Early China and the Indian Ocean Networks

by Tansen Sen

Early China’s interactions with the maritime world and the eventual emergence of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) as a leading naval power in the 15th century.

- Publication

- in The Sea in The Ancient World, Philip de Souza and Pascal Arnaud eds., Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, pp 536-47.

- Published

- 2017

- Author

- Tansen Sen

- Pages

- 12

- Language

- English

pdf 623.3 KB

This insightful study of ancient Chinese maritime routes is focused on the Indian subcontinent, which might explain the relatively scarce notations related to mainland Southeast Asia. However, the following observations seem important for researchers in pre-Angkorean and Angkorean history:

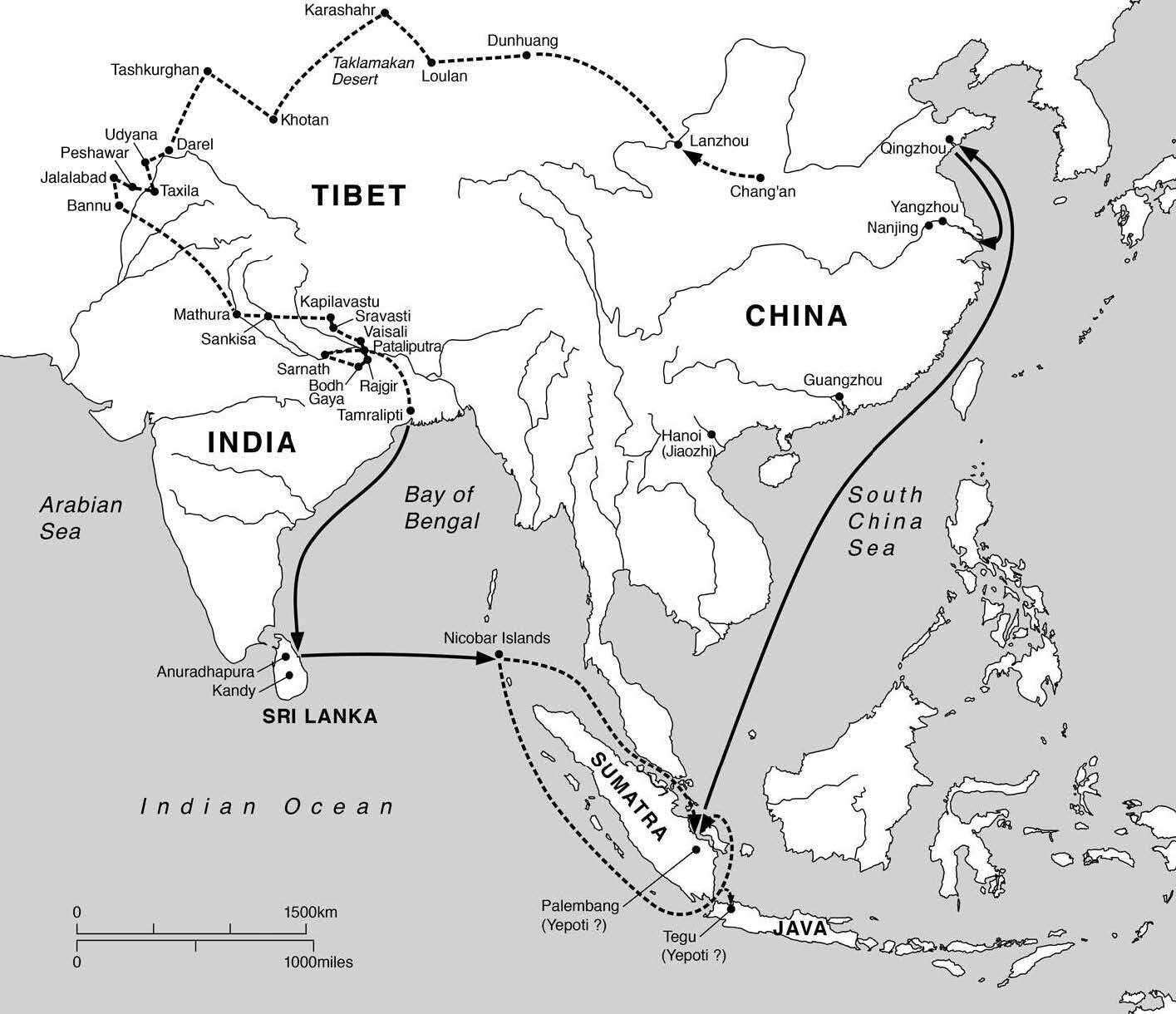

- By the third century AD, Jiaozhi [Hanoi] had emerged as a key center for Buddhist activities. The port attracted foreign traders from South and Central Asia, some of whom are known to have practiced Buddhism. Frequently cited is the example of the Sogdian monk Kang Senghui (d. 280 AD), whose ancestors lived in India before his father migrated to Jiaozhi. It is not clear if Kang became a monk in Jiaozhi, which would indicate the presence of monastic institutions in the region, but the site was evidently an important link between Buddhist centers in South Asia and China. In fact, from Jiaozhi, Kang Senghui travelled to Jiankang (present-day Nanjing), the capital of the Wu polity, where the ruler Sun Quan (r. 222 – 252) was actively promoting Buddhism and maritime trade. Not far from Jiankang, in the northern coastal region of the Jiangsu province, is Mount Kongwang, where some of the earliest images associated with Buddhism have been found engraved on the boulders. Dating from the late-second or early third century, these images suggest the existence of Indo-Scythian or Parthian seafaring communities in the region.”

