Aspects socio-economiques du Laos medieval [Socioeconomic Aspects of Medieval Laos]

by Keo Manivanna

A "historical materialism"-based study on medieval Laos.

- Publication

- La Pensée, revue du rationalisme moderne, n. 138

- Published

- 1968

- Author

- Keo Manivanna

- Pages

- 16

- Language

- French

pdf 1.7 MB

This is the one and only published work by Laotian author Keo Manivanna, to our knowledge, in which we have found these relevant observations:

A State modeled after Angkor

“L’État Lao proprement dit apparut en 1366, quand un prince laotien Fa Ngum, exilé à Angkor à la suite de vicissitudes politiques, fit la conquête des Pays Lao, et fonda le Royaume de Lan Xang ou du million d’éléphants (traduction officielle, plus probablement: million de nagas). Sa capitale Xieng Dong — Xieng Thong, deviendra au xvie siècle Louang Prabang. Élevé à la cour khmère, il fait venir d’Angkor une mission culturelle qui introduit au Laos le bouddhisme theravàda, les arts khmers et les textes politico-religieux cambodgiens. Le modèle khmer, dont le centre est la cité, va ainsi se superposer à la structure thaï ancienne, fondée sur le village.

Pour étudier de façon satisfaisante l’apparition de l’État Lao, il faudrait connaître la société thaï d’avant la fondation du Lan Xang. Mais on est ici réduit aux hypothèses et aux analogies avec ce qu’on sait de la structure sociale actuelle des sociétés thaï non bouddhisées (celles du nord-ouest du Vietnam). Ces sociétés thaï sont caractérisées par des structures étatiques primitives, dominées par des minorités aris¬ tocratiques. Le chef suprême de la famille dirigeante, les cam (l’or), s’appelle Cao Phèn Cam. II est le médiateur entre la divinité et le reste de la société, donne au printemps le premier coup de pioche propitiatoire, reçoit un impôt en nature et en barres d’argent, a droit à des corvées. C’est-à-dire que le travail et les impôts destinés à la communauté se confondent avec le travail et les impôts destinés à l’individu personnifiant l’État et les forces vives de la communauté. Trois formes de propriété se juxtaposent : celle du Cao Phen Cam, celle des communautés rurales, celle de la famille. L’esclavage frappé tout chef de maison qui né paie pas l’impôt et perd ainsi son statut d’homme libre 2. Il peut être acheté par un particulier. Il s’agit donc d’une sanction, non de la base systématique de la production. La famille du Thaï tombé en esclavage peut d’ailleurs le racheter.

L’État Lao s’organise au xive siècle à partir du modèle khmer. Mais il faut d’emblée faire remarquer qu’il né s’agit pas de la société angko- rienne classique, fondée sur l’hindouisme, mais de la société angkorienne tardive, dans laquelle la religion dominante est devenue le bouddhisme. La conception du pouvoir royal, dès le début du Royaume Lao, est nourrie de traditions bouddhistes. Le roi est un médiateur vers la divi¬ nité, et cela d’autant plus qu’il bénéficie des mérites acquis pendant ses vies antérieures, en vertu de la doctrine de transmigration.

Sur le plan politique, le passage à l’État Lao est marqué par le contrôle d’une soixantaine d’ethnies, situées de part et d’autre du cours moyen du Mékong. On assiste à une mutation des pouvoirs par rapport à ceux de l’ancien chef thaï : le roi du Lan Xang porte le titre de Cao Sivit le (propriétaire des existences). Ce titre se traduit dans les conquêtes de Fa Ngum par des faits précis. Après avoir été évincés par Fa Ngum, les princes thaï n’eurent la vie sauve que parce qu’ils firent acte de soumission. En quelque sorte les princes thaï devinrent endettés de leur vie vis-à-vis du roi et, avec eux, tous leurs sujets. Les tributs et les corvées devinrent la dette des existences. Fa Ngum l’entendit ainsi. Il usa de représailles terribles contre les vassaux récalcitrants et les remplaça presque tous successivement par de nouveaux princes. Le roi est seul propriétaire. Dans le contexte du Lan Xang, il faut réviser le terme de thaï (homme libre). Né peuvent prétendre à ce titre que les nobles et la congrégation des moines bouddhistes, à qui le roi donne des terres (et tous les habitants qui les peuplent) en apanage. Cette minorité participe donc à la propriété royale.

