – 66.

- [entries in Encyclopédie de l’Islam, 1st ed. (1913 – 1936)] “Madagascar”, “Sayābidja”, “Siam”, “Shihāb al-Dīn”, “Sofāla”, “Sulaimān”, “Zābag “, “Zoṭṭ”.

[photo]: El Alam via Wikipedia