La fete des eaux a Phnom Penh (1901) [Phnom Penh Water Festival, 1901]

by Adhémard Leclère

Exploring the origins and meanings of one of the most typically Cambodian festival, ពិធីបុណ្យអុំទូក, Water Festival (as witnessed in 1901).

- Publication

- BEFEO t. 4, 1904, pp. 120- 130.

- Published

- 1904

- Author

- Adhémard Leclère

- Pages

- 10

- DOI

- https://doi.org/10.3406/befeo.1904.1298

- Language

- French

pdf 910.0 KB

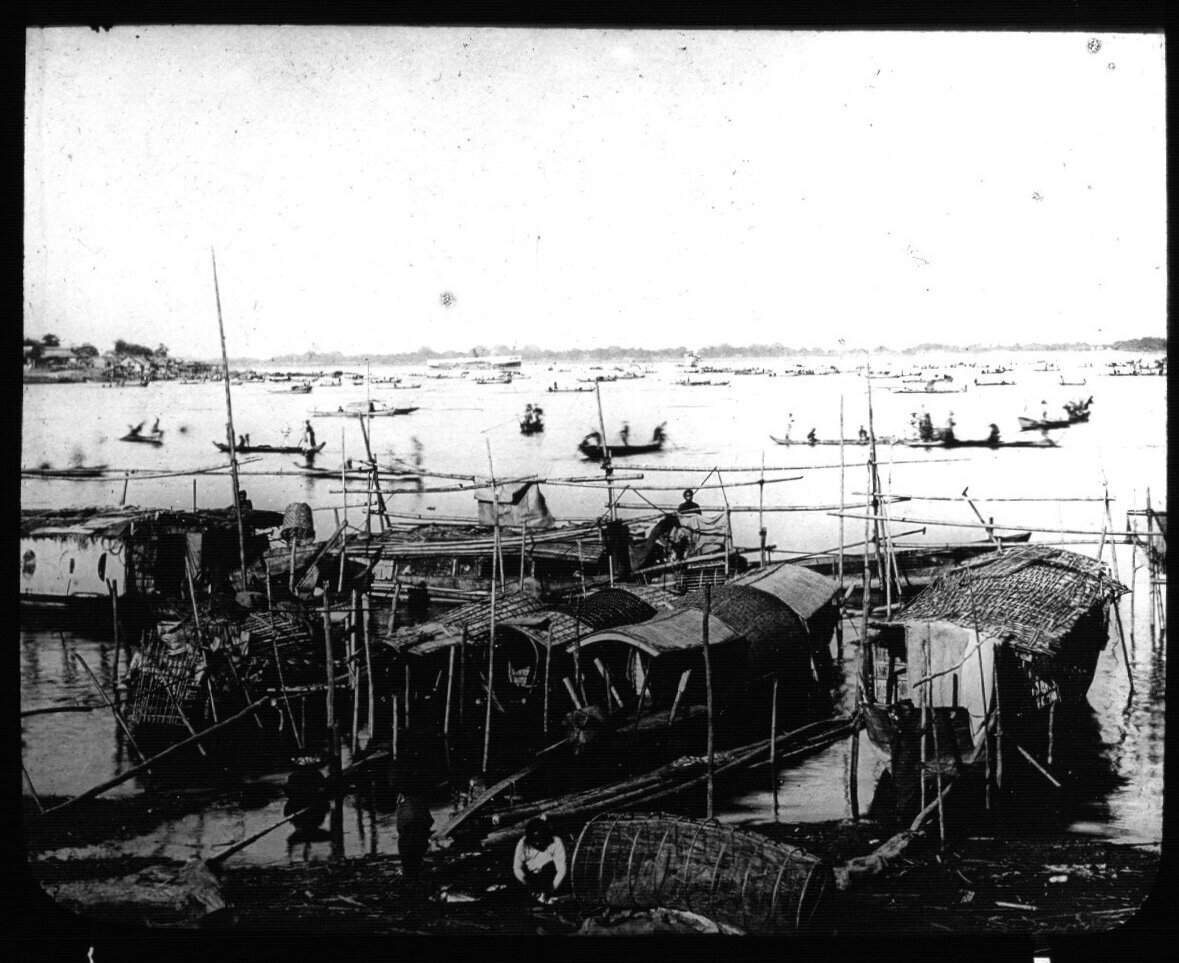

Khmer Water Festival បុណ្យអុំទូក Bön Om Tuk — អុំ [om] being often interpreted as “water” or “great” when this verb means literally “speeding the boat with the same gesture as grasping the stalks or rice with both hands” , paddling — is an important festival in the Cambodian calendar, and yet the origin of the boat races and related ceremonies remains wrapped in mystery.

Recently, the joyous festival has been tinged with national references. The official website of Cambodia’s Tourism Bureau states that it is “the celebration of the victory of Jayavarman VII over the Cham [invaders], yet also the reversal of the Tonle Sap course at the end of the rainy season.” One sure fact: it occurs during three days from the 14th “Keit” (waxing moon period) day of the month of Kadhek ខែកត្តិក, equivalent in Khmer lunar calendar to the Indian month Kārtika sk कार्त्तिक.