Un autre titre du roi, Cao Fa Phèn Din (le propriétaire du ciel et de la terre), indique le caractère de monarque universel du roi et correspond fonctionnellement à une idée fondamentale du bouddhisme : par l’intermédiaire de la religion, tout individu libre (au sens de non-esclave) peut élever son statut social, car il existe des équivalences entre les titres laïques et les titres religieux. Plus l’individu se détache de l’existence, plus son statut social s’élève et plus il acquiert de mérites pour les exis¬ tences futures. En étant le protecteur officiel du bouddhisme, le roi assure donc les conditions d’existence et de délivrance de ses sujets. Il apparaît comme un médiateur quasi divin entre l’ordre sacré et l’ordre laïque.

Au niveau administratif, le passage à l’État Lao fut marqué par l’apparition d’un vice-roi, dans la tradition khmère, et d’un conseil des ministres formé par des princes. L’administration de l’Empire devait tenir compte de la structure physique, formée par une série de petites plaines et de plateaux morcelés par les rivières ou les montagnes. Le Mékong, lui-même, est entrecoupé par des rapides. Ce morcellement territorial aura deux conséquences opposées :

— D’une part, il favorise le maintien de la structure ethnique locale d’où, à travers l’histoire du Lan Xang, une tendance à l’autonomie des provinces qui né s’est jamais démentie. — D’autre part, il constitue un élément stratégique pour la défense du territoire national.”

[“The Lao State appeared in 1366, when a Laotian prince Fa Ngum, exiled to Angkor following political vicissitudes, conquered the Lao countries, and founded the Kingdom of Lan Xang or the million elephants (official translation , more likely: million naga). Its capital, Xieng Dong — Xieng Thong, became Louang Prabang in the 16th century. Raised at the Khmer court, he brought a cultural mission from Angkor which introduced Theravada Buddhism, Khmer arts and Cambodian politico-religious texts to Laos. The Khmer model, whose center is the city, will thus be superimposed on the ancient Thai structure, based on the village.

To satisfactorily study the emergence of the Lao State, one would need to know Thai society before the founding of Lan Xang. But here we are reduced to hypotheses and analogies with what we know about the current social structure of non-Buddhized Thai societies (those of northwest Vietnam). These Thai societies are characterized by primitive state structures, dominated by aristocratic minorities. The supreme head of the ruling family, the cam (gold), is called Cao Phèn Cam. He is the mediator between the divinity and the rest of society, gives the first propitiatory blow of the pickaxe in the spring, receives a tax in kind and in bars of silver, is entitled to corvées. That is to say, the work and taxes intended for the community are confused with the work and taxes intended for the individual personifying the State and the living forces of the community. Three forms of property are juxtaposed: that of Cao Phen Cam, that of rural communities, that of the family. Slavery affects any head of household who does not pay tax and thus loses his status as a free man. It can be purchased by an individual. It is therefore a sanction, not the systematic basis of production. The family of the Thai who fell into slavery can also buy him back [similar in Cambodia, ADB].

The Lao State was organized in the 14th century based on the Khmer model. But it must be noted from the outset that we are not talking about classic Angkorian society, founded on Hinduism, but about late Angkorian society, in which the dominant religion became Buddhism. The conception of royal power, from the beginning of the Lao Kingdom, was nourished by Buddhist traditions. The king is a mediator towards divinity, all the more so since he benefits from the merits acquired during his previous lives, by virtue of the doctrine of transmigration.

