Au Tonkin, en Cochinchine et au Cambodge

by Xavier Brau de Saint-Pol Lias

A staunch proponent of French colonialist expansion taking in the state of affairs in Indochina during the troubled mid-1880s.

- Publication

- Bulletin de la Société de Géographie commerciale de Paris, vol 8, 1 Oct 1885-1886, p 11-27. via gallica.bnf.fr

- Published

- 1886

- Author

- Xavier Brau de Saint-Pol Lias

- Pages

- 17

- Language

- French

pdf 661.0 KB

“La politique des peuples devient de plus en plus aujourd’hui une politique économique, et la question coloniale

prend de jour en jour une place plus grande dans cette politique” [“The politics of the nations is becoming more and more an economic one nowadays, and the colonial question is taking by the day a greater place in this policy”] : the preamble of this communication to the Societe de geographie commerciale of Paris couldn’t have been clearer. Relating his journey through Tonkin, Cochinchina and Cambodia from October 1884 to March 1885, the author focused on the economic potential of already restive colonies in mainland Southeast East Asia.

At a time when the extorstionist policy in French Indochina was decried in Paris and even Saigon, Hanoi or Phnom Penh, and the new Protectorate forced upon King Norodom I in November 1884 was met with hostility by the Cambodian elites and farmers, the communication insisted on the fast paced economic development of the area, in particular Cochinchina where intensive monoculture of gutta-percha (the ancestor of latex) had started:

La population de l’Annam et du Tonkin est de 15 à 16 millions d’habitants, peut-être faudrait-il dire 20 millions.

Cette population intelligente, active, très industrieuse, pourrait permettre de refouler l’invasion chinoise, je parle de l’invasion pacifique, plus dangereuse peut-être gue l’invasion guerrière. En Cochinchine, par exemple, les Chinois tiennnt entre leurs mains toute l’industrie; et tout l’argent produit par l’industrie va en Chine. On aurait donc, au Tonkin, l’argent qui serait produit par le pays ; cet argent resterait dans lepays. Le roi d’Annam enfin tire aujourd’hui du Tonkin 15 à 16 millions de piastre pr le système d’impôt qu’il appliquait autrefois à la Cochinchine .…Voit-on maintanant, par le calcul le plus élémentaire des probabilités, quel chiffre pourrait alleindre le budget du Tonkin et de l’Annam entre les mains d’une administration qui a porté les revenus de la Cochinchine de 1600 000 francs à 42 millions dans ces conditions infiniment moins favorables que celles où elle serait placée au Tonkin.

[The population of Annam and Tonkin is 15 to 16 million inhabitants, perhaps we should say 20 million. This intelligent, active, very industrious population could allow us to repel the Chinese invasion, I am talking about

the peaceful invasion, perhaps more dangerous than the warlike invasion. In Cochinchina, for example, the Chinesehold in their hands all the industry; and all the money produced by the industry goes to China. We would therefore have, in Tonkin, the money that would be produced by the country; this money would remain in the country. The King of Annam draws today from Tonkin 15 to 16 million piastres for the tax system that he formerly applied to Cochinchina.…We can now see, by the most elementary calculation of probabilities, what figure could allocate the budget of Tonkin and Annam in the hands of an administration which has increased the revenues of Cochinchina from 1,600,000 francs to 42 millions in these conditions infinitely less favorable than those in which it would be placed in Tonkin.] (p 22)

Quite candidly, the author allowed that, apart from a short stay in Phnom Peng, he was unable to join the three other members of the visiting commission in their exploration of Cambodia due to the unrest in the Kingdom. He was to recount in another publication (“Pages detachees du journal d’un voyageur”, La Nouvelle Revue, Paris, 1885) how he reached Phnom Penh onboard the small (but auspiciously named) cruiser Mouhot on 8 February 1885, Sunday. In his conference, he took the opportunity to pay a vibrant tribute to the Mission Pavie:

Quelques jours après notre arrivée à Saigon, MM. de Chabanne et de Lacroix s’embarquaient pour le Cambodge et arrivaient à Phnom-Pènh montés à dos d’éléphant. De là, ils allaient à Oudong et se rembarquaient pour descendre le fleuve ou pour le remonter jusqu aux lacs. Il faut vous dire en effet que ce qu’on appelle le bras des lacs est un des fleuves les plus extraordinaires que l’on puisse voir : pendant une partie de l’année il coula dans un sens, et pendant une autre partie il coule dans un autre, c’est-à-dire qu’il va tantôt de Phnom-Pènh aux lacs et tantôt des lacs à Phnom-Pènh. Ces messieurs continuèrent leur .exploration jusqu’à Battambang et à Angkor, les deux provinces malheureusement siamoises, puisque le Cambodge a cédé ces deux belles parties de son territoii·o au Siam, et ils revinrent de là à Oudong pour y· ëtudier, d’après de nombreux renseignements pris dans le pays, la possibilité de la fondation d’un établissement agricole et industriel, ce qui était le but principal de leur voyage.

À la même époque, ou plutôt quelques jours après le départ de MM. de Chabannes et de Lacroix, M. de Llamby

partait à son tour pour le Cambodge, mais pour y faire une exploration toute différente: il se proposait de remonter d’abord le grand fleuve, puis de descendre à Kampot et de visiter surtout la région montagneuse qui avoisine Kampot et qui, probablement, d’après les indices de sa configuration, est une region minière, mais que l’on n’a pas encore explorée. Malheureusement, ce projet intéressant fut entravé par la grande insurrection qui commença par la prise du poste de Sambor et qui s’étendit rapidement sur tout le pays.Pendant ce temps, M. Je vicomte d’Osmoy étudiait à Saigon un projet qui aurait pu allpeler en Cochinchine, suivant ses vues, des capitaux français importants, et ajouter un lien de plus aux rares liens commerciaux et industriels qui unissent Ia Cochinchine à la France.· Mais les affaires, au Cambodge, s’aggravaient de plus en plus, et mes compagnons de voyage étaient immobilisés à Phnom-Pènh. Ils né voulaient pourtant pas quitter le Cambodge et les Français, encore peu nombreux, qui les avaient très cordialement accueillis dans ce pays, à un moment qui semblait devenir très périlleux, et et ils m’écrivirent au commencement du mois de février que leur ‑départ semblerait une désertion et qu’ils désiraient y continuer encore leur séjour.

MM. de Chabannes et de Lacroix, qui avaient offert leurs services d’officiers au colonel commandant au Cambodge, avaient pu même faire partie d’une reconnaissance et avaient fait le coup de feu aux environs de Phnom-Pènh. Dans ces conditions, j’allai les rejoindre. Une insurrection était annoncée pour le jour de l’an chinois, c’est-à-dire pour le 15 février; mais la bande, ayant été dispersée à quelques kilomètres de Phnom-pènh, le pays recouvra sa tranquillité.

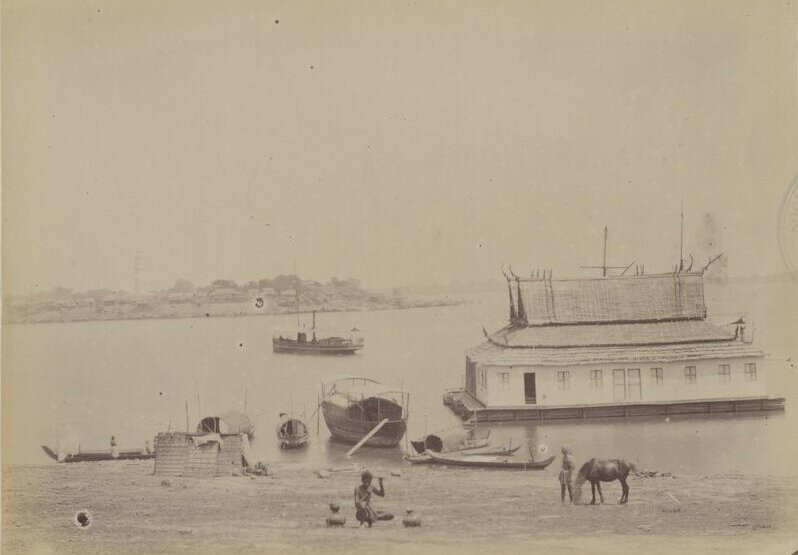

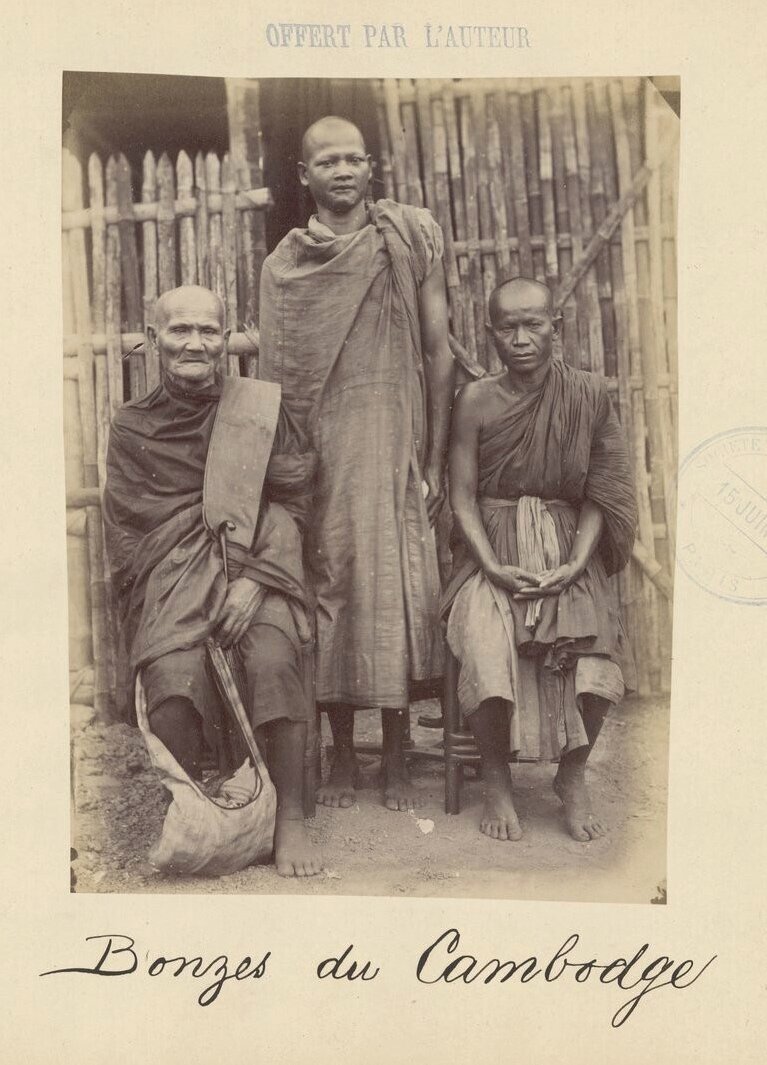

Ce jour de fête, qui paraissait si menaçant, et où l’insurrection devait éclater, fut un jour tranquille, pendant lequel j’ai pu prendre du Cambodge des photographies que je vais avoir l’honneur de faire passer sous vos yeux, du moins quelques-unes, car j’ai été obligé de choisir dans celles que j’avais sous la main, ma collection n’étant pas encore à ma disposition. Mais je dois dire avant cela que le Cambodge me paraît de toutes nos possessions d’Indo-Chine le pays qui peut se prêter le plus immediatement à la colonisation. Il a des terres extrêmement fertiles où de riches cultures ont éte tentée; l’ expérience du travail des Cambodgiens y a éte faite aussi et d une façon concluante, par M. Pavie, qui assiste à cette séance, et auquel je suis heureux de pouvoir apporter ici mon hommage pour le bien qu’il a accompli dans ce pays. M. Pavie a courageusement jalonné le Cambodge; c’est lui qui a planté à travers ce pays tous les piquets de la ligne télégraphique qui va de Saïgon à Bangkok (Applaudissements) et il a accompli seul ce grand travail accompagné seulement de Cambodgiens, ce qui montre ce qu’on peut obtenir do ces hommes lorsqu’on ‑parle leur langue, qu’on connait leur caractère et qu’on sait les conduire. Il serait à désirer que nous eussions au Cambodge beaucoup d’hommes comme M. Pavie. (Nouveaux applaudissements.)

[“A few days after our arrival in Saigon, Messrs. de Chabanne and de Lacroix embarked for Cambodia and arrived at Phnom Penh mounted on elephants. From there, they went to Oudong and re-embarked to go down (or up) the river to the lakes. I must tell you in fact that what is called the arm of the lakes is one of the most extraordinary rivers that one can see: during a part of the year it flows in one direction, and during another part it flows in another, that is to say, it goes sometimes from Phnom Penh to the lakes and sometimes from the lakes to Phnom Penh. These gentlemen continued their exploration as far as Battambang and Angkor, the two provinces unfortunately Siamese, since Cambodia had ceded [!] these two beautiful parts of its territory to Siam, and they returned from there to Oudong to study there, based on numerous information gathered in the country, the possibility of founding an agricultural and industrial establishment, which was the principal aim of their journey.

At the same time, or rather a few days after the departure of MM. de Chabannes and Lacroix, M. de Llamby in turn left for Cambodia, but to make a completely different exploration there: he intended to first go up the great river, then to go down to Kampot and to visit especially the mountainous region which borders Kampot and which, probably, according to the indications of its configuration, is a mining region, but which has not yet been explored. Unfortunately, this interesting project was hampered by the great insurrection which began with the capture of the post of Sambor and which quickly spread throughout the country.

Meanwhile, Mr. Viscount d’Osmoy was studying in Saigon a project which could have brought to Cochinchina, according to his views, significant French capital, and added one more link to the rare commercial and industrial links which unite Cochinchina to France. But affairs in Cambodia were getting worse and worse, and my traveling companions were immobilized in Phnom Penh. However, they did not want to leave Cambodia and the French, still few in number, who had very cordially welcomed them in this country, at a time which seemed to be becoming very perilous, and they wrote to me at the beginning of February that their departure would seem to be a desertion and that they wished to continue their stay there.

Mr. de Chabannes and Mr. Lacroix, who had offered their services as officers to the colonel commanding in Cambodia, had even been able to take part in a reconnaissance and had fired a shot in the vicinity of Phnom Penh. Under these conditions, I went to join them. An insurrection was announced for the Chinese New Year, that is to say for February 15; but the band, having been dispersed a few kilometers from Phnom Penh, the country recovered its tranquility.

This holiday, which seemed so threatening, and when the insurrection was to break out, was a quiet day, during which I was able to take photographs of Cambodia that I will have the honor of showing you, at least some of them, because I was obliged to choose from those I had on hand, my collection not yet being at my disposal. But I must say before that that Cambodia seems to me of all our possessions in Indochina the country that can lend itself most immediately to colonization. It has extremely fertile lands where rich cultures have been attempted; The experience of the work of the Cambodians has also been made there and in a conclusive manner, by Mr. Pavie, who is attending this session, and to whom I am happy to be able to pay tribute here for the good he has accomplished in this country. Mr. Pavie courageously marked out Cambodia; it was he who planted all the stakes of the telegraph line that goes from Saigon to Bangkok across this country (Applause) and he accomplished this great work alone accompanied only by Cambodians, which shows what can be obtained from these men when one speaks their language, knows their character and knows how to lead them. It would be desirable for us to have many men like Mr. Pavie in Cambodia. (New applause.)] (p 17 – 8)

The screening of his own photographs gave the author the occasion to comment on Phnom Penh, starting with the too often harped upon “harem” of King Norodom:

Le roi du Cambodge, au moins quand j’étais à Phnom Pènh, avait d’autres soucis; il commande à trois cents femmes et cela né lui permet pas toujours de s’occuper des affaires politiques de son pays. (Nouvelle hilarité.)

AUTRE PROJECTION. — Voilà une grande rue de PhnomPènh. Phnom-Pènh n’a pas }lartout cette physionomie; mais j’ai voulu vous montrer une des rues qui a un aspect presque européen avec ses réverbères. Tous ces auvents de chaque côté sont le plus souvent garnis pendant le jour de joueurs de bakouang. La population de Phnom-Pènh est composée des races les plus diverses, de dix-huit races, je crois, et elle est très joueuse. La ferme des jeux doit donner dans ce pays-là des sommes assez rondes.

AUTRE PROJECTION. — Voilà encore une rue de Phnom Pènh qui est plus pittoresque que l’autre : la rue des Cocotiers ou des Bananiers avec un porteur de balances. Dans tout l’extrême Orient, Îcs indigènes portent ainsi leurs fardeaux aux deux extrémités d’un bambou couché sur l’épaule.

AUTRE PROJECTION. — Voilà à Phnom-Pènh le palais du roi avec de beaux morceaux d’architecture : cela rappelle — de loin — Versailles. Cette galerie, qui est très pittoresque, au contraire, est de style tout à fait cambodgien ou siamois : c’est la tribune royale des courses, — c’est de là que le roi assiste aux courses avec sa cour. Dans l’intérieur est une agglomération de constructions sans aucune harmonie, de l’architecture la plus différente et qui forment un ensemble des plus bizarres.

[The King of Cambodia, at least when I was in Phnom Penh, had other concerns; he commands three hundred women and that does not always allow him to take care of the political affairs of his country. (Laughter)

ANOTHER PROJECTION. — Here is a large street in Phnom Penh. Phnom Penh does not always have this physiognomy; but I wanted to show you one of the streets that has an almost European appearance with its street lamps. All these awnings on each side are most often filled during the day with bakouang players. The population of Phnom Penh is composed of the most diverse races, eighteen races, I believe, and it is very playful. The farm of games must give in this country quite round sums.

ANOTHER PROJECTION. — Here is another street in Phnom Penh that is more picturesque than the other: the street of the Coconuts or the Bananas, with a balance carrier. Throughout the Far East, natives carry their burdens on both ends of a bamboo lying on their shoulders.

ANOTHER PROJECTION. — Here in Phnom Penh is the king’s palace with beautiful pieces of architecture: it recalls — from a distance — Versailles. This gallery, which is very picturesque, on the contrary, is in a completely Cambodian or Siamese style: it is the royal grandstand for races, — it is from there that the king watches the races with his court. Inside is an agglomeration of buildings without any harmony, of the most different architecture and which form a most bizarre ensemble.”] (p 20)

From Phnom Penh, the author headed to Haiphong, and then Hanoi. He had reached French Indochina from Java, where he had led a naturalist and commercial prospection.

About the screened photographs

In 1888, the author gave his collection of photographs taken in Phnom Penh to the Paris Bibliotheque Nationale. While the rest of his photographic work — Java, Sumatra, Hanoi, Malaysia — is listed under his name at the French National Library, the Phnom Penh photos were indexed in a folder labeled “86 phot. de Ceylan, de Cochinchine, du Cambodge, du Tonkin, dont un portrait de Mgr Puginier, évêque du Tonkin, avec les Pères Bön et Landais, don X. Brau de Saint-Pol Lias, phot., en 1888.”

Main photo: The Royal baths in front of the Royal Palace, Phnom Penh, 1885, by the author (source:gallica.bnf.fr)

Tags: colonization, French Indochina, 1880s, Tonle Sap Lake, commerce, Chinese emigration, Royal Palace, Siam, Annam, Tonkin, Cochinchina, mining

About the Author

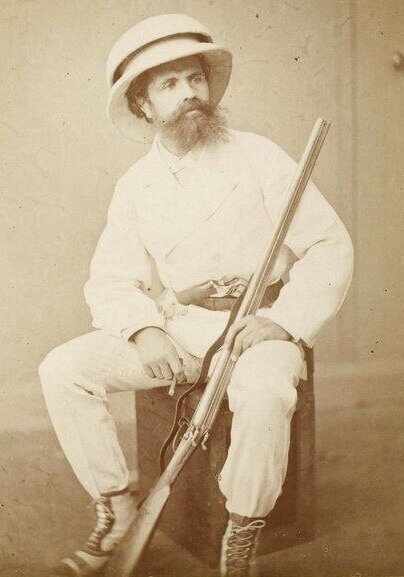

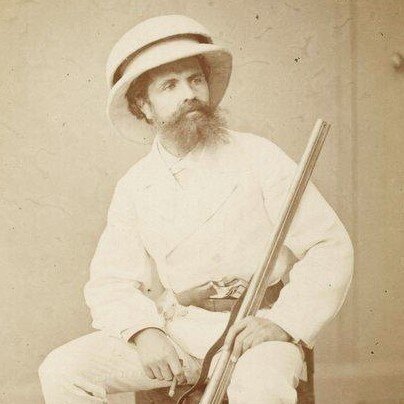

Xavier Brau de Saint-Pol Lias

Comte Xavier Brau de Saint-Pol Lias (4 July 1840, Seix (Ariège), France — 6 May 1914, Paris) was a French explorer, naturalist and travel writer who visited Java and Sumatra in 1876, then Tonkin, Cochinchina, Cambodia and Malaysia in 1884. He used to take photographs of the places he visited.

Born into an ancient aristocratic family from Southwestern France (Albigeois region), the Saint-Pol branch, he worked as a lawyer with the French National Bank from 1868 until 1873, before devoting himself to naturalist and commercial explorations in Southeast Asia. A staunch advocate of colonization, he founded the Société des études coloniales in 1873 and the Société des colons-explorateurs in 1875.

Brau de Saint Pol Lias took part in an exploratory commercial and geographical mission to Cochinchina and Cambodia in Oct 1884-February 1885, which he related in his October 1885 conference for the Société de géographie commerciale de Paris. He traveled with “valiant collaborators M. le vicomte de Chabannes, ancien lieutenant de vaisseau, M. de Llamby, ingénieur des mines, M. le vicomte d’Osmoy et M. Edouard de la Croix.” Explorer and travel writer Marcel Monnier also joined in.

He imported to France rare fauna and flora specimen, for instance Callula [Kaloula] pulchra, the banded bullfrog, and treated, dyed and dried sap of Toxicodendron vernicifluum or related trees used in Asian lacquerware. An exhibition at Musee du Trocadero in September-December 1885 showcased numerous artefacts brought back from Java, Sumatra and mainland Southeast Asia, including a Buddha statue claimed to have originated from Borobodur Temple.

Publications

- La Légion du génie et les camps retranchés: Le présent, l’avenir, le futur, Poitiers, 1870.

- Pérak et les Orangs Sakéys, Voyage dans l’intérieur de la presqu’île Malaise, Plon, Paris, 1883.

- De France à Sumatra par Java, Singapoor et Pinang: les anthropophages, Oudin, Paris, 1884.

- Chez les Atchés : Lohong, Plon, Paris, 1884.

- “Au Tonkin, en Cochinchine et au Cambodge”, Bulletin de la Société de géographie commerciale de Paris, Oct. 1885, vol 8.

- “Au Cambodge, feuillets détachés du journal d’un voyageur”, La Nouvelle revue, 1885; repub. as Phnom Penh, journal de voyage, Magellan, 2005 (Kindle Edition 2016), 69 p.

- La côte du poivre : voyage à Sumatra, Oudin, Paris, 1891.