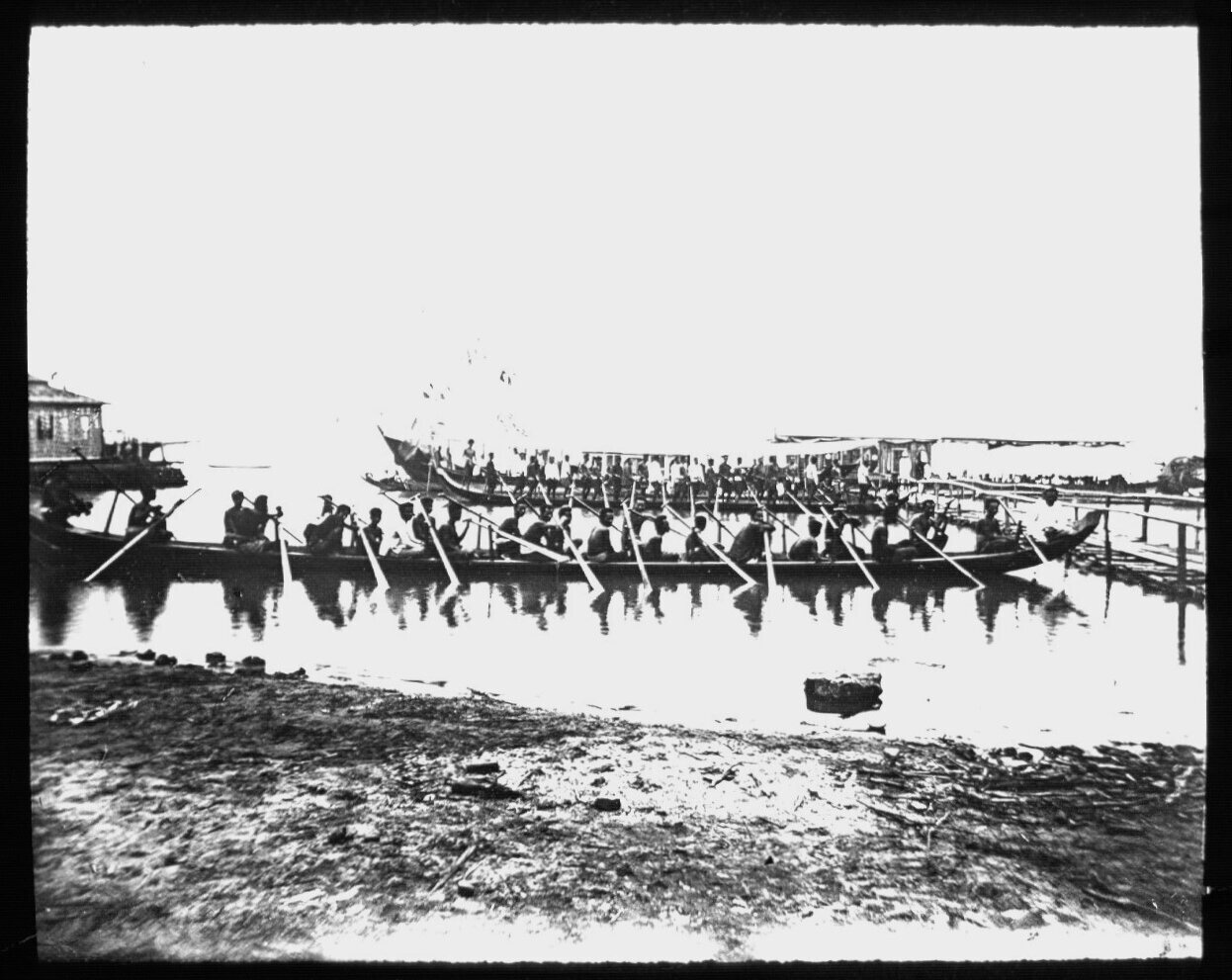

The number of boats powered by 80 men or women entering the races has varied from 100 to 500 in Phnom Penh — the only place for this event until the last decades, since it has been linked to royal power over the elements -, less in Siem Reap and other provinces. In typical Khmer way, these races are combined with other celebrations such as the Salute to the Moon and its Bodhisattva Rabbit [សូមគោរពព្រះច័ន្ទ Som koroop Preah Chan] , the floating lanterns, the Ok Ombok អកអំបុក [rice chucking ceremony], the cutting [and hanging] of the sacred cord symbolically liberating the nagas from the flooded lands, the ritual of catching the kite ការចាប់កូនខ្លែង, to form a truly unique version of what is called Mid-Season Festival in other cultures, or the Ganga puja in India, with two common referees in the human saga: moon and water.

Taking part in the 1901 celebrations in Phnom Penh, the author, a curious mind and precise researcher who worked as head of the French civil administration in Cambodia, wanted to learn more about this “part Brahmanic, part Buddhist, entirely Cambodian” festival. Here are some of his remarks:

- Les treizième, quatorzième et quinzième jours de la lune croissante du mois d’Àsôc, qui correspondent aux 25, 26 et 27 octobre 1901, fut célébrée à Phnom-Penh la fête que les Européens désignent sous le nom de « fête des eaux » et que les Cambodgiens nomment thvo bon pranah tuk no, « fête de la joute des pirogues [à poupe et à proue] redressées en pointe », ou thvo bon loi pratip, « fête des feux flottanls ». Cette fête dure trois jours. Le dernier, qui correspond chaque année au jour de la pleine lune d’Asoc (pâli Assayuja), ferme la saison du vossa (pâli vassa), des pluies, ou de la retraite des religieux, et ouvre la période de trente jours pendant laquelle a successivement lieu, dans tous les monastères, la fête de la distribution des vêtements à ces mêmes religieux (thvo bon kathën, pâli kathina).

