Titaÿna

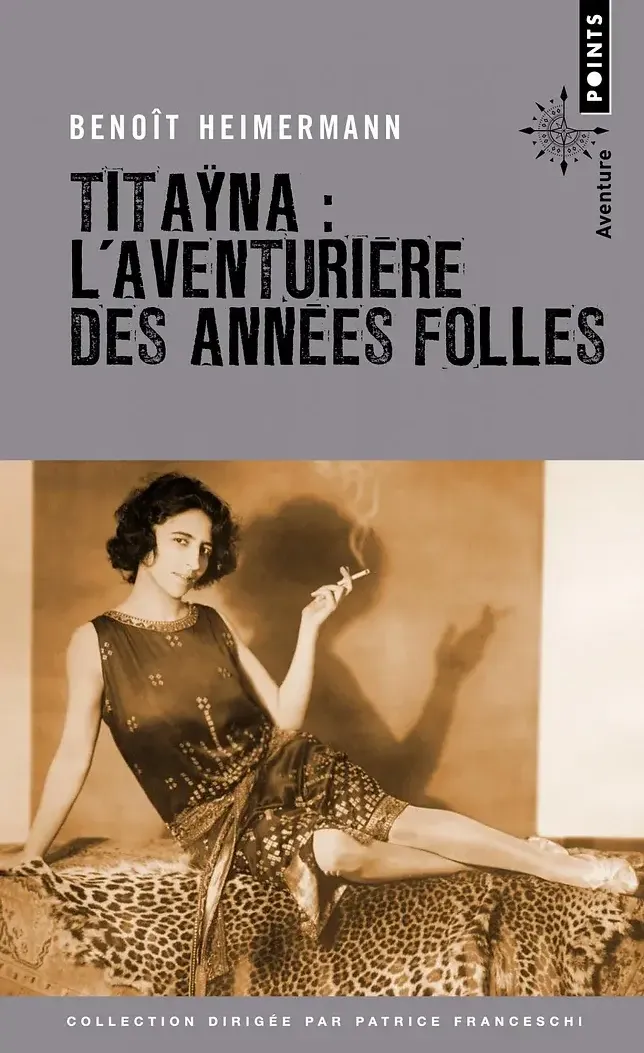

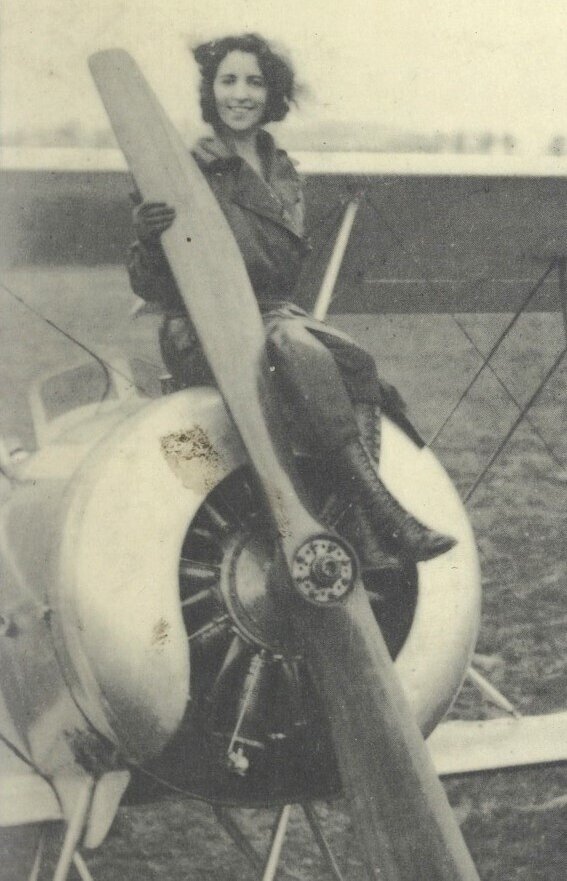

Titaÿna, pen-name of Elisabeth Sauvy or Sauvy-Tisseyre (22 Nov. 1897, Mas Richemont, Villeneuve-de-la-Raho, France — 13 Oct 1966, San Francisco, USA) was a French aviatress, reporter at large, photographer, known as the ‘Queen of Tout-Paris’ in the 1920s-1930s.

