Titayna: How I Stole the Head of an Angkor Buddha

by Titaÿna

The flamboyant Titayna and her Surrealist 'gratuitous art' in Angkor Wat. Provoking the gods, challenging the humans, asking a question that still haunts us.

- Publication

- Vu, Journal de la Semaine, Paris, n. 5 & 6 | ADB Digital Document

- Published

- 1928

- Author

- Titaÿna

- Pages

- 3

- Languages

- English, French

pdf 4.8 MB

‘One throw of the dice never will do away with chance’, had written French symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé. Dare-devil globe-trotter, aviatress, foreign correspondent and ardent feminist Titaÿna had this profund remark very much in mind, as well as a clear inclination for the Surrealist ideal of ´acte gratuit´ (gratuitous act) when, visiting Angkor at tbe end of 1927, she decided to steal a Buddha head. Just for the heck of it, or was it her way to bring spirituality to the ‘Occident barbare’ (the barbarous West)?

It is clear that lucre and a dubious thirst for fame was not behind the young woman’s impulse, as it had been five years later when André Malraux attempted to plunder Banteay Srei sculptures. As soon she had brought the stone head to Paris, she sought to give it ‘back’ to the Institut de France, to the Ministry of Fine Arts, to Albert Sarraux, to whomever could reclaim the artefact and bring it back to Angkor. She stages a kind of art installation avant-la-lettre: who will take responsibility for the divine head? Cambodia was not an independent state yet, at that time, and France exerted tutelage on the Khmer ruins. And while Malraux considered himself way above the hoi polloi, there is a clear purpose in Tityana’s act: provocatively call out the practice of so many “wealthy tourists“to just lift out parts of the Khmer temples as “souvenirs”.

