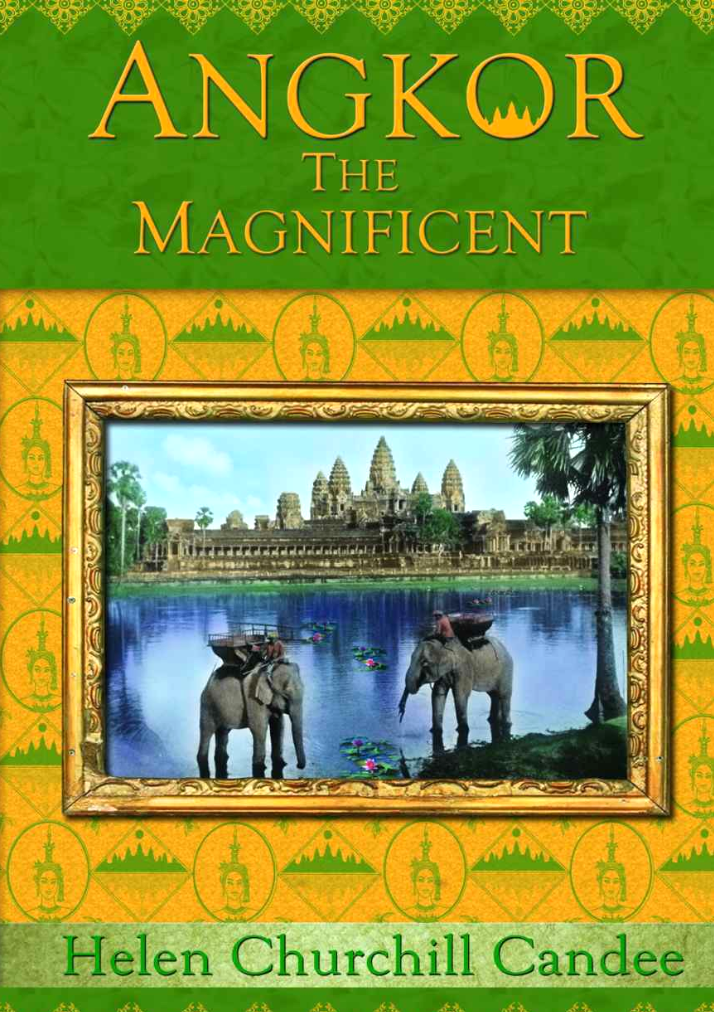

Angkor the Magnificent: Wonder City of Ancient Cambodia

by Helen Churchill Candee

The first published account of Angkor by an American woman, an intrepid traveler that had longed to see the Khmer temples "with a longing such as youth knows."

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, hardback

- Publisher

- eds. Randy Br Bigham and Kent Davis, DatAsia

- Edition

- hardover, 2008, and Kindle edition

- Published

- 2008

- Author

- Helen Churchill Candee

- Pages

- 250

- ISBN

- 978-1-934431-00-9

- Language

- English

We still don’t know why a New York socialite, ardent feminist, renowned interior designer and admirer of Chinese and Japanese art decided to undertake the “long, slow” journey from Phnom Penh to Angkor in 1922, coming from Hong Kong via Saigon and already a woman in her sixties. Did she happen to attend one of the numerous talks Isabella Stewart Gardner — also a New Yorker who had moved to Boston — gave when she came back from her own visit to Angkor in 1884?

Was it a simple yet powerful urge to fulfill a childhood dream, to see the “Wonder City of Cambodia” after a glimpse at some images of it, or reading Henri Mouhot’s account, which was well-known across the English-speaking world — she mentions him in her preamble, without naming him? Let’s quote from the opening pages which was to become even more popular in the USA than Mouhot’s Travels…:

When you have longed to go, with a longing such as youth knows, and with a poignant hopelessness such as maturity accepts, it is hard to realize that you are really off, that the journey to the land of delight is begun. The fantastic towers of Angkor had for months risen before my imagination, with their magnificent upward thrust above the tallest jungle. I could see their exotic silhouettes piling serrated points against a radiant mass of cumuli glorified by the low tropic sun as though the clouds copied them. […] The long, slow way is the overture to the Angkor drama, the quiet preparation of the mind for overpowering scenes. If Angkor Vat and its group were accessible to the tourist loafer at Saigon, if one could take a rickshaw or a gharri from the quay or the public gardens, and in a few minutes reach the ruins and hastily scramble over their bewildering terraces — one of the world’s greatest wonders might fail to thrill the souls of such hasty audience. With consummate art of progress the approach is prepared. After the heat and noise of the French city of Saigon, the deck of a river steamer is a refuge of cool repose.

Ladies fashion in Saigon

But before heading to the Khmer ruins, the author made a stop in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh Ville), and her expert eyes took in the state of French colonization, the culture clash, and the puzzling elegance of Vietnamese women, while attempting to find a far-fetched connection with Angkor:

An hour of lounging at the café reveals the surface of things in French Indochina. It shows the French as unhappy exiles, miserable in the work of colonizing. Every man and woman there lives but to return to France, and lives in a bitter imitation of Paris. All the requirements of a French town are found in this far Asian city. There are boulevards wide and umbrageous, their sidewalk cafes dressed with iron furniture, plants, awnings. And any drink found in Paris is found there. There is a huge municipal theatre and a cathedral; there is a palace for the governor general — veritably a palace, in modern French architectural grandeur. Other palaces are for each high official among the French. Commerce has also erected its palaces and the law has its Palace of Justice. The Rue Catinat has shops that would not disgrace Paris. Jewellers display the latest devices in precious gems, perfumers sell Houbigant and Coty novelties, booksellers have the newest novels and reviews, and — delightful touch to complete the illusion of a Paris street — the name of the great purveyor, Felix Potin, rises over a shop filled with his choice goodies and wines. A big department store dresses its many windows with everything needed for house or person. Through these streets of elegance and variety slip the slim little Annamite women all in black, humbly wondering at the ways of the people who have come to set them an example in deportment and in dress. Three or four stop before a corner window. It displays the bathing costume as worn at Deauville. Five wax manikins of pinkest flesh are posed in coquettish attitudes. Each wears an “Annette Kellermann” which that famous swimmer would be ashamed to wear. Above the waist, a couple of straps, below the waist but little more. And the smiles of the naked wax ladies are of such enticement as to dress them completely with indecency. Before this window stand gazing four young Annamite women, pale, serious, wearing their modest national dress, a close slip of black reaching from throat to foot, with sleeves to the wrist. What parallels are they drawing? I think of the ladies of the French colony swimming in these green and red scantinesses, and contrast them with the begrimed little slaves of the coal yard bathing after the twelve-hour labour in their long black gowns. The Annamites are beings I should like to know, really know, their animus, character, legends. For is not this one of the races intimately concerned with the Khmers of Angkor? Under the name of Champas they did heavy damage to the brilliant civilization I am approaching and which lies up this great river Mekong. […]

She is a lady of means for she is all in silk. The little head is poised above square shoulders on a line with the narrow hips. As she walks she thrusts forward her foot with a graceful freedom which outlines the length of the straight and supple leg. The effect is of drapery blown back by the wind and revealing an intoxicating symmetry. The black dress has true chic, yet is purely native. The long robe is fastened at the side, Chinese fashion, and is slit from hem to waist over the hip. Thus are revealed the straight trousers of whitest silk, below which show white silk stockings and black sandals. A white silk kerchief is tied over her head, and the close-sleeved arm upholds a parasol of heliotrope. She is all reserve. Aloofness is her guardian. She never looks at you — but how hungrily you wish she would. She walks alone as is the Annamite woman’s way. But no one speaks to her, nor breaks her reserve.

Phnom Penh

The arrival in the main city of Cambodia is the occasion for the author to depict a “gorgeous, shabby palace” — as an American, she had little interest for modern royalty -, and to pay a heartfelt tribute to George Groslier for his work both at the Museum and with the Ecole des arts cambodgiens:

At first blush Phnom Penh is a smaller Saigon, with fine French buildings facing a long quay, shaded avenues and public gardens. But scratch the surface and one finds more of the native. The French here seem less ennuye than in Saigon, and the natives less cowed. Cambodia announces itself, though it wear a French veil. This is the capital of Cambodia in that the Royal Palace is here where the king has residence. It was a clever move, to leave the king and his court while establishing a Protectorate, for it avoids a lot of dissension, perhaps of rebellion, among the natives. If they do not like the laws established by the “Protectors,” they have their king to whom to look. The king, however, is a lion with drawn claws. He lives in a gorgeous, shabby palace with little privacy, as it is ever on view to accredited visitors. The palace is almost barbaric in its treasures, as for instance a life-size statue of Buddha made of solid gold and ornamented with diamonds of prodigious size. Also it has a large hall furnished with a floor of pure silver tiles engraved. In another building the Sacred Sword is held inviolate. The palace has its department of the dance, quarters where live the many maidens who dance before the king to the music of a native orchestra. The monarch has also his herd of elephants on which to ride in ancient magnificence on occasions of state. But the court exists without vitality, a sort of shady circus which sketchily reproduces a dead grandeur for the amusement of those who buy tickets of admission. Alas and alas for kings, in these days of democracy! […]

Near the palace is the Khmer Museum. It is quite worthwhile, even to the most casual skimmer of surfaces. It is a bit of Angkor. It is an opening wedge to the European brain which lets in the new art of which Angkor is the highest expression. It is a preparation, but, after all, one should see it after the visit to Angkor to know what it really means. Here are collected wondrous bronzes and sculptured stones, jewellery and implements of war, dug from remains of the classic period of Khmer art, and one is puzzled and charmed with strange beauty. The courtyard is like a cloister with buildings all around the square, buildings open to light and air, in which young Cambodian students are being trained in the arts of long ago that native art may be kept vital. This museum, this school of art, are the life work of George Groslier. He elects to spend his life preserving the art of ancient Cambodia and in giving to the world an understanding and appreciation of the Khmer ruins. He is the apostle of Angkor. Shut in his museum, far from his loved France, he studies, works and writes that he may bring the world nearer the ancient work of a forgotten people. Does one wish to know profoundly the souls of the Khmers, those wild, luxurious conquerors, he should turn to the big French volumes of George Groslier, president of the museum at Phnom Penh.