[On the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth days of the waxing moon of the month of Asoc, which correspond to October 25, 26 and 27, 1901, the festival that Europeans call “water festival” and that Cambodians call thvo bon pranah tuk no, “festival of the jousting of canoes with tips [stern and bow] upturned”, or thvo bon loi pratip, “festival of floating fires” was celebrated in Phnom Penh. This festival lasts three days. The last, which corresponds each year to the day of the full moon of Asoc (pali Assayuja), closes the season of vossa (pali vassa), of the rains, or of the retreat of the religious, and opens the period of thirty days during which takes place successively, in all the monasteries, the festival of the distribution of clothes to these same religious (thvo bon kathen, pâli kathina). [ADB Input: បុណ្យប្រណាំងទូកង bon pranang tuk no, festival of the joust of the boats with turned-up tips, is no longer used to name the festival, while ពិធីបណ្ដែតប្រទីប pithi bandetabratib, celebration of the floating lanterns, is now in use. The author notes that in Siam this ritual is called sât loi kâthông, with candles set on carved leaves, but nowadays the use of leaves instead of paper is frowned upon by strict keepers of Cambodian traditions. However, the author [p 130] carefully noted that while dignitaries were putting afloat loi pratip, large paper illuminations, “the common people used to send onto the river thousands of loi kanton made of banana leaves or trunks.”]

- Describing the initial parade of dugouts in front of the royal floating house before the races, the author notes with delight the cheekiness of the “buffoons” heating up the stamina of the oarsmen and paddlers:

Elles passent, toutes ces pirogues, une à une, à quarante mètres environ des jonques royales, lentement ; les unes montées par des rameurs debout, les autres par des pagayeurs assis, d’autres encore par des rameurs assis à l’avant et debout à l’arrière, quelquefois au nombre de quarante ; et la foule rit des grimaces des bouffons, des poses bizarres qu’ils prennent, des grivoiseries qu’ils jettent à la face du roi, des dames cambogiennes, des Français quelquefois: “Vos femmes sont belles, ô Français, leur teint est blanc, et c’est beau; mais leur nez est long, et celui de nos femmes, moins belles, est court./ О femmes, vous avez ce qu’il faut pour la joie de vos époux, né l’avez-vous pas pour la mienne?/ Il a plu beaucoup cette année, le fleuve a débordé ; il y aura beaucoup de riz et de joie. /Toutes les femmes seront grosses du fait de leurs maris ou du fait de leurs amants. Peu importe !/ Au temps de Chaufa Bèn on avait dix tilles pour une barre d’argent et cinq veuves pour

une demi-barre; maintenant il faut cinq barres pour avoir une fille et les veuves ont autant de prétentions que les filles./ Nous portons des sampots et les Français portent des pantalons comme les Chinois, mais nous portons les cheveux comme les Français et les Françaises les portent comme les Annamites./ Les Cambodgiennes sont amoureuses toute la nuit, les Annamites sont amoureuses toute la journée. On dit que ies Françaises né sont amoureuses que dans la soirée./ О filles, retirez vos sampots, afin que je voie celle d’entre vous qui me plaît le mieux! / Je suis laid, j’ai le pied bot, j’ai avalé mes dents, et les abeilles viennent déposer leur cire à l’angle de mes yeux; mes cheveux sont crépus et mes narines sont noires et sales comme la bouche des femmes annamites. Cependant il y a cinq belles et jeunes dames qui se disputent mes faveurs./ Les chiens se saluent en se reniflant au xxx, les Français en se donnant la main, et nous baisons nos épouses en les reniflant au visage ou au sein cela dépend de l’heure./О femme, je né sais pas ce que j’ai depuis six mois ; ça me fait chaud dans la poitrine quand je vous vois, et je pleure la nuit quand je né vous vois plus./ О femmes, vous êtes rusées, mais je suis amoureux; — vous me prendrez tout mon argent, mais je vous prendrai pour épouses et vous ferez cuire le riz de votre mari ; — vous êtes rusées, mais vous deviendrez grosses et vous allaiterez mes enfants ; — vous êtes rusées, mais je serai le maître de maison et vous serez mes servantes ; — vous êtes rusées, mais vous m’aimerez et je vous battrai ; — vous êtes rusées, vous êtes très rusées et pour vous venger de moi vous me ferez cornette.” Et les pirogues défilent et le roi sourit; les femmes rient à gorge déployée, et c’est une joie quand l’un des bouffons grimaçants lance une grivoiserie bien tournée.

“They pass, all these pirogues, one by one, about forty meters from the royal junks, slowly; some manned by standing rowers, others by seated paddlers, still others by rowers seated at the front and standing at the back, sometimes forty in number; and the crowd laughs at the grimaces of the jesters, the bizarre poses they take, the bawdiness they throw in the face of the king, the Cambodian ladies, the French sometimes: “Your women are beautiful, oh Frenchmen, their complexion is white, and it is beautiful; but their noses are long, and that of our women, less beautiful, is short./ O women, you have what is needed for the joy of your husbands, do you not have it for mine?/ It has rained a lot this year, the river has overflowed; there will be a lot of rice and joy./ All the women will be pregnant because of their husbands or because of their lovers. It does not matter!/ In the time of Chaufa Bèn there were ten girls for a bar of silver and five widows for half a bar; now it takes five bars to have a girl and widows have as many pretensions as girls./ We wear sampots and the French wear trousers like the Chinese, but we wear our hair like the French and the French women wear it like the Annamites./ Cambodian women are in love all night, Annamite women are in love all day. They say that French women are in love only in the evening./ O girls, take off your sampots, so that I can see which one of you pleases me best! / I am ugly, I have a club foot, I have swallowed my teeth, and the bees come to deposit their wax at the corner of my eyes; my hair is frizzy and my nostrils are black and dirty like the mouths of Annamite women. However, there are five beautiful young ladies who are competing for my favors./ Dogs greet each other by sniffing each other at the xxx, the French by shaking hands, and we kiss our wives by sniffing their faces or breasts, depending on the time of day./ O woman, I don’t know what’s wrong with me for six months; It warms my chest when I see you, and I cry at night when I don’t see you./ “O women, you are cunning, but I am in love; — you will take all my money, but I will take you for wives and you will cook your husband’s rice; — you are cunning, but you will become pregnant and suckle my children; — you are cunning, but I will be the master of the house and you will be my servants; — you are cunning, but you will love me and I will beat you; — you are cunning, you are very cunning and to get revenge on me you will make me a cornet.” And the canoes parade and the king smiles; the women laugh heartily, and it is all merriment when one of the grimacing jesters launches a well-turned bawdy joke.” [p 123 – 4]

- The author stressed the role played in the Water Festival ceremonies by the “purohita or bakou”, the keepers of Ancient Khmer royal rites and traditions, descendants of the oldest Brahmin families in the kingdom. They are in charge of bringing out of the Royal Palace the sacred sword, to keep the most sacred offerings of the festival in the Prah Ho, “the pavilion just right to the iron house” — the latter being the structure that has been erroneously called “Napoleon Pavilion” for decades. He even gives the name of the chief bakou (“Le bakou actuellement en fonctions est, en ce moment et depuis douze ans déjà, un nommé Kèv (prononcez Kêo)” [“The Baku currently in office is, at the moment and for twelve years now, a man named Kèv (pronounced Kêo)”] [p 126], and [with caution] concludes:

“Le fait que la ceremonie est présidée par un bakou ou prahm (bràhmana), par celui qui est chargé de la garde des quatre lances sacrées, à l’exclusion des religieux du Buddha, semble indiquer que son origine est brahmanique. Le fait que trois des cinq soi-disant ksatriyas évoqués sontVisnu, Çiva, Ganeça, et que l’invocation du prohm čei s’adresse aux déesses Dharani et Gangà confirme cette hypothèse.”

[“The fact that the ceremony is presided over by a baku or prahm (bràhmana), by the one who is charged with the guard of the four sacred lances, to the exclusion of the monks of the Buddha, seems to indicate that its origin is Brahmanic. The fact that three of the five so-called ksatriyas mentioned are Visnu, Çiva, Ganeça, and that the invocation of the prohm čei is addressed to the goddesses Dharani and Gangà confirms this hypothesis.” [p 128] [ADB input: yet the sacralization of land and water combined pertains to the most remote past of local cultures, including the Khmer one. នាមព្រះធរណី Neam Preah Thorni and នាមព្រះគង្គារ Neam Preah Kongkea, the Khmer equivalent of Indian goddesses Dharani and Ganga, symbolize beliefs that cannot be limited to Brahmanic influences.]

- In 1901, the ritual of “cutting the sacred strap”, and later to hang their tips on a sacred tree near the river, also incumbed to the Bakou. At the time, this “sturdy rope” — a buffalo leather strap, the author specified in another publication, Histoire du Cambodge (1916) — was stretched across the Tonle Sap, and its cutting symbolized the release of the river flow to the sea. ពិធីកាត់ខ្សែរព្រ័ត្យ phiti kat khsae prat remains an important part of the ceremony nowadays, but its meaning and the way it is performed have evolved: the King himself cuts a rope linking all boats taking part in the race.

- And the next part of this ritual, [ពាក់ព្រះព្រ័ត្រ peak prah prat], the hanging of the severed rope on a sacred tree, which is not mentioned in modern descriptions of the festival, was still highly valued in 1901, probably for the connection to past kings of Cambodia:

Pendant ce temps, les bakous détachent les deux tronçons (côn) de la sainte courroie (práh prat), en font un paquet qu’ils enveloppent dans un morceau de cotonnade blanche toute neuve qui leur a été donnée le matin, et l’emportent dans la province de Ponhéa-lu, à Phum Péak-Prat, ou “village de la courroie suspendue”. Là, elle est suspendue aux branches d’un arbre qui abrite un petit autel voué au génie de l’endroit, le Nak Ta Dankôm. Je n’ai pu savoir pourquoi la sainte courroie est déposée en cet endroit, mais on m’a affirmé, et je le crois, que ce lieu a été choisi lors de la création d’Oudong, après la prise et la destruction de Lovêk par les Siamois, en 1583. Avant cette date, le dépôt des bouts de la sainte courroie avait lieu près de Lovêk, à un village qui portait le même nom que celui qui le reçoit aujourd’hui : Phum Péak-Prat. Antérieurement à la fondation de Lovêk, le dépôt aurait eu lieu aux environs de la grande capitale d’Entipath qu’on nomme aujourd’hui Angkor-Thom.

[Meanwhile, the Baku detach the two sections (côn) of the holy belt (práh prat), make a bundle of it which they wrap in a piece of brand new white cotton which was given to them in the morning, and take it to the province of Ponhéa-lu, to Phum Péak-Prat [ភូមិពាក់ព្រ័ត] , or “village of the suspended strap”. There, it is suspended from the branches of a tree which shelters a small altar dedicated to the spirit of the place, the Nak Ta Dankôm. I have not been able to find out why the holy belt is deposited in this place, but I have been told, and I believe it, that this place was chosen at the time of the creation of Oudong, after the capture and destruction of Lovêk by the Siamese, in 1583. Before this date, the deposit of the ends of the holy belt took place near Lovêk, in a village which bore the same name as the one which receives it today: Phum Péak-Prat. Before the foundation of Lovêk, the deposit would have taken place in the vicinity of the great capital of Entipath which is today called Angkor-Thom.”] [p 130]

[ADB Input: we see here the attempt of linking modern Cambodia to its troubled past. In his Histoire du Cambodge, the author will dig out from the royal chronicles that King Preah Outey Soryapor, whose reign would bring calamities upon his country, in 1773 established his capital not far from Oudong, along a river called ព្រែកមាត់កណ្ដុរ Prek moat kandau or ព្រែកពាក់ព្រ័ត Prek Peak Proat, before moving hurriedly to Koh Chen under the pressure of Siamese and Viernamese armies. We are researching the possible location of this spot, noting that the “Dankom” mentioned by the author might be Wat Dangtong វត្តដងទង់. But there is also a mention of a Prek Peak Prat in the island of Chroy Changvar, much closer to Phnom Penh, which came to be called Prek Mean Leap, and subsisted in today’s toponymy as Prek Leap ព្រែកលៀប. | Similarly, the origin of the bandetabratib ritual is attributed to Barom Reachea II (Paramarājā II, Cau Bañā Cand, r. 1516 – 1566) who, after winning the war against King Kan at Banteay Chaktomuk in 1522, wanted to thank the Goddess Ganga ‑Mekong and apologize for the disturbance he had caused to nature.]

“Dancer on the prow”: Khmer codes

In 1901, the author did not pay attention to the hull decorations, nor to the specific roles of crew members on these huge yet elegant crafts. What he (and Francis Garnier, see below) called “buffoons” were probably the “activity leaders” [for lack of a better word] sitting at the prow of each boat. These អ្នករាំក្បាលទូក anak robam kbal tuk, “dancers at the prow”, are in fact channeling the protecting spirit of the boat, ជំនាងទូក cham neang tuk, in order to inspire and stimulate oarsmen or oarswomen. In effect, the boat is a living “naga”, with painted eyes watching the river.

The spiritual power of dance here meets the physical strain of race boating in the person of the “maiden dancing at the head of the boat”, នារីរាំក្បាលទូក neary robam kbal tuk, a tradition credited to King Srei Chetta for a boat race held in Toul Basan, Kompong Cham province, in 1516, and followed in modern days.

See a comment on “boat dancers” by Dr. Chen Chanrathana (in Khmer)

Introduction to the 1904 study in Fetes civiles et religieuses du Cambodge, 1916

This republication of the BEFEO text appeared in Cambodge: Fetes civiles et religieuses, Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1916, chap 12 [and chap 13 for Ok Ombok and Sampeah Preah Chan rituals]. Interestingly, the author compared the water-related ceremonies of Cambodia to those of Egypt. The book was dedicated “Au peuple cambodgien, qui est un bon peuple et qui fut jadis une grande nation, je dedie ce livre ou je le raconte comme je l’ai vu a tous les instants de sa vie.” [“To the Cambodian people, fine people which used to be a great nation, I dedicate this book where I recall them such as I have seen them in each and every moment of their lives.”]:

Tout d’abord il faut observer que la fête des eaux est vraiment la fête du retrait des eaux qui ont recouvert le sol pendant six mois, qui ont l’ont fécondé d’un apport d’humus, descendu des parties plus élevées et charrié par le Mékong, la «mère des eaux», ou Ganga. Elle rappelle celle que les Egyptiens célébraient quand, aux environs de l’équinoxe d’automne, les eaux du Nil (septembre) [La longueur du Nil est d’environ 7000 kilomètres, celle du Mekon est de 4500 kilomètres: sa largeur varie beaucoup : elle est de 1500 mètres à la hauteur de Kratie et de 1000 à Phnom Penh] commençaient à baisser, ce qui permettait aux cultivateurs de labourer la terre et de l’ensemencer. Au Cambodge, les eaux du fleuve commencent à monter en juin, croissent jusqu’en octobre. Elles atteignent parfois 16 mètres à Kratie, seulement 9 mètres à Phnom Penh et d’autant moins qu’elles sont plus près de la mer. Le Grand-Lac, ou Tonlé-Sàp, qui commence à croître en novembre, monte de 3 et 4 mètres, déborde sur les plaines jusqu’à 30 kilomètres par les rivières qui reçoivent aussi les eaux des pluies devenues abondantes et parviennent jusqu’à quelques kilomètres d’Ankorthom, la vieille el antique capitale des khmers doeum ou “du passé”. La montée des eaux dure donc environ cinq mois et la descente plus de sept mois. C’est en octobre, alors que les eaux d’inondation commencent à découvrir les terres, qu’on célèbre, comme en Egypte, la fête de la baisse des eaux que je vais décrire ici.

[“First of all, it must be noted that the water festival is really the festival of the withdrawal of the waters that covered the ground for six months, fertilized it with a supply of humus descended from the higher parts and carried by the Mekong, the “mother of waters”, or Ganga. It reminds us of the one the Egyptians celebrated when, around the autumn equinox, the waters of the Nile (September) [The length of the Nile is about 7000 kilometers, that of the Mekong is 4500 kilometers: its width varies greatly: it is 1500 meters at Kratie and 1000 at Phnom Penh] began to drop, which allowed farmers to plow the land and sow it. In Cambodia, the waters of the river begin to rise in June, and continue to increase until October. They sometimes reach 16 meters in Kratie, only 9 meters in Phnom Penh and even less the closer they are to the sea. The Great Lake, or Tonle Sap, which begins to grow in November, rises by 3 and 4 meters, overflows onto the plains up to 30 kilometers thanks to the rivers receiving the waters of the rains which have become abundant and reach up to a few kilometers from Ankorthom, the old and ancient capital of the Khmer doeum or “of the past”. The rise of the waters therefore lasts about five months, and the descent more than seven months. It is in October, when the flood waters begin to uncover the land, that people celebrate, as in Egypt, the festival of decreasing waters that I will describe here. [p 255 – 6]

Khmer Water Festival in a French popular periodical, 1873

In this huge almanach published by Edouard Charton during the 19th century, we find a remarkably detailed description of the making and performing of Phnom Penh race dugouts. Excerpts from Le Magasin Pittoresque, 1873, p 284 – 6 (out of 414!) [all articles uncredited]

Chez tous les peuples navigateurs, sous toutes les latitudes, la pirogue fut l’embarcation primitive, celle dont la

construction était la plus simple et la plus facile. Un tronc d’arbre aminci à ses deux extrémités et creusé par un

moyen quelconque, tel est le type originel de tout véhicule flottant, l’embryon pour ainsi dire du navire de haute mer; c’est encore la pirogue que l’on trouve aujourd’hui en usage chez les populations au milieu desquelles l’art de la construction navale est resté dans l’enfance. Au Cambodge bodge, à part quelques rares exceptions, ce genre d’embarcation né s’est conservé que pour les régates, pour la lutte de vitesse. Mais il est devenu bien difficile de trouver dans un seul bloc de bois les dimensions nécessairesà une pirogue de course. On en cite cependant quelques exemples. Voici, dans le cas où la pièce est assez longue, quel artifice on emploie pour donner à la pirogue la largeur convenable L’arbre choisi et abattu est ouvert dans toute sa longueur, sauf aux deux extrémités, par une fente étroite on recherché généralement pour cet usage l’arbre appelé tien-moc (Fopes, famille des diptérocarpées), à cause de sa solidité et de sa résistance. Puis on vide par cette fente tout l’intérieur du tronc, de manière à né laisser aux parois que l’épaisseur voulue. On travaille alors, au moyen de coins et d’arcs-boutants dont on augmente peu à peu la longueur, à écarter l’une de l’autre les deux lèvres de la fente longitudinale, jusqu’à ce que la pirogue ainsi formée soit arrivée à une largeur suffisante. Les indigènes, afin de faciliter cette opération, ont recours à des fumigations réitérées dont l’effet est d’assouplir les fibres du bois. Ce dernier procédé est analogue à celui de nos arsenaux, où l’on met à l’étuve les grosses pièces que l’on veut façonner a simple ou double courbure. Un système de couples en bois dur assujettis à l’intérieur maintient l’écartement des flancs de l’embarcation et sert à la consolider. La pirogue est garnie de ses bancs, grattée et polie. On mastique soigneusementles gerçures qui auraient pu se produire, et l’on recouvre toute la coque d’un vernis brillant fabriqué avec l’oléorésine du cay-diau (Dipterocarpics). Quelques sculptures à l’avant et à l’arrière, sur les parties où la lisse se relève en courbe gracieuse, achèvent de donner a l’embarcation toute l’élégance désirable.A Pnom-Penh, capitale du royaume, le théâtre des fêtes nautiques est admirablementchoisi. Là, presque devant

le palais du roi, le grand fleuve Mé-kong se partage en trois bras deux descendentà la mer à travers les provinces de la basse Cochinchine le troisième remonte au lac d’Angkor, qui sert de déversoir au trop-plein du fleuve. C’est au point de partage de cette énorme masse d’eau, sur l’espèce de lac formé par le confluent des quatre bras, que se déploie l’arène. Les fêtes de l’anniversaire du couronnement du roi, de celui de sa naissance, l’arrivée d’un souverain étranger, d’un hôte illustre, sont autant d’occasions ou les Cambodgiens, peuple et mandarins, bateliers, soldats, cornacs et pécheurs, viennent à rangs pressés se réjouir d’un spectacle si plein pour leurs yeux d’un merveilleux attrait. C’est en vain que, la veille encore, les danseuses du roi, parées de leurs plus brillants costumes, ont pendant vingt-quatre heures charmé la foule admise dans l’intérieur du palais à contempler les splendeurs de son souverain; c’est en vain que les éléphants de guerre en grand appareil, que les chars attelés de boeufs, ont défilé avec pompe et ont lutté de vitesse devant le monarque: tout est oublié, et la fête serait incomplète si les grandes pirogues né venaient à leur tour se disputer le prix de la course.

[Among all navigating peoples, in all latitudes, the canoe was the primitive boat, the one whose construction was the simplest and easiest. A tree trunk thinned at both ends and hollowed out by some means, such is the original type of any floating vehicle, the embryo, so to speak, of the ocean-going vessel; it is still the canoe that we find today in use among populations among whom the art of shipbuilding has remained in its infancy. In Cambodia, apart from a few rare exceptions, this type of boat has only been preserved for regattas, for speed racing. But it has become very difficult to find in a single block of wood the dimensions necessary for a racing dugout. However, a few examples are cited. Here, in the case where the piece is long enough, is the artifice used to give the canoe the suitable width: the tree chosen and felled is opened along its entire length, except at the two ends, by a narrow slit. For this purpose, the tree called tien-moc (Fopes, family of dipterocarpi) is generally sought, because of its solidity and resistance. Then, through this slit, the entire interior of the trunk is emptied, so as to leave the walls with only the desired thickness. Then, by means of wedges and flying buttresses, the length of which is gradually increased, the two lips of the longitudinal slit are separated from each other, until the canoe thus formed has reached a sufficient width. The natives, in order to facilitate this operation, resort to repeated fumigations, the effect of which is to soften the fibers of the wood. This last process is similar to that of our arsenals, where large pieces that we want to shape with a single or double curve are put in the oven. A system of hardwood couples secured inside maintains the spacing of the sides of the boat and serves to consolidate it. The canoe is furnished with its benches, scraped and polished. Any cracks that may have occurred are carefully puttyed, and the entire hull is covered with a shiny varnish made with the oleoresin of the cay-diau (Dipterocarpus). A few sculptures at the front and back, on the parts where the rail rises in a graceful curve, complete the process of giving the boat all the desirable elegance.

At Phnom Penh, the capital of the kingdom, the scene of the nautical festivals is admirably chosen. There, almost in front of the king’s palace, the great Mekong River divides into three branches, two of which flow down to the sea through the provinces of lower Cochinchina, the third flows up to Lake Angkor, which serves as an overflow for the river’s overflow. It is at the point where this enormous mass of water divides, on the kind of lake formed by the confluence of the four branches, that the arena is deployed. The celebrations of the anniversary of the king’s coronation, of his birth, the arrival of a foreign sovereign, of an illustrious guest, are all occasions when the Cambodians, people and mandarins, boatmen, soldiers, mahouts and fishermen, come in hurried ranks to rejoice in a spectacle so full of marvelous attraction for their eyes. It was in vain that, the day before, the king’s dancers, adorned in their most brilliant costumes, had for twenty-four hours charmed the crowd admitted into the interior of the palace to contemplate the splendors of their sovereign; it was in vain that the war elephants in grand attire, that the chariots drawn by oxen, paraded with pomp and competed for speed before the monarch: all is forgotten, and the festival would be incomplete if the great canoes did not come in their turn to compete for the prize of the race.]

Boat Festival at Champasak in 1866, as seen by Francis Garnier

The Kingdom of Champasak [la ຈຳປາສັກ] or Bassac in French literature (1713 – 1904) was a Lao kingdom under Nokasad, a grandson of King Sourigna Vongsa, the last king of Lan Xang and son-in-law of the Cambodian King Chey Chettha IV. Here, Francis Garnier alluded to the last King of Bassac, “a handsome young man of 24 or 25”, Kham Souk, who reigned from 1863 to 1899. The celebrations took part at a time the Champasak kingdom was eying an exit from Siamese tutelage. Excerpts from Voyage d’exploration en Indo-Chine (1885):

Une grande fête se préparait dans la vallée du Mékong : c’était celle par laquelle les populations ont l’habitude de célébrer la fin de l’inondation et de préluder à la récolte. Son nom populaire est Hena Song ou « Fête des bateaux » ; elle a pour but de rendre un hommage de reconnaissance au fleuve, en raison de la fécondité et de la richesse qu’il apporte au pays. Le gouvernement de Ban Kok a su faire tourner habilement au profit de sa politique ces réjouissances populaires, et c’est au milieu de cette fête, en présence du concours de peuple qu’elle attire, que le roi de Bassac et tous les gouverneurs de province doivent solennellement renouveler, dans une pagode, leur serment d’obéissance au roi de Siam. Tout est calculé pour rehausser l’éclat de cette cérémonie et pour qu’elle fournisse un aliment de plus à l’allégresse publique. [p 135]

Ce fut le lendemain qu’eut lieu la prestation de serment. Un bonze faisait le personnage du souverain de Siam, et le roi de Bassac lui jura obéissance et fidélité. En même temps, les eaux du Mékong furent solennellement consacrées et bénites; c’était là sans doute, à l’époque de l’indépendance, la partie essentielle de la fête. La présence de M. de Lagrée et des quelques baïonnettes françaises qui l’escortaient né contribua pas peu à sa splendeur. Le cliquetis des armes manoeuvrées à l’européenne remplit le roi de fierté et les nombreux spectateurs d’admiration. Pour comble de bonheur, un fils naquit ce jour-là au roi de Bassac. Sa joie, le soir, alla jusqu’à l’ivresse. Des régates sur l e fleuve occupèrent le troisième jour des fêtes et en furent la partie la plus intéressante à cause de l’animation, de la variété des costumes et de la couleur locale. Ces longues pirogues, dont quelques-unes atteignaient jusqu’à 28 mètres de long, manoeuvrées à la pagaie par plus de 60 hommes, portaient chacune les couleursd’un village ou d’une pagode.

Des bouffons, le visage abrité derrière un masque grimaçant, se démenaient avec rage au milieu des rameurs dont ils excitaient l’ardeur par leurs chants et leurs propos lascifs. L’équipage leur répondait en poussant des cris en cadence ; les nombreuses pagaies frappaient l’eau avec une précision merveilleuse, et la barque semblait disparaître sous l’écume soulevée autour d’elle. Les rameurs khas se faisaient surtout remarquer par un costume d’une étonnante simplicité : une feuille de vigne… en toile, attachée par un fil autour de la ceinture, était le seul et presque invisible ornement de ces bustes bronzés qui paraissaient émerger du fleuve, tant la pirogue qui les portait était rase sur l’eau.

Le lendemain, notre campement né désemplit pas. Soit curiosité, soit politique du roi, tous les mandarins, tous les chefs de tribus sauvages, accourus pour la solennité, vinrent saluer M. de Lagrée, et furent pour lui une source de renseignementset une nouvelle occasion d’étude. Le 28, celte brillante série de fêtes se termina par une illumination du fleuve et un nouveau feu d’artifice. De grandes carcasses en bambou, représentant des objets divers et chargées de feux de couleur, furent lancées au courant sur des radeaux. Sur tous les points du fleuve on voyait de fantastiques lueurs répercutées dans l’onde. Parfois le feu gagnait la carcasse elle-même, et tout s’abîmait dans un embrasement général. La science de nos artificiers et de nos machinistes saurait produire de plus grands effets avec ce genre d’illumination, mais elle né disposera jamais d’une nuit et d’un fleuve pareils. [p139]

[A great festival was being prepared in the Mekong Valley: it was the one by which the populations are accustomed to celebrate the end of the flood and to ready themselves to the harvest. Its popular name is Hena Song or “Festival of the boats”; its aim is to pay a tribute of gratitude to the river, because of the fertility and wealth that it brings to the country. The government of Ban Kok has skillfully turned these popular rejoicings to the advantage of its policy, and it is in the middle of this festival, in the presence of the crowd that it attracts, that the King of Bassac and all the provincial governors must solemnly renew, in a pagoda, their oath of obedience to the King of Siam. Everything is planned to enhance the splendor of this ceremony and to provide additional fuel for public joy. [p 135]

It was the next day that the oath-taking took place. A bonze played the part of the sovereign of Siam, and the King of Bassac swore obedience and fidelity to him. At the same time, the waters of the Mekong were solemnly consecrated and blessed; this was doubtless, at the time of independence, the essential part of the festival. The presence of M. de Lagrée and the few French bayonets which escorted him contributed not a little to its splendor. The clatter of weapons maneuvered in the European manner filled the King with pride and the numerous spectators with admiration. To crown his happiness, a son was born that day to the King of Bassac. His joy, in the evening, went as far as drunkenness. Regattas on the river occupied the third day of the festivities and were the most interesting part because of the animation, the variety of costumes and the local color. The long pirogues, some of which reached up to 28 meters long, paddled by more than 60 men, each wore the colors of a village or a pagoda.

Jesters, their faces hidden behind grimacing masks, struggled furiously among the rowers, arousing their ardor with their songs and lascivious remarks. The crew responded by shouting in rhythm; the many paddles struck the water with marvelous precision, and the boat seemed to disappear under the foam raised around it. The Khas rowers were especially noted for a costume of astonishing simplicity: a vine leaf… in canvas, attached by a thread around the belt, was the only and almost invisible ornament of these bronzed busts that seemed to emerge from the river, so low was the pirogue that carried them on the water.

The next day, our camp was intensely visited. Whether out of curiosity or the king’s policy, all the mandarins, all the chiefs of wild tribes, who had rushed for the solemnity, came to greet M. de Lagrée, and were for him a source of information and a new opportunity for study. On the 28th, this brilliant series of festivities ended with an illumination of the river and a new fireworks display. Large bamboo carcasses, representing various objects and loaded with colored fires, were launched into the current on rafts. At all points of the river one could see fantastic lights reflected in the water. Sometimes the fire reached the carcass itself, and everything was destroyed in a general blaze. The science of our artificers and our machinists could produce greater effects with this kind of illumination, but it will never have at its disposal a night and a river like that.” [p139]

Tags: traditions, water festival, celebrations, 1900s, boats, boat races, Laos, Mekong River, Tonle Sap, Tonle Sap Lake

About the Author

Adhémard Leclère

Self-taught orientalist and ethnologist, ardent socialist converted to Georges Clémenceau’s patriotic republicanism, founder of one of the richest collections of Khmer studies outside of Cambodia (in his French hometown of Alençon), Adhémard Leclère (12 May 1853, Alençon, France — 16 March 1917, Alençon) remains a rara avis in the small world of Khmerology.

Born into a working-class family, Leclère was a 17-year old typographer when he joined the French Socialist Party. soon becoming the editor-in-chief of a left-wing periodical, Le Prolétaire (The Proletarian). A few years later, however, he left France for Cambodia with wife and child, becoming ‘résident’ (governor) in the French protectorate of Cambodia, first in Kampot (until 1890), then Kratie-Sambor (1890−1894), Kratie, and finally Phnom Penh, where he served as résident-maire from 1899 to 1903. In total, he spent 24 years in Cambodia.

In his field research, he was helped by his first wife, Henriette Leclère née Brière, and his first daughter Francia, understanding that a man alone could not obtain the confidence of local villagers. After Henriette’s premature death in France, he remarried and started to collect, translate and comment numerous Khmer manuscripts and documents.

Collecting with the same enthusiasm popular tales and artifacts, learning by himself Khmer, Sanskrit and Pali languages (and thus inflaming the ire of established linguists and academics), he wrote extensively about Cambodian mores and traditions, Theravada Buddhism, archeological findings and the many topics that aroused his interest.

In 2011, French historian Grégory Mikaelian published a complete Leclère’s biography (Un partageux au Cambodge), adding to it the extensive inventory of the Leclère Archives deposited at the Musée d’Alençon.