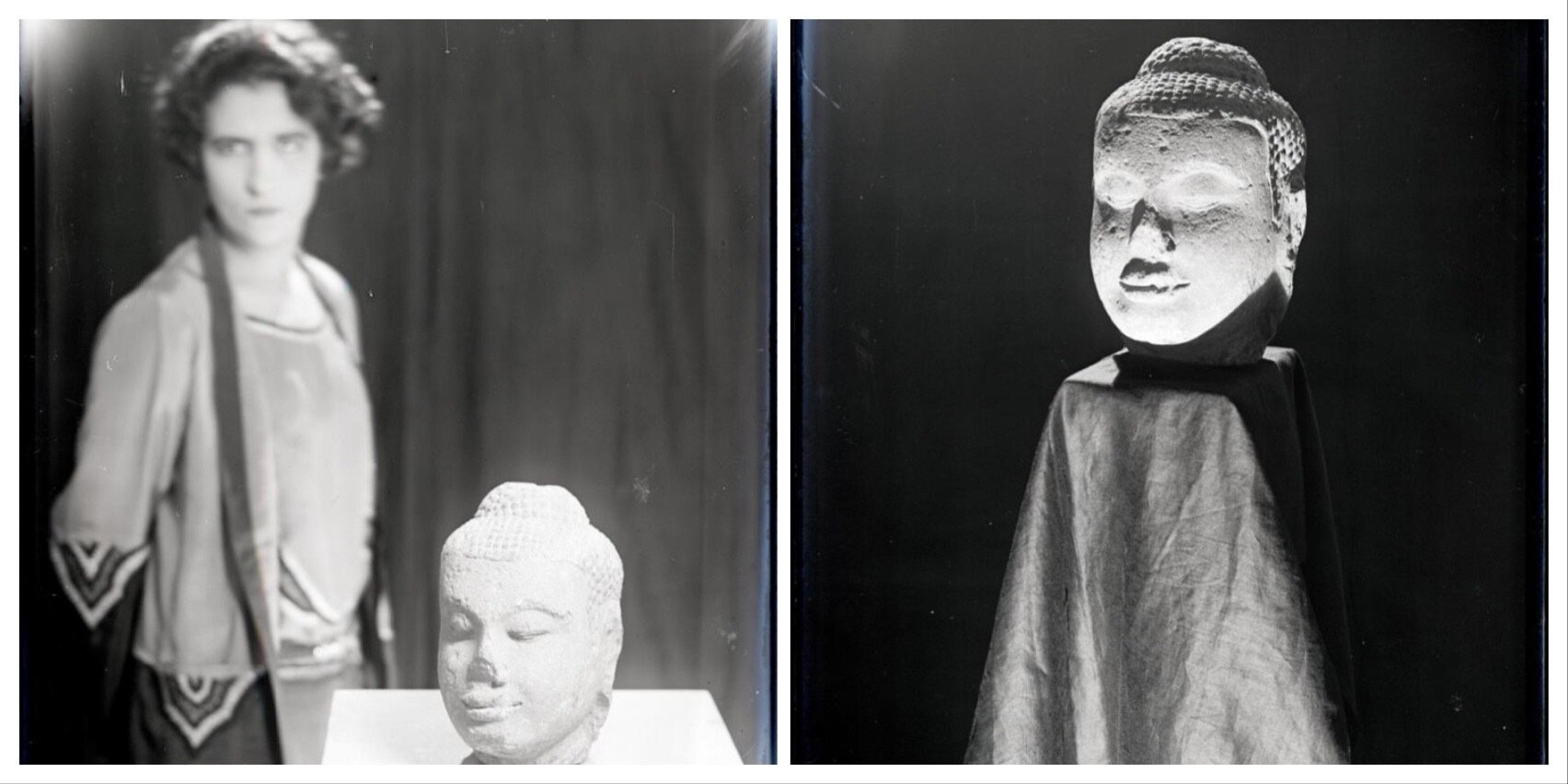

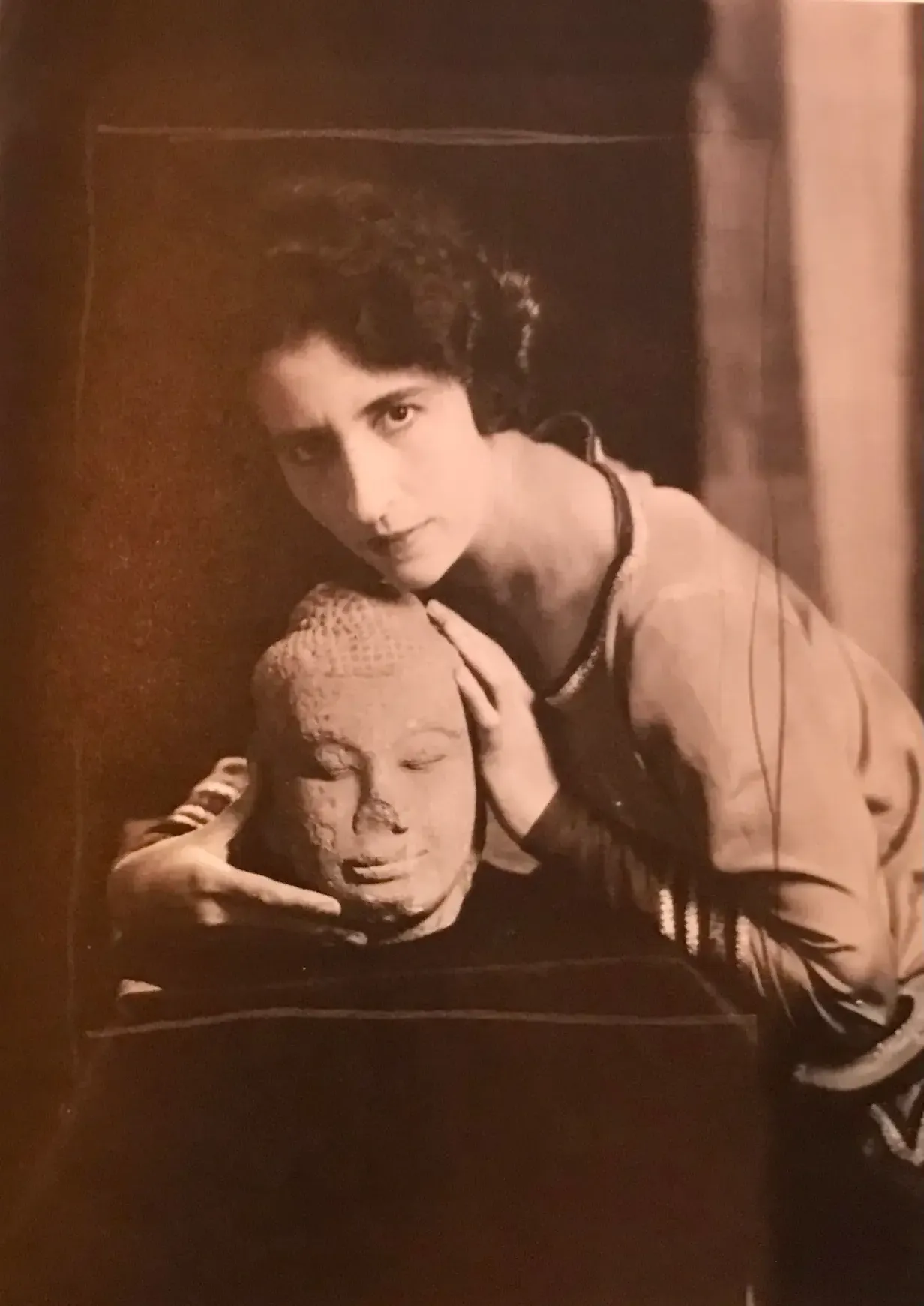

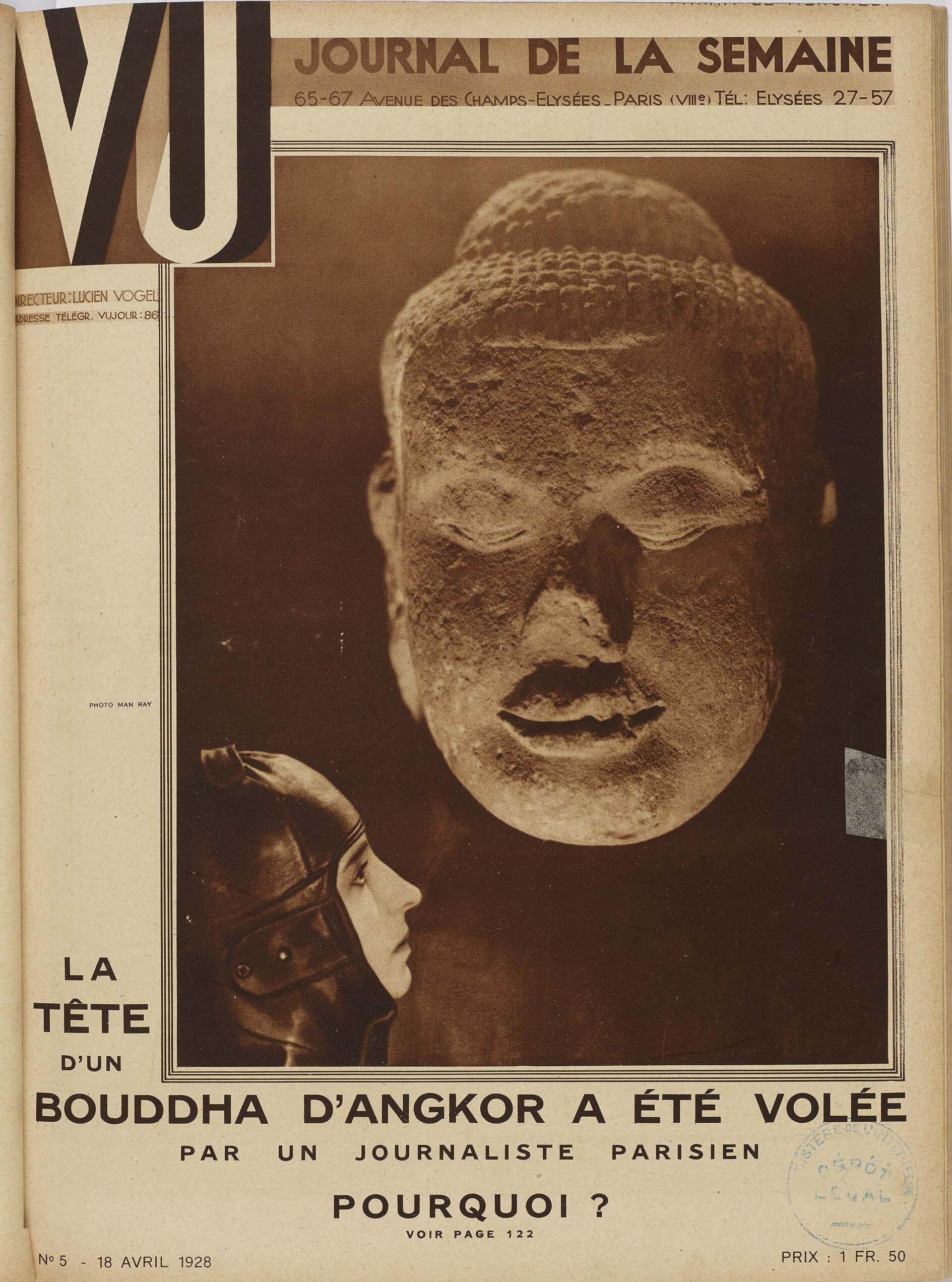

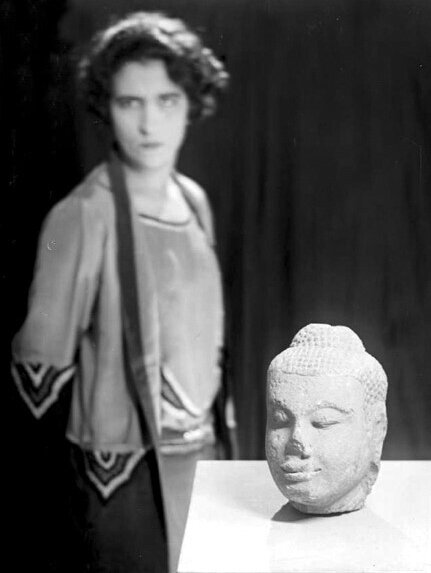

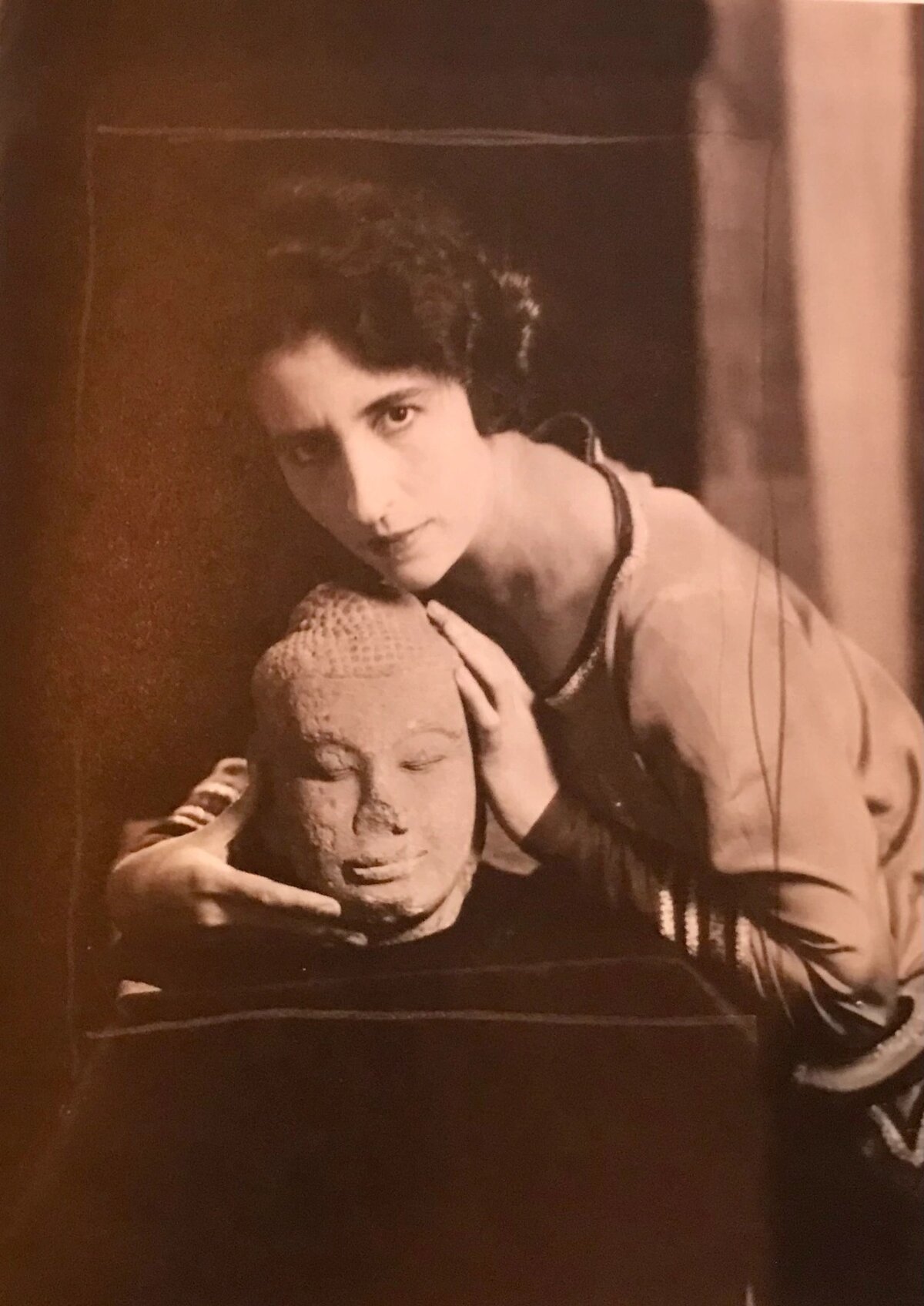

The adventurous and unpredictable Titayna was to narrate the odyssey of the Angkorean Buddha head in the columns of Vu, Journal de la Semaine, a left-wing publication to which she contributed to. And surrealist photographers Man Ray and Germaine Krull captured her wandering through Paris with her heavy head, her god-like burden. Germaine Krull, then one of the most respected art photographers in Europe, in particular for her nudes, would come to live in Thailand after World War II, publishing three books about Siamese culture and folklore [cf KRULL Germaine & MELCHERS Dorothea, Tales from Siam, London, Robert Hale, 1966], and managing the renovated Oriental Bangkok Hotel [now the Mandarin Oriental Bangkok] from 1946 to 1966. Germaine also worked on a project about Southeast Asian sculptures with André Malraux.