On the political level, the transition to the Lao State is marked by the control of around sixty ethnic groups, located on both sides of the middle course of the Mekong. We are witnessing a change in powers compared to those of the former Thai leader: the king of Lan Xang bears the title of Cao Sivit le (owner of existence). This title is reflected in Fa Ngum’s conquests by precise facts. After being ousted by Fa Ngum, the Thai princes only survived because they submitted. In a way, the Thai princes became indebted for their lives to the king and, with them, all their subjects. Tributes and corvées became the debt of existence. Fa Ngum heard it like this. He used terrible reprisals against the recalcitrant vassals and replaced almost all of them successively with new princes. The king is the sole owner. In the context of Lan Xang, the term Thai (free man) must be revised. Only the nobles and the congregation of Buddhist monks, to whom the king gives lands (and all the inhabitants who populate them) as an appanage, can claim this title. This minority therefore participates in royal property.

Another title of the king, Cao Fa Phèn Din (the owner of heaven and earth), indicates the universal monarch character of the king and functionally corresponds to a fundamental idea ofBuddhism: through religion, every free individual (in the sense of non-slave) can raise one’s social status, because there are equivalences between secular titles and religious titles. The more the individual detaches himself from existence, the more his social status rises and the more merits he acquires for future existences. By being the official protector of Buddhism, the king therefore ensures the conditions of existence and deliverance of his subjects. He appears as an almost divine mediator between sacred and secular order.

At the administrative level, the transition to the Lao State was marked by the appearance of a viceroy, in the Khmer tradition, and a council of ministers formed by princes. The administration of the Empire had to take into account the physical structure, formed by a series of small plains and plateaus broken up by rivers or mountains. The Mekong itself is intersected by rapids. This territorial fragmentation will have two opposing consequences: — On the one hand, it favors the maintenance of the local ethnic structure hence, throughout the history of Lan Xang, a tendency towards provincial autonomy which has never been denied. — On the other hand, it constitutes a strategic element for the defense of the national territory.”

