If Khmer religious ‘syncretism’ has been widely studied, the author develops here quite a novel approach, stating that in 12th-century Angkor ‘sections of Jayavarman’s Buddhist temples were reserved for Saiva and Vaisnava rites, but within a Buddhist framework or mandala.’

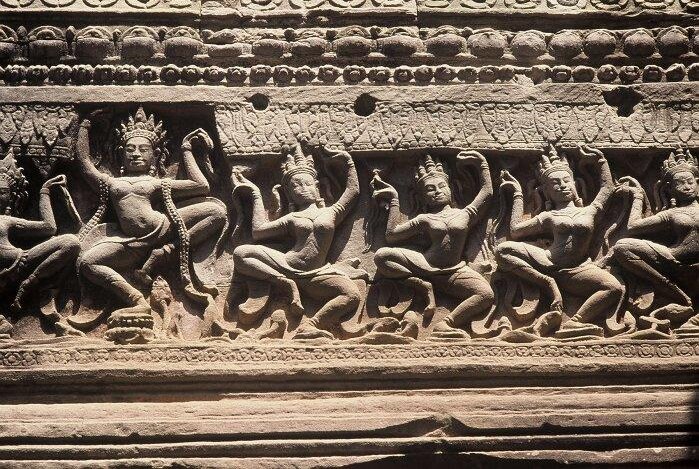

The development about the structures called by the French archaeologists ‘Salle aux danseuses’ (Hall of Dancers) is particularly interesting. According to the author, these ‘new halls could have accommodated several dozen people at a time in each of Preah Khan, Ta Prohm, Banteay Kdei, Banteay Chmar temples, and if the Bayon was involved that could have accommodated hundreds, so the new cult symbolised by the dancers could have engaged large numbers of people in temple rites. If the ceremonies in Angkor were cyclical and repeated, it would be a reasonable assumption that, for example, the adults among the 14,000 residents of Preah Khan would have been involved, over time, but not the 208,532 villagers who supported the temple complex.’

The author also notes a change in the composure of celestial dancers in sculptures and bas-reliefs in these ‘dance halls’: ‘The Bayon too shares the motif of dancing goddesses — of the size of those in Banteay Chmar, but in far greater numbers. The demeanour of the Bayon dancers, whose bodies are braced and whose challenging eyes, with one foot raised to the opposite thigh in an extreme dance movement, suggests they are akin to the yogini that whirl around the supreme dancing deity Hevajra in the late Bayon style bronzes. The emphatic use of the motif of dancing goddesses on the Bayon is unprecedented in Angkor, and yet it is what might be anticipated in a cult of Hevajra…’

As the author concludes: ‘The ruins of Ta Prohm, today still partly overgrown with the trees of the forest that once engulfed it when the Khmers moved their capital south, seem to hold clues to a seminal message from the Buddhist king who apparently sought large-scale participation in rituals in his temples to consolidate and legitimise his Buddhist state. For only this level of engagement could have ended and absorbed the Saiva state that first unified the Khmers in the ninth century and enabled them to eventually build one of the great Asian empires. Vajrapani’s ‘killing’ Siva then reviving him in the Buddhist mandala, in the classic dompteur-dompté metaphor of transformation, re-enacted in the mature Vajrayana by Hevajra, reached its political dénouement in Jayavarman VII’s royal strategy to transform the Saiva state and implant Buddhism definitively among the Khmers.’