The Angkorian city: From Hariharalaya to Yashodharapura

by Miriam T. Stark & Alison K. Carter & Piphal Heng & Rachna Chhay

An exhaustive update on contemporary archaelogical finds, and what we do know about the urbanistic development of the Angkorian city.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Part of the Catalogue of the exhibition Angkor: Exploring Cambodia’s Sacred City, Asian Civilisations Museum with Guimet Museum, Singapore, 8 April-22 July 2018, ed. Theresa McCullough, Stephen A. Murphy, Pierre Baptiste, Thierry Zéphir

- Published

- 2018

- Authors

- Miriam T. Stark, Alison K. Carter, Piphal Heng & Rachna Chhay

- Pages

- 18

- Language

- English

The study starts with a quite paradoxical (and stimulating) observation: “For pragmatic as well as paradigmatic reasons, Angkor’s archaeological record remains the least understood component of this ancient kingdom’s history. Work by French scholars in the late nineteenth and twentieth century focused primarily on art history, epigraphy, and architecture. More recently, the APSARA Authority and its international partners have worked to conserve and preserve the temples from tourism and encroaching vegetation. (APSARA is the Authority for the Protection of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap, a Cambodian government agency.) Anthropological and archaeological studies of Angkor’s past remain in their infancy. Yet it is precisely such approaches that help us understand the city of Angkor: its biography, its structure, and its inhabitants.”

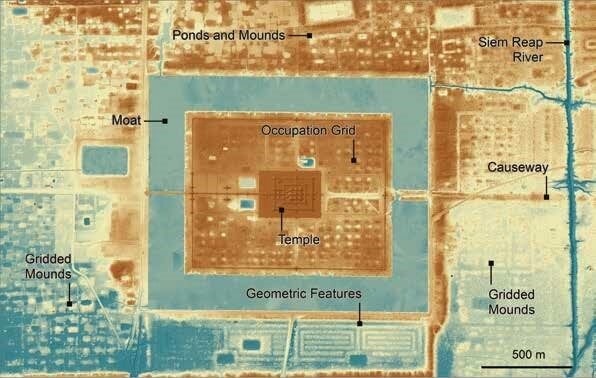

According to the authors, the urbanistic system of Imperial Angkor, especially after what the LIDAR surveys have recently revealed, was based on a “vast water system” that was both “a marvel of engineering and a cautionary tale of technological overreach.”

Assessing the peak era of Angkor, the authors note that “Ta Prohm is but one piece in the rich repertoire that is the monumental legacy of Jayavarman VII. His many temples, bridges, and rest houses are famous for their quantity and their Buddhist iconography and organisation. Yet many would argue that the consolidation of Angkor Thom (Khmer for “Great City”) was this king’s most significant accomplishment. Covering an area of nine square kilometres, with eight-metre-high walls, Angkor Thom enclosed nearly 146 hectares and was surrounded by a 100-metre-wide moat. But this walled area did not define the absolute limits of Angkor Thom. LIDAR data suggest a late twelfth- or thirteenth-century “overflow” of the grid into areas beyond the space delimited by temple enclosures.”

And they conclude: “After more than a century of research, scholars likely all agree that there was no monolithic Angkorian city. Our understanding of Angkorian urbanism changes each time researchers bring new techniques to the field, translate newly discovered inscriptions, and run new field projects that probe both digital and physical limits of our ability to interpret the archaeological record. Within this dynamic context, however, are also continuities in urban structure and morphology. Cambodia in 1200 bore some similarities to Cambodia today. Angkor was a largely ruralsociety, with higher population densities in the 35-square-kilometre civic ceremonial centre. Many Angkorians were farmers, and most of their lives revolved around the temple institution, the maintenance of which absorbed labour and capital, and formed a moral and social ballast for society. Angkorians expected each ruler who ascended the throne to serve his nation and its gods. Rulers varied considerably in their political andideological efficacy; polities waxed and waned; yet the Angkorian state persisted for six centuries on the banks of the Tonle Sap. At its core was always the Angkorian city.”