A few years later, when Europe was engulfed in the throes of fascism and war, the publication and the writer took two radically different paths: Vu became the first European media outlet to publish photographs of the Nazi death camps (as soon as in its 3 May 1933 edition), while Titayna was jailed for collaborationism, blacklisted by Life Magazine and nevertheless fled to…the USA.

The adventure of the stolen head, as told with Titayna’s elegant and brash style (her journalistic reporting has been compared to Blaise Cendrars, Paul Morand, Albert Londres, and other luminaries’ dispatches) deals with many ethical issues that have been discussed in the recent years, especially when she remarks: “Comment s’étonner alors de ce qui m’avait été dit au Japon et que j’avais refusé de croire : Angkor finira peu à peu dans les musés étrangers du monde entier.” And in line with the enigmatic beauty, it starts with a visit to Angkor by night.

For the first time ever, we publish here the full-text of Titayna’s account, with our English translation (from Vu, 5 (18 Apr 1928) and 6 (26 Apr 1928)[1].

Comment j’ai volé la tete d’un bouddha d’Angkor [How I Stole the Head of an Angkor Buddha]

“Oui, j’ai volé.

J’étais arrivée en Indochine non point sur un de ces paquebots à base de fonctionnaires corses ou de

Bovary croyant vivre la grande aventure en changeant de cabine la nuit, mais j’y étais venue, en noyant longuement dans les eaux tièdes de l’Océanie un reste de préjugés européens, en haïssant l’hypocrisie anglo-saxonne par des séjours en Australie ou aux Philippines.

Maintenant, me voici à Angkor, à 630 kilomètres du lamentable Saïgon, fui grâce à l’amabilité du Gouverneur de Cochinchine qui m’a confié une auto et un boy, grâce au Résident du Cambodge qui, à Pnom-Penh, me donna une autre auto, et un autre boy.

Sous le clair de lune, Angkor est là maintenant, mystère mort, enfoui dans cet autre mystère vivant:

la forêt.

Je quitte le confortable petit hôtel bas, où près de moi des Américains jouaient au poker en buvant

du whysky. Mes pas résonnent dans la nuit chaude, et je vais à leur rythme entre les éléphants de pierre, sur la gigantesque allée de dalles miroitantes comme de chaque côté, les étangs endormis

sous les lotus.

Seule dans Angkor, la nuit. Les voûtes sont emplies des cris des milliers de chauve-souris. Le

mouvement furtif d’un bonze animé un coin d’ombré, et les silhouettes hiératiques des bouddhas

aux yeux baissés se détachent sur des lambeaux de ciel lacté. Successivement, j’ai franchi les trois enceintes sacrées, chaque fois plus hautes d’Angkor Vat. Entre ses escaliers à pic, le choeur du temple se dresse, tabernacle vide, vers le ciei silencieux. Je grimpe les hautes marches pénibles, comme si l’homme n’avait jamais pu concevoir l’idée d’un Dieu sans calvaire. Tout autour de moi, par delà les trois enceintes sacrées, chaque fois plus basses, les singes de la forêt s’appellent et se répondent comme des hommes.