For some reason the boat of the French company, the Messageries Fluviales, sails from Phnom Penh at night, just as does the boat from Saigon. After a French dinner with French wines and food, at a French hotel, one goes on board. One finds the same little cabins opening on the deck, and beds without sheets or covers.

The way to Angkor

As the skilled writer she was, Helen Candee staged her approach to Angkor, from a vividly described crossing of the Tonle Sap Lake to the first vision of Angkor Wat:

Then all at once the lake, Tonlé Sap. The unrippled spread of it is broken only by our big, white boat chugging along with scarce perceptible speed. The water gets low in January and should a high-spirited and impatient boat ram well into the mud, there’d be no help for it until the wet season came to float it off. They say that before the rain begins to fall the Grand Lac becomes only a grand mudflat. […] When a change came it was not land we met but a forest of spreading trees having water as their element instead of earth. Through their branches we saw the stars, below them the same bright sparks were sprinkled, and from the foliage came the music of birds that call at night. On and on through this endless enchantment. We no longer feared. Beauty was all there was in the world and it was ours. The stalwart boys who stood high at bow and stern propelling with long oars began to croon snatches of native songs with deep, sweet voices. […] We casually reached a shore. We had forgotten there was a shore or any element save water. […] In a moment we were being packed away in motor cars. Incredible! Motor cars at the end of three days’ and nights’ journey up a wild tropic river into the jungle! Faithful, ubiquitous Henry Ford awaited us.

I watched the roadside foliage for blazing green eyes. I watched the roadway for coiling cobras. Ten miles lie between the landing at Siem Reap and the Bungalow hotel at Angkor. I was on the alert to spy death before he saw me, all that long black distance. But had I satisfied a tiger, I myself was first feasted on beauty. The stars above the road were such as I had never seen, the birds; I heard were strangely sweet, the air which flowed around me was balm perfumed by a million flowers high on the forest trees. The Bungalow. The manager as affable as though it were not 2 a.m. gave us all big rooms with baths and netted beds. Sleep settled down over that section of Cambodia. But not until we saluted the Southern Cross low on the southern sky.

[…] Not one knew that before us stretched the great temple Angkor Vat. Next morning we rose, bathed, dressed, in a dreamy apathy of fatigue, thinking no further than toast and coffee. Then from each bedroom a figure stepped out upon the tiled verandas which serve as corridors and proceeded over the grass of the big square courts to the front. Raising our eyes, the great temple seized us. Sitting in majesty across a flooded space, it claimed us. It held out spirit arms and embraced us. The soft morning airs blowing from its grandeur baptized us into a new worship. The light glowing on its five distant towers illuminated our consciousness, our very souls. We stretched out our arms and stepped towards it in ecstatic forgetting of physical sense. We were not prepared to find it thus at hand. We had not been told it would greet us like the sun at early morning. We had planned to journey further to find it. We had even thought we would choose to see first the lesser beauties of the Angkor group, and save this famed marvel for the final joy. But we were thrown before its beauty unprepared, unshrived, unshorn.

“I sing the Bungalow”

With her eye for details and for the humble people behind the scene — the Cambodian guides, the mahouts, the hotel staff -, Helen Candee was to our knowledge the first and only visitor to give a full description of the Bungalow d’Angkor, later renamede Hotel des Temples, and a quite sardonic description of the early stages of “mass tourism” in Angkor:

I sing the Bungalow. To those who have not yet been to Angkor — all the world will go there soon — the magnificent ruins represent the whole interest. To those who are already there, the greatest building of the group is the Bungalow. No archeologist, no artist, even, is superior to its charms. After a few days’ stay therein you give it a wholehearted affection, though at first one may be unappreciative and take it for granted. It is low and affectionate in aspect. It sits on a pleasant green by the roadside and is shaded by mammoth trees which yet leave it open to moonlight and the stunning southern stars. A tiled veranda serves as corridor, each bedroom opens on a court like a tennis lawn, and each room has its own big bathroom with floods of water. Night’s rest becomes a joy. Nine o’clock is the welcomed time for beginning it. Yes, nine o’clock, for the tropic sun must be eluded by rising at six-thirty, breakfasting at seven and starting off before eight for the morning’s supernal delights among the ruins.

They know how to arrange for sleep at the Bungalow. Air is furnished by big windows thrown wide, at opposite ends of the room. Besides this the door is of the classic pattern made familiar by barrooms whereby feet and legs are the clue found by the observing outsider as to who lives behind. No, it is not immodest, not after the third or fourth day. Modesty seems to be an affair of climate when analyzed. After lights are out, all sorts of figures may be seen emerging from the doors of barroom pattern, and flitting across the grassy courts and down the blue-tiled veranda-ways. And they are not dressed in modesty’s garments long and thick. Heat affects the memory as it relates to clothing, and one forgets to put it on. And so one goes to bed with a view of lawn below the door and of stars above it, nor cares one whit.

Only, the boy who does the boots makes too early a clack on the tiles with his sandals at dawn. So I thought one night when his footsteps waked me before the light. Something unusual about it made me listen sharply. He did not move on. He stayed just the other side of that scant swing-door — a most trifling barrier against a night marauder. He continued to stay. The only sound was the occasional change of posture of the feet on the tiles. Dawn came with my imagination working torment. And dawn showed me the outline of spare, thin legs just the other side of the door. I lay still in the bed but shivered in the dawn breeze. The bed of the Bungalow is an ethereal Temple to Sleep, built of whitest linen on its flat mattress, and of gauzy net in its high upper structure. When one goes to bed the long, net curtains do not flow in a bridal-veil showering to the ground, but are tucked in hard and tight between mattress and spring, all around the square. Thus one is completely caged in a tight white box: thus is access to one’s highly valued body made difficult to such small night-prowlers as darting lizards and little snakes and the charming world of night-flyers — bats and beetles. You grow to think this the loveliest sort of couch. So it is, in the tropics. But when you are about to be attacked by a native who has long been standing outside your door, it becomes a trap. This book is not one of mad adventure, in it no life is lost nor greatly endangered. As the coming day gave me boldness, I struggled out of the lapped and tucked-in curtains, slipped across the room and peeped distantly through the crack of the door. A diminutive native horse turned away in astonishment and alarm, clacking over the tiles! How friendly then it all seemed. The great coldness between men and beasts that exists in other countries was not here. That tiny, lonely horse standing close to my bedroom door had come as to a friend. I even like lizards in my room now that I understand — though I pray I may never set my bare foot on one in turning out of bed.

The terrace outside the dining-room is another gem of the Bungalow. It is here that the most resourceful hotel host meets his guests, on arriving or at lesser times. He met each one to-day with smiles covering dilemmas. “Just received a telephone from the Messageries that twenty guests are arriving on the boat this evening.” “But the house is full!” protested all. “Yes, the house is full,” he agreed, shrugging and rubbing palms together in out-worn stage-business for hotelmen. But he smiled a cherry-red, friendly smile from a trusting heart. “We shall arrange.” And he did. He actually persuaded forty tired tourists to re-arrange their effects and alter their beds, to double up and squeeze up and make place for the coming twenty. The nicer proprieties took to the jungle — a healthful shock to them — in the process of doubling up, when by splitting rooms in two with curtains, brother and sister, mother and son, had temples of sleep in the same large cubicle. No one liked it much. The solace was a saintly feeling of self-sacrifice and brotherly love. This was most noticeable on the part of the Diva who consented to let her maid sleep with another maid and who overcrowded her own lofty apartment by letting her husband share a corner of it on a cot. The two reporters from Nice, however, spat venom at being cast into one chamber. The twenty were delayed — “Le bateau est dans la boue.” A tragic cherry-red smile beamed through the announcement. But at this time of year, late January, it always sticks in the mud at some part of the journey.

Therefore when they arrived at nine we were all fortified by an exceptionally good dinner of Parisian dainties, and warmer than ever was the saintly feeling of self-sacrifice, of brotherly love. The strangers came. They passed tired but spirited through the chairs and tables of the big, square terrace which smelled spicily of fresh coffee, cordials, expensive vintage smokes, and on to the grassy squares onto which gave the bedrooms. “Impossible!” “I cannot sleep two in a room!” “I must be alone.” “Unbearable!” “Some of the people already here can doubtless give up a room.” “The bureau in Saigon assured me there were plenty of rooms. So I’ll not submit to this.” The crowd came trooping back for dinner in this mood, making these remarks. We, the seniors, slunk off to bed knowing that no gratitude lay behind those hostile looks. But Monsieur of the Direction smiled and placated and fulfilled as ever, and the next morning the clouds had packed away. The morning had been spent clambering over the terraces of Prah Khan, that pitiful ruin which nearest approaches the great Vat in size. It is probable that had we known the feats of strength necessary for viewing this tumbled mass, we would have prepared for it by three months or more of physical training. Prah Khan is not revealed to the lazy nor yet to him of atrophied leg. It abounds in chambers of such green calm as haunts the caves of ocean, but these mystic retreats can only be visited by the athlete. And the company at the Bungalow were not athletes. After the exercise of the morning, luncheon was, during its first half, a determined effort to stop the clawings of an internal devil. Hunger is a most demanding passion, and a weakening fatigue is not a sweetener of tempers. And Cambodian waiters, alas, speak only their own agglutinate tongue, and become panicky if addressed in another. But the two journalists from Nice were the only ones who raged, flounced, snorted, and primitively misbehaved, before the feeding. After déjeuner, the terrace — and the contrast of peace after storm. What oil is to troubled waters, so is a glass of wine and a cup of coffee to troubled man. A dozen persons sat about with faces that smiled even in repose. Voices were low and sweet and the matter they expressed was like angels’ converse. And all because the passion of a vicious, hungry fatigue was satisfied at the Bungalow.

The heat descended and wrapped us round, until the rattan furniture seemed like hot cushions piled about the body; the blue-tiled floor was as a plate-warmer under the feet. The lizards of the wall neither clucked nor darted. Obviously the time of the siesta had arrived. Sleep nips two or even three hours out of the day at the Bungalow. The morning is for the serious ecstasy of studying the ruins. But late afternoon is for some innocuous pleasure. Sleep is the preparation for this delectable hour of strolling, of taking tea on the terrace, of reading or of studying the bands of natives that are ever slipping softly along the road with bare and silent feet. The fatigue of crawling over Prah Khan made a motor ride seem alluring. A motor ride in the jungle. Anomalous. Mowgli would shriek maledictions should he spy our machine. Presently the Ford — another shock — drove up and waited. The decorative young Bostonian who illuminated nature with her frocks got in beside the Artist, the Beguiling Guide in front. The engine buzzed, the driver was as stone. Of course. We had forgotten to tell him. “Néak Pean,” called the ready Bostonian splash of red, and the driver repeated it after his fashion which little resembled ours. Guides are faithful helps in the heavy morning tours. Resented, of course, for half the spell of the ruins flies away at the pointing of a finger, at the drone of a voice. The Cambodian guide cannot be said to drone, however, rather he blurts wildly a mispronounced syllable of what he understands as French. No English of course. He knows of only two languages, that of Cambodia and that of the country’s “Protector,” France. Some of these little dark men of Cambodia who serve at the Bungalow had their part in the Great War. France used even this far country to replenish her depleted man power. And thus these quiet people were plucked from their banana groves and rice fields and set in the trenches to “go over the top.” The “chamber maid” who makes the beds wears naught but a sarong or sampot on his sable person, and is tied to the soil. But he was a skilful aviator in France! Back to the sampot after all was done. After the wild flights over the terrible fields of blood and destruction, the return to the sheltered peace of the jungle village, the casting off of “horizon blue” and the freeing of the body. Here comes a query. Should one look upon an aviator of the Great War as a member of a savage tribe because he is now found in the jungle half naked, living in a bamboo hut, softly, quietly tropic in his inertia? After the European “bath of blood” how well he understands the bas-reliefs of the Vat. Long hours in contemplation of the battles chiselled there must now mean more than myths; they are vitalized and touch his own life with smashing conviction. We travelers — sometimes mere tourists — walk the long galleries guide-book in hand, trying to identify the tales of the Ramayana, the struggles between the Devas and the Asuras, conflicts of Khmers and Chams, and the muddled tempest of the battle of Hanuman’s ape-men. These are the strange plums we pluck from this unknown feast of art and archaeology, if we apply ourselves to the task. But he, my quiet bedroom boy, is our superior as he ponders, walking the marvellous ways of stone. About him is the mystery of a phantasmagoria, for these Brahmanic tales are mixed with his being, are a part of his aura. We, the invincible Europeans, we look with a puzzled superiority on these fairy tales. But he, the Cambodian soldier returned from the Great War, draws deadly parallels of the conflicts. The native who drives for us Henry Ford’s great gift to all the peoples of the earth, was dressed in a hot linen suit, heavy leather boots and hat which would produce sweat on the brow in Iceland. European influence is written all over him. He has also a pride that brooks no orders, and an overbearing insolence to the drivers of bullock carts on the road. But he was dull and indifferent. Perhaps he hated us that hot afternoon.

The hour was late. The sun was low enough for the tree-shadows to cover all the way. The greatest heat was gone and the soft air caressed as we flew through the scented jungle and passed under the gate of Angkor Thom. From the flowered roadside came a piercing note continued on one key longer than is good for the eardrum. A cicada. One would have said it was the disconcerting bore of the steam whistle which attaches to the peanut stand of New York’s Greek vendors. No poetry blooms around this sort of cicada. Past the Bayon with its Brahmanic towers, past the Terraces of Honour. the Phimean-Akas, out the farther gate of the city of a million souls, and around the turn of the drive which skirts the temple of Prah Khan, whose ground plan almost equals that of the Vat in size. All these things are friends to those who know them, but even friends are passed by when other matters call. And we were bent on seeing Néak Pean, the tiny temple in the clutch of one giant wild-fig tree [later struck down by lightning, ADB]. “I like its name,” said the splash of soft orange-red from Boston. “The guides never take us there, it has an aristocratic aloofness which makes it choice,” explained the Beguiler. Spoiled children of civilization. The motor stopped. We might have stopped anywhere along the way and found as distinctive a place. The wondrous trees grew sky-high above us, dropping perfume, the birds called among them, but we were buried in the jungle with no sign of the glory of man. A little path perhaps. Yes, the sulky gentleman in linen suit and peaked cap was indicating one, a mere thread on the carpet of the forest. We followed it alone, leaving the white-suited man lighting a cigarette, with a sneer, an unmistakable sneer, on his brown face. Which sneer was certainly possible to read without the help of Pali, Sanskrit, or modern Cambodian. He did not approve of our Anglo-Saxon ways.

Tevadas, Apsaras and real Dancers

Like Harriett Ponder a decade later, the author had the privilege to witness a live dance performance at Angkor Wat — on the western causeway and terrace -, right after spending hours marveling at the carved female figures on the reliefs of the temple:

The famous smile on the face of Leonardo’s “Gioconda” is not more enigmatic than that with which these Khmer ladies greet the visitor. They stand in groups with arms affectionately interlaced, or singly, upholding a flower or an end of the strangely draped sampot. Gauze and silk clothe them, and the sun has taught them to be half naked yet unashamed. Jewels adorn them and headdresses create wonder. These friendly, pleasant ladies are placed against a gracious background carved as though by a goldsmith, so patient and so talented are its infinitesimal details. They stand and look at one across the chasm which ever separates beings of differing race. It is not the years that part us, it is the opposing point of view which holds apart the West and East to the heavy loss of both.

In another part of the Vat one comes on the dancing figures, mad, joyous beings. You know these are fable. The girls — Tevadas you may call them — are human, but these lightsome dancers are too happy to bother about hearts or souls with all their appanage of serious thoughts. Their mission is to enliven, to divert. Religious dancers they are called, but one questions why. In dress and ornament they are not unlike the Tevadas, the enigmatic ladies, but in attitude they are fascinatingly acrobatic. No more exquisite entourage was ever made than the frame for these figures, a flowered scroll which gracefully widens to accommodate the active knees, narrows for the slender waist, swells again for the head, and forms altogether a vase-like outline. The fabled Apsaras are kin to this figure, ancestors perhaps. One feels that the court of Angkor must have abounded in dancers like the one dancing within her frame, but Apsaras are of the gods. They are the maddest, merriest beings on the Hindu Olympus. They are always in battalions, always high in air above the actors in a scene played by gods or demi-gods. No human could be so abandoned to joy as these heavenly acrobats, the sales of whose feet are lifted to the sun, fairly spurning both earth and heaven can they but dance between. Untellable are all the varieties of pure decoration, but still another is always taken away in the mind’s depository of photographic films. It is the delicious parade of little men who perform ecstatic antics on the backs of the strange mounts they are riding. A frieze of them runs above the groups of winsome girls, just over the balustered windows of the courtyard. Each mount, a horse, an elephant, a rhinoceros, is rampant, each rider is as joyously acrobatic as the lady of the circus on her trained stallion. And all is done, not as an exhibition but because some inward spirit demands a wildly reckless expression.

[…] The Cruciform Terrace is already filled with a quiet audience vibrating expectancy, yet room is rapidly made in the choicest place that visitors may have the best. The right arm of the cross contains the orchestra of fine-singing strings and time-beating tom-toms; the left arm is completely filled with women standing and crowding to shield the dancers who have been dressed and ready for hours. The centre is cleared, and the brown torch-bearers are seated in an arc of lights as an entourage. Above, scarce seen, like a shadowy cloud in the heavens, the dominating protection of the great Khmer temple. A hush, the sound of tinkling bells and strings, more insistent beatings of the drums, then an arresting stir among the crowd of women and a distant glistening of jewel-dressed heads moving with decision. Eight dancers advance through the retiring crowd of women to the centre of the terrace, four princes, four princesses. They come with high rhythmic tread, a dramatic pause between each step, a pose almost, as each lifted foot throws the weight. And the magic feet are bare and rest flexile on the pavement, strong to keep faith with balance. Heads are high and steady, arms and body undulate and sparkling eyes tell of nerves alert, though the faces are the serious moon-like faces of children.

The première princess is gorgeous in silks and jewels and high, pointed headdress. A tassel woven with fragrant jasmine flowers adds piquancy as it falls beside the rounded cheek. She is buoyant with knowledge of her beauty and skill. She leads her line to the front. She plants firmly an able foot tinkling with bangles; she poises and sways her supple body and waving arms, she sets firmly the head and poses as the Tevadas danced before the Khmer kings ten centuries ago. She is the dancer of the bas-reliefs made flesh, the carving made alive, repeating the incredible postures with the plasticity of life. In her face rest sobriety and aloofness as she looks far out into the dark as to some high, impalpable audience for whom she dances. Equally beautiful with her lovely head are her marvellous hands. Rounded and firm are the arms like waving branches or swaying like Naga himself; but the hands of the Cambodian dancer are like no others. The fingers bend backward like long white petals of the lotus separated by the evening breeze and turn in strange and eloquent grace. Raised high, posed low, or undulating on the level of the shoulder, hands and arms ever sway as the wind of dawn sways the orchids hanging in the trees of the jungle. No less elegant is the leader of the line of princes. Only in dress does he differ from the princess, but in the progress of the drama his role is apparent. With play and interplay the two lines of dancers hold the happy attention of the wide-eyed torchbearers, of the crowd of men around the musicians, and the beaming women.

[…] The reunited lovers end the dance by leading in a joyful series the swaying lines of slender maids. It is incomparably beautiful. And the setting for so simple a drama before so simple a people is of a grandeur indescribable. The dance ends. The weird orchestra stops its tinklings, the fifty brown torchères fly down the long way to brighten the path for the foreigners who are the first to troop away. In the sweet-scented dark the causeway is animate with the village audience making no sound louder than the sibilant whisper of bare feet slipping over the smooth stone paving. Under the heavy trees by the roadside the bullock carts wait to carry home the humble dancers. And over all brood the terrifying, inspiring towers of the Sanctuary.

A thorough and insightful description of Angkor Thom

Follows a detailed account of her passing through the Khmer temples, the Bayon, Phimeanakas, Preah Khan, smaller temples such as Preah Pithu. Perceptive, detailed without becoming overwhelming, Helen Candee’s notations are still pleasurable to read. She even mentions the famous account of Zhou Daguan in 1295. We do not know whether George Groslier accompanied her in this inspired visit to the temples, but his insights are everywhere in her remarks, as Groslier’s artistic perceptiveness spoke to her more decisively than dry archaeological reports. The closing lines are a diplomatic acknowledgment of the role of France in preserving Angkor:

Romance is not hurt by noting that twice during the centuries of oblivion missionaries brought word of Angkor, though the word was unheeded. In 1604 a Portuguese priest, Quiroga de San Antonio [the author here confuses Quiroga with Fra Antonio da Madalena, who passed his first hand account to chronicler Diogo do Couto, ADB], told of two hunters who perceived magnificent ruins in the jungle about 1570. And in 1672 a French missionary, Père Chévreuil, spoke of the place, calling it Onco.

After that, silence until a broken line of French explorers drifted up the Mekong and the Tonlé Sap. The line began in 1858 with Henri Mouhot and was continued by Commandant de Lagrée, Francis Garnier and Delaporte. The latter was the first to make, in 1871, an equipped expedition with large personnel. The first complete plans of the ruins were made by the Lajonquière in 1900.

In 1898 was formed by the French the institution called l’Ecole de l’Éxtrème Orient [sic], a body which was keen to make scientific explorations of the Khmer ruins and to take means to preserve them. But Siam was in control of the district and only by her permission could the French enter Angkor. Persuasion was used — of a kind known to international politics, and by means of a clause in a Franco-Siamese treaty of 1907, three provinces were returned to Cambodia — and Cambodia was already within the French Protectorate. Alors! the future of Angkor and the Khmer ruins was assured, being in the hands of France.

Tags: women travelers, 1920s, Angkor Wat, Angkor Thom, Saigon, women, Khmer arts, dance, apsara, devatas, EFEO

About the Author

Helen Churchill Candee

Helen Churchill Candee (née Helen Churchill Hungerford 5 Oct 1858, New York City – 23 Aug 1949, York Harbor, Maine) was an American author, journalist, interior designer, active feminist and geographer whose book about Angkor, Angkor The Magnificent (1924), is regarded as the first major English-language study of the ancient Khmer temples.

A determined and independent traveler, Helen Candee escaped death during the sinking of the HMS Titanic in 1912 — a part of her account of the disaster is said to have inspired the world-famous “sunset scene” in the eponymous movie. As a nurse with the Italian Red Cross during WWI, she attended wounded soldiers and reporters, among them Ernest Hemingway. In 1924, as she was living in Beijing, she was caught into the Chinese Civil War and sent dispatches from the front lines — on the side of the Nationalists — to the New York Times.

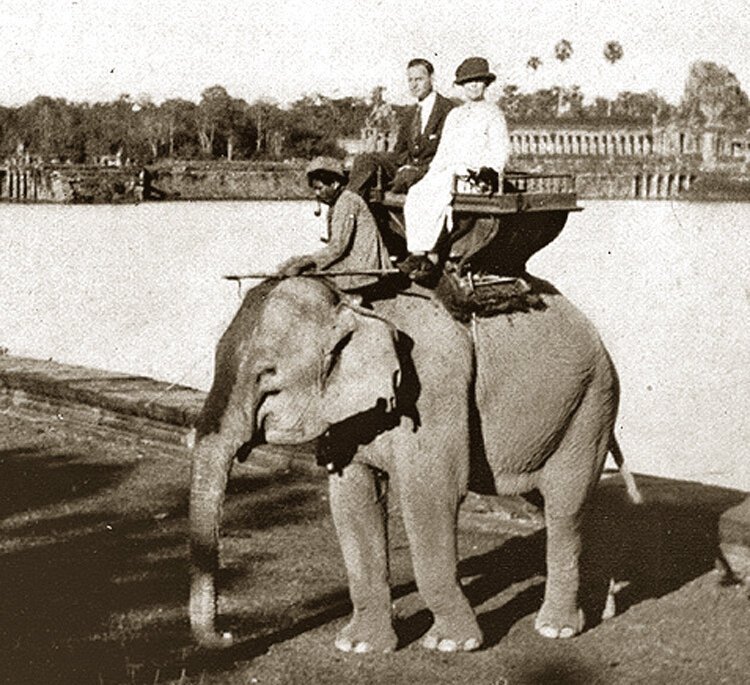

She could have claimed to be a scion of USA “Founding Fathers’, as she descended from Elder William Brewster, who came to Plymouth on the Mayflower in 1620. Educated in private schools in New Haven and Norwalk, Connecticut, she was a strong-willed young woman, and did not shy away from obtaining a decree of separation from her husband, Edward W. Candee, who had abused her and their two children, Edith and Harold. “Harry” was with her when she visited Angkor in 1922 - she nicknamed her The Beguiling Guide or The Beguiler in her account -, but died of pneumonia in 1925, 39 years of age, one year after the publication of her acclaimed book.

Back to the divorce, Linda D. Wilson has explained in The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture why Helen Churchill’s first novel was based in Okhlahoma: “A life filled with entertaining and travel masked a troubled marriage to an alcoholic, abusive husband. After an unsuccessful attempt for a divorce in New York in July 1895, Helen and her two children traveled to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory, where divorce seekers could obtain a decree after establishing a ninety-day residency. F. B. Lillie, the first registered territorial pharmacist, and his wife opened their Guthrie home to Helen Candee. While staying in Guthrie, Candee gathered ideas for her novel, An Oklahoma Romance (1901). Probably the first novel written about Oklahoma Territory, it tells the story of a land claim dispute, after the Land Run of 1889, between a young doctor and a politically established man. Several Guthrie citizens recognized themselves as characters in her novel. Candee also published articles in national magazines about the social and economic conditions in Oklahoma Territory as well as an article about the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Opening in 1901. Hiring Guthrie lawyer Henry Asp, Candee obtained her divorce in Judge Frank Dale’s court in 1896. She returned to New York City, and she continued to write.”

Already renowned for her books and press articles on women’s rights and decorative arts, Helen Candee traveled to the Far East after the war and wrote a major description of Angkorian ruins. While this book was publicly lauded by the French government and the King of Cambodia, she was invited to read parts of it to King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace. In 1927, she followed up with another book, New Journeys in Old Asia. One chapter of this work is titled “Leaving Angkor”.

According to biographer Randy Bryan Bigham, “New Journeys in Old Asia, a thorough treatment of her Oriental dreamland, touching on Bali, Siam, Java, Bangkok, Singapore and Thailand, was the culmination of three years of traveling, accompanied by her friend, artist Lucille Douglass, who provided the book’s etchings. In the course of that trip King Sisowath Monivong of Cambodia and the resident French government honored Helen for her earlier work, Angkor the Magnificent.”

As for the Titanic tragedy, Helen Churchill Candee wrote in 1912 a piece, “Sealed Orders”, in which she noted: “The rescue ship plucked Helen and 711 other survivors from the sea. For every life on board, three braver ones had surrendered theirs in God-like selflessness. The icepacks lay for miles, dazzling in the sun, peaks rising proudly here and there. Seals, black and shiny, showed in the waters, gulls flew and cried — active white against silent white. Superb, thrilling, dominant, the ice held the region with nature’s strength. The power greater than man’s had prevailed, the crushing force against which there is no defense, no pity, no sparing. It was the power that is of God, which is the divinity of noble men.”

In-between her two successful books on Southeast Asia, she was among the nine founding members of the Society of Woman Geographers in 1925, later becoming a frequent lecturer on the Far East, and keeping publishing articles for the National Geographic until the late 1930s, when she was in her eighties. She remained active in the world of interior decoration, becoming the editor for Arts & Decoration in Paris in 1920 – 1, then staying at its editorial board.

In Helen Candee’s biography by Randy Bryan Bigham for The Encyclopedia Titanica, we can see a photo of the author leading the 1913 suffrage parade “Votes for Women” on horseback in Washington, D.C.

Publications

- Susan Truslow, 1900 or 1901.

- How Women May Earn a Living, Macmillan & Co, 1900.

- An Oklahoma Romance, The Century, 1901. [her only fiction book.]

- Decorative Styles and Periods in the Home, Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1906.

- The Tapestry Book, Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1912.

- “Sealed Orders”, Collier’s Weekly, 4 May 1912 (Vol. 49, no. 7); repub. in Angkor the Magnificent 2008 | repub. Sealed Orders: A Lost Short Story of the Titanic by a Survivor, Spitfire Publishers, 2018.

- Jacobean Furniture, Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1916.

- Angkor the Magnificent: Wonder City of Ancient Cambodia, Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1924; repub. Angkor the Magnificent, eds. Randy Bryan Bigham, Kent Davis, DatASIA, 2008. ISBN 978−1−934431−00−9.

- New Journeys in Old Asia: Indo-China, Siam, Java, Bali, Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1927.

- Weaves and Draperies: Classic and Modern, Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1930.