Lucille Douglass' Drawings for New Journeys in Old Asia

by Lucille Sinclair Douglass

A series of etchings made by an American female artist discovering Cambodia and Asia in the 1920s.

In 1926, American visual artist Lucille Douglass visited the ancient Cambodian ruins at Angkor for the first time. According to researcher Stephen Goldfarb [1] [in a piece for Alabama Heritage magazine reproduced on Devata.org],

That December the forty-eight-year-old artist wrote to her friend Leona Caldwell of her first impressions of this far-off and exotic place: “Angkor is one of the really great experiences of my life‑a more intellectual than emotional experience — not that it left me cold, quite the contrary — but it was more of an uplift — an inspiration. “Our stay — longer than most tourists — was all too short — Angkor Wat alone requires years of study — living with understanding — a few days seems but a mockery. “I have never had a place affect me so peculiarly.… I shall go back for a time as long as I can stand it and do further study on the spot. “You see the ruins are set in the midst of the jungle — which held them in its clutches for so many centuries that it still seems jealous of them.”

Douglass described the Angkor climate as “the most trying [that] I have ever encountered … [with its] great humidity and high temperatures — an oppressive heaviness which brought all the moisture to the surface [of one’s skin] and left you exhausted with the slightest effort.” And this complaint comes from a woman who grew up in central Alabama.

She was then a confirmed artist, having traveled around Europe and North Africa and exhibited in Paris, but had suffered a breakdown after nursing soldiers back in America during World War I. Then, to quote Goldfarb (op. cit.),

Her life took a fresh turn in 1920, when the forty-two-year-old Douglass accepted a position with the Methodist Missionary Society. She was employed to oversee a workshop in Shanghai in which Chinese women hand-colored an early form of photographic slide used by speakers to publicize the missionary work of the society. The job did not absorb all of her time and energy apparently, for she became first a writer and then associate editor of the weekly English-language publication, Shanghai Times, a position she held until 1924. During these years she traveled extensively in China as a member of the press. These trips were often dangerous, as China was in the midst of revolution and civil war.

In China, Lucille Douglass befriended two female writers, Florence Wheelock Ayscough, who wrote extensively about China, and Helen Churchill Candee, who invited her to join her in a new trip to Siam, Tonkin and Angkor. She had described the Khmer ruins in Angkor The Magnificent (1924), and asked the artist to illustrate her second visit, narrated in New Journeys in Old Asia (1927).

List of illustrations

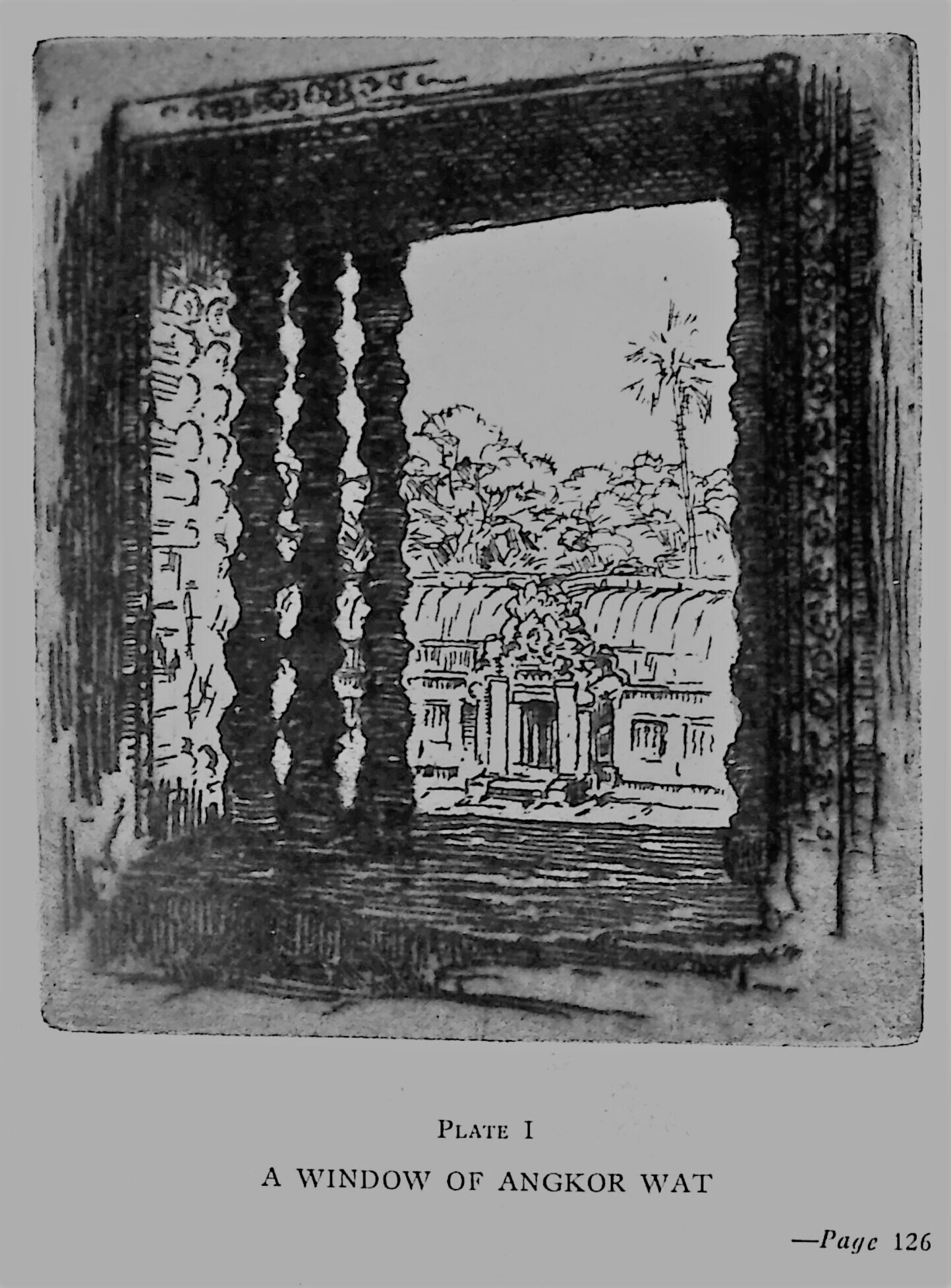

- PIate I. A Window of Angkor Wat | frontispiece

- Plate II. Colourful Craft in Hong-Kong Harbour | facing page 2

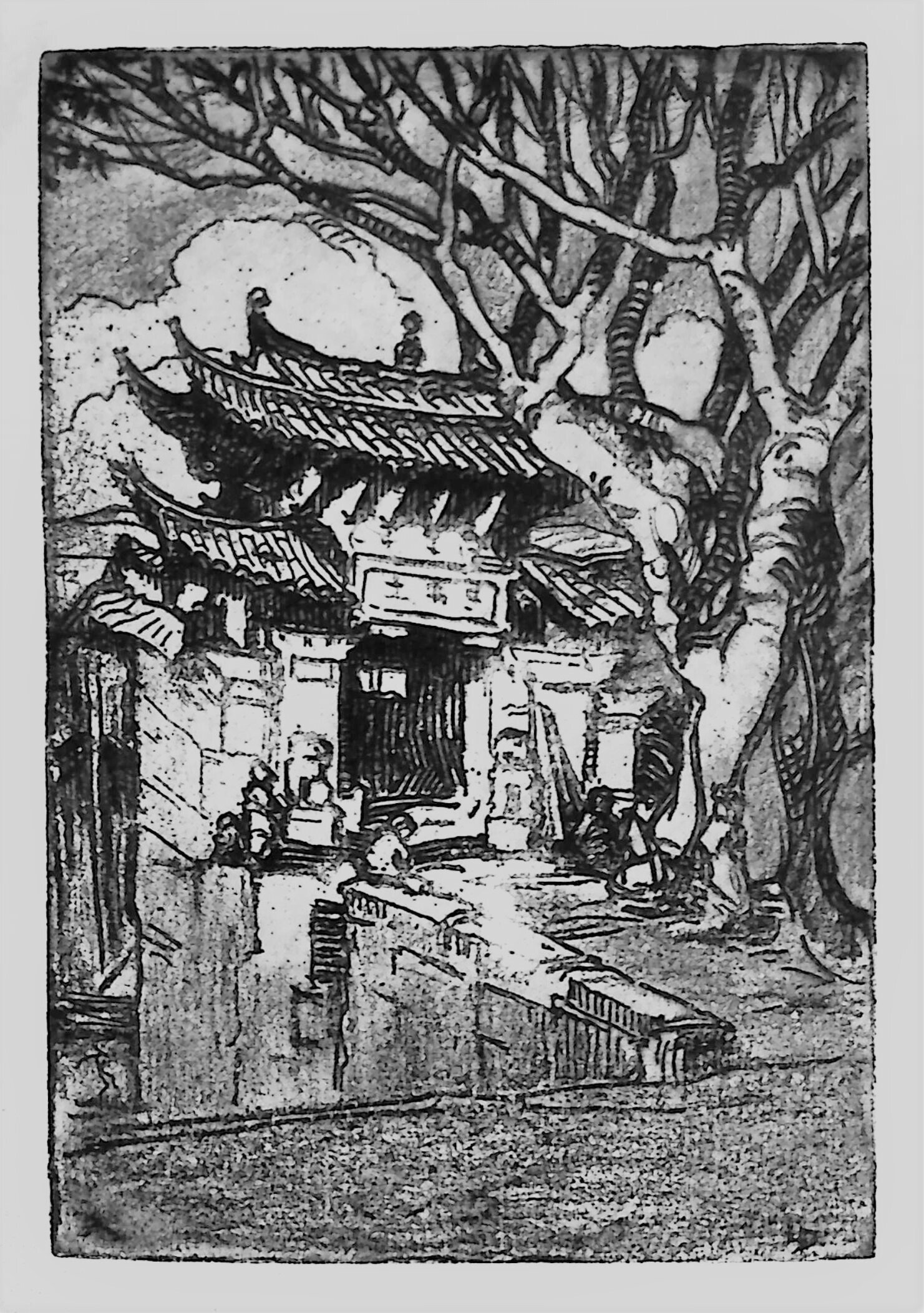

- Plate III. The Gate to Yunnan-Fu | fp 10

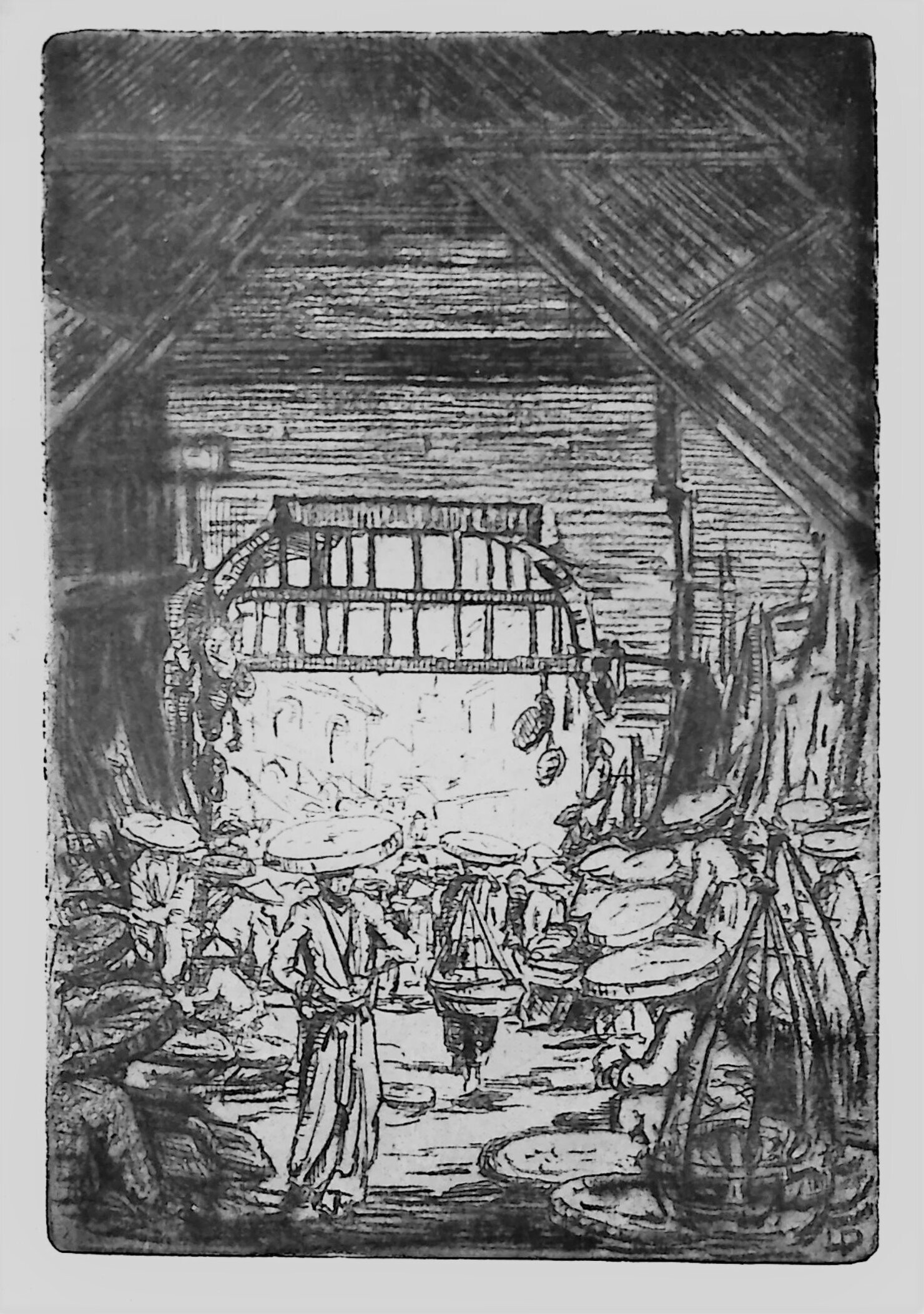

- Plate IV. A Market Scene in Tonkin| fp 16

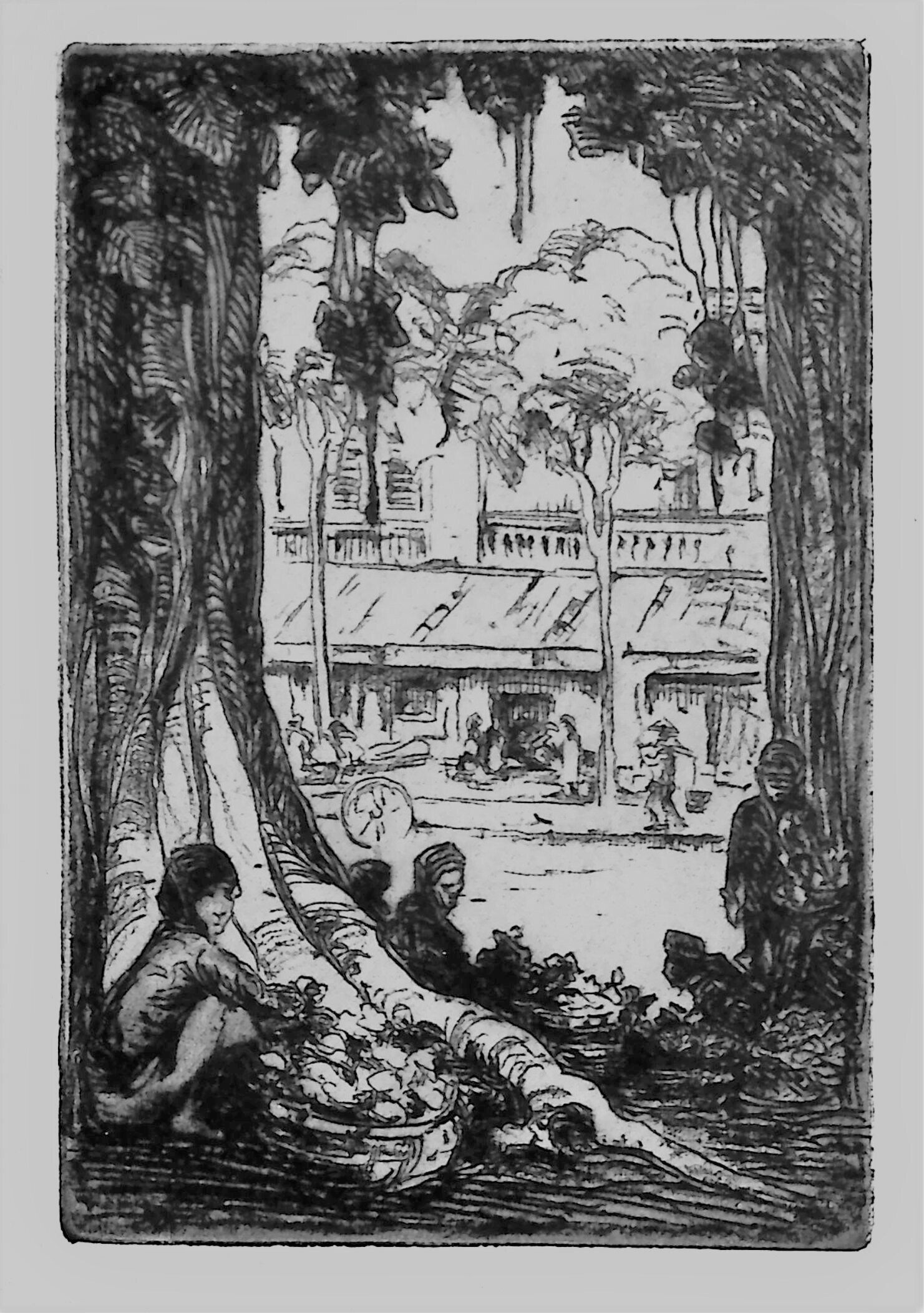

- Plate V. The Flower Market at Hanoi | fp 28

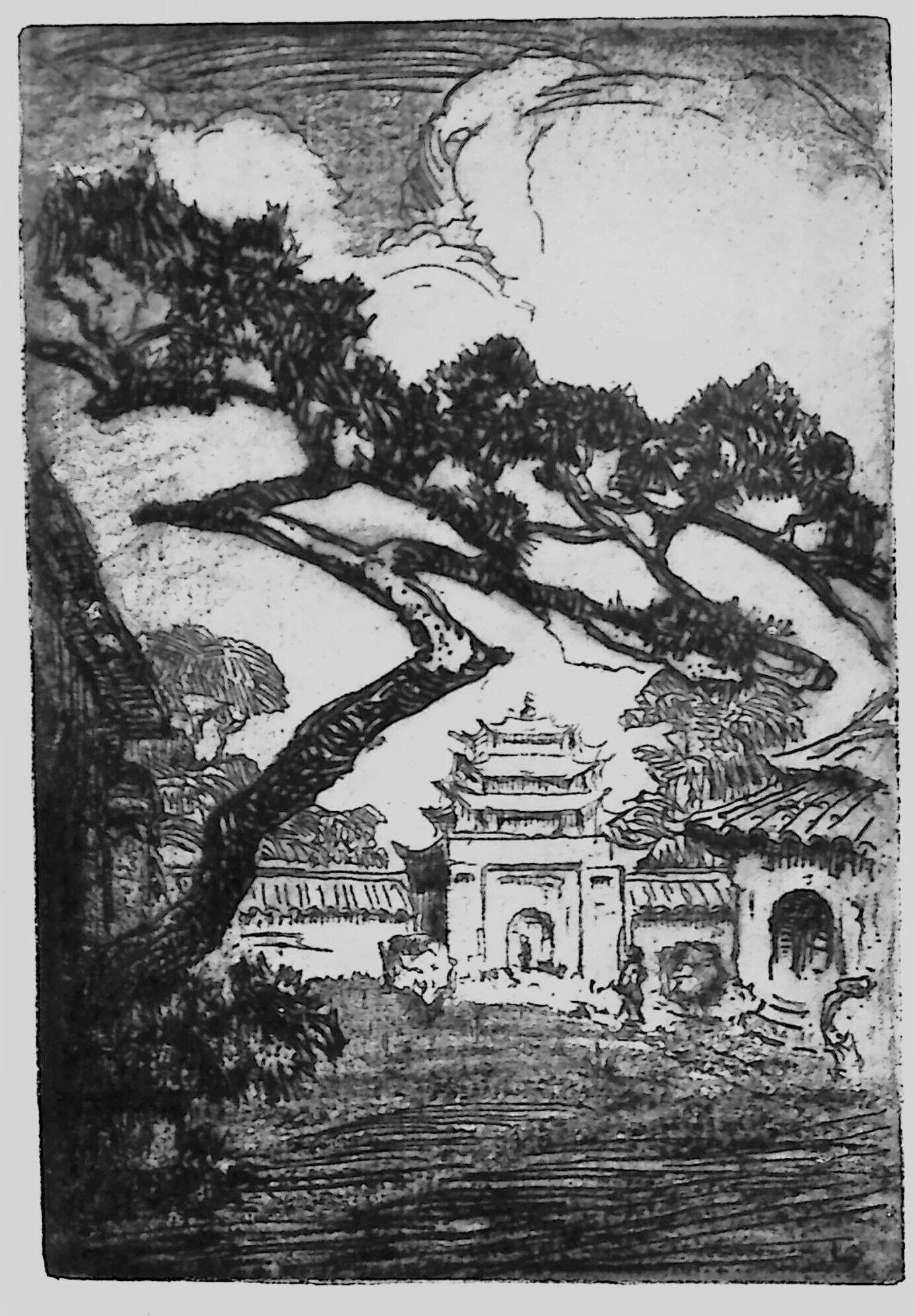

- Plate VI. The Emperor’s Palace in Legendary Hue | fp 40

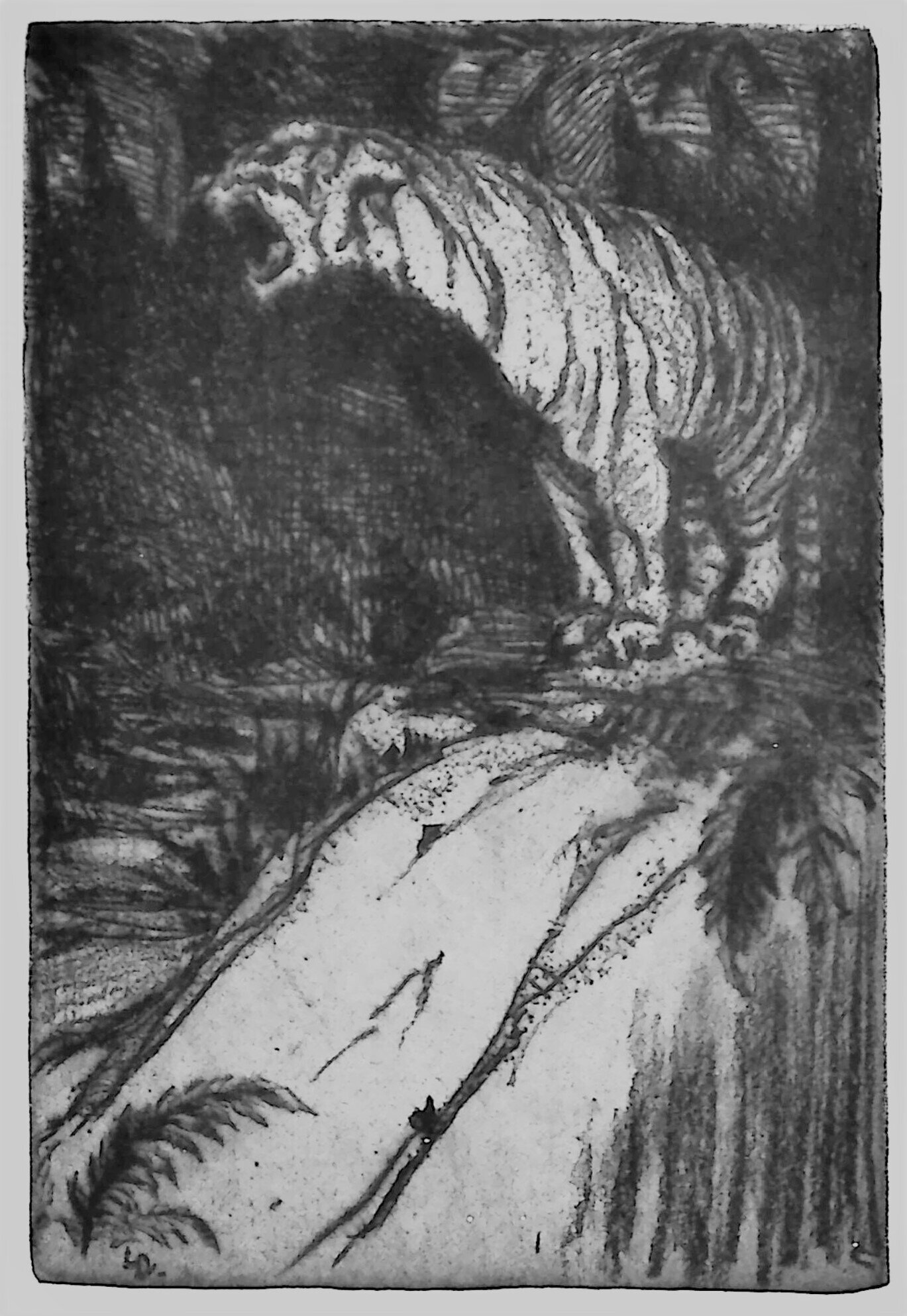

- Plate VII. The Dreaded Jungle Tiger — the Nameless One | fp 58

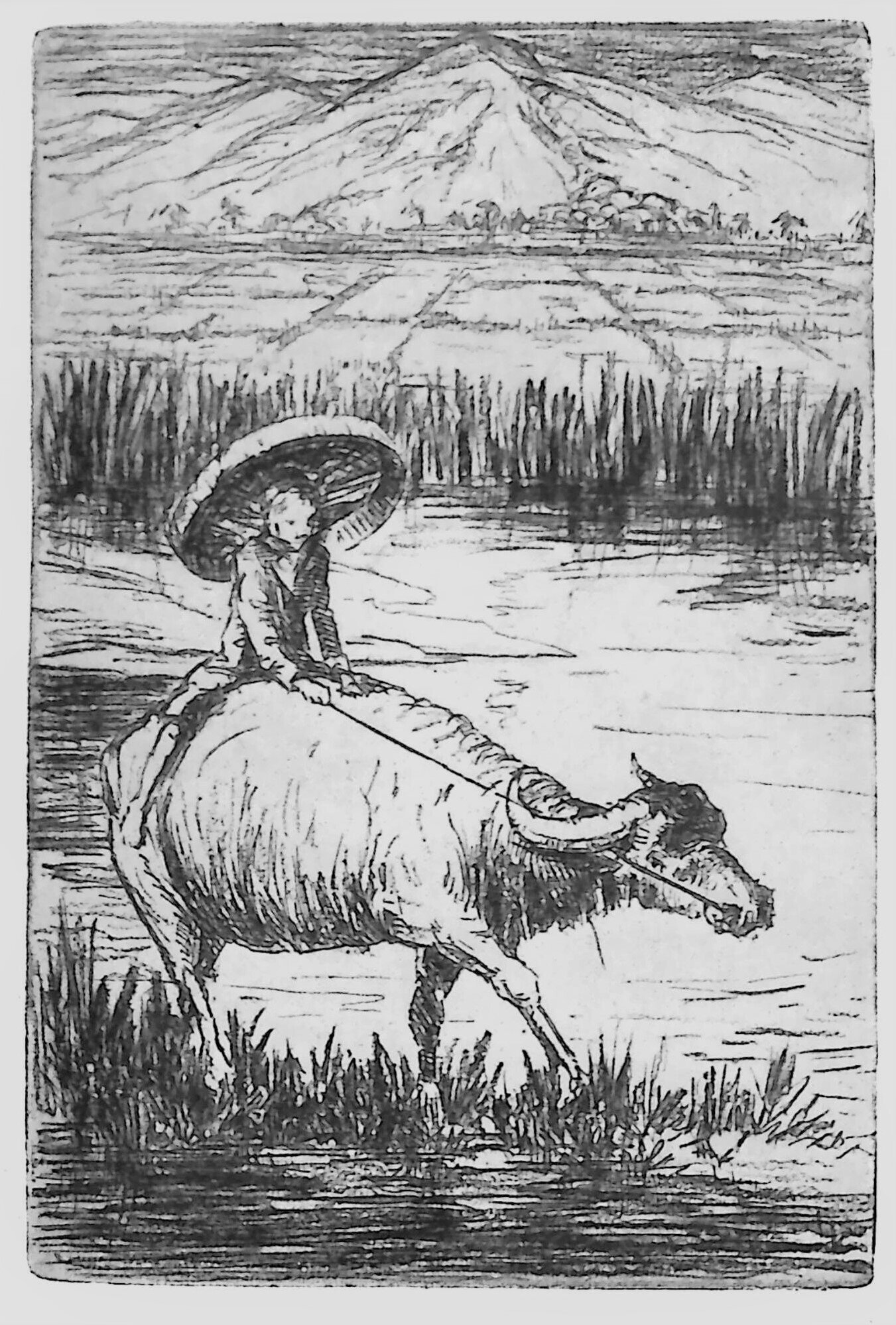

- Plate VIII. The Water-buffalo Ploughs and Harrows the Rice-fields | fp 72

- Plate IX. A Bac on a Road in Annam | fp 90

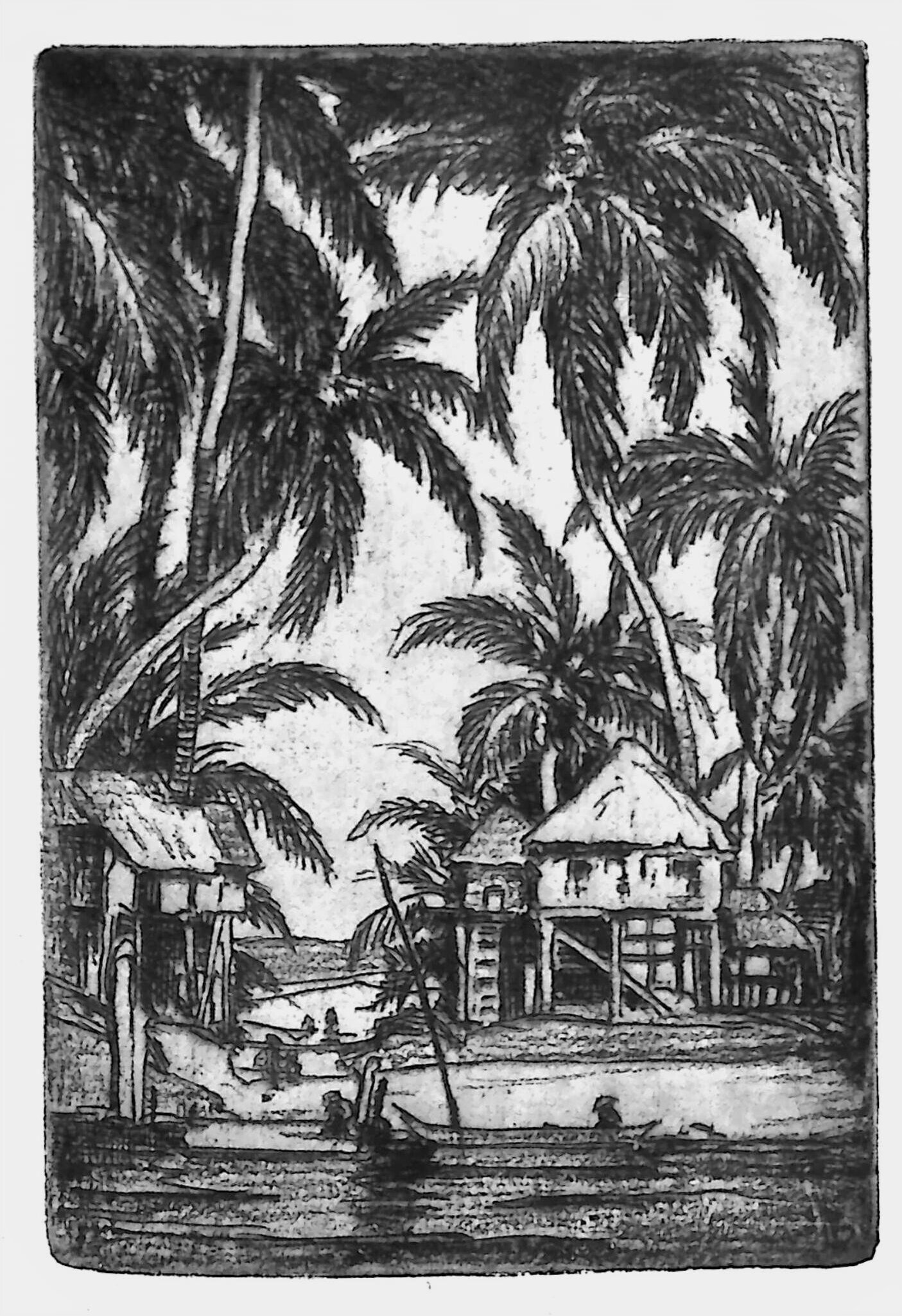

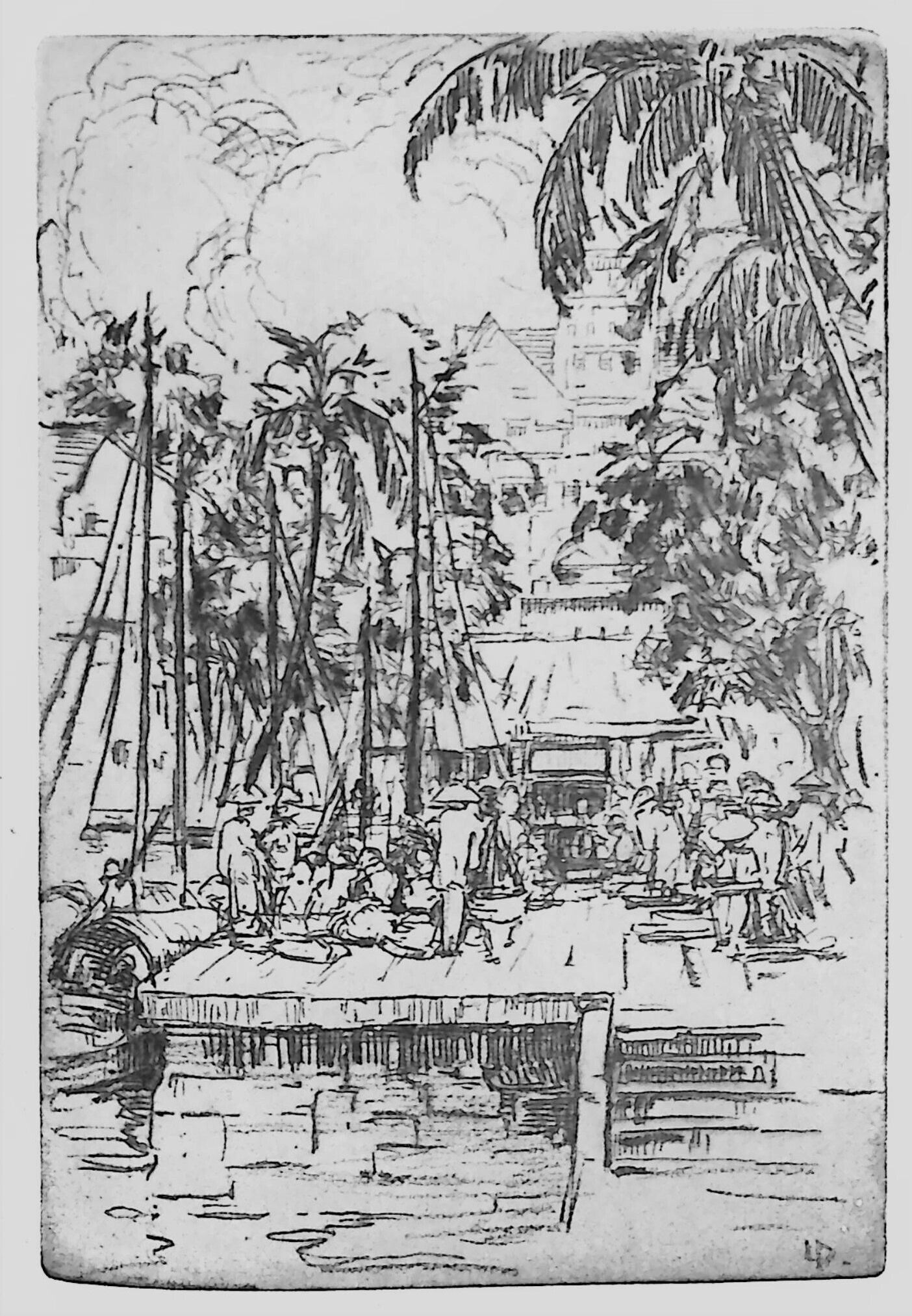

- Plate X. Saignon is Always en Fête | fp 108

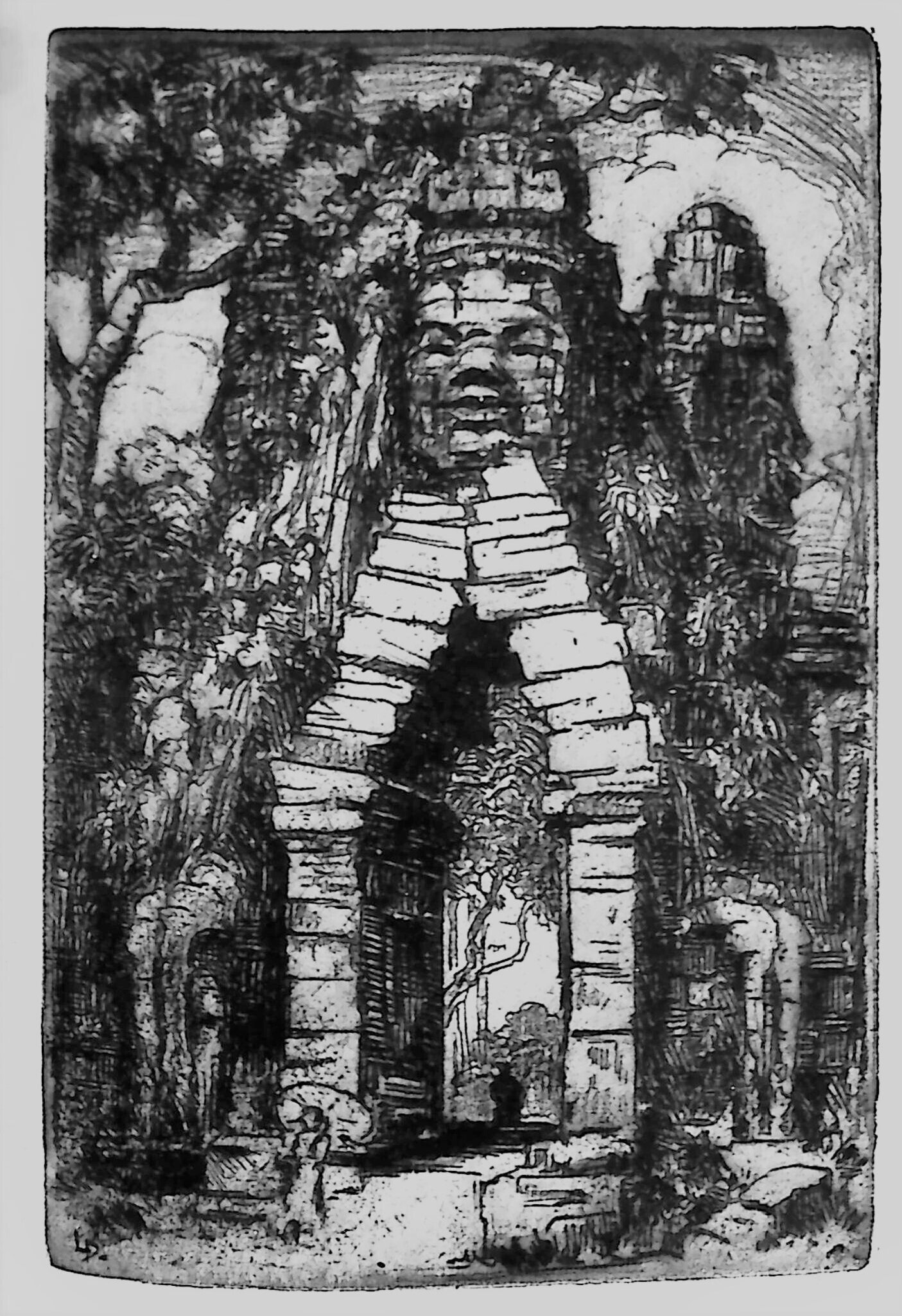

- Plate XI. Porte du Nord, Angkor | fp 124

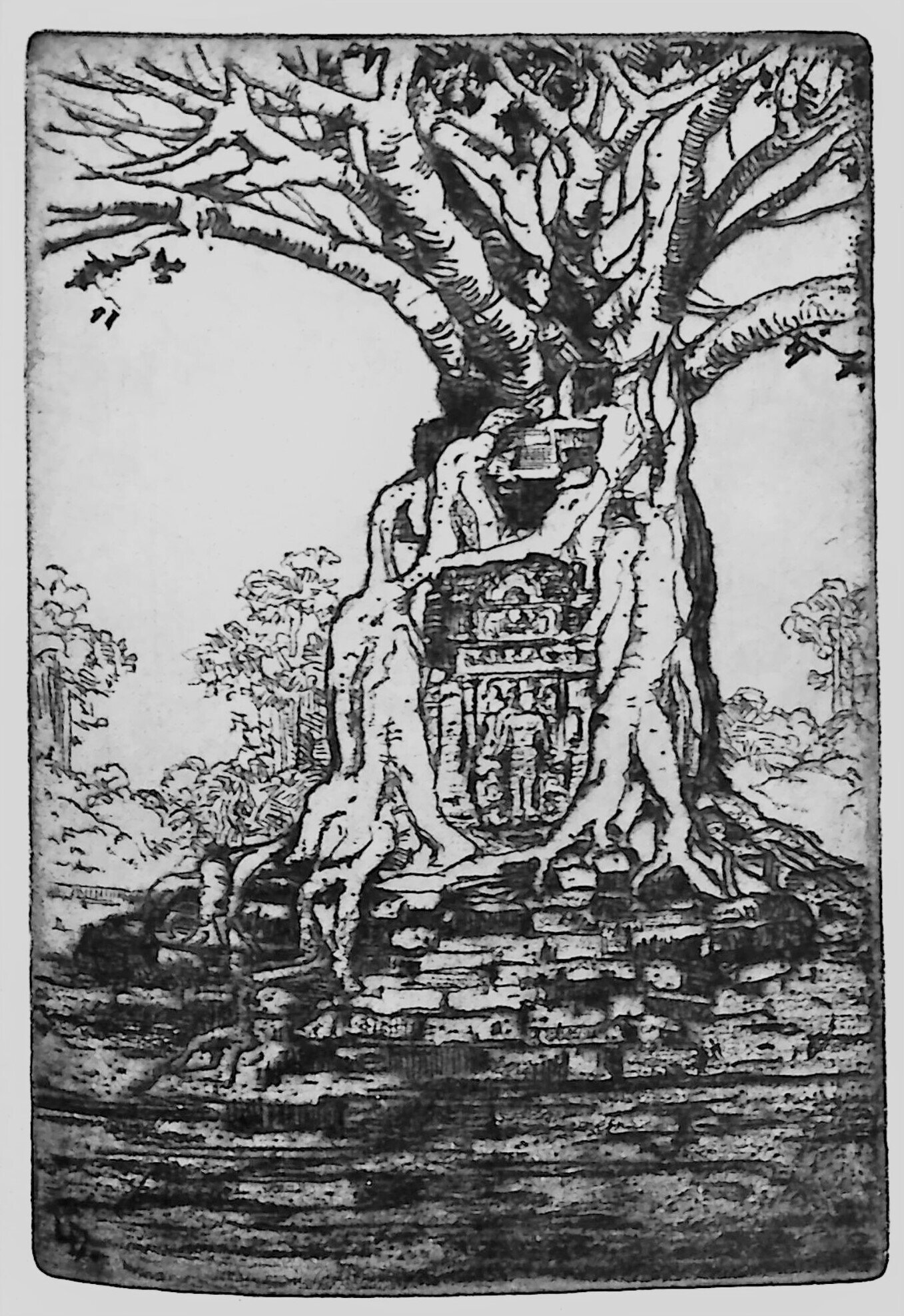

- Plate XII. The Temple of Neak Pean in the Clutches of a Giant Tree | fp 130

- Plate XIII. In the Palace of the King, Bangkok | fp 158

- Plate XIV. The Colossal Buddha of Ayuthia | fp 176

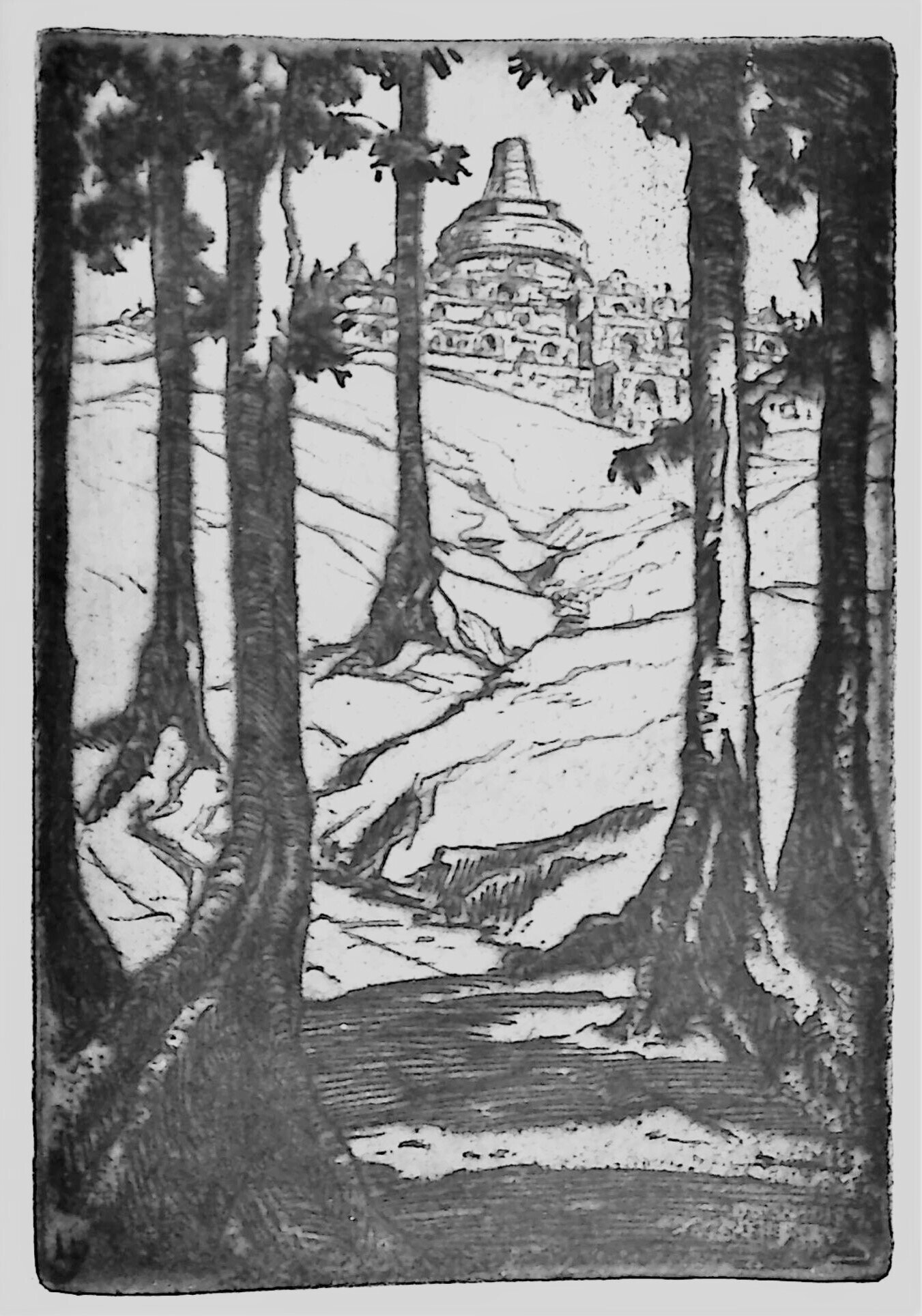

- Plate XV. The Ruins of Boro Budor, Java’s Noted Temple | fp 194

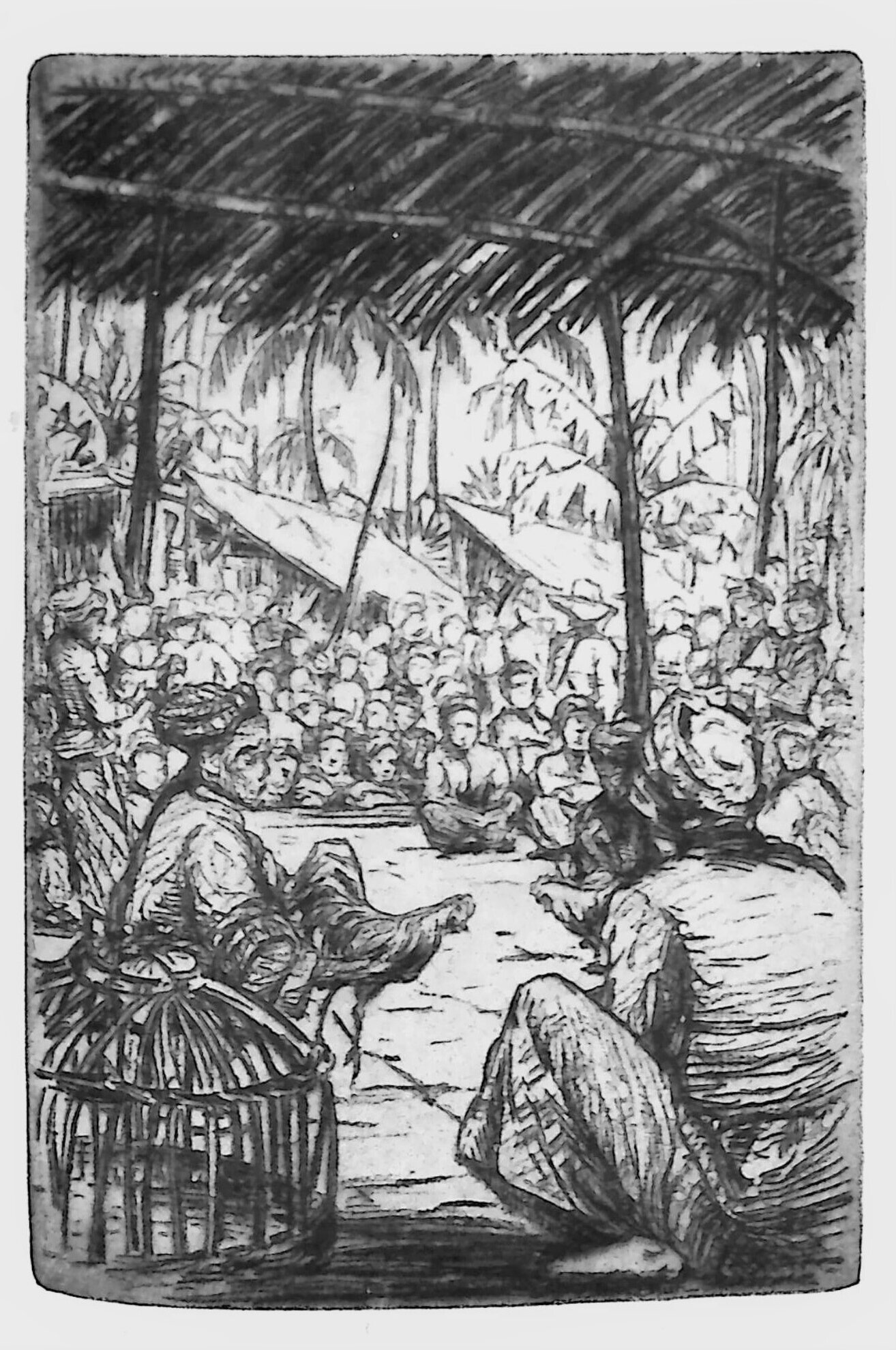

- Plate XVI. A Shadow-show at Djocja | fp 208

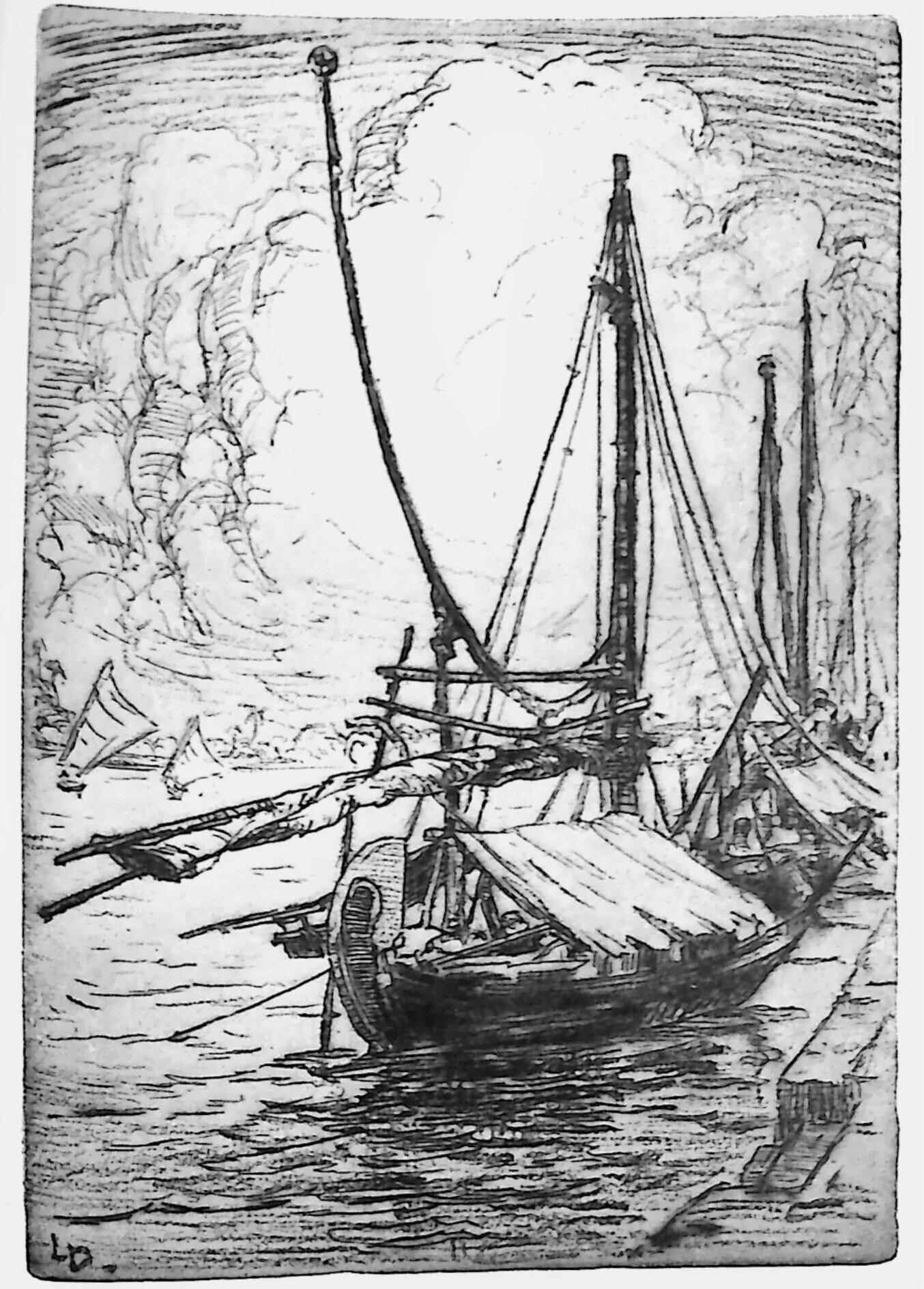

- Plate XVII. Javanese Boats are Strange-looking Craft | fp 226

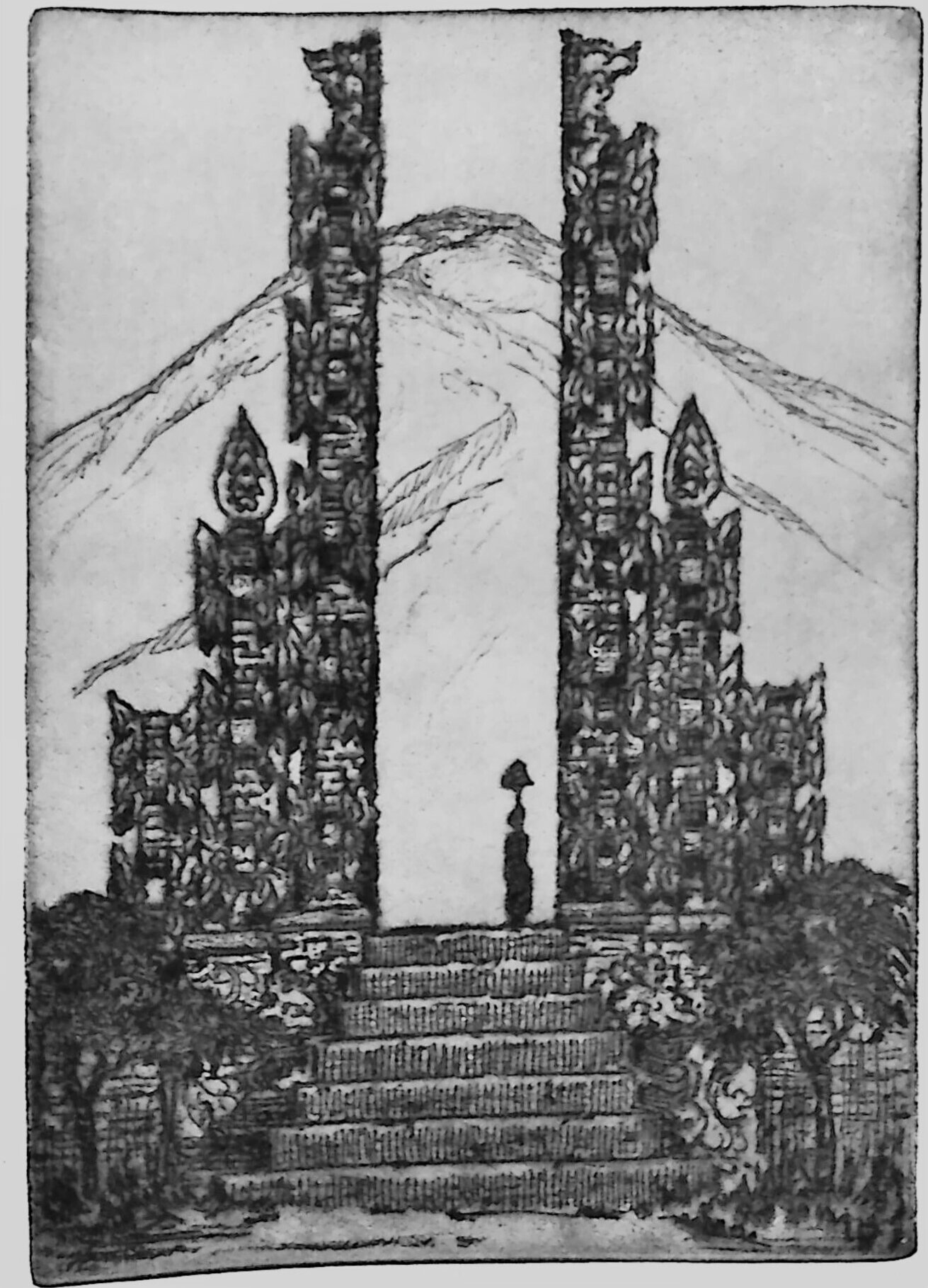

- Plate XVIII. Temple Gates in Bali | fp 242

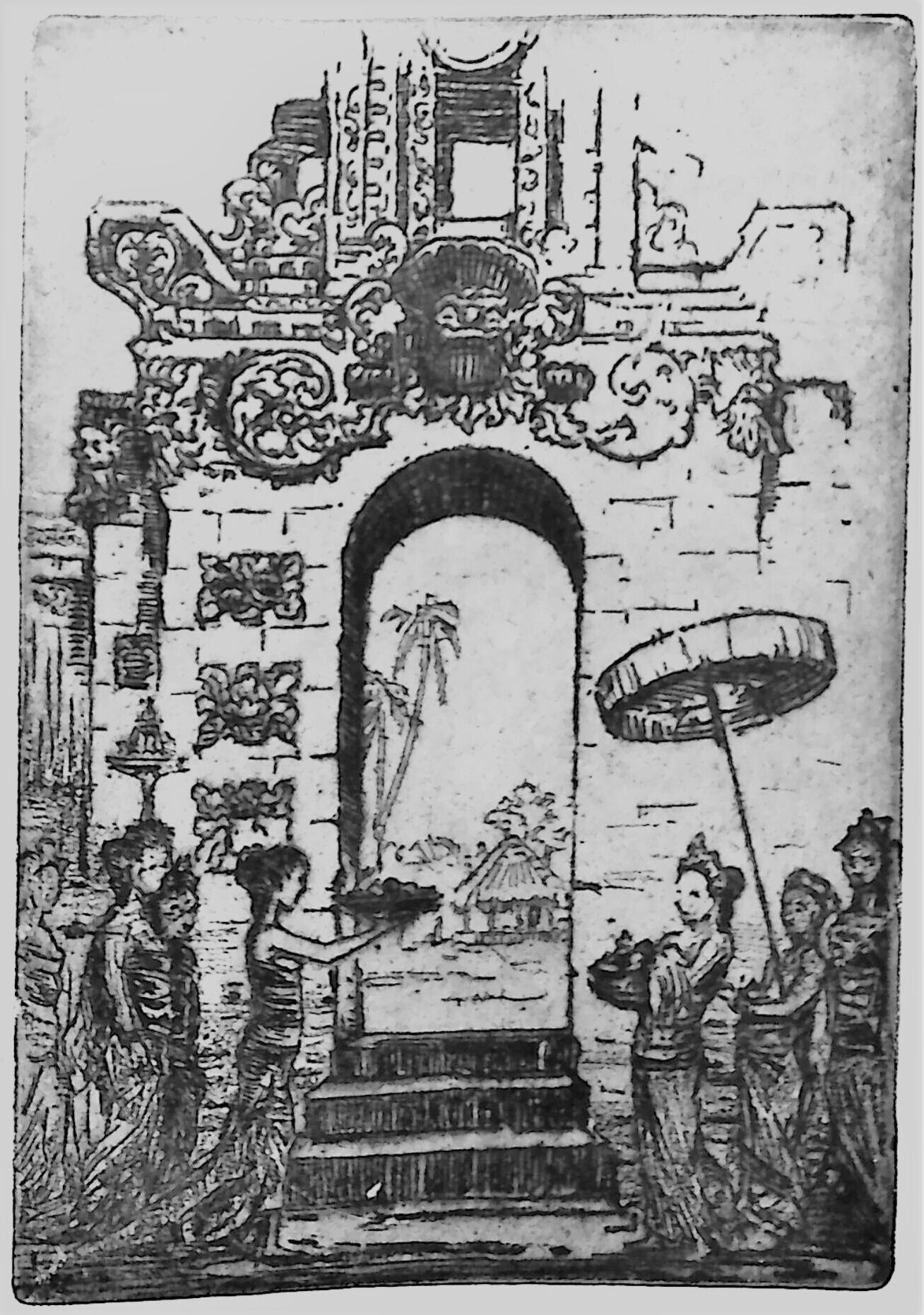

- Plate XIX. Beauty is Expressed in the Temple Offerings | fp 256

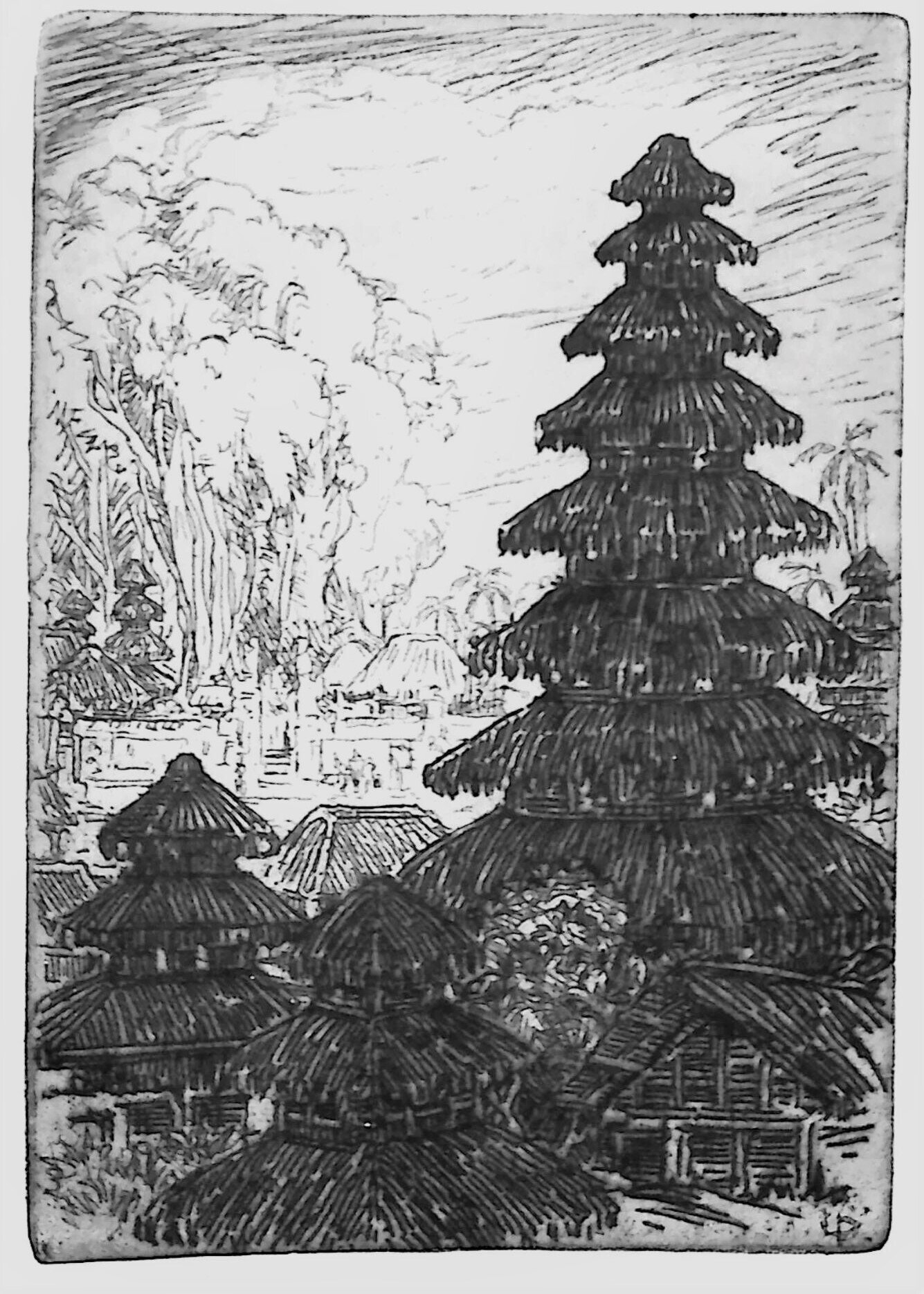

- Plate XX. Temple-leaves Like Those of the Greenwood Tree | fp 266

- Plate XXI. A Cock-fight in Bali | fp 276

The Pull of Angkor

The American artist was so taken by Angkor that she went back to Cambodia the following year, in 1927, this time on her own, and drew more views of the temples, drawings that were exhibited at the Paris Colonial Exposition in 1931. The Angkor Wat etchings are now held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Library of Congress. [see more here.]

After joining French archaeologists in several excavation and restoration projects — including Neak Pean temple and its giant tree, which had made such a lasting impression on Indologist Sylvain Lévi when he visited Angkor a few years earlier, in 1922), Lucille Douglass spoke on Angkor in many venues around America and Europe: at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the School of Oriental Studies (University of London), the Royal Asiatic Society and the India Society in London, Oxford University, the National Geographic Society.

In her communication to the India Society on 20 Oct. 1931 — titled “Angkor: A Royal Romance”, a phrase she often used alternatively with “Angkor: A Royal Passion”, she noted:

The jewel in the lotus is the little temple of Neak Pean, which is entirely possessed by a gigantic fig-tree. Set on a lotus-shaped island in the middle of a square pool, flanked by four corresponding pools, this tiny edifice is dedicated to Lokesvara. Some suppose that it is the entrance temple to the far greater Prah Khan about four miles away, but whatever its purpose it is wrapped in legend.

Jayavarman [VII] loved his subjects and consequently strove to ameliorate their sufferings. He built the great monastery-hospitals of Prah Khan and Ta Prohm and Banteai Kedei, and the records on the stele show how great numbers came for treatment, both of soul and body. Then he enclosed the capital city with a great wall pierced by five gates, surrounded by a moat, as if he was fearful of another revolt. This is the city of Angkor Thom. A great leader, a great king, he stamped his personality on the monuments which he left.

And she poignantly concluded:

Standing in the late afternoon sunlight on the temple-crowned Phnom Bakheng, a little to the south of the city, one looks across to where Angkor Vat floats like a fairy island in a sea of green, and wonders how long it will be before the jungle tide sweeps over the ruins and Angkor be lost to the world for ever.

[1] Stephen Goldfarb has also contributed to Lucille Sinclair Douglass: A Life of Art and Adventure, by Vicki Leigh Ingham, 2020, ISBN 978 – 0578666280 [foreword by Graham C. Boettcher, curator of Birmingham Museum of Art].

Tags: drawings, etchings, 1920s, women travelers, women artists, American travelers, Bali, Hong Kong, Saigon

About the Photographer

Lucille Sinclair Douglass

American artist Lucille Sinclair Douglass (1878, Tuskegee, Alabama –1935, Andover, Massachusetts) graduated in 1895 from the Alabama Conference Female College, where her mother taught art. In 1899, she moved to Birmingham, where she made a living as both an artist and an art teacher. In 1907 she and seven other female artists — Carrie Hill, Alice Rumph, Della Dryer, Hannah Elliott, Caroline Lovell, Carrie Montgomery, and Willie McLaughlin — formed the Birmingham Art Club.

From 1909 till 1913, she lived in Paris, studying painting and drawing with Lucien Simon, Emile-René Ménard (1862−1930) and Alexander Robinson, and held two exhibits of her paintings there in 1911. After returning to America, she joined the Methodist Missionary Society and, in 1920, was sent to Shanghai to oversee a workshop of Chinese female artists.

While in China, Lucille Douglass became close friends with two female writers whose books she would eventually illustrate, Florence Wheelock Ayscough and Helen Churchill Candee. With the latter, she visited from November 1926 till January 1927 Indochina, Siam, Java and Bali. It was also on this journey that Douglass first visited Angkor (Candee had been there before and had published the book Angkor the Magnificent in 1924).

Angkor was a revelation for the fifty-two-year old artist and, after illustrating Candee’s New Journeys In Old Asia with twenty-one etchings, she gave countless conferences on the capital city of the ancient Khmer Empire [see: “Angkor: A Royal Romance”.]

Back to New York, Lucille Douglass joined the “Floating University” from November 1928 until May 1929, teaching art on the ship President Wilson during a world cruise that included Southeast Asia.

After a long illness, Lucille Douglass died on September 26, 1935, in the home of a friend in Andover, Massachusetts. Her remains were cremated and, in the following year, flown to Angkor where they were spread around a “majestic mango tree.”

Read a complete biography by Stephen F. Goldfarb here.