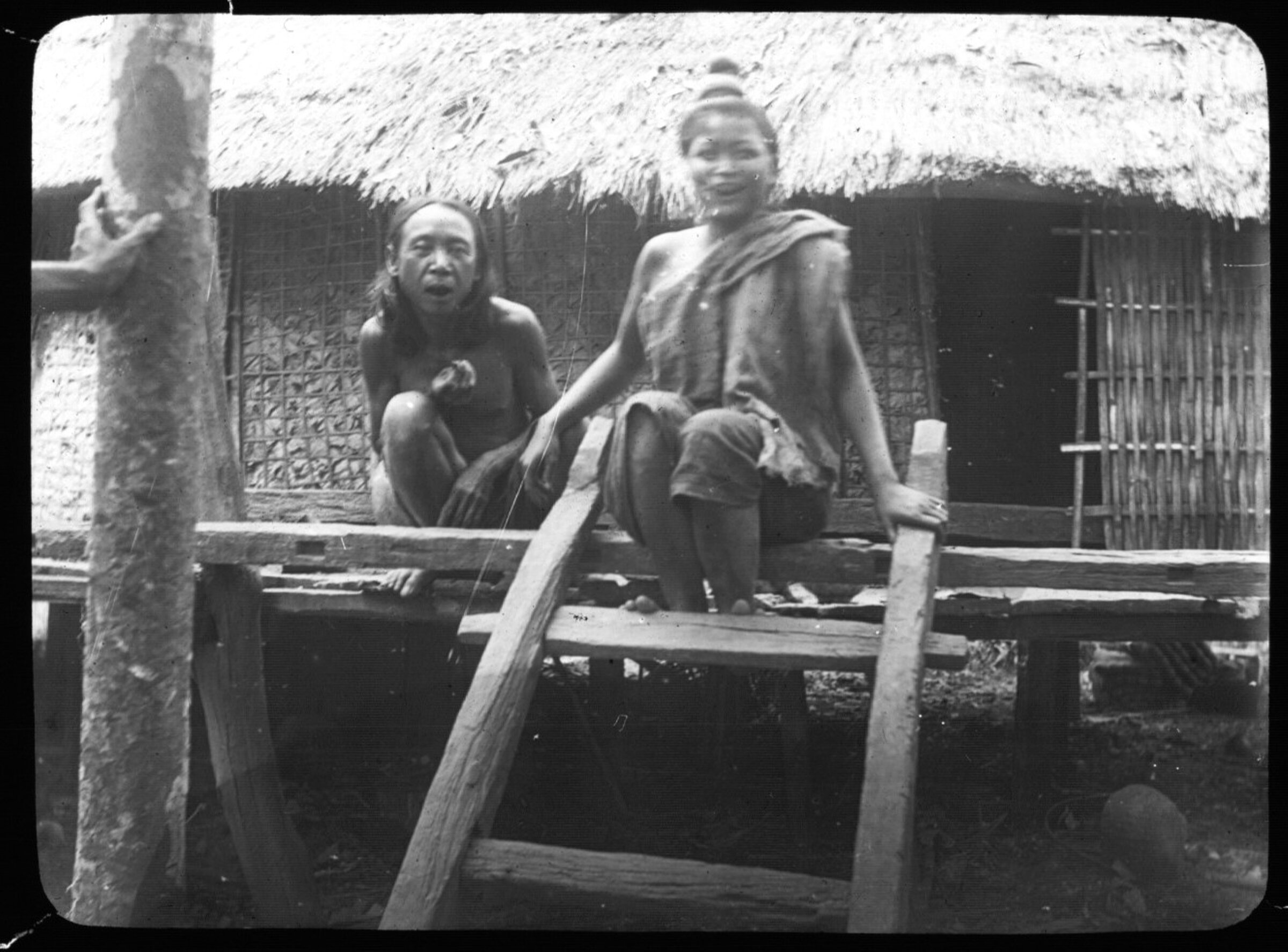

Family

“La famille lao est patrilinéaire et patrilocale. L’homme a le plus fort statut. C’est l’être des relations extérieures par excellence. Il fait les gros travaux dans les rizières ” et les rays. Il chasse et pêche également. L’homme, enfin, s’occupe du commerce. La femme, dépendante de l’homme d’une manière générale, est chargée de régir moralement et économiquement l’intérieur de la maison. Domaine, dans lequel l’homme s’ingère peu, ce qui confère à la femme un statut relativement élevé. Elle est la dépositaire de l’argent familial. Elle éduque les enfants et pourvoit à tous les besoins familiaux (alimentation, confection et teinture des vêtements, entretien, ravitaillement en eau, etc.). Pendant les travaux agraires, elle collabore avec l’homme : elle est spécialement chargée du repiquage, travail qui né demande pas d’efforts physiques importants, mais exige souplesse, rapidité et patience. À la fin de la saison des pluies, elle fait un jardin potager sur les rives des rivières, libérées par le retrait des eaux. Cette activité donne lieu, dans les villages proches des centres, à un petit commerce.”

[“The Lao family is patrilineal and patrilocal. The man has the highest status. He is the being of external relations par excellence. He does the heavy work in the rice fields” and the rays. He also hunts and fishes. Man, finally, takes care of business. The woman, dependent on the man in general, is responsible for morally and economically governing the interior of the house. Domain, in which the man interferes little, which gives the woman a relatively high status. She is the custodian of the family money. She educates the children and provides for all family needs (food, making and dyeing clothes, maintenance, water supply, etc.). During agrarian work, she collaborates with the man: she is specially responsible for transplanting, work which does not require significant physical effort, but requires flexibility, speed and patience. At the end of the rainy season, she makes a vegetable garden on the banks of the rivers, freed by the receding waters. This activity allows for small business activity in the villages close to the centers.”]

Commerce

“Le calendrier proto-indochinois prévoyait un jour d’interdit de travail tous les dix jours. C’est ce jour qu’ils choisissaient pour leurs échanges. Les produits importants (benjoin et sticklaque surtout) étaient généralement apportés au Phở lam, personnage semi officiel, souvent un commerçant de la plaine voisine, qui s’approvisionnait directement avec ses pirogues dans les centres ou auprès des marchands qui en venaient. Le Phở lam était choisi