Read the Catalogue Section

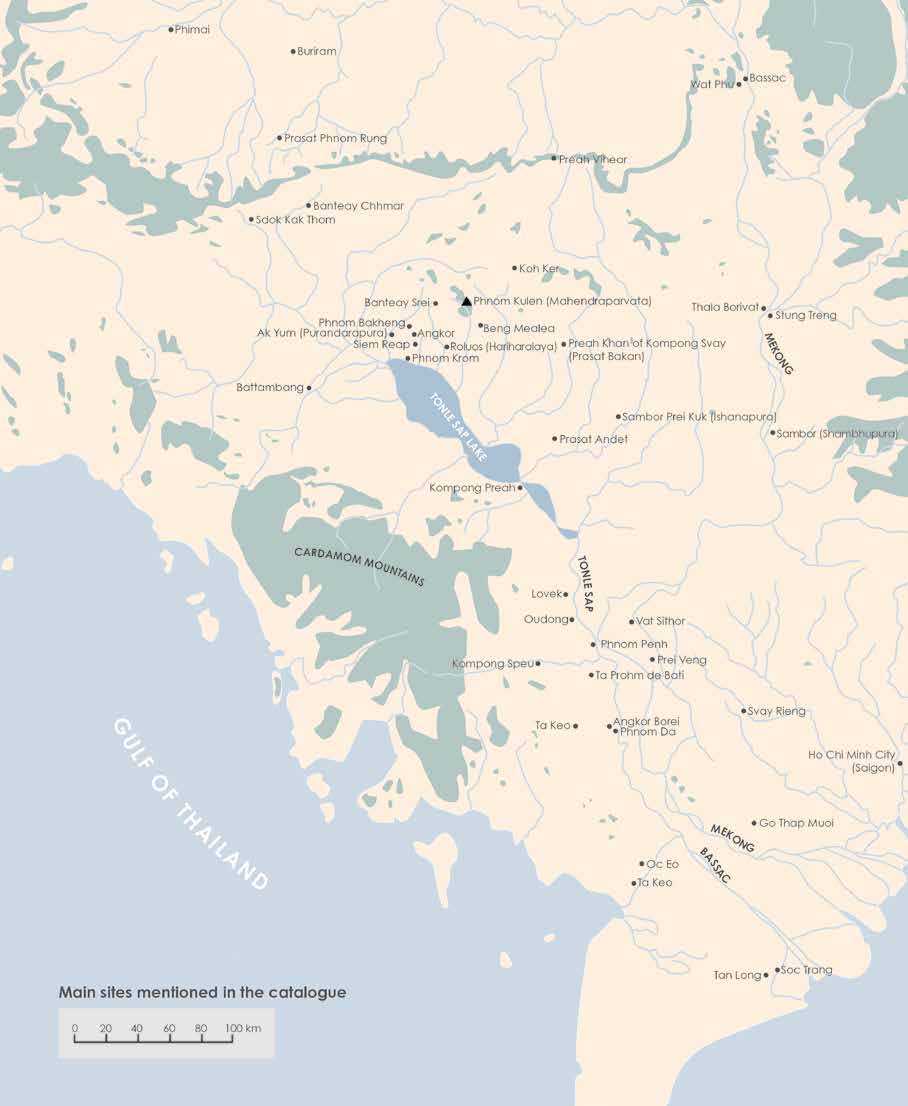

Main sites discussed in the Exhibition Catalogue:

Tags: urbanism, Angkor history, Phnom Kulen, Banteay Srei, Khmer Empire, lidar, anthropology, ceramics, material culture, hydraulic city

About the Authors

Miriam T. Stark

Professor Miriam T. Stark has worked in Southeast Asian archaeology since 1987 and currently directs field-based archaeological research programs in Cambodia that focus on political economy and state formation.

She is a co-director of the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project and a co-investigator with the Greater Angkor Project and the Khmer Production and Exchange Project.

Since 1995, she has taught in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, with specialties in East and Southeast Asian Archaeology and Archaeological Method and Theory.

She also lectured on the AIA’s national circuit Cultural Heritage Policy Committee (2013 – 16 term), focusing on ancient trade networks that linked Southeast Asia to the rest of the Old World, and the origins of Southeast Asian civilizations, with a particular focus on the rise of the Khmer Empire.

Alison K. Carter

An Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Oregon, USA, Alison Kyra Carter researches the political economy and evolution of complex societies in Southeast Asia. Other research interests include the archaeology of East and South Asia, materials analysis and LA‐ICP‐MS, craft technology and specialization, household archaeology, ritual and religion, trade and exchange, and bead studies.

Alison Carter is currently Principal Investigator and Project Co-Director (with Miriam T. Stark) of P’teah Cambodia, an archaeological investigation of Pre-Angkorian, Angkorian, and Post-Angkorian residential spaces in Battambang Province. The project started in May-June 2018 with excavations near Prasat Baset Temple (see project website).

Piphal Heng

Heng Piphal is a Cambodian archaeologist, currently a postdoctoral scholar at UCLA-Cotsen Institute of Archaeology.

After receiving his degree in archaeology from the Cambodia’s Royal University of Fine Arts in 2002, and a MA and PhD degree in Anthropology from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in 2018, Heng Piphal was a ACLS-Robert H. N. Ho postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies & Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University from 2019 to 2021.

His resarchthemes include religious change, urbanism, settlement patterns, political economy, and sociopolitical organizational shift, as well as the intersection between heritage management, collaborative/public archaeology, knowledge production, and urban development.

His current project explores the transformation of urban and rural settlements in response to the demographic and political changes that took place with the adoption of Theravada Buddhism in Angkor (14th-18th century Cambodia).

Rachna Chhay

Chhay Rachna is a Cambodian archaelogist, Head of Ceramic Study Office, International Center of Research and Documentation of Angkor, APSARA Authority, Siem Reap, since 2015.

A specialist in Angkor Ceramics Arts, Chhay Rachna graduated from the Faculty of Archaeology, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in 2002. In 2010, he followed the Luce Asian Archaeology Program Certificate at University of Hawaii-Manoa, and in 2016 the English Language and Academic Studies Programme and International Foundation Courses at SOAS, University of London.