- “Existing textual sources suggest that Faxian (1) was the first Chinese monk to travel from South Asia to China by the maritime route. Faxian, who embarked on his trip through the overland route in 399, started his return voyage by first travelling on a mercantile ship from the eastern Indian port city of Tamralipti to Sri Lanka in 411. Subsequently, he took a ‘large ship’ from Sri Lanka that was sailing towards Southeast Asia. After reaching ‘Yepoti’ (either Sumatra or Java), the Chinese monk transferred to another large mercantile ship that was meant to travel to Guangzhou, but because of a storm ended up instead in Shandong province in northeast China.”

Faxian’s land and maritime routes, 5h century (map by Tansen Sen)

- “Already in the third century, the above-mentioned Wu polity had tried to establish diplomatic, and perhaps commercial, ties with rulers in Southeast Asia. At that time, the Funan polity controlled several ports in the Malay Peninsula, especially Oc Eo, which seems to have been the main maritime link between coastal China and the Indian Ocean.21 Bactrian horses, Roman glassware, and South Asian precious and semi-precious stones entered the Chinese coast through these Funanese-controlled ports. It was perhaps to access foreign commodities directly from the Funan ports that the Wu court sent envoys, named Kang Tai and Zhu Ying, to visit the region in the mid-third century. The envoys returned with detailed information about Funan as well as the Southeast Asian polity’s connections to South Asia.”

- “China’s interactions with the maritime world between the seventh and ninth centuries set the stage for the eventual emergence of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) as a leading naval power in the early fifteenth century. While the Song court established fiscal policies and administrative structures to profit from maritime trade, Chinese private traders during the eleventh and twelfth centuries started venturing into South and Southeast Asian ports to procure foreign goods. This active involvement of the court and private traders in maritime trade resulted in the improvement of shipbuilding technology and navigational skills. The Yuan court, under Qubilai Khan, employed these advances to launch the first naval attacks on polities beyond the Chinese coastal region. The court’s interest in the Indian Ocean world peaked during the reign of the Ming emperor Yongle (r. 1402 – 1424), who initiated the unprecedented maritime expeditions between 1405 and 1433 that reached the Swahili coast of Africa.”

(1) Faxian 發現 (337, Linfen, China – 422, Jingzhou, China), also known Fa-Hien, Fa-hsien and Sehi, was a Chinese Buddhist monk and translator who traveled by foot from China to India to acquire Buddhist texts. He was already about 60 years old when he started his journey, visiting sacred Buddhist sites in Central, South and Southeast Asia between 399 and 412 CE, of which 10 years were spent in India. He described his journey in his travelogue, A Record of Buddhist Kingdoms (Foguo Ji 佛國記). His memoirs are a notable independent record of early Buddhism in India. He took with him a large number of Sanskrit texts, whose translations influenced East Asian Buddhism. [from Wikipedia]

Further reading: CHEN Jiarong 陈佳荣著 (also Aaron Chen, Chan Kai Wing), Sui qian Nanhai jiaotong shiliao yanjiu 隋前南海交通史料研究 [A Study on the Historical Materials of Transportation in the South China Sea before the Sui Dynasty], Hong Kong: Center of Asian Studies, The University of Hong Kong (2003).

Photo: A statue of monk Faxian at the Maritime Museum and Aquarium of Singapore.

Tags: Buddhism, Buddhist travelers, India, China, Yangzhou, maritime routes, Early Southeast Asia, Ming dynasty, sea, Sumatra, Srivijaya, Funan, Oc Eo

About the Author

Tansen Sen

Tansen Sen is the Director of the Center for Global Asia, NYU Shanghai, and a Global Network Professor with NYU (New York University, USA), specializing in Asian history and religions, India-China interactions, Indian Ocean connections, and Buddhism.

He is the author of Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600‑1400 (2003; 2016) and India, China, and the World: A Connected History (2017). He has co-authored (with Victor H. Mair) Traditional China in Asian and World History (2012) and edited Buddhism Across Asia: Networks of Material, Cultural and Intellectual Exchange (2014). He is currently working on a book about Zheng He’s maritime expeditions in the early fifteenth century and co-editing (with Engseng Ho) the Cambridge History of the Indian Ocean, volume 1.

A Professor of History at Baruch College, City University of New York, Tansen Sen has done extensive research in India, China, Japan, and Singapore, and was the founding head of the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Center in Singapore.

Read the author’s ‘Journey Between Two Nations’.