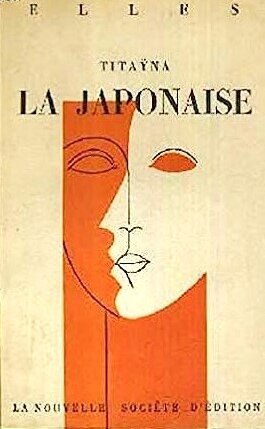

Early divorced from her first husband, the indefatigable traveler started to fly airplanes in her youth, and went to Japan to be part of the entourage of Japanese Princess Fusako Kitashirakawa. After surving a deadly car crash, she was granted a life pension which allowed to travel around the world, often flying her own airplane. Writing for prestigious French publications such as Vu, Voilà, L’Intransigeant, Paris-Soir, she interviewed worldwide leaders such as Mustafa Kemal, Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, Primo de Rivera or the head of the Corsican insurrection Romanetti.

Her fascination for Cambodia was not limited to her 1928 adventure in Angkor: in Marie Claire (9 July 1937, n 20, tp 30, he famous women’s magazine being only 4 months old), she published ‘Une histoire vraie par Titayna: Saramani, princesse et danseuse’, about Suzanne Meyer, the daughter of Royal Ballet dancer Saramani and author Roland Meyer, who was then a celebrated “exotic dancer“in France. Suzanne-Saramani was to die of privation in occupied Paris in 1942, at age 28.

With her wit and charm, Titayna (a nickname took after after a legendary Catalan female figure) was equalled to notorious reporters such as Pierre Mac Orlan (who penned the preface to her 1925 novel, La bete cabrée), Joseph Kessel, Blaise Cendrars or Albert Londres. Her work as a literary translator commanded author Jean Giono’s admiration. A teenager during World War I, she was to “remember in order to forget”: “1900 était né sur une bicyclette polka. Les voilettes de tulle enveloppaient de leur illusion les adultères d’avant guerre, et les orgues de barbarie donnaient aux provinciales le goût d’amours viennoises. /J’oublie./ Ma première communion eut pour cadre un grand parc de couvent, où durant neuf ans mon mysticisme révolté s’élevait vers les fleurs des vitraux et retombait avec elles sur les reposoirs aux parfums trop violents. /J’oublie./Il y eut une guerre qui bombarda la salle où je « séchais » sur une version de Tite-Live. Ma mère en blanc sentait l’hôpital, mon père fut tué en lisant du grec. J’avais un grand voile de crêpe. Le jazz-band commençait. De la jeunesse qui s’ignore. Un tourbillon grisant comme une noyade. Des soûleries d’exotisme, un voyage rapide en Europe ou en Afrique et plus lointain à Montparnasse. La mort frôlée comme une soeur aimée et contagieuse./J’oublie./ Le règne du simili : faux succès, faux amour, faux regrets, fausses haines./ J’oublie./” [“1900 was born on a polka bicycle. Tulle veils wrapped pre-war adulteries in illusion, and barrel organs gave the provincials the taste of Viennese dalliances. /I forget./ My first communion was set in a large convent park, where for nine years my rebellious mysticism rose towards the flowers of the stained glass windows and fell with them on the altars with too violent perfumes. /I forget./ Then came a war that bombed the room where I “dried off” on a version of Livy. My mother in white smelled like a hospital, my father was killed while reading Greek. I had a large crêpe veil. The jazz band was starting. Unaware youth. An exhilarating whirlwind like drowning. Exotic drunkenness, a quick trip to Europe or Africa and, even further, to Montparnasse. Death brushed past like a beloved and contagious sister./I forget./ The reign of imitation: false success, false love, false regrets, false hatreds./ I forget./”

After the death of brother Pierre Sauvy during the English attack on Mers El-Kébir in 1941, Titayana shifted her political involvment to collaborationist and antisemitic activism, leading to her arrest and after World War II in France. Self-exiled in San Francisco after her second husband’s death, she spent her remaining years with the Italian author and bookseller Giovanni Scopazzi.

Titayna’s writing belongs to the tradition of European travel writers loathing the “civilized world” and yet reluctant to embrace the Rousseauist myth of the ‘bon sauvage’. Libertarian, she writes also as a woman very much aware of the devastation of the patriarcal order. In Loin (1929, Flammarion, Paris), for instance, her potent diary of her travel to Oceania, she writes: “Quand les missionnaires y vinrent, ils firent un immense autodafé de pièces d’art primitif d’un intérêt certain, d’une valeur non moins certaine. Et c’est ce que j’appellerai une mauvaise opération commerciale. Puis, ils mirent les garçons d’un côté dans un internat, les filles d’un autre dans un couvent et séparés les uns des autres par un bras de mer. Comme filles et garçons étaient de beaux animaux, pour qui faire l’amour dans les bois