Assise sur les dalles disjointes d’une galerie du deuxième étage, appuyée contre ùn pilier, je laisse mon regard s’hypnotiser sur un bouddha de pierre, énigmatique comme tout ce qui fut inventé par nore inquiétude. La lune, trop blanche, découpe des ombres nettes, et dans les jeux de sa clarté, il me semble voir s’ouvrir vers moi des yeux fermés à toute misere.

Quelle heure est-il ? L’aube déjà jette sa tache d’or sur la pureté de la nuit. Le bouddha silencieux converse toujours avec mon âme partie, qui avec le jour me rejoint lentement, se recroqueville et s’endort, tandis que mes yeux retrouvés né voyaient plus devant eux qu’une statue de pierre, au grain moussu, émouvant au contact comme la chair, aux yeux clos sur une pensée absente, et dont la bouche aux lèvres ourlées semble avouer que les dieux connaissent le baiser.

Ce matin, j’ai interrogé mon guide : “- C’est facile, n’est-ce pas, d’emporter des morceaux

d’Angkor ? ” — Oui, c’est facile. Mais pourquoi tu n’achètes pas ? “

Acheter des morceaux d’Angkor ! Hélas! pour des sommes relativement minimes, les touristes, à

Angkor, obtiennent des débris de sculptures…” né pouvant, paraît-il, être utilisés pour la reconstruction de la ville”. N est-ce point le meilleur moyen de leur suggérer d’emporter un morceau

choisi par eux au cours de leurs promenades ? N’est-ce point ·systématiquement déprécier ce qui

est inappréciable ? Et comment s’étonner alors de ce qui m’avait été dit au Japon et que j’avais refusé de croire : Angkor finira peu à peu dans les musés étrangers du monde entier.

Avant d’arriver en Indochine, je connaissais déjà le grain du vieux grès cambodgien adouci par le temps, pour en avoir caressé des fragments surgis des valises constellées d’étiquettes, sur les paquebots ou dans le hall des palaces. Entre Manille et Hong-Kong, un diplomate américain m’avait fait admirer une pierre assez large d’où naissait, en bas relief, une tevada (danseuse sacrée) hallucinante. “Je l’ai emportée de votre Cambodge, m’avait-il dit … — Est-ce donc si facile ? — Je né sais pas si c’est facile pour les français … j’ai entendu raconter que des journalistes français avaient été arrêtés. Vous devez être surveillés, mais nous autres américains, on nous laisse tranquilles ! »

Je suis retournée voir mon bouddha ami. Une cassure ancienne sépare sa tête de son corps. Il me comprend et me parle. Un projet nait en moi.

Je sais aussi ce que je voulais savoir. Les touristes étrangers à monnaie facile circulent librement dans Angkor avec des guides achetés. Ils né se contentent point d’emporter des morceaux de pierre. Sans souci des dégradations, ils arrachent au monument ce qui les en a tentés davantage. Pour les plus rares Francais de passage à humeur indépendante et promenade solitaire, Îa surveillance

sera plus méfiante et plus hostile. “Que pourrait-il venir de bon d’un journaliste parisien ? … ” pensent de façon exagérée certains fonctionnaires coloniaux. Si ce fonctionnaire se piqué de littérature et n’a point été couvert de lauriers par la métropole … le reporter de passage n’a qu’à bien se tenir.

Sous l’écrasant soleil de midi, dans la réverbération des pierres qui font d’Angkor, à l’heure chaude, un brasier daubesque {dantesque?], je vais revoir ” mon bouddha.” Je dis déjà “mon” bouddha, et c’est avec son consentement. Je sais qu’il va m’accompagner vers l’Occident à civilisation barbare. Dans quel dessein né de l’infini ? Je né sais pas. Ce voyage du bouddha d’Angkor vers Paris me dira-t-il un jour sa destinée mystérieuse, ou bien, martyr, s’est-il sacrifié pour que Son Temple soit sauvé de l’éparpillement, plus à craindre que la mort douce dans l’étouffement des mousses et des lianes ?

J’ai pris la tête détachée et docile. Enroulée dans une veste de toile, elle pèse à mon bras. Et, la lourde

pierre appuyée sur ma hanche, je redescendis dans le soleil, vers les humains. Mais, en reprenant contact avec cette terre de mouvement, j’ai endossé comme un manteau le sens total des contingences mesquines, et des réalités.

- Hou boy, vite, ma voiture, ma note…

Je bouscule les garçons anamites, secoue mon boy, boucle mon sac, et me voici au volant. Il est cinq heures du soir. Saïgon est à 630 kilomètres. Je dois passer les fleuves sur des bacs, changer d’auto à Pnom-Penh.

Pour le cas où je serais signalée, je dois arriver à quai à Saïgon, avant l’ouverture du télégraphe demain matin. Je démarre dans un nuage de poussière rouge. Des kilomètres. Derrière moi la “forêt s’est refermée sur la ville morte.

Pour amortir les heurts, j’ai habillé “mon bouddha” de mon casque d’avion. Le compteur est à 100, 110…A droite et à gauche, les rizières fuient, moirées. La nuit s’est abattue, à la f?is épaisse et transparente et je la traverse comme une flèche derrière les cônes de lumière mouvante des phares.

Des étoiles sont tombées sur la route, ce sont les yeux des oiseaux de nuit qui se lèvent brusquement devant nous, se heurtent contre le radiateur ou le pare-brise, retombent tués ou restent accrochés, sanglants et ébouriffés. Dejà les vitres des lanternes sont brisées. Je n’ai pas lâché l’accélérateur…100…110…Des kilomètres. (A suivre)

Devant nous: une auto. La dépasser sur la route étroite. Arnver avant elle au bac. Réveiller les boys endormis, qui avec peine amarrent à la rive le radeau où nous prenons place. Leurs torses étroits et nus au-dessus de l’étoffe qui moule leurs hanches s’éclairent de la lueur tremblante des falots. Ils sont beaux. Leurs mouvements rythmés et silencieux font au tour de la divi ité qui m’accompagne un enroulement grave ct religieux. L’eau bruisse comme un crissement de feuilles mortes, les deux rives ont disparu. Et puis à nouveau la terre derrière le rideau de nuit, et la vitesse qui siffle aux oreilles… Saïgon. J’y parviens avec le jour. A quai, le grand paquebot des Messageries Maritimes m’attend, immobile. J’y pénètre comme on franchit une frontière. Je glisse dans les coursivcs, descends dés escaliers “interdits au public”. Aucune police au monde né “sait” un bateau aussi bien que moi. Les mains vides, et l’ame en paix, j’ai regagné ma cabine, suis tombée endormie sur ma couchette.

Des coups á ma porte. — Qu’est-ce que c’est? — La police! En pyjama, je suis allée ouvrir. Une dépèche m’avait signalée, comme je m’y attendais. Un jounaliste français n’est-ce pas… Le chef de la Sureté était là avec un ordre de perquisition, mais aussi avec toute la courtoisie et l’intelligence du monde. Par acquit de conscience, il visita mes bagages, vides, et mon innocente cabine. “Un conseil, me dit-il gentiment, méfiez-vous de votre passage a Marseille…”

A ce moment, un inconnu s’approche. Il me prie au nom du Gouverneur de Cochinchine de né pas aller au Gouvernement le soir, comme j’y étais invitée.…Brrr! On craint les compromissions, dans notre Troisieme République! Pourtant si M. Blanchard de Labrosse savait a quel point les repris de justice ont l’ame fraiche!

A bord, mon bouddha a réintégré ma cabine avant l’arrivée a Singapore. Mes voisins s’enferment chaque jour chez eux, et toute la coursive sent la noisette grillée: mais la reverie aigue que distille mon compagnon de pierre est de meilleure qualité encore.

Ceylan, Aden, Djibouti, Port-Said, Suez. Le Caire. Marseille. Comme un dieu qu’il est, mon bouddha est passé glorieusement au milieu des hommes inclinés devant son invisible présence.

Paris. Je crains une perquisition! Mon bouddha, momentanément, va me quitter. Pendant quinze

jours, je l’ai caché au Musée du Louvre. De là, il fit un tour à la Conciergerie. Il erra dans les coulisses de l’Institut, sous l’ombré de l’Obélisque, regarda Paris tourner autour de lui…

Humblement, je voudrais restituer mon larcin divin a M. le Ministre des Beaux-Arts. Hélas, il navigue a Lyon sur la mer violente des électeurs. M. Perrier fait la navette entre on né sait quel mystérieux village et Paris. M. Albert Sarraut est plus insaisissable que la plus grande des vedettes.

Alors, oppressée par le poids de ma faute, je vais remettre mon larcin, sous le sceau de la confession,

à Mgr Dubois. Mon rôle est terminé. Mais la destinée du dieu d’Angkor, qui vint en Occident sur des mers apaisées, né va-t-elle pas commencer seulement maintenant?

TITAYNA”

[“Yes, I stole it.

I had arrived in Indochina not on one of those steamers brimming with Corsican civil servants and Bovary wannabees convinced they were oh so adventurous by changing cabins at night, but by drowning some remnants of European prejudices in in the warm waters of Oceania for the longest time, and by despising Anglo-Saxon hypocrisy through stays in Australia or in the Philippines.

Now and here I am in Angkor, 630 kilometers from pathetic Saigon, fled thanks to the kindness of the Governor of Cochinchina who entrusted me with a car and a boy, thanks to the Resident of Cambodia who, in Pnom-Penh, gave me another car, and another boy.

Under the moonlight, Angkor is there now, dead mystery, buried in this other living mystery: the forest.

I leave the comfortable little low-rise hotel [24], where near me Americans were playing poker while drinking whysky. My steps resound in the warm night, and I go at their rhythm between the stone elephants, on the gigantic alley of shimmering flagstones as on either side, the sleeping ponds under the lotuses.

Alone in Angkor, at night. The vaults are filled with the cries of thousands of bats. The furtive movement of a monk animates a corner of shadow, and the hieratic silhouettes of Buddhas with downcast eyes stand out against shreds of milky sky. Successively, I crossed the three sacred enclosures, each time higher than Angkor Wat. Between its steep staircases, the choir of the temple rises, an empty tabernacle, towards the silent sky. I climb the high painful steps, as if man had never been able to conceive the idea of a God without Calvary. All around me, beyond the three sacred walls, each time lower, the monkeys of the forest call and answer each other like men.

Sitting on the disjointed slabs of a second-floor gallery, leaning against a pillar, I let my gaze be hypnotized by a stone Buddha, enigmatic like everything invented out of our anxiety. The moon, too white, cuts out sharp shadows, and in the play of its light, I seem to see opening towards me eyes closed to all misery.

What time is it ? Dawn is already throwing its golden stain on the purity of the night. The silent Buddha always converses with my departed soul, which with the day slowly rejoins me, curls up and falls asleep, while my rediscovered eyes no longer see before them anything but a stone statue, with a mossy grain, moving on contact like the flesh, with eyes closed on an absent thought, and whose mouth with hemmed lips seems to admit that the gods know the kiss.

This morning, I asked my guide: “- It’s easy, isn’t it, to take pieces from Angkor? “- Yes, it’s easy. But why don’t you buy? ” Buy pieces of Angkor! Alas! for relatively small sums, tourists, at Angkor, obtain the remains of sculptures… that “cannot, it seems, be used for the reconstruction of the city”. Isn’t this the best way to suggest that they take a piece chosen by them during their walks? Isn’t this systematically depreciating what is invaluable? And how surprised then by what I had been told in Japan and which I had refused to believe: Angkor will gradually end up in foreign museums all over the world.

Before reaching Indochina, I already knew the grain of old Cambodian sandstone softened by time, having caressed fragments that emerged from suitcases studded with labels, on ocean liners or in the halls of palaces. Between Manila and Hong Kong, an American diplomat had me admire a rather large stone from which was born, in low relief, a hallucinating tevada (sacred dancer). “I took it from your Cambodia, he told me… — Is it so easy? — I don’t know if it’s easy for the French… I heard people say that French journalists had been arrested. You must be watched, but we Americans are left alone!”

I went back to see my Buddha friend. An ancient fracture has separated his head from his body. He understands me and speaks to me. A project is born in me.

I also know what I wanted to know. Foreign tourists with easy money circulate freely in Angkor with purchased guides. They are not satisfied with taking away shards of stone. Without worrying about damage, they snatch from the monument what tempted them the most. For the rarest French people passing through with an independent mood and a solitary walk, la surveillance will be more suspicious and more hostile. “What good could come of a Parisian journalist?…” some colonial officials exaggeratedly think. If this civil servant prