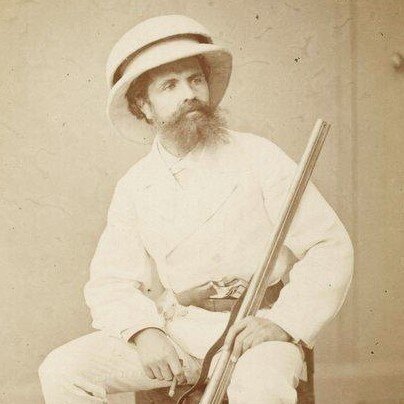

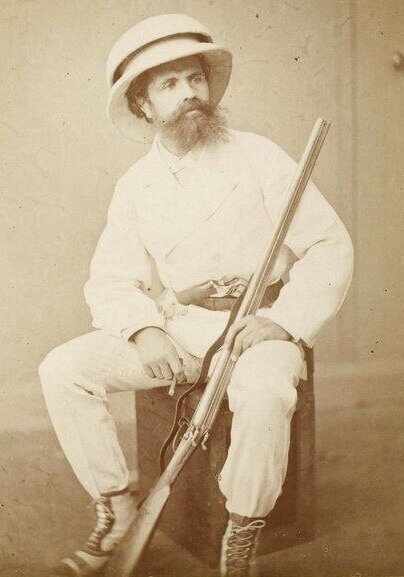

During the nine days he stayed in Phnom Penh (8−17 February 1885), French commercial envoy Xavier Brau de Saint-Pol Lias marveled at the city, attempted to no avail to get an audience from King Norodom (“but I met the whole Royal Family, including the second King, the King’s brother”), observed the daily life of “a mixing pot of 18 races”, went to the outskirts, tried to forget his fear of the Cambodian insurgents led by Sivutha who had reached near the city, and took photographs.

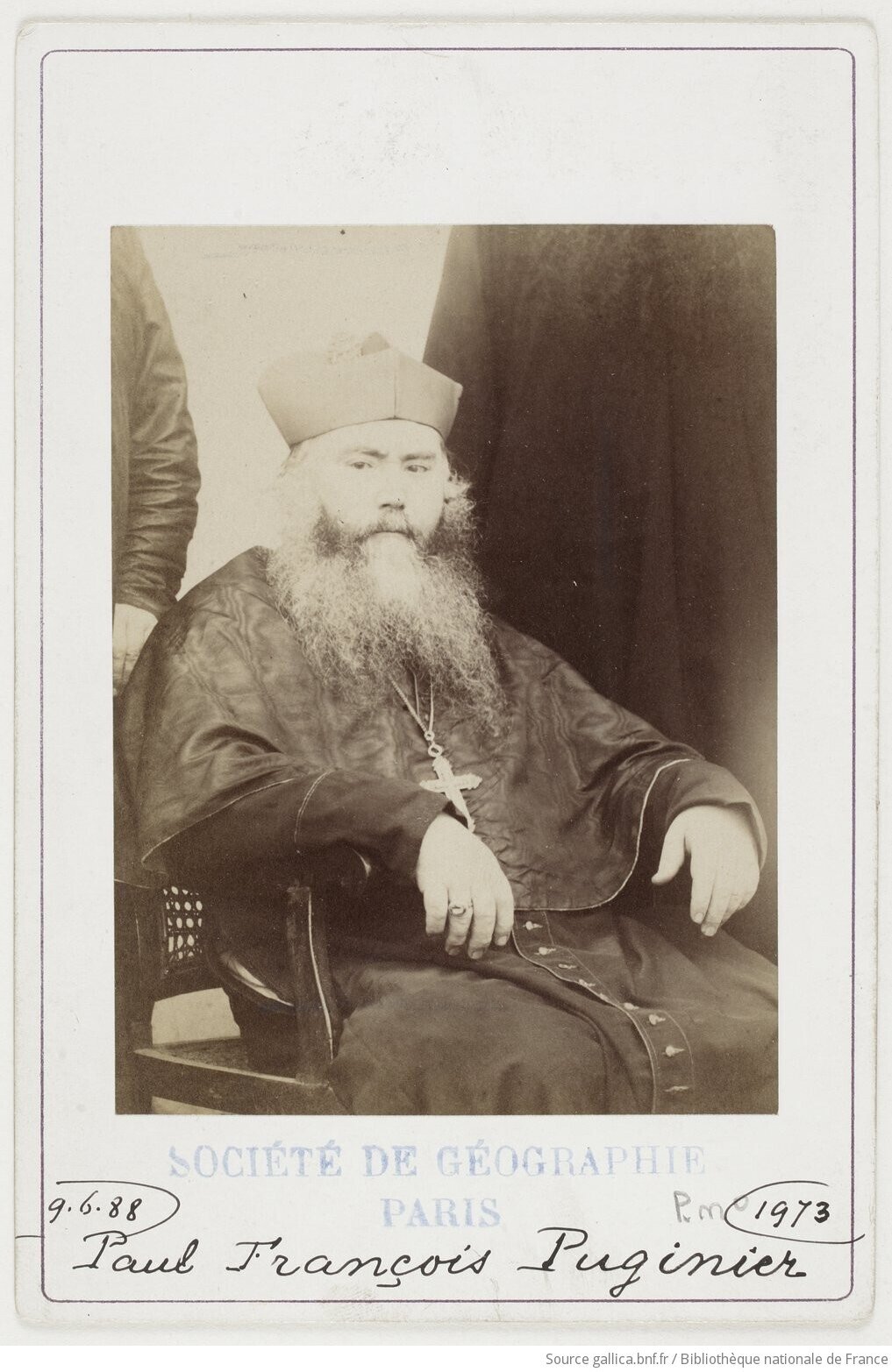

The collection we have gathered here includes the photographs screened at the author’s presentation to the Societe de geographie commerciale de Paris in February 1886. In 1888, the author gave his collection of photographs taken in Phnom Penh to the Paris Bibliotheque Nationale. While the rest of his photographic work — Java, Sumatra, Hanoi, Malaysia — is listed under his name at the French National Library, the Phnom Penh photos were indexed in a folder labeled “86 phot. de Ceylan, de Cochinchine, du Cambodge, du Tonkin, dont un portrait de Mgr Puginier, évêque du Tonkin, avec les Pères Bön et Landais, don X. Brau de Saint-Pol Lias, phot., en 1888.”

