gopura

sk गोपुर gopura, "elaborate gateway" |

Gopura in Indian architecture refers to a tower above a gateway or archway, "towers at the entrances of a temple". The term is also used as saṃdoha, a "meeting place" of the Yoginis.

by Damian Evans

A reevaluation of the Koh Ker urban plan based on new archaelogical and scientific explorations since 2006.

pdf 2.9 MB

In preamble, the author remarks that “In 2006 and 2007 the Apsara National Authority conducted the very first modern scientific excavations at Koh Ker, consisting of small test excavations at three different sites in the central temple precinct under the direction of Ly Vanna. These sites were: the bank of the artificial pond known as Trapeang Sre; on the north bank of the Rahal, at the laterite outlet identified by [Etienne] Aymonier; and a possible canal feature in the vicinity of the structures 200 m east of the eastern gopura of Prasat Thom, which the authors give the name Prasat Srut (called Monument A by Lunet de Lajonquière).”

Further research, in particular by Claude Jacques, Christophe Pottier and the Hungary-APSARA Archaelogical Team at Koh Ker, have challenged the notion of an enclosed city built by Jayavarman IV, as speculated in the 1930s by Henri Parmentier. On that respect, the author notes: “Recent research disputes the existence of the pre-Angkorian enclosure of Banteay Chhoeu in Siem Reap; demonstrates that 8th to 9th century occupation at Hariharālaya extended well beyond the temple enclosures; and proves that the 9th century “walls of Yaśodharapura” were not city walls but actually dykes to control water that were built in the 11th century. It would seem, therefore, that most Khmer cities since the pre-Angkorian period might be defined as “open cities” characterized by a “remarkable rural-urban continuum” (Pottier 2006: 66) and fundamentally unconstrained by enclosures or formal urban planning. In fact there is, to my knowledge, no compelling evidence in the published literature that formally bounded urban areas were constructed at all in northwest Cambodia until the 12th to 13th centuries. Furthermore, even then ‘bounded cities’ such as the Angkor Thom of Jayavarman VII (Gaucher 2003) show evidence of a contemporary low-density settlement pattern stretching far beyond their walls (Evans 2007; Pottier 1999), and new data from the 2012 lidar acquisition shows that the formally planned grid of city streets previously thought to be the defining urban characteristic of Angkor Thom is not simply an intra-mural phenomenon.”

As for the orientation of the monuments at Koh Ker, ” much has been made of the unusual orientation of the monuments at Koh Ker. In fact, most of the monuments here are oriented quite conventionally, either towards the east or with a measure of deviation to the northeast (as with a great many sites at Angkor, for example in the Neam Rup area but also Banteay Kdei, the Srah Srang, Prasat Trapeang Ropou, the walls of Angkor Thom, the East Baray, Banteay Samre, and further afield at Preah Khan of Kompong Svay, Banteay Chhmar, Sambor Prei Kuk…). A small number of temples at Koh Ker face west; although this is indeed relatively rare, it is by no means unknown (Angkor Wat being only the most famous example). What remains as highlyunusual and quite specific to the Koh Ker area is the array of temples oriented towards the southwest. Parmentier’s (1939: 16) suggestion that those located to the east of the Rahal are so oriented because of the existence of the reservoir was a satisfactory explanation, as far as it went; however, it could not explain the orientation of the great liṅga shrines to the north.”

All in all, what the study invites us to do is to depart from the notion of a “capital city” built in a short amount of time for one single purpose, and then suddenly abandoned: “The research on Koh Ker described here was begun many years ago with the idea that Koh Ker was essentially a single period site, and that it would therefore provide an excellent case study for revealing patterns of settlement and water management that were characteristic of the second quarter of the 10th century AD. Parmentier was fascinated with Koh Ker for similar reasons. In his view, the fact that so much was achieved there in such a constrained period of time meant that it had the potential to reveal a period of Khmer art and architecture with great clarity, without the confusion and uncertainty commonly caused by the spatial and temporal complexities of Angkor. Paradoxically, however, what has emerged from recent research on Koh Ker is that it is indeed a special case, but not because it was ephemeral: but rather, because of the dissonance between the ostensibly brief periods of iconographic and epigraphic output and the much broader evidence for a very long and complex history of occupation.”

As the author points out, “as with other Khmer cities that developed over centuries and across various reigns, this “vast ritual complex” may be more accurately described as a vast palimpsest representing a succession of urban spaces, defying the idea of a single unitary conception of the city, and leading us eventually to a more nuanced assessment of its supposed exceptionality.”

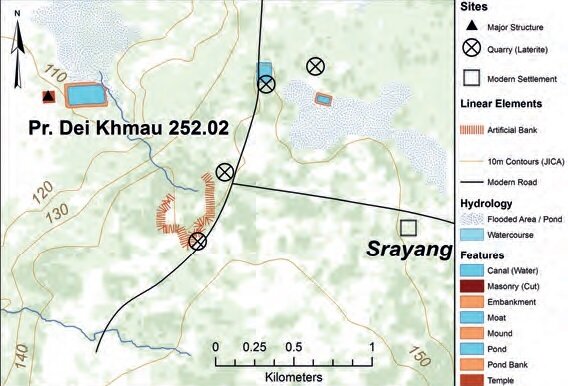

Photo: Laterite quarries near Srayang (by the author)

Tags: Koh Ker, archaeology, urbanism, urban development, Khmer dynasties, architecture, enclosed cities, urban planning

A Canadian-Australian researcher, Damian Evans (d. 12 Sept 2023, Paris, France) focused on archaeological landscapes in mainland Southeast Asia, in particular those of the Khmer Empire.

He specialized in using advanced remote sensing technologies such as airborne laser scanning (or “LIDAR”) to uncover, map and analyse the urban and agricultural networks that stretched between, and beyond, great temple complexes such as Angkor in Cambodia.

Fellow researcher with the University of Sydney, then the Institut Francais d’Etudes Asiatiques, then EFEO, he has published several essays on Angkorian archaeology and mapping.

“In 2015, his team carried out the most extensive airborne study ever taken by archaeologists – using a laser radar mounted on a helicopter to scan an area of the jungle in Cambodia comparable in size to greater London”, read his obituary in The Guardian.