était plus que naturel, mais nécessaire, ce fut pour le moins une faute d’élevage […] Et l’Océanien, quand j’y songe, a plus de force que toutes les philosophies même chinoises, ils ont inventé ce

boomerang plus efficace qui fait que tout ce qui fait notre désespoir, ce que nous appelons l’amour ou bien les signes de croix, tout ce que nous jetons vers le ciel, ici fait un petit tour en l’air, revient, et l’on n’en parle plus.” [“When the missionaries came there, they made an immense auto-da-fé of pieces of primitive art of doubtless interest, of no less certain value. And that is what I would call a bad commercial operation. Then, they put the boys on one side in a boarding school, the girls on the other in a convent and separated from each other by an arm of the sea. As girls and boys were beautiful animals, for whom making love in the woods was not only natural, but necessary, it was at least a fault of breeding […] And the Oceanian, when I think about it, has more power than all the philosophies, even Chinese, they invented this boomerang more effective which makes everything that causes our despair, what we call love or else the signs of the cross, everything that we throw towards the sky, here takes a little turn in the air, comes back, and we don’t talk about it anymore.”]

Irreverent and snidely sensuous, she could title the second part of that same book ‘A l’ombré des jeunes filles enceintes’, a clearly un-Proustian image complete with the mysterious epigraph: “Ah ! beaux garçons inoccupés…”, and containing a ‘Plaidoyer pour l’anthropophagie’ (A Plea For Anthropophagy). She also noted: “L’Amérique est partie sur un idéal de pure littérature primaire : la Liberté. Vous pouvez en avoir les notions courantes dans tous les manuels. Pour assurer cette liberté, elle a instauré le travail, pour assurer ce travail, elle a tué cette Liberté. Ils en sont actuellement à travailler pour bien manger.” (p 12) [“America started from an ideal completely belonging to basic literature: Liberty. You can get all conventional versions of it in any manual. In order to guarantee that Liberty, America promoted work, and in order to strenghten work she killed that same Liberty. They have reached the point that they are now working only to stuff themselves.”].

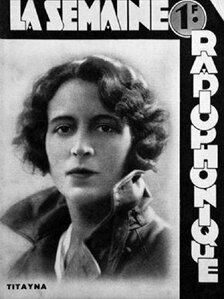

Renowned French journalist Joseph Delteil would note in his diary on Dec 15, 1925 : “Vu Titaÿna ; un œil de gazelle dans un corps d’avion. Elle doit faire l’amour avec les palmiers.” [Met Titayna: gazelle eye and airplane body. Surely she makes love to the palm trees.]

Loin, cover (Flammarion, Paris, 1929, 122 p) [note the Star of David floating to the left of the illustration. In Loin, her growing judeophobia led her to write: “C’est une histoire juive que j’ai cueillie pour vous aux îles Gambier : Un jour, Isaac Salomon, qui était peut-être le Juif errant, après avoir franchi monts et plaines, traversa les Océans et débarqua dans les îles du Sud. Là, il vit plonger les jeunes hommes et comment ils trouvaient parfois une perle dans les nacres revendues aux Chinois. Il étudia leurs poids et leurs reflets, leur chair et leur forme et comment le soleil du soir les irise différemment. Mais il né s’installa pas acheteur sur place ; les îles basses semblent radeaux abandonnés et les Juifs préfèrent la fièvre des grandes cités au vent marin. Il repartit et se fit courtier en perles à Monaco, où près des salles de jeu, cette autre plongée, se trouvent des perles à vendre, plus souvent qu’au bord du lagon.” [“Here is a Jewish story that I picked up for you in the Gambier Islands: one day, Isaac Solomon, who was perhaps the Wandering Jew, after passing by mountains and plains, crossed the oceans and landed in the southern islands There he saw the young men diving and how they sometimes found a pearl in the mother-of-pearl later sold to the Chinese. He studied their weights and reflections, their flesh and their form and how the evening sun give them a different iridescence. But he did not settle there to buy the pearls on the spot — the low islands look like abandoned rafts and the Jews prefer the Big City fever to the sea breeze. He left and became a pearl broker in Monaco, where near the gambling halls — this other form of diving -, are pearls for sale more often than on the lagoon shore.”] (p 62) If this rather nasty aparte was an attempt to explain the origin of the name Solomon Islands, it is a total failure: sailors gave that name to the archipelago in reference to the mythical city of Ophir mentioned by King Solomon in the Bible, long after the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña had been the first European to visit these faraway islands in 1568.]

And a portrait by Man Ray after her return from Indochina and her World Tour in 1928:

See Francois-Xavier Bibert’s documented blog post on ‘Titayna, Gorgeous Adventuress, Reporter and Airplane Pilot’.