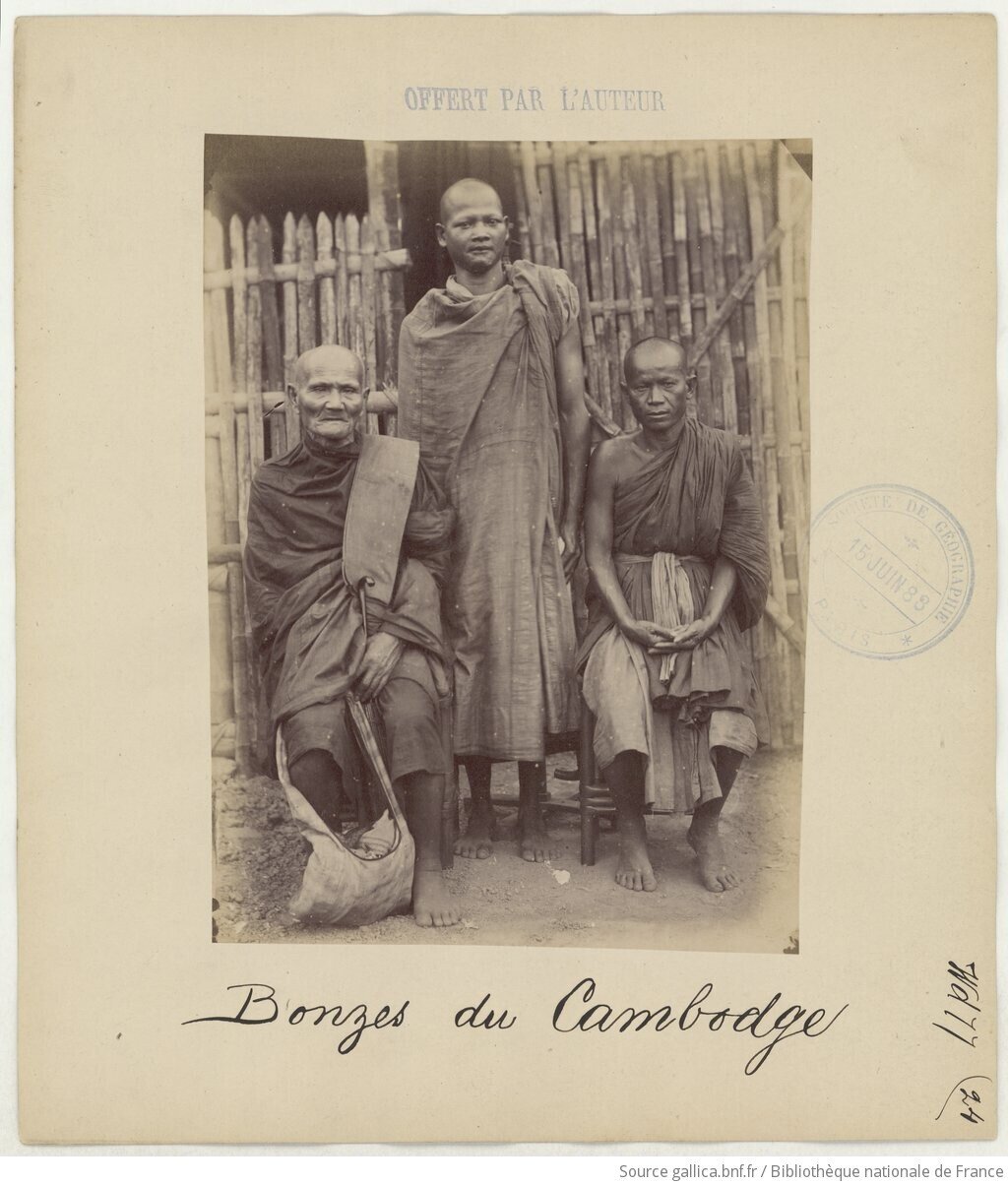

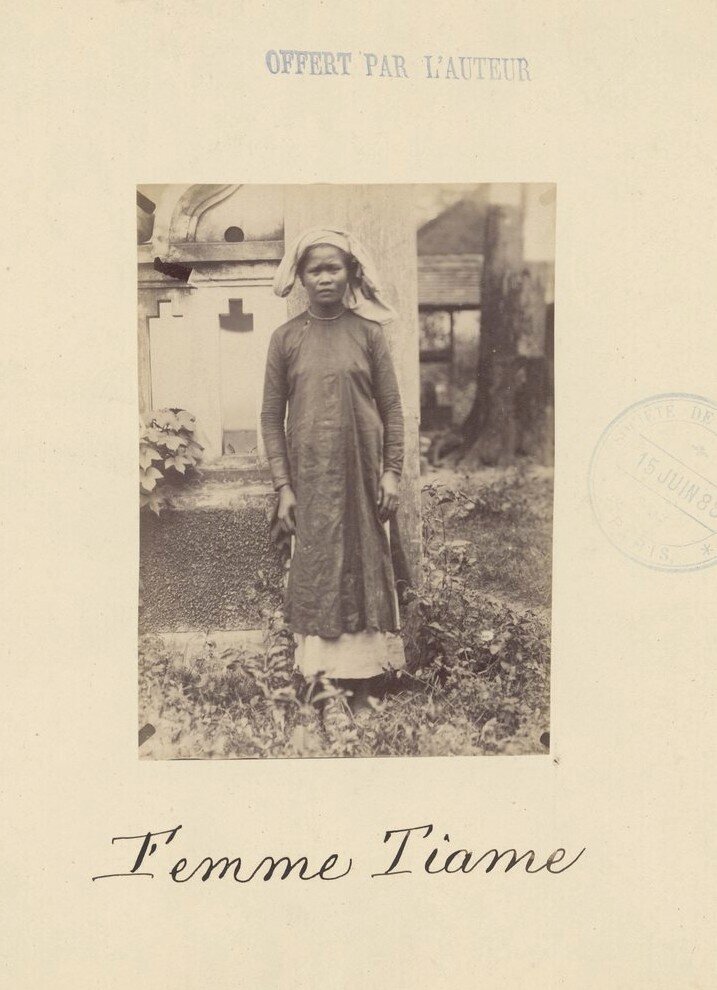

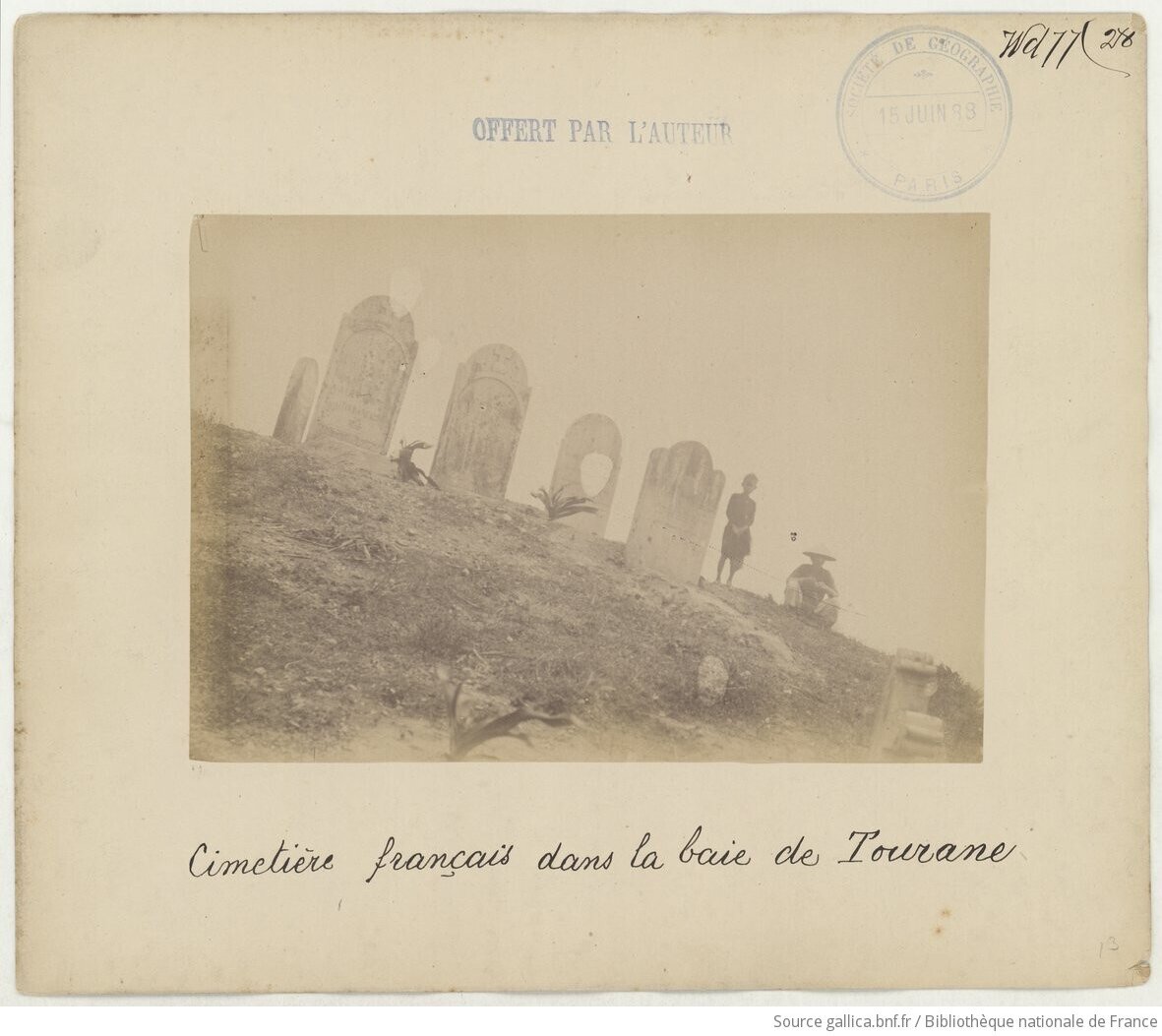

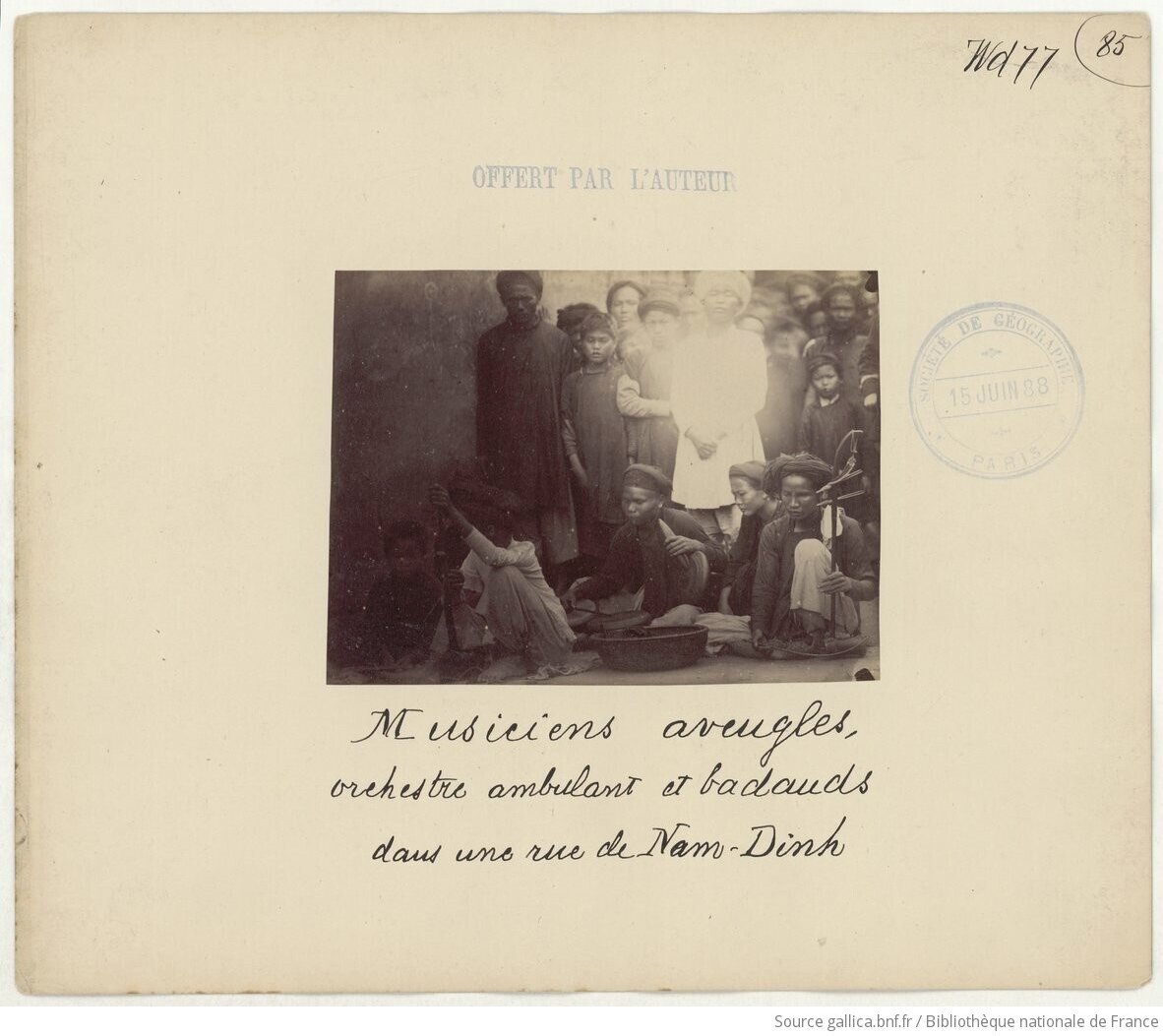

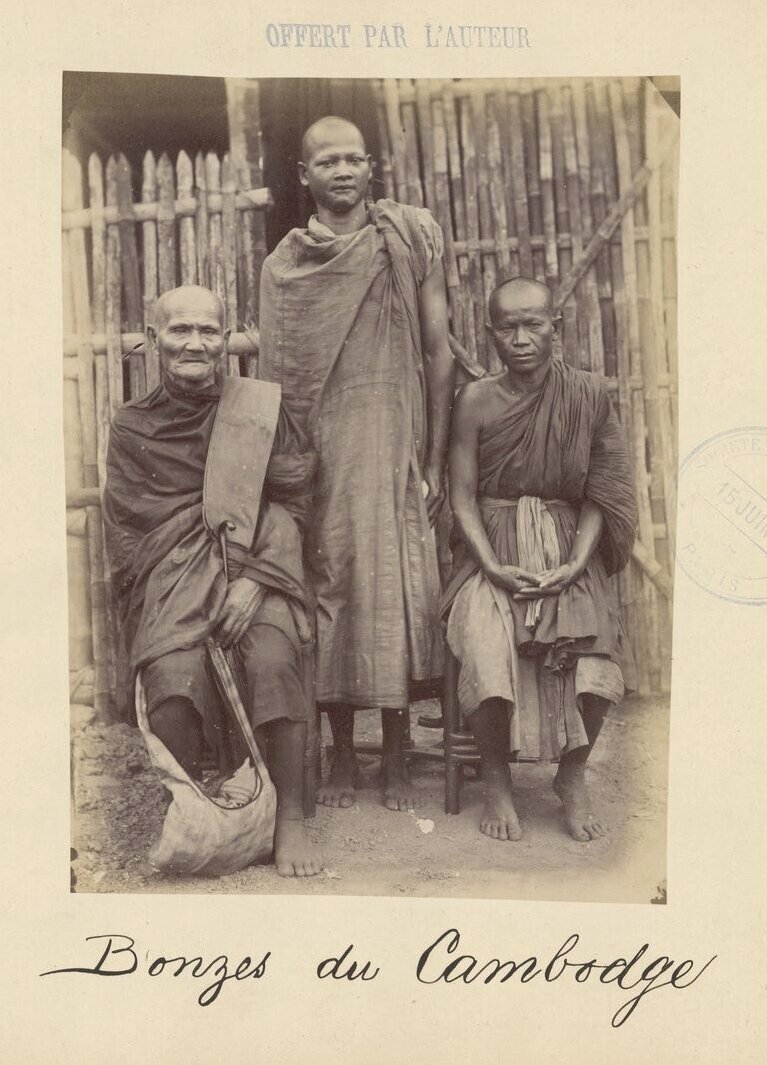

Brau de Saint-Pol Lias was a fervent amateur photographer, and if the technical quality of his photographs is far from perfect, he certainly had a photographic eye, capturing highly evocative scenes. To the Phnom Penh ones, we have added at the end of this gallery two of his shots taken shortly after, in Annam (now Vietnam), as they illustrate the haunting atmosphere he knew to conjure. His captions were meticulous, clearly handwritten.

We have organized the photographs of Phnom Penh according to the order in which he presented some of them at the above mentioned conference, and to the timeline he gave in another publication, “Feuillets détachés du journal d’un voyageur” (La Nouvelle Revue, 1885. Reed. as Phnom Penh: Journal de voyage, Magellan & Cie Éditions, 2005, Kindle Edition 2016.)

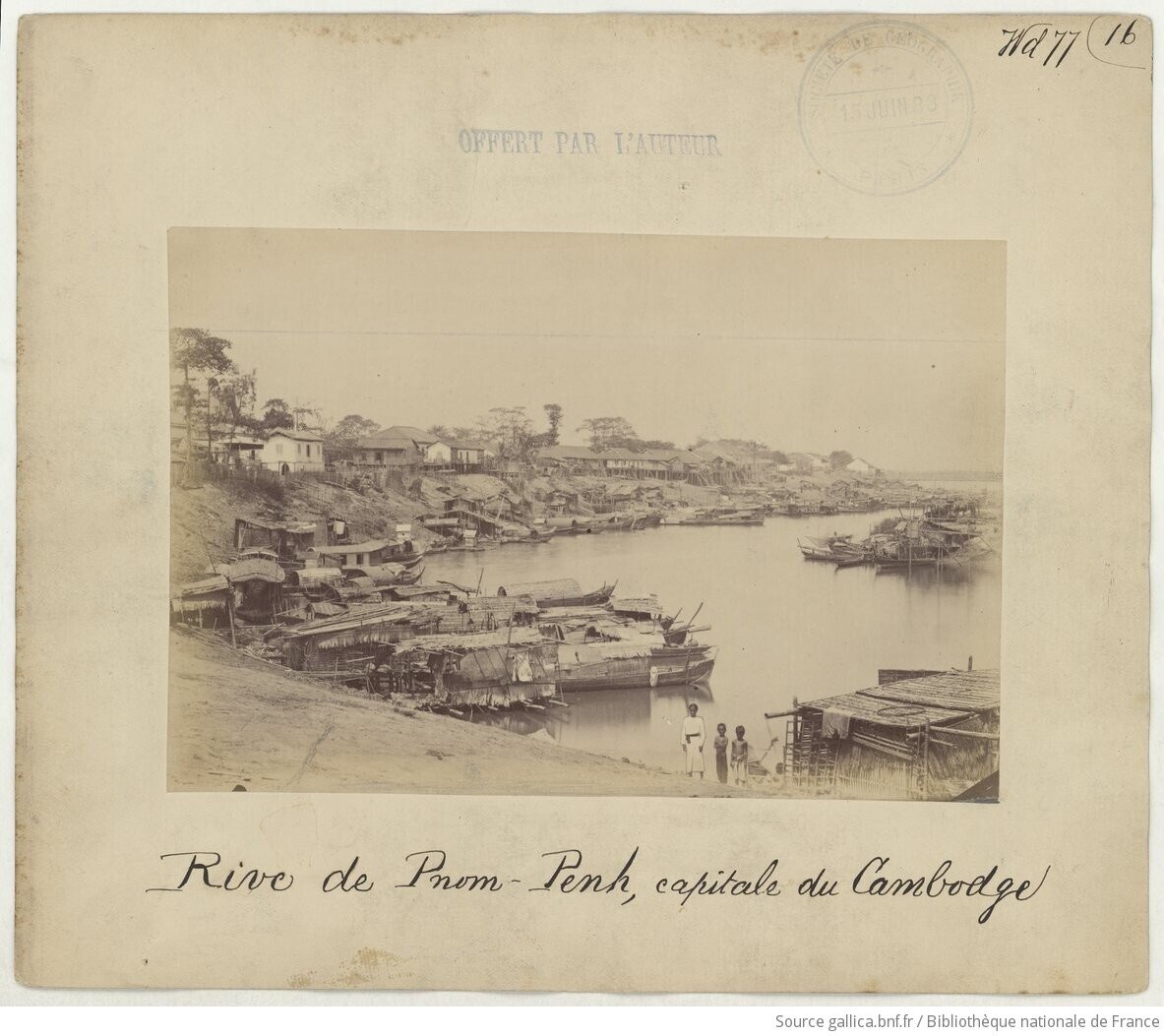

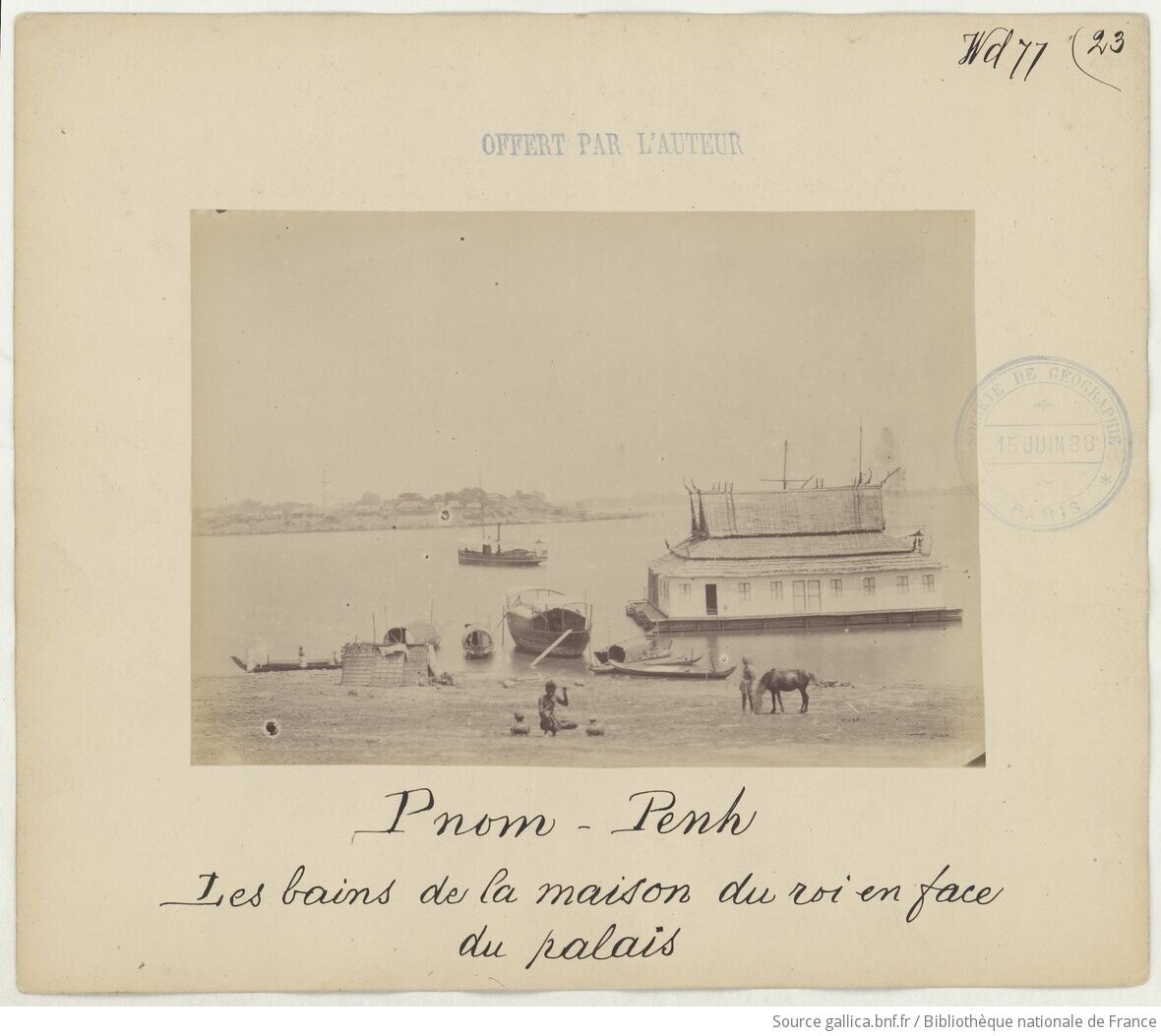

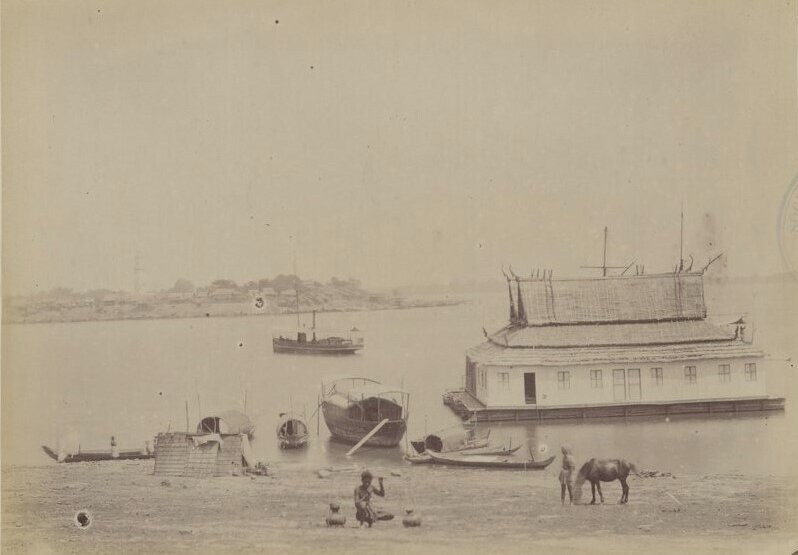

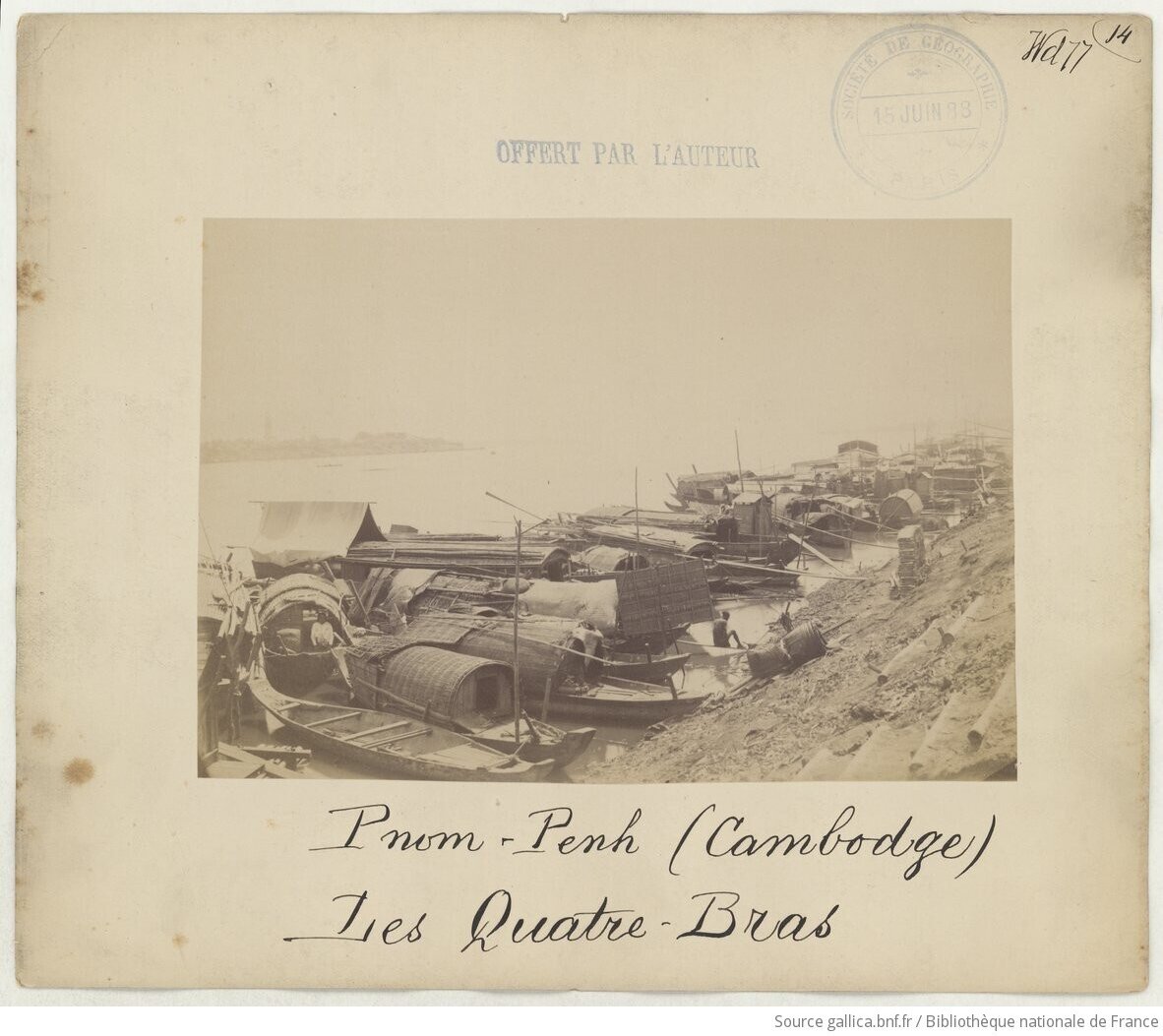

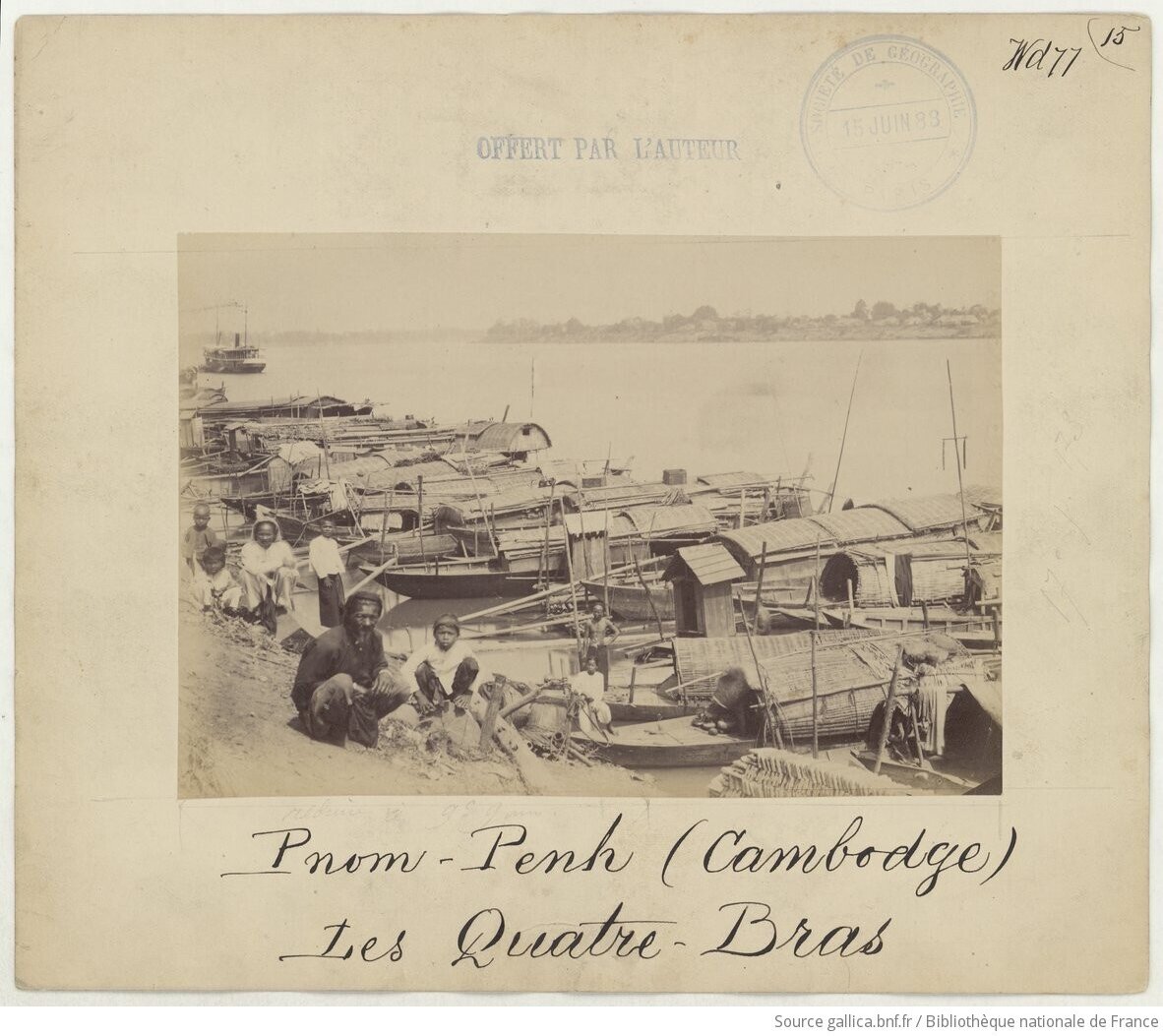

Royal baths, river banks, the Four-River city

Arriving aboard the cruiser Mouhot (after Henri Mouhot) from Saigon on 8 February 1885, the author first considered the banks and the vast expanse of water along the town. Before setting foot on the ground, he remarked “un vaste bâtiment flottant, peint en bleu, le bain du sérail de Sa Majesté, qui doit avoir de nombreuses cabines si chacune des femmes du roi à la sienne!” [“a large floating building, painted blue, the baths of His Majesty’s seraglio, which must accommodate many cabins if each of the king’s wives has her own!”

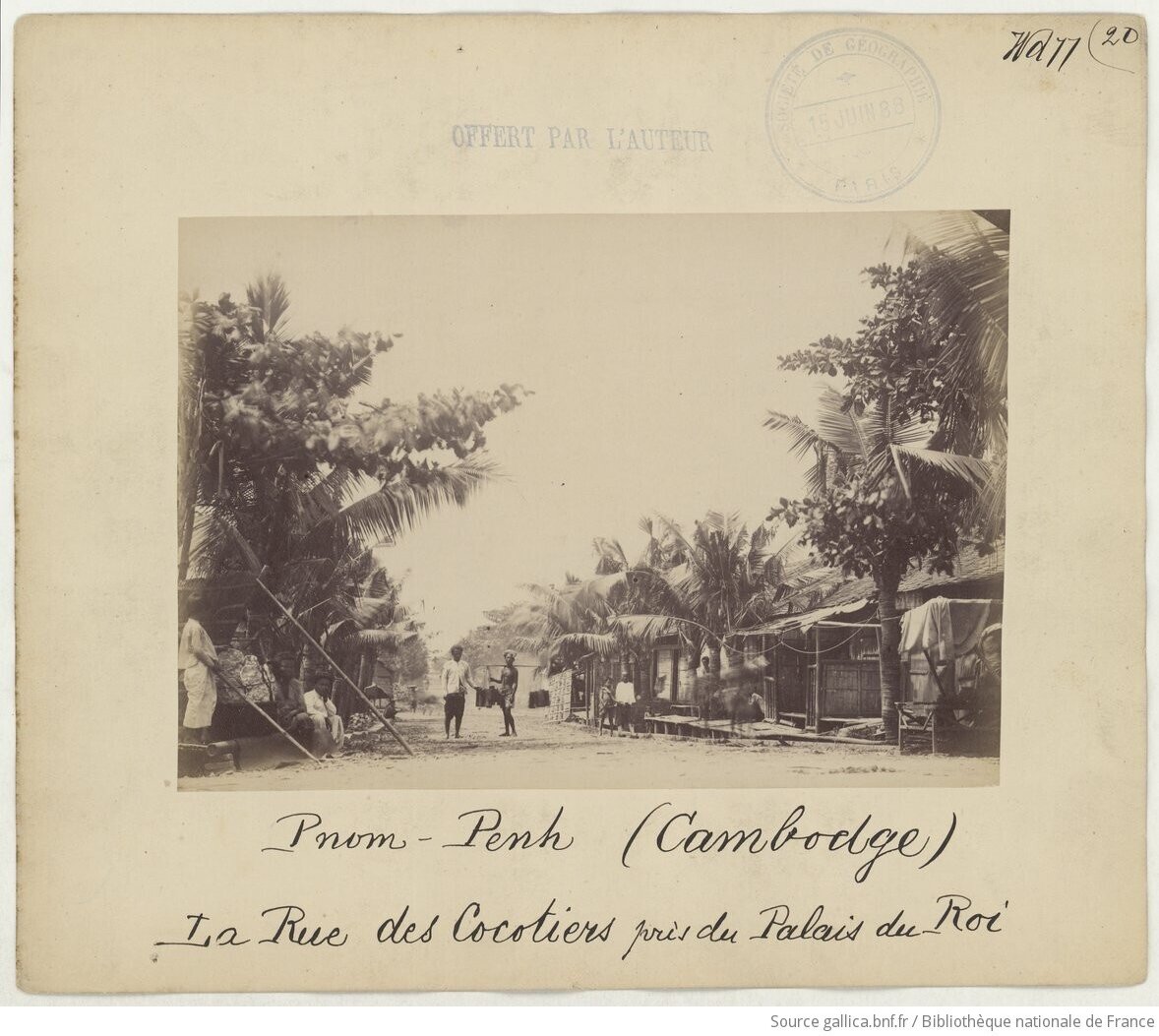

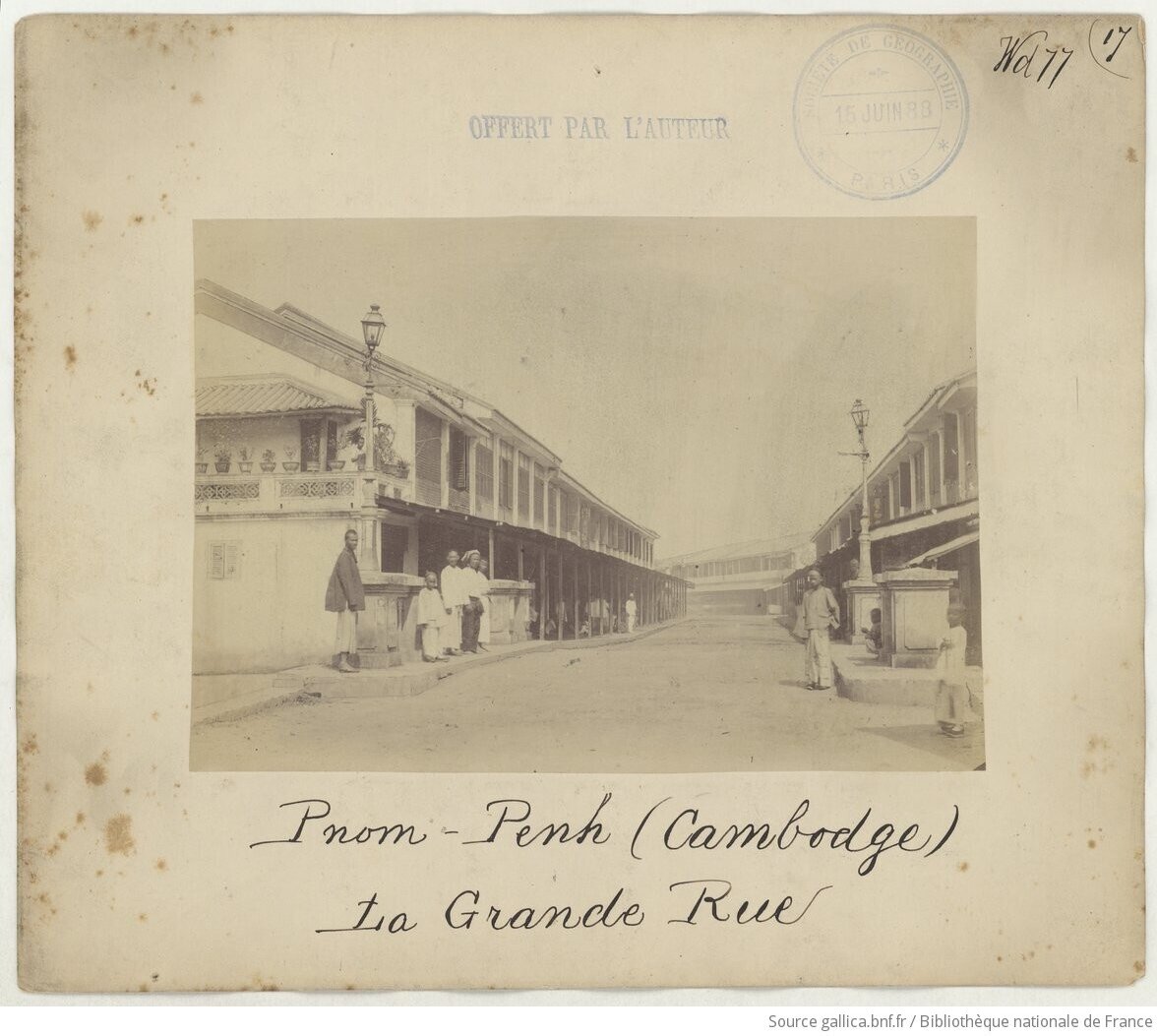

Streets and games

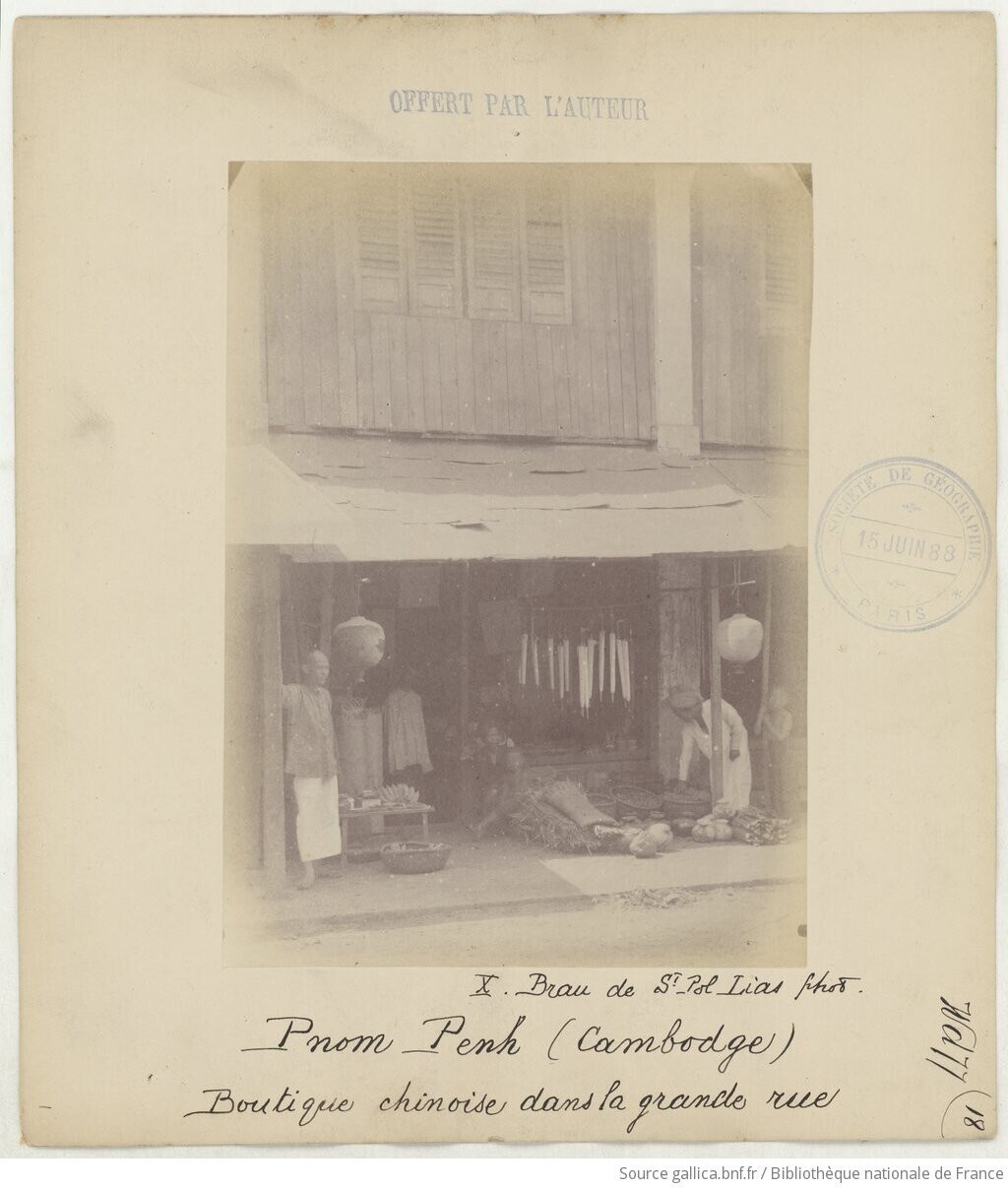

At the time, Phnom Penh two main arteries were the ‘Grande Rue’ (now Street 19, វិថី ព្រះអង្គយុគន្ធរ Preah Ang Yukhantor) and the ‘Rue des Cocotiers ou des Bananiers, close to the Palace’, probably the modern Street 240, វិថី ឧកញ៉ាឈុន Oknha Chhun). As his arrival coincided with the Lunar New Year celebrations, the author was naturally struck by the liveliness of the Chinese (and Khmer-Chinese) community in town, noting the firecrackers, the festive dinners served on the sidewalks.

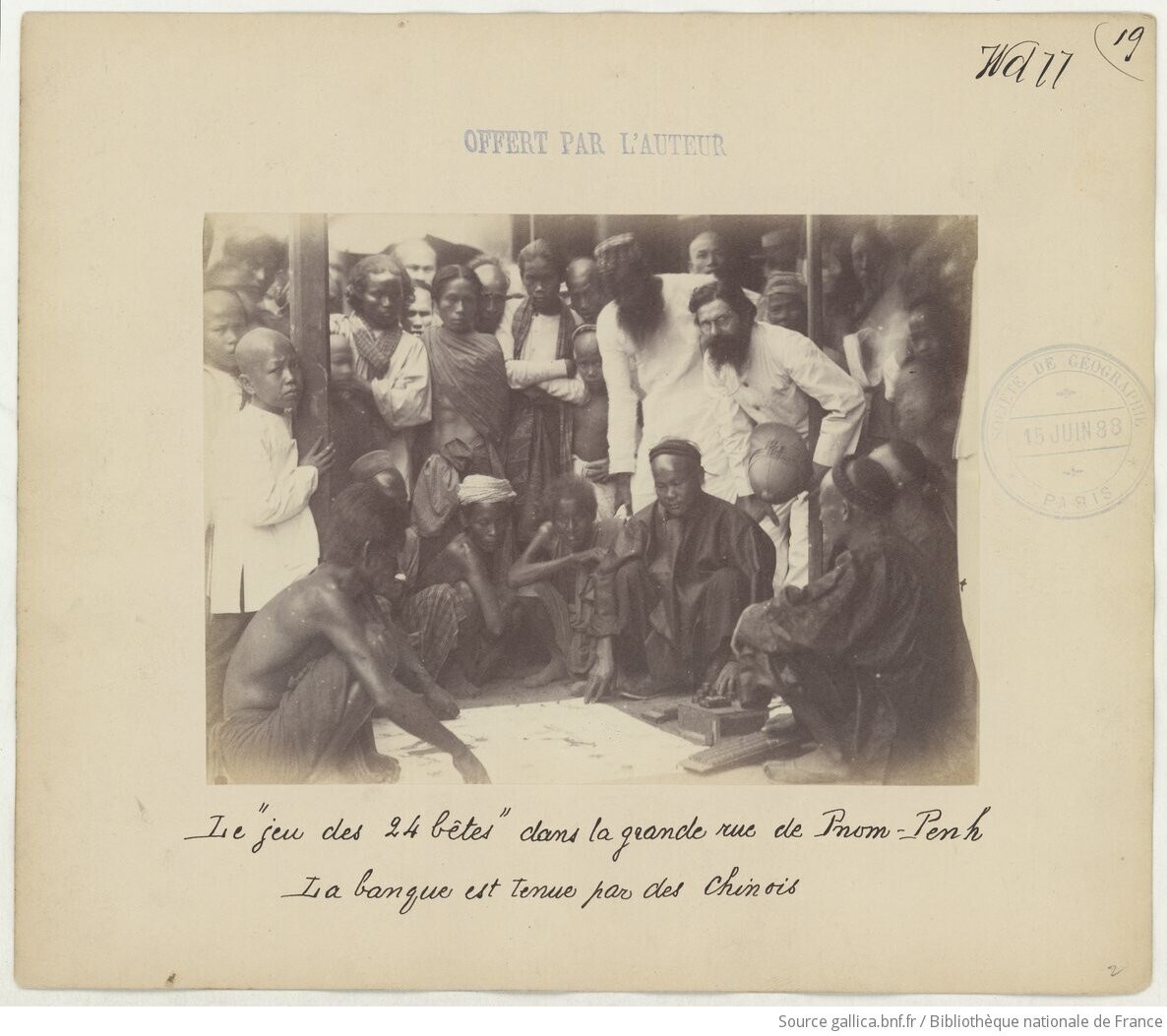

He was fascinated by two types of game of chance he called “24 Beasts” (noting on photo 10 that while the players were Cambodian, “the bankers are all Chinese), and the ‘bakouang’. The “36-Beast game”, in its Cambodian adaptation of the time-honored Chinese game 字花会 (Hua Hui or Chi Fah), was the nightmare of the colonial administrators: while the the new Protectorate Treaty of 17 June 1884 had attributed to the King the taxation revenues, the game was to be suddenly banned in May 1888, then allowed again on 27 June 1888, banned again on 29 September… In his 1885 travelogue, he noted:

Dans les rues, les trottoirs abrités sous leurs toits de planches ou de paillotes, qui se détachent du premier étage des maisons, portés par des piquets sur le bord extérieur, sont partout encombrés de joueurs. Le soir surtout, des nattes sont étendues à terre, de place en place, vivement éclairées par des lampes à huile de coco ou à pétrole. Derrière la natte, du côté des maisons, se tiennent deux Chinois qui font la banque. L’un d’eux a sous la main des sapèques, des sous et des piastres, et retire ou paie les enjeux ; l’autre a devant lui un tas de sapèques de cuivre brillant, sur lequel il passé un bol renversé, de façon à en emporter d’un coup de main habile, sous le bol qui glisse en avant sur la natte, une certaine quantité. Alors il soulève le bol et le faisant glisser de côté avec dextérité, il étale sur la natte une partie des sapèques qu’il recouvre. Un troisième personnage, le plus souvent un joueur, les compte aux yeux de tous les autres joueurs accroupis autour de la galerie qui fait cercle, debout, en détachant chaque pièce de monnaie du bout d’un rotin long de trente centimètres, sans approcher ses mains : il les groupe en paquets de quatre qu’il élimine au fur et à mesure, et, suivant que le nombre qui reste en sus est de un, de deux, de trois ou de quatre, les joueurs qui ont misé sur l’un de ces numéros ou sur plusieurs numéros combinés, ont perdu ou gagné. C’est le jeu du bakouang (ou baquang). À tout instant, en parcourant les rues, on entend, dans un de ces groupes serrés, un Chinois qui chante. On pense que c’est un joueur heureux. Pas du tout, c’est un banquier qui perd et qui compte à tous les joueurs à la ronde, d’une voix chantante, sans s’interrompre, comme s’il disait une chanson, ce qu’ils ont gagné. Il y a encore un jeu, qui se joue avec des dés, plus compliqué que le bakouang, c’est le jeu des vingt-quatre bêtes… et l’on voit cela dans tout Phnom Penh.

[“In the streets, the sidewalks sheltered under their roofs of boards or straw huts, which stand out from the first floor of the houses, supported by stakes on the outer edge, are everywhere crowded with gamblers. In the evening especially, mats are spread on the ground, here and there, brightly lit by coconut oil or kerosene lamps. Behind the mat, on the side of the houses, stand two Chinese who are acting as bankers. One of them has at hand some sapèques, sous and piastres, and withdraws or pays the stakes; the other has in front of him a pile of shiny copper sapèques, over which he passes an upturned bowl, so as to carry off with a skillful flick of the hand, under the bowl which slides forward on the mat, a certain quantity. Then he lifts the bowl and sliding it aside with dexterity, he spreads on the mat a part of the sapèques which he covers. A third character, most often a player, counts them in front of all the other players crouching around the gallery that forms a circle, standing, detaching each coin from the end of a thirty-centimeter-long rattan, without bringing his hands near: he groups them into packets of four that he eliminates as he goes along, and, depending on whether the number remaining in addition is one, two, three or four, the players who have bet on one of these numbers or on several combined numbers have lost or won. This is the game of bakouang (or baquang). At any moment, while walking the streets, one hears, in one of these tight groups, a Chinese man singing. One thinks he is a lucky player. Not at all, it is a banker who is losing and who counts to all the players around, in a singing voice, without stopping, as if he were saying a song, what they have won. There is another game, played with dice, more complicated than bakouang, it is the game of twenty-four beasts… and we see this all over Phnom Penh.”]

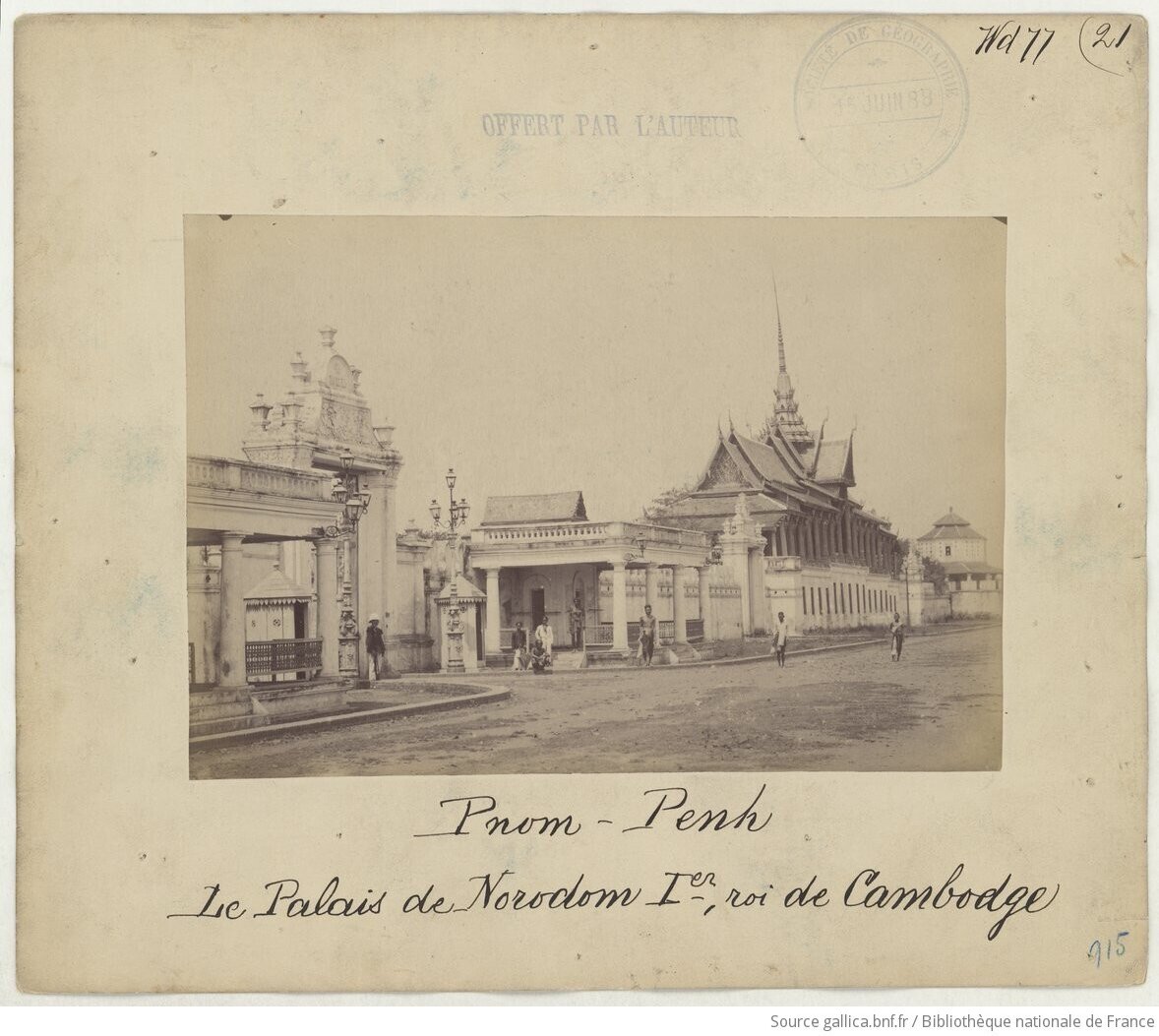

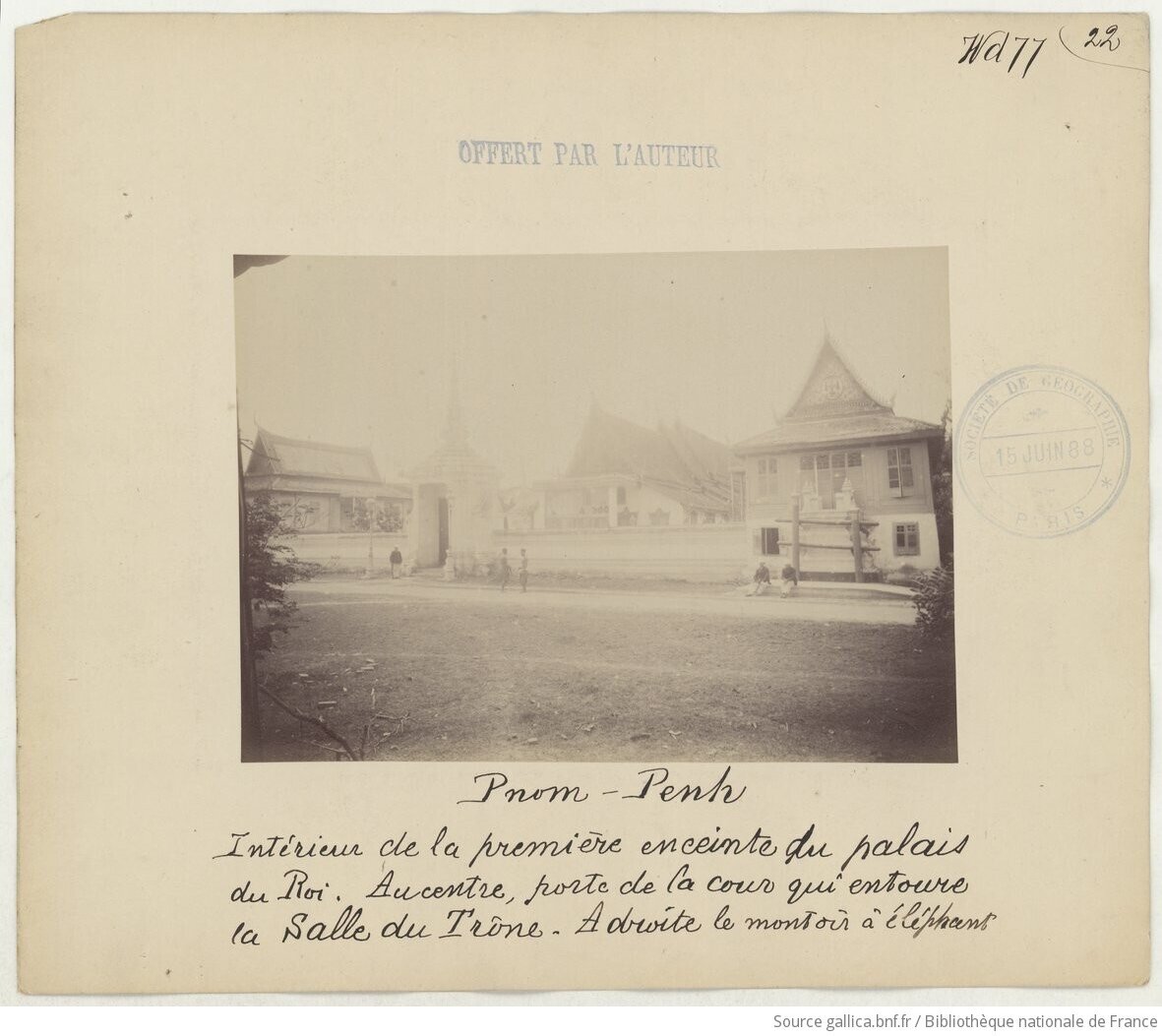

Royal Palace

The author took his time in visiting Phnom Penh Royal Palace, in particular the Throne Hall, and he aptly noted the function of transition between the inner palace and the second and first precincts played by the Iron Pavilion, where King Norodom I welcomed his foreign guests. His annotations are to the point, like on photo 8: “Interieur de la première enceinte du palais du roi. Au centre, porte de la cour qui entoure la Salle du Trone [First precinct of the royal palace. Center, gate to the courtyard surrounding the Throne Hall].”

He noticed an important clog in the machinery of the Royal Palace:

La cuisinière du roi est, à Phnom Penh, un personnage dont l’influence s’étend bien au-delà de sa cuisine. C’est une vieille Siamoise attachée depuis bien longtemps au service de Sa Majesté dont elle a toute la confiance et qui a joué, plus d’une fois, assure-t-on, un rôle politique important. Une voiture de Norodom vient la prendre tous les matins chez elle pour la conduire au palais. Mais, quelle que soit la curiosité que puisse inspirer une si importante personne, ce n’est pas elle que je cherche en ce moment sur la rive avec ma lorgnette…

[“The King’s cook is, in Phnom Penh, a personage whose influence extends far beyond her kitchen. She is an old Siamese woman who has long been attached to the service of His Majesty, who enjoys his full confidence, and who has played, more than once it is said, an important political role. A Norodom carriage comes to pick her up every morning at her home to take her to the palace. But, whatever curiosity such an important person may inspire, it is not her that I am looking for at this moment on the bank with my spyglass…

The city outskirts

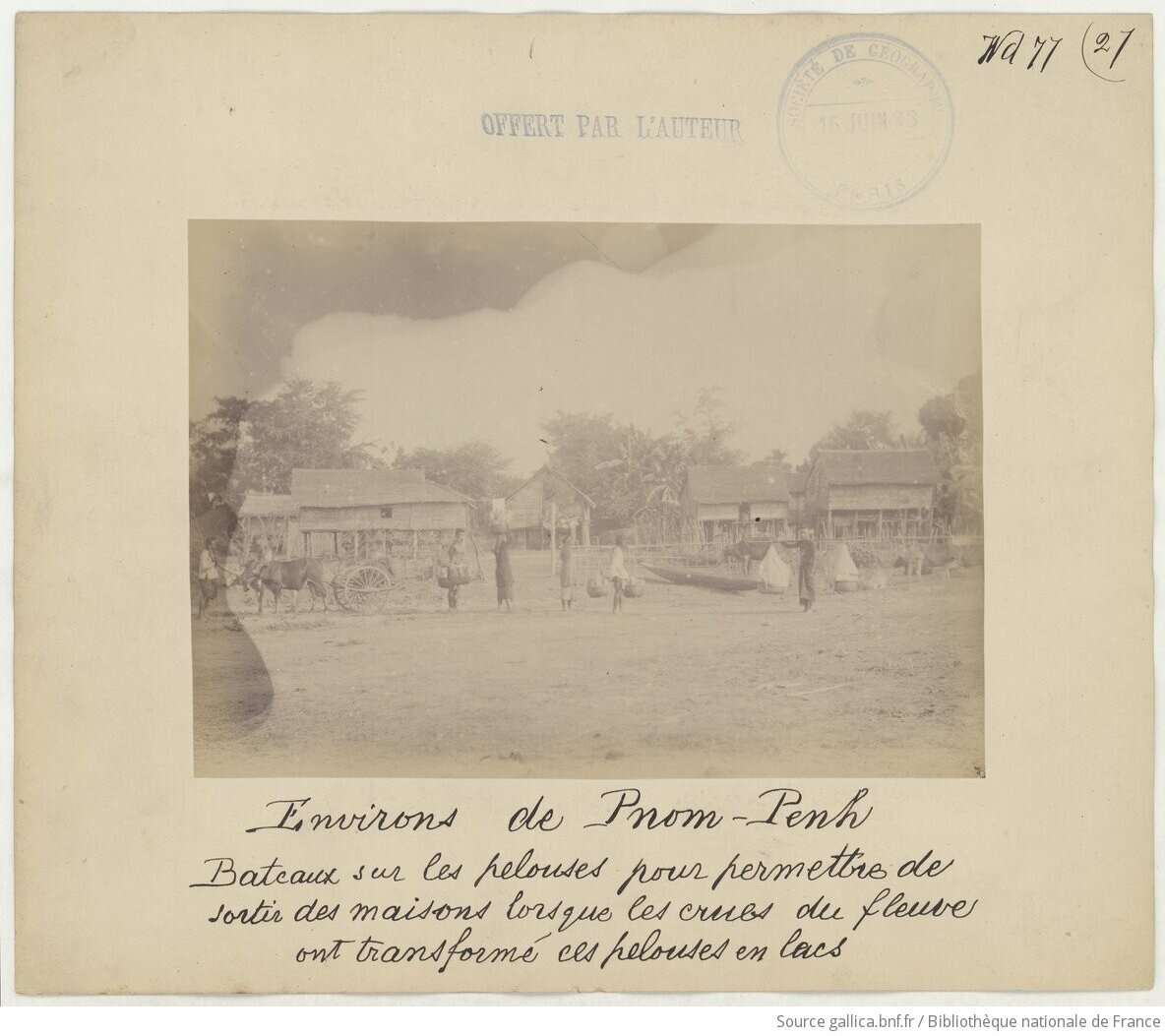

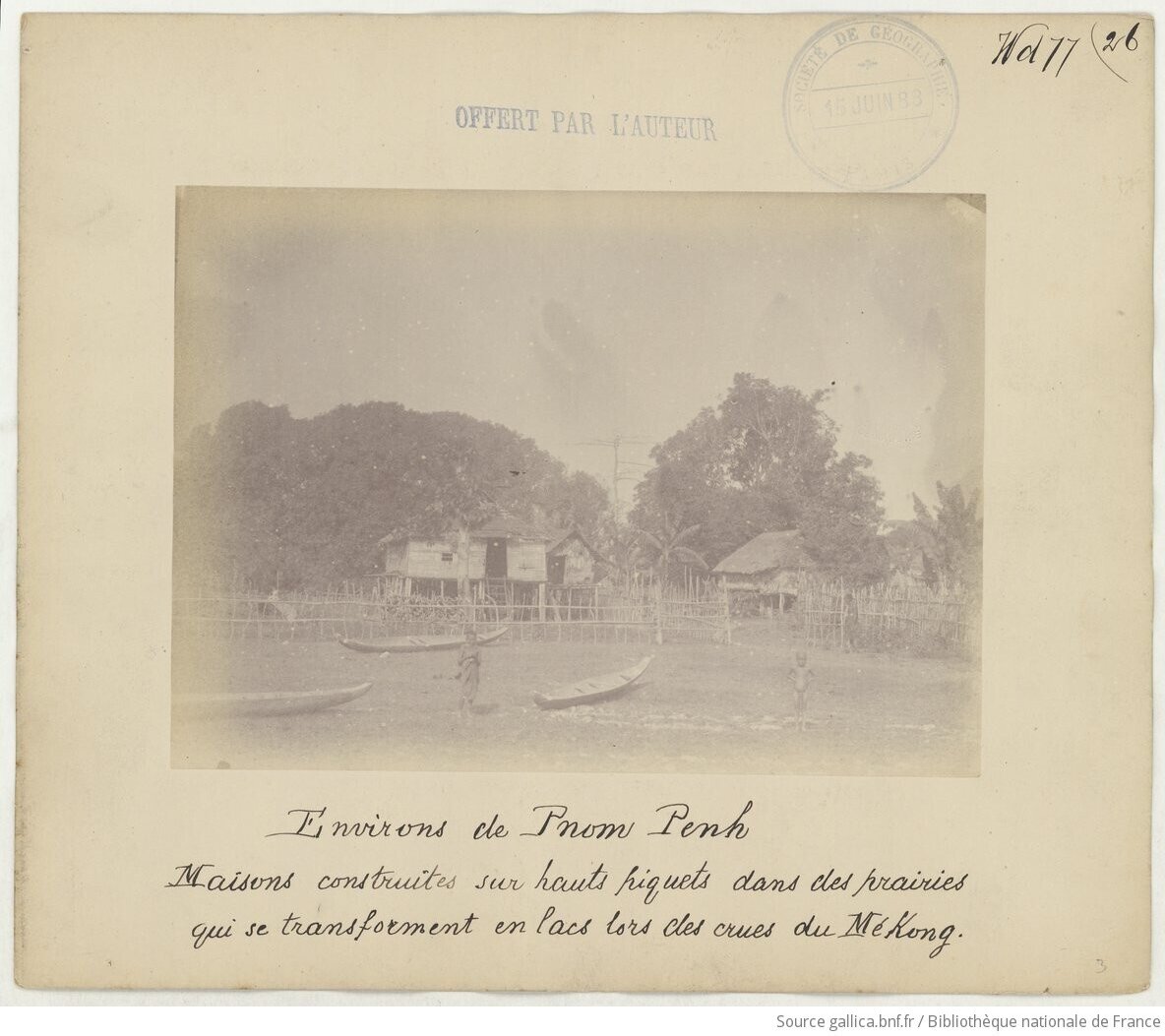

As the Sivutha revolt was raging, the author could only take his camera to the villages close to Phnom Penh. His photo captions — photos 12, 13, 14 -, he gave indications on how villagers managed to deal with monsoon floodings. In his travelogue, he noted:

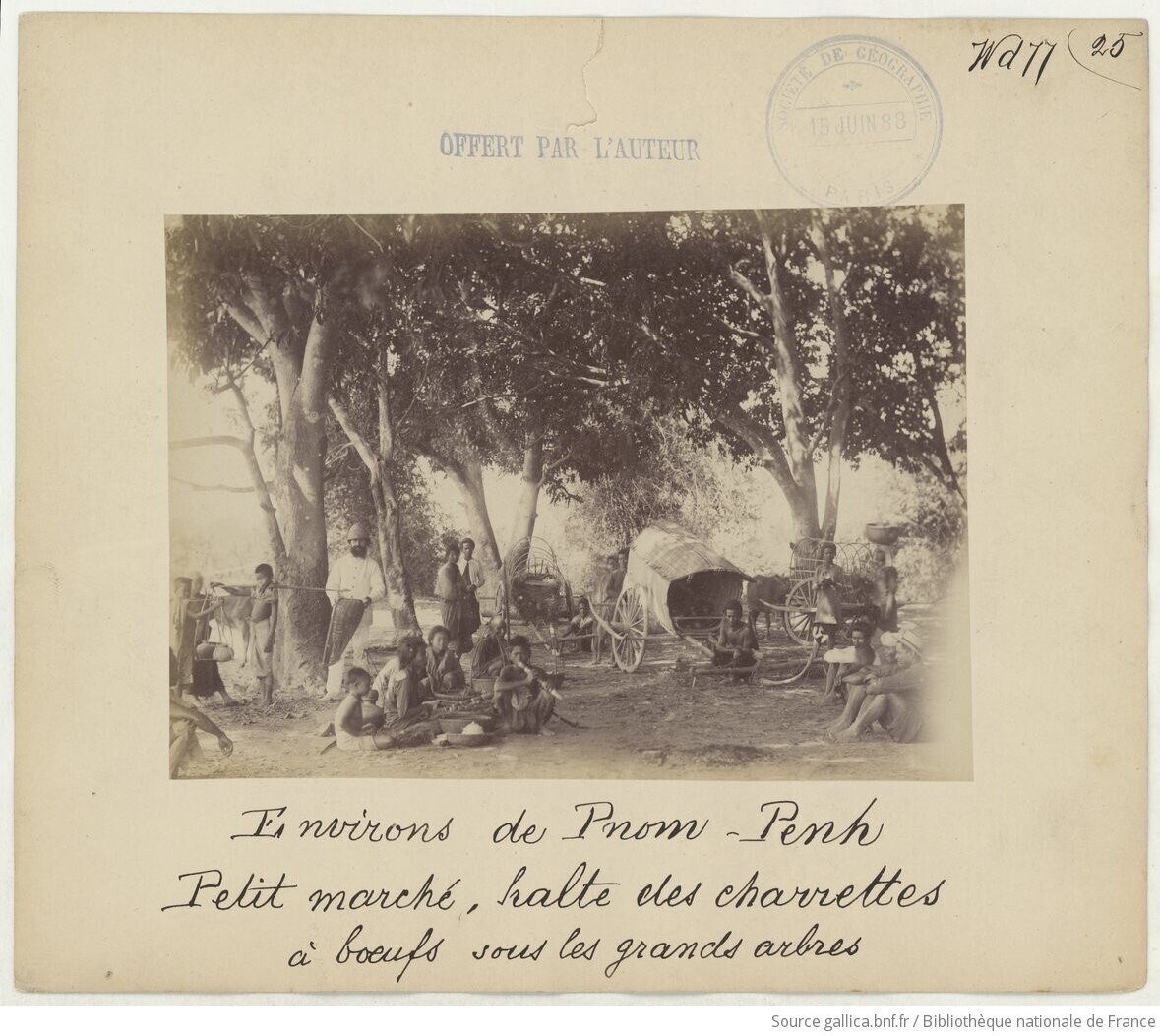

Samedi 14 février 1885. – Je vais ce matin jusque dans la campagne prendre une photographie des environs de Phnom Penh. Partout, autour des paillotes construites au milieu des prés, je remarque des pirogues déposées sur le gazon. C’est que ces prés, par les hautes eaux, se transforment en lacs, et alors les habitants suspendent leurs légères petites charrettes sous leur plancher élevé sur piquets à deux mètres au-dessus du sol et sortent de chez eux en pirogues pour vaquer à leurs affaires. Je m’arrête un moment à un petit marché de fruits et de boissons, improvisé sous de grands arbres sur le bord d’un chemin, et je vois passer là de longues files de ces petites charrettes couvertes ou découvertes, traînées par des bœufs qui vont au trot en soulevant des tourbillons de poussière. Elles viennent toutes de l’intérieur chargées de provisions pour le marché, de pastèques vertes surtout. Cette affluence de campagnards est de très bon augure. Si des bruits de guerre couraient dans le pays, si le mouvement annoncé devait avoir lieu, ils en sauraient certainement quelque chose et né viendraient pas ainsi à la ville.

[“Saturday, February 14, 1885. – I am going this morning into the countryside to take a photograph of the area around Phnom Penh. Everywhere, around the straw huts built in the middle of the meadows, I notice canoes placed on the grass. This is because these meadows, due to high water, are transformed into lakes, and then the inhabitants suspend their light little carts under their raised floor on stakes two meters above the ground and leave their homes in canoes to go about their business. I stop for a moment at a small market of fruits and drinks, improvised under large trees on the edge of a road, and I see long lines of these small carts pass by, covered or uncovered, pulled by oxen that go at a trot, raising whirlwinds of dust. They all come from the interior loaded with provisions for the market, especially green watermelons. This influx of country people is a very good omen. If rumors of war were to circulate in the country, if the announced movement were to take place, they would certainly know something about it and would not come to the city in this way.”]

A missed photo-op: Angkor

Two members of the four-strong mission, viscounts d’Osmoy and de Chabannes, had managed to travel to Battambang and Siem Reap before the situation deteriorated. In his travelogue, the author had to content himself with passing on their travel accounts. About Battambang governor entourage and the multi-ethnic fabric of the city:

Le vice-roi de Battambang, dans un accès de jalousie, a fait décapiter un de ses fils, et pour être bien sûr de sa vengeance sauvage, il a eu le monstrueux courage d’assister à l’exécution ! Sa jalousie est telle que, pour conduire ses danseuses, il n’a qu’un orchestre de femmes. Ce jour-là, à cause de l’importance de la fête, il y avait aussi, au palais, un orchestre d’hommes, celui d’un de ses fils. Les danseuses étaient cambodgiennes, siamoises, birmanes, malaises et laotiennes, chaque race facile à distinguer par sa coiffure spéciale, toute différente des autres. De nombreuses députations venaient, pendant la fête, saluer le gouverneur : c’était d’abord celle des mineurs birmans de sa province, puis les Malais, les Malabars, les Laotiens, les Kouys.

[“In a fit of jealousy, the Viceroy of Battambang had one of his sons beheaded, and to be sure of his savage vengeance, he had the monstrous courage to attend the execution! His jealousy is such that, to conduct his dancers, he has only a women’s orchestra. That day, because of the importance of the festival, there was also, at the palace, a men’s orchestra, that of one of his sons. The dancers were Cambodian, Siamese, Burmese, Malay and Laotian, each race easily distinguished by its special hairstyle, completely different from the others. Many deputations came, during the festival, to greet the governor: first of all, that of the Burmese miners of his province, then the Malay, Malabar, Laotians, Kouy people.”]

About Siem Reap, Angkor Wat, Angkor Thom and the Leper King:

De Siem Reap à Angkor Vat, on met trois heures, traversant de magnifiques forêts par des chemins qui ont tout juste la largeur nécessaire à une charrette. Là, on descend à la sala, maison ouverte, sur hauts piquets, pour recevoir les étrangers, et on va à la pagode voisine où l’on trouve généralement un guide, un bonze qui vous conduit aux ruines, pendant que les bœufs ou les buffles dételés vont paître en liberté dans la forêt. Angkor Vat est une immense pagode présentant un carré d’environ mille cinq cents mètres de côté, soutenu par un mur de dix mètres de haut sur tout le pourtour, entouré d’un fossé qui a peut-être cent mètres de large ; tout cela a été exactement mesuré et est bien connu, grâce aux Doudart de Lagrée, aux Mouhot, aux Garnier, aux Delaporte, aux Aymonnier, aux Moura, aux Pavie. L’intérieur a plusieurs enceintes, des piscines, des sanctuaires, des galeries, des tours superposées, revêtus des plus admirables sculptures : on né voit pas de ruines plus grandioses, plus imposantes ; l’harmonie de l’ensemble est telle que ses proportions gigantesques n’apparaissent que lorsqu’on est au pied du monument. […] Dans la forêt splendide qui occupe l’enceinte d’Angkor Thom, enceinte très vaste qui a dix kilomètres peut-être, on trouve, outré le palais de Bayon, çà et là, de magnifiques statues de monstres, de dragons, de dieux et de personnages dont la plus belle est le Roi lépreux. On dit qu’on a offert au Siam quatre millions de la statue de ce roi lépreux qui, d’après la légende, aurait fait construire la pagode d’Angkor Vat (watt, pagode) ayant fait vœu, s’il guérissait, comme le lui avait promis un bonze, d’y élever un monument qui ferait l’admiration de l’univers.

[“It takes three hours from Siem Reap to Angkor Wat, crossing magnificent forests by paths that are just wide enough for a cart. There, one goes down to the sala, an open house on high stakes to receive strangers, and one goes to the neighboring pagoda where one generally finds a guide, a monk who leads one to the ruins, while the unharnessed oxen or buffaloes go to graze freely in the forest. Angkor Wat is an immense pagoda presenting a square of about one thousand five hundred meters on each side, supported by a wall ten meters high all around, surrounded by a moat that is perhaps one hundred meters wide; all this has been exactly measured and is well known, thanks to the Doudart de Lagrée, the Mouhot, the Garnier, the Delaporte, the Aymonnier, the Moura, the Pavie. The interior has several enclosures, pools, sanctuaries, galleries, superimposed towers, covered with the most admirable sculptures: one does not see ruins more grandiose, more imposing; the harmony of the whole is such that its gigantic proportions only appear when one is at the foot of the monument. […] In the splendid forest which occupies the enclosure of Angkor Thom, a very vast enclosure which is perhaps ten kilometers, one finds, besides the palace of Bayon, here and there, magnificent statues of monsters, dragons, gods and characters of which the most beautiful is the Leper King. It is said that four million [of piasters? francs?] were offered to Siam for the statue of this leper king who, according to legend, had built the pagoda of Angkor Wat (watt, pagoda) having made a vow, if he were cured, as a monk had promised him, to raise there a monument which would be the admiration of the universe.]