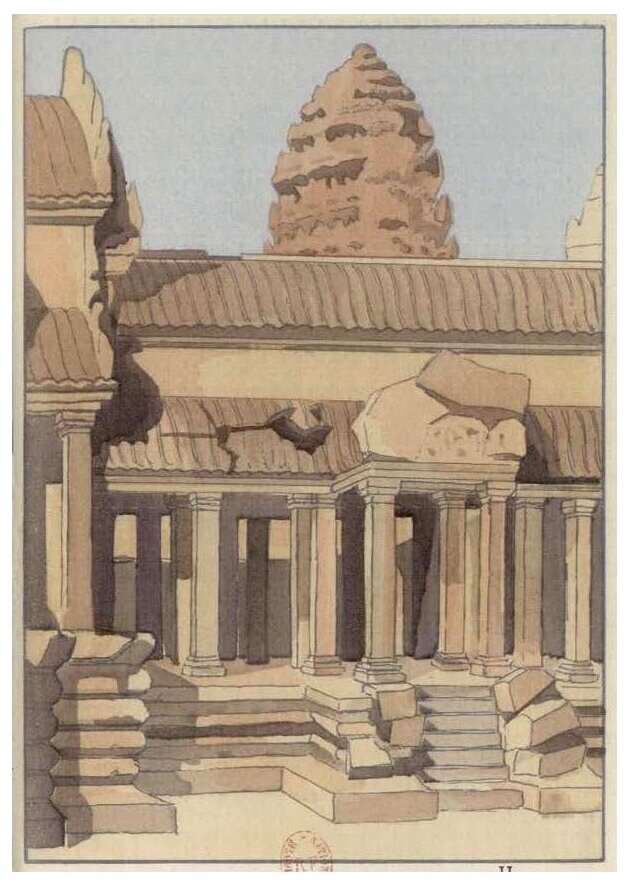

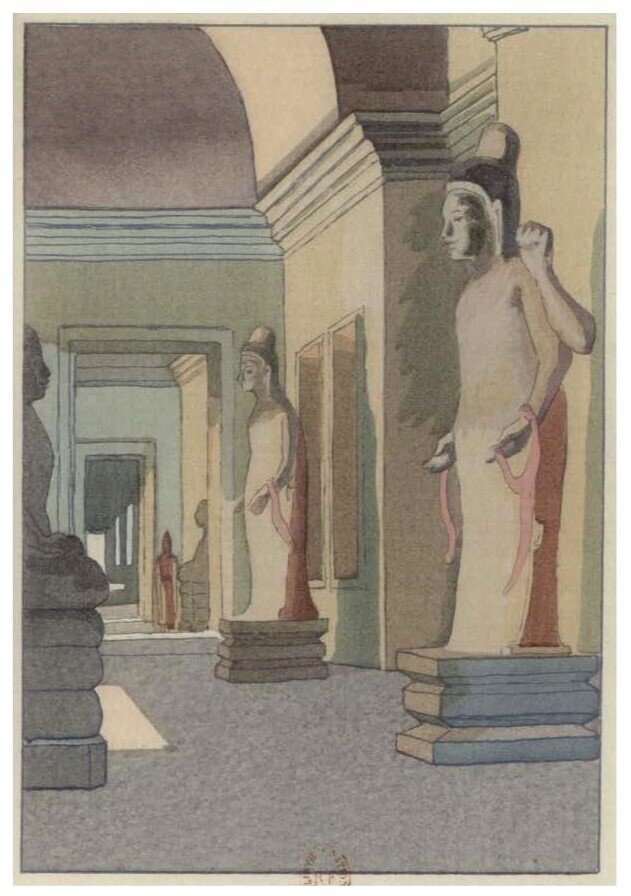

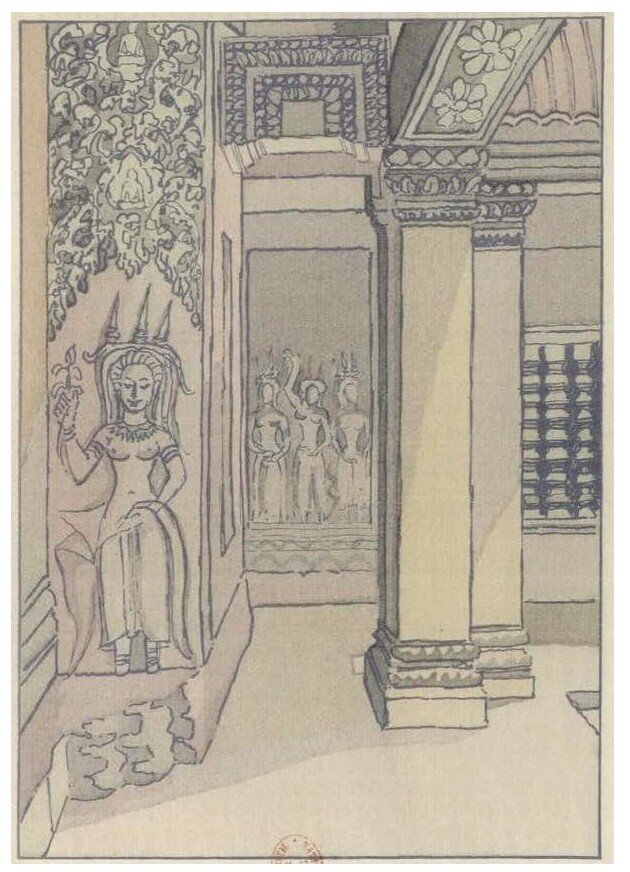

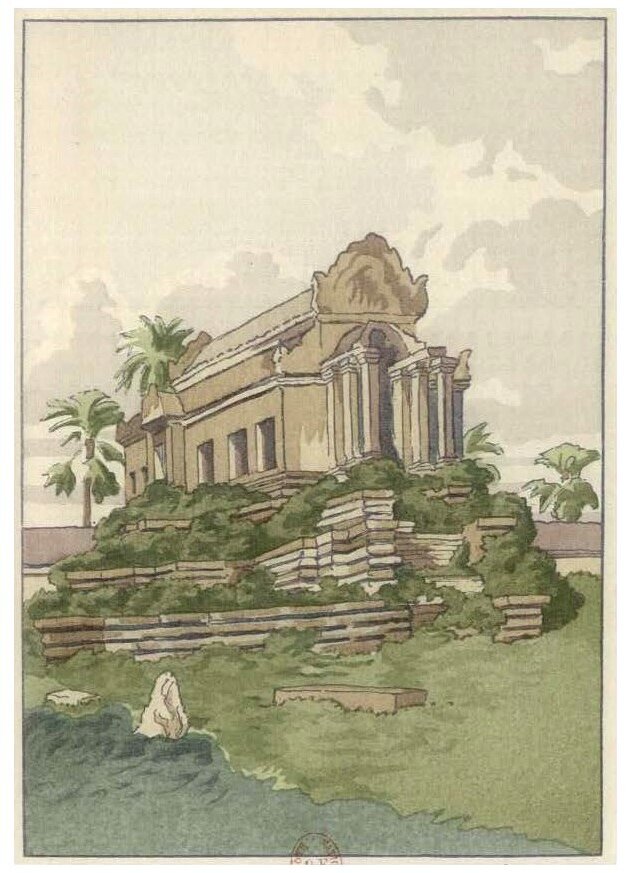

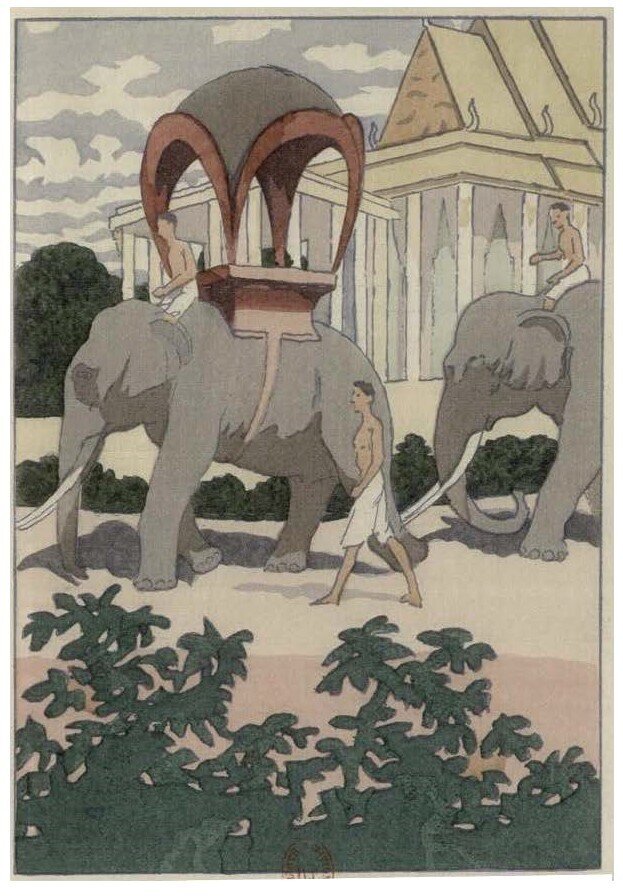

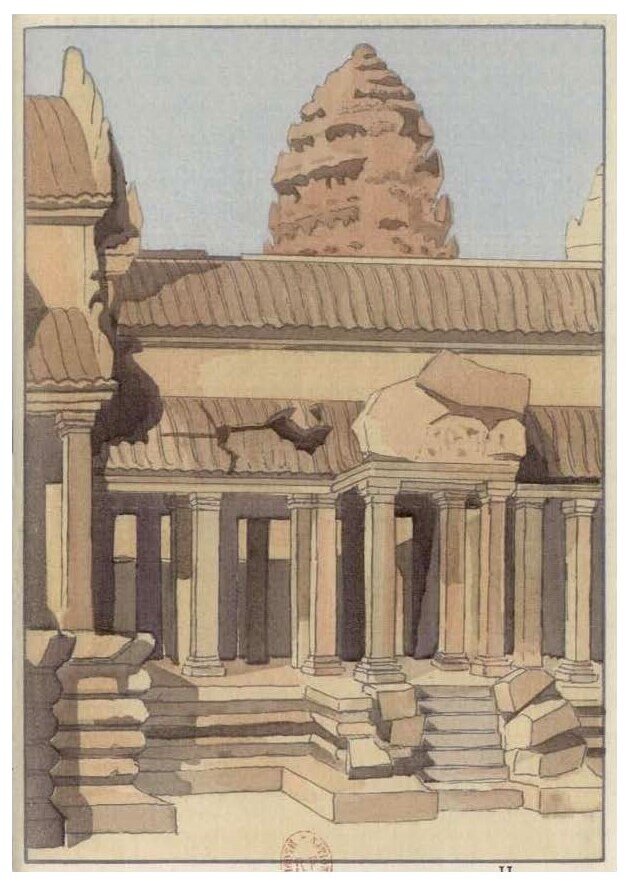

Un pèlerin d'Angkor - Illustré [by Francois de Marliave]

by Pierre Loti

One of the most inspired (and inspirational) travelogues on Angkor in the pioneering times.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Henri Cyral Editeur, Paris.

- Edition

- ebooksgratuits.com, Oct. 2010

- Published

- 1930

- Author

- Pierre Loti

- Pages

- 140

- Language

- French

pdf 4.3 MB

Dedicated to Paul Doumer, then Governor-General of French Indochina, this referential travelogue to Angkor starts with a childhood recollection — the images of Angkor from the pages of an old “colonial review” kept by the author’s in his youth’s “secret museum”, and by an anguished appeal to stop sending troops to Indochina — Loti’s elder brother had been killed in Vietnam, and himself served as a French Navy officer at the time.

What makes the book an enduring evocation of the Khmer temples is probably the writer’s sincere humility , awed by the mystical splendor of the ruins, by their ongoing significance for Cambodian people (monks are ubiquitous in the ancient temples), and convinced of the ultimate futility of the colonial enterprise. It has been said of Loti that he was a master of “the candid and the melancholic”, and these pages prove it. Quite remarkable, out of a body or work in which, according to the great novelist Henry James, “the egotism lives and blooms too, scatters the rarest fragrance and throws out pages like great strange flowers.”

Never attempting to grasp the archaeological intricacies of the site, the author relies more on folk tales about the temples, and on his own feelings when he wanders through the ruins or take a nap in one Angkor Wat gallery. Everywhere, “the discreetly mischievous Apsaras smile at me.” Almost incidentally, we hear about a trio of French archaeologists camping at Angkor Thom. The author meets them by chance, mentions a brief conversation, and abstains to name them, only adding in a footnote that “l’un d’eux, fils d’un célèbre sculpteur français, n’a pas tardé à y mourir de la fièvre des bois” [“one of them, the son of a renowned French sculptor, was soon to die there from the jungle fever”]: Charles Carpeaux, obviously.

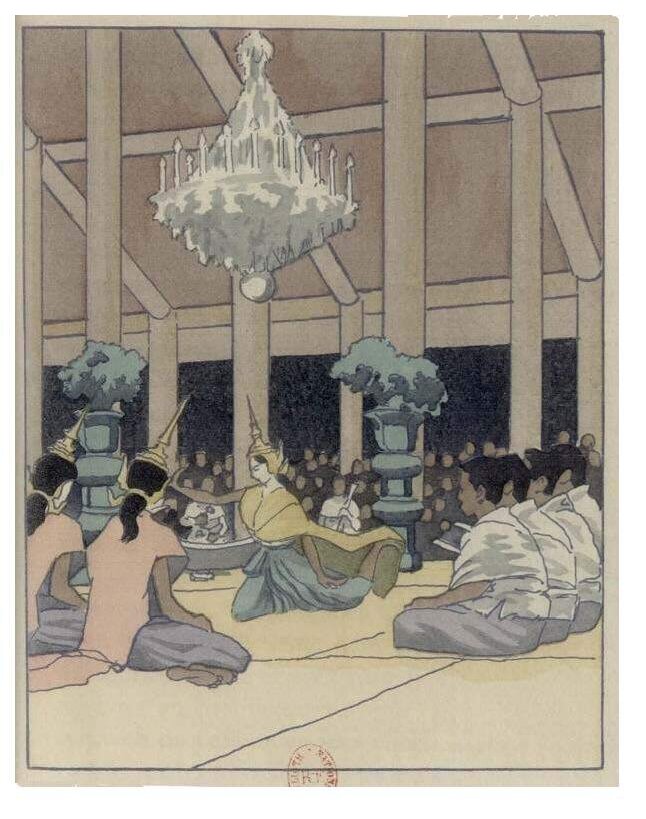

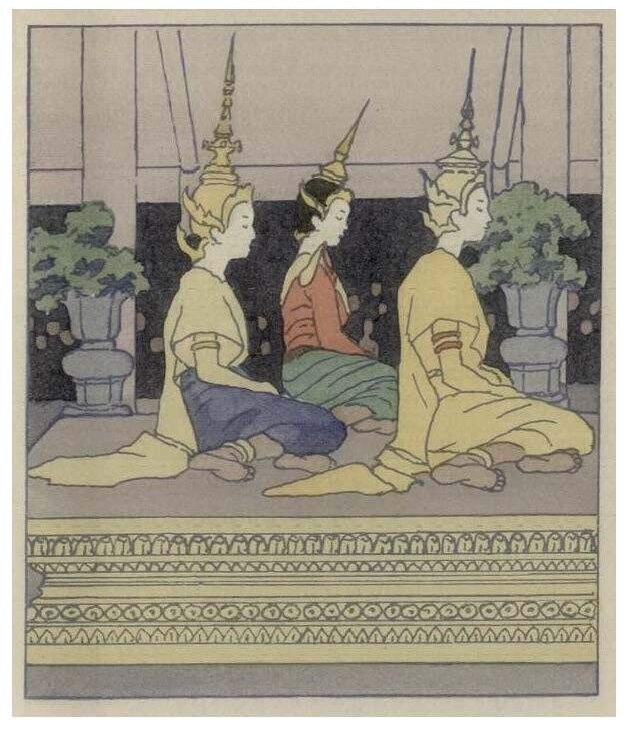

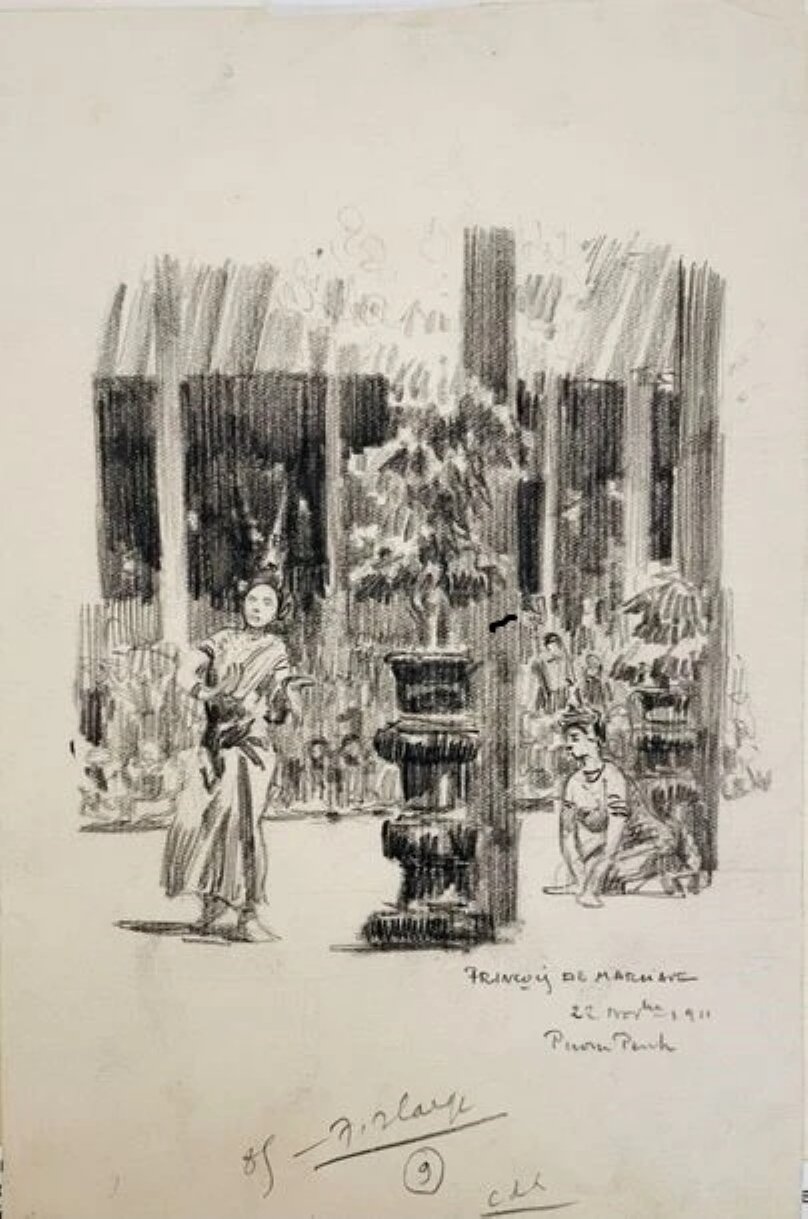

The recounting of his two visits — the first one in November 1901, when Angkor was still in the Cambodian provinces annexed by the Kingdom of Siam, the second in November 1904 –, culminating with an enchanting evening of Khmer royal dancing at Phnom Penh Royal Palace, remains a literary tour de force, expressing what was, to quote Henry James again, “the pure, essential Loti: poetry in observation, felicity in sadness.”

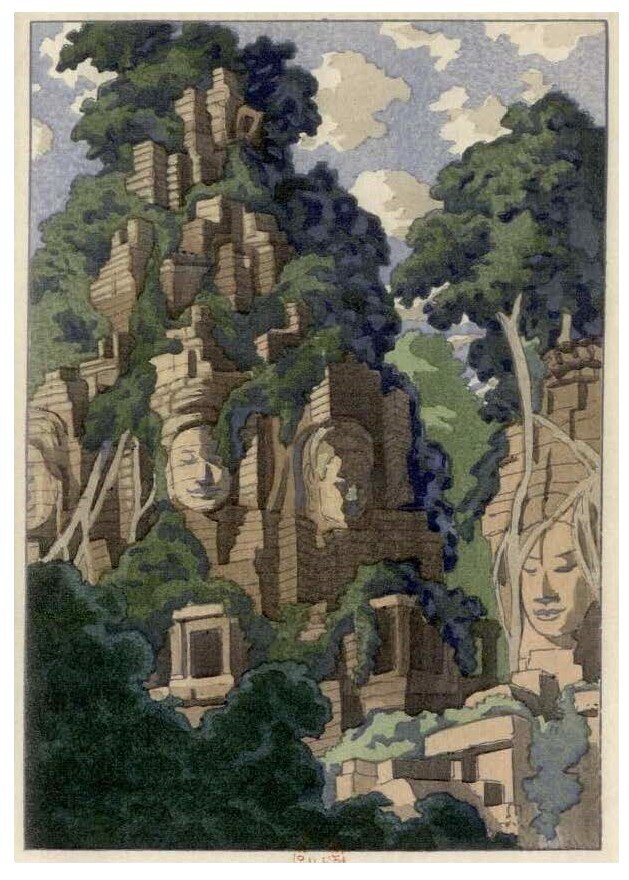

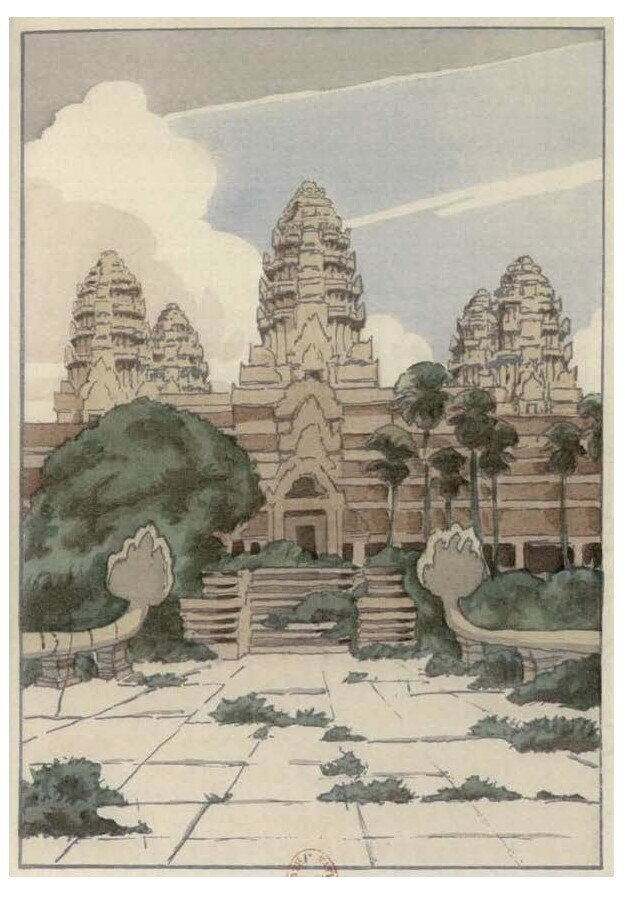

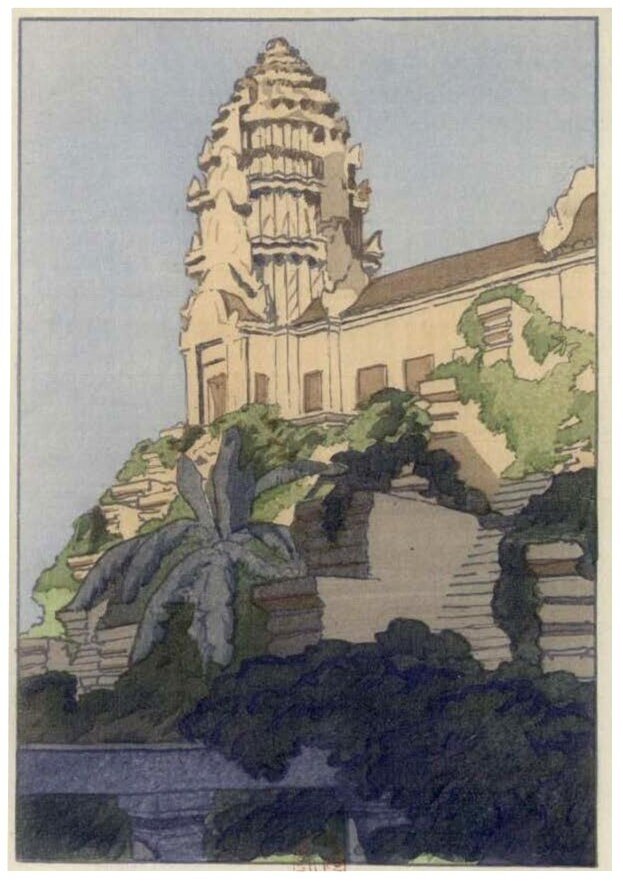

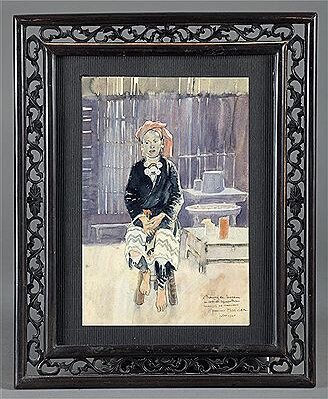

About the illustrator

François Marie Léon de Marliave (10 Oct. 1874, Toulon, France ‑1953, Draguignan, France) was, like Loti, a French navy officer (captain of 2d class aviso “Brandon”) and an artist: ‘peintre-voyageur’ (traveling visual artist) and illustrator.

His career as an established artist spanned from 1904 to his death in 1953. His first destination was French Indochina, visiting Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in 1911 and 1920, in order to create preparatory visuals for the Colonial Exhibitions. The material for Loti’s book was created during his stay in Angkor in November 1920.

He painted and sketched landscapes and people in India (1930), the Middle East (1933−4), and Algeria (1942−5). After Second World War, he drew inspiration from the landscapes of Provence, as he had a residence in Aix-en-Provence since 1917. Some of his works are kept at Musée d’Orsay, section des arts décoratifs, Paris.

That same year, 1930 — seven years after Loti’s death –, another illustrated edition of A Pilgrim of Angkor was published: Pierre Loti, Un pelerin d’Angkor, Paul Jouve and F L Schmied, Paris, illustrations by Jouve, wood engraving by F.L Schmied. That edition is even more striking, Paul Jouve (1878−1973) being a particularly talented visual artist.

Tags: French literature, travelogue, Angkor Wat, dance, music, Royal Ballet of Cambodia, apsara, Apsara dance, royal palaces, Cambodian Royal Ballet, King Norodom I

About the Author

Pierre Loti

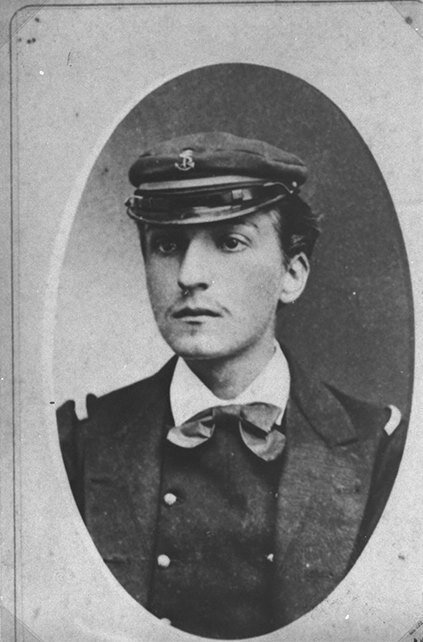

Pierre Loti [born Louis-Marie-Julien Viaud, “Pierre” being a first name suggested by famous actress Sarah Bernhardt and “Loti” the name of an island flower he found in Tahiti] (14 Jan. 1850, Rochefort, France — 10 June, 1923, Hendaye, France) was a French Navy officer, novelist, travel writer, artist, photographer and eccentric art collector who visited Angkor in November 1901, when he was already an established author — he had been elected to Académie Française in 1892 -, publishing Un pélerin d’Angkor [A Pilgrim in Angkor, initially published in English as Siam, 1913] in 1912.

A naval officer serving from 1885 to 1891 on French war ships in China Sea, appointed as ship’s captain in 1906, he became an avid traveler with a fondness for “exoticism”, vising the Middle and Far East, Oceania, North Africa… His first novel, Aziyadé (1879) — which was later interpreted as the hidden account of an homosexual affair -, was an instant success, and his following books settled him as a popular writer: Le Mariage de Loti [originally titled Rarahu] (1880), Le Roman d’un spahi (1881), Pêcheur d’Islande (1886), Madame Chrysanthème (1887), Reflets sur la sombre route (1889), Le livre de la pitié et de la mort (1890), Ramuntcho (1897), Les Désenchantées (1906), Le Roman d’un enfant (1890), Prime Jeunesse (1919), Un jeune officier pauvre (1923)…

The Cahiers Pierre Loti, published in memory of the author from 1952 to 1979 by Association Internationale des Amis de Pierre Loti, claimed that he had always been an “exotic writer, not a colonial writer”, and that he even professed “anti-colonialist” views.His book on Angkor is dedicated to Paul Doumer - former General-Governor of Indochina and Loti’s close friend who had organized his 1901 trip to Angkor -, to whom he wrote: “Will you forgive me for having said that our Empire in Indo-China would lack grandeur and, more especially, would lack stability — you who have worked so gloriously and so patiently to ensure its permanence ? But so it is. I do not believe in the future of our distant colonial conquests. And I mourn the thousands and thousands of our brave little soldiers, who, before your arrival, were buried in those Asiatic cemeteries, when we might so well have spared their precious lives, and risked them only in the last defence of our beloved French land.”[p vii-viii]

Married to wealthy heiress Jeanne Amélie Blanche Franc de Ferrière — who eventually left him as he kept a mistress, Crucita Gainza [“my Basque wife”], with whom he had three children –, Loti gathered an astonishing collection of artworks, souvenirs, rarities such as sperm whale teeth, Egyptian cat mummies or Ottoman coffins, part of which is kept at the Maison Pierre Loti museum in Rochefort.

1) Julien Vaud (Pierre Loti) amongst his family in 1855 (source: gallica.bnf.fr). 2) Pierre Loti at home, c. 1892.

In his foreword to Impressions by Pierre Loti (Archibald Constable & Co., Westminster, 1898), novelist Henry James wrote: “He is extremely unequal and extremely imperfect. He is familiar with both ends of the scale of taste. I am not sure even that on the whole his talent has gained with experience as much as was to have been expected, that his earlier years have not been those in which he was most to endear himself. But these things have made little difference to a reader so committed to an affection.(…) I read and relish him whenever he appears, but his earlier things are those to which I most return. It took some time, in those years, quite to make him out he was so strange a mixture for readers of our tradition. He was a ” sailor-man” and yet a poet, a poet and yet a sailorman.(…) He has not been an explorer and is not of that race, but his perception so penetrates that he has only to take me round the corner to give me the sense of exploring. I have been assured that Madame Chrysantheme is as preposterous, as benighted a picture of Japan as if astranger, disembarking at Liverpool, had confined his acquaintance with England to a few weeks spent in disreputable female society in a vulgar suburb of that city. (…) Loti belongs to the precious few who are not afraid of being ridiculous; a condition not in itself perhaps constituting positive wealth, but speedily raised to that value when the naught in question is on the right side of certain other figures. His attitude is that whatever, on the spot and in the connection, he may happen to feel is suggestive, interesting and human, so that his duty with regard to it can only be essentially to utter it. The duty of not being ridiculous is one to which too many travellers of our own race assign the high position that he attributes to right expression, to right expression alone.(…) That is pure, essential Loti — poetry in observation, felicity in sadness.”

Two portraits of Pierre Loti at different ages [source: gallica.bnf.fr]

Publications

- Aziyadé (Stamboul 1876 – 1877) [anonym, presented as notes from an English officer killed in Turkey on 17 October 1877], 1879.

- Le Mariage de Loti [written in 1872, published with mention “par l’auteur d’Aziyadé” with the title Rarahu in 1880], 1882 [first book published by Calmann-Lévy, Paris, as well as most of the following ones].

- Le Roman d’un spahi, 1882.

- Fleurs d’ennui [short stories collection : Pasquala Ivanovitch, Suleïma, Voyage au Monténégro], 1883.

- Trois journées de guerre en Annam, 1883.

- Mon frère Yves, 1883.

- Les Trois Dames de la Kasbah, 1884.

- Pagodes souterraines, 1884.

- Pêcheur d’Islande, 1886.

- Madame Chrysanthème, 1887.

- Propos d’exil, 1888.

- Japoneries d’automne, 1889.

- Au Maroc, 1889.

- Le Roman d’un enfant, 1890.

- [preface to] Qui frappé? by Carmen Sylva, 1890.

- Le Livre de la pitié et de la mort, 1891.

- Fantôme d’Orient [derived from Aziyadé], 1891.

- Constantinople en 1890, 1892.

- Matelot, 1892.

- Discours de réception à l’ Académie française, 1892.

- L’Exilée, 1893.

- [preface to] Du côté de chez nous by Frédéric Arthur Chassériau (1865−1955), 1893.

- La Grotte d’Isturitz, 1895.

- Le Désert, 1895.

- Jérusalem, 1895.

- La Galilée, 1896.

- La Mosquée verte, 1896.

- Ramuntcho, 1897.

- Figures et choses qui passaient, 1897.

- Judith Renaudin, 1898.

- L’Île du rêve, 1898.

- Rapport sur les prix de vertu, 1898.

- [preface to] Les glanes de la vie by Comtesse Diane, Ollendorf, 1898.

- Reflets sur la sombre route, 1899.

- [preface to] Deuil de fils by Frédéric Arthur Chassériau, Ollendorf, 1899.

- [preface to] Lumières d’Orient by Émile Vedel, Ollendorf, 1901.

- Les Derniers Jours de Pékin, 1902.

- L’Inde (sans les Anglais), 1903.

- Vers Ispahan, 1904.

- [tr. with Émile Vedel] Le Roi Lear, Shakespeare, 1904.

- La Troisième Jeunesse de Madame Prune, 1905.

- Les Désenchantées, roman des harems turcs contemporains, 1906.

- Vies de deux chattes, 1907.

- Ramuntcho [theater play], 1908.

- La Mort de Philae, 1909.

- Les pagodes d’or, 1909.

- Le Château de la Belle-au-Bois-Dormant, 1910.

- Pêcheur d’Islande [theater play], 1911.

- La Fille du ciel, drame chinois [theater play with Judith Gauthier], 1911.

- [preface to] Poésies d’un marin by Eugène de Fauque de Jonquières, 1911.

- Un pèlerin d’Angkor, 1912; English ed.: Siam, translated from the French by W. P. Baines, illustrated with photographs and an etching by Edith M. Hinchley, T. Werner Laurie Publishers, London, 1913, and Philadelphia, David McKay, 1914; reissued 1930, with illustrations by F. de Marliave, Paris, Henri Cyral.

- [preface to] Les deux rêves by Justin Massé, 1912.

- Turquie agonisante, 1913.

- La Grande Barbarie, 1915.

- À Soissons, 1915.

- La Hyène enragée, 1916.

- Quelques aspects du vertige mondial, 1917.

- L’Outrage des barbares, 1917.

- Court intermède de charme au milieu de l’horreur, 1918.

- L’Horreur allemande, 1918.

- Les Massacres d’Arménie, 1918.

- Les Alliés qu’il nous faudrait, 1919.

- Mon premier grand chagrin, 1919.

- Prime Jeunesse, 1920.

- La Mort de notre chère France en Orient, 1920.

- Suprêmes visions d’Orient [with son Samuel Viaud], 1921.

- Un jeune officier pauvre [extracts of P.L.‘s journal published by Samuel Vaud], 1923.

- Journal intime, 1878 – 1881, 1st part, [also series in L’Illustration], 1925.

- La maison des aïeules suivi de Mademoiselle Anna très humble poupée, illustr. by André Hellé, 1927.

- Journal intime, 1882 – 1885, 2d part, 2 vol. with unpublished letters 1865 – 1904, 1929 [posthumous]; reiss. as a)

Cette éternelle nostalgie, journal intime, extraits (1878−1911), Paris, La Table Ronde, 1997; b) Soldats bleus, journal intime, 1914 – 1918, Paris, La Table Ronde, 1998. c) Unabridged edition: Journal intime 1868 – 1878, t. I, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, Paris, Les Indes savantes, 2006; Journal intime 1879 – 1886, t. II, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, id., 2008; Journal intime 1887 – 1895, t. III, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, Paris, id., 2012; Journal intime 1896 – 1902, t. IV, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, id., 2016; Journal intime 1903 – 1913, t. V, éd. Alain Quella-Villéger, Bruno Vercier, id., 2017.