par les Proto-indochinois pour la confiance qu’il inspirait (il parlait leur langue), et pour les services qu’il rendait auprès des autorités lao. A côté du Phở lam, les échanges étaient faits soit par des marchands de la campagne qui servaient d’intermédiaires, soit par de gros marchands urbains qui s’approvisionnaient directement dans l’arrière pays. Pour ce genre de commerce, souvent plusieurs marchands s’associaient et utilisaient jusqu’à quinze ou vingt hommes répartis sur plusieurs pirogues, dont certains étaient leurs esclaves et d’autres des employés. Le moyen de communicationle plus courant pour remonter les cours d’eau était la pirogue à perche. Lorsqu’ils arrivaient à destination, ils établissaient sur la berge un abri pour les produits apportés et ceux qui allaient être obtenus, puis ils sillonnaient les environs en quête de produits locaux. Pour descendre les marchandises vers les centres, en plus des pirogues, ils construisaient des radeaux. Arrivés en ville, le bambou qui avait servi à la construction des radeaux était vendu. Dans ce commerce, les Lao s’enrichissaientaux dépens des Proto-indochinois, qui par suite de dettes insolvables devenaient souvent leurs esclaves. Ce commerce né semblait pas taxé par l’Etat qui se contentait d’un impôt général annuel.”

[“The proto-Indochinese calendar provided for a day when work was prohibited every ten days. It was this day that they chose for their exchanges. Important products (especially benzoin and sticklaque) were generally brought to the Phở lam, a semi-public character, often a trader from the neighboring plain, who obtained supplies directly with his canoes in the centers or from the merchants who came from there. The Phở lam was chosen by the Proto-Indochinese for the trust he inspired (he spoke their language), and for the services he provided to the Lao authorities. Alongside the Phở lam, trade was carried out either by rural merchants who served as intermediaries, or by large urban merchants who obtained their supplies directly from the hinterland. For this type of trade, several merchants often joined forces and used up to fifteen or twenty men spread across several canoes, some of whom were their slaves and others their employees. The most common means of communication to go up the rivers was the pole canoe. When they arrived at their destination, they established a shelter on the bank for the products brought and those that were going to be obtained, then they traveled the surrounding area in search of local products. To bring the goods down to the centers, in addition to canoes, they built rafts. Arriving in town, the bamboo that had been used to build the rafts was sold. In this trade, the Lao enriched themselves at the expense of the Proto-Indochinese, who, as a result of insolvent debts, often became their slaves. This trade did not seem to be taxed by the State, which was content with a general annual tax.”

Asian Mode of Production

“Il nous semble que la catégorie de mode de production asiatique peut s’appliquer au Lan-Xang dans la mesure où :

1) l’économie repose encore sur des communautés rurales ; 2) il existe une forme d’Etat, où le roi est le médiateur des intérêts de la communauté et où les hommes libres sont soumis à des corvées et à des impôts qui sont à la fois rentes pour l’Etat et rentes pour l’aristocratie. La société du Lan-Xang est une société de classes où les rapports anciens, communautaires, survivent. Cette société de classes appartiendrait à une forme de mode de production asiatique sans grands travaux, avec la nuance que nous avons apportée relative aux canaux du XVIIe siècle. Mais l’apparition du mode de production asiatique et de l’Etat dans les tribus thaï se fit dans des conditions que l’Ethnologie et l’Histoire né permettent pas encore d’éclairer.”

[“It seems to us that the category of Asian mode of production can be applied to Lan-Xang to the extent that:

1) the economy still relies on rural communities; 2) there existed a form of State, where the king is the mediator of the interests of the community and where free men are subject to corvées and taxes which are both rents for the State and rents for the aristocracy. Lan-Xang society is a class society where old, community relationships survive. This class society would belong to a form of Asian mode of production without major works, with the nuance that we have brought relating to the canals of the 17th century. But the appearance of the Asian mode of production and of the State in the Thai tribes took place in conditions that Ethnology and History do not yet allow us to clarify.”]

Tags: Lao, Khmer Empire, proto-Indochinese, commerce, state formation, medieval Southeast Asia, "proto-Indochinese", Thai, family, Laotian women

About the Author

Keo Manivanna

Keo Manivanna is a Laotian historian. We’re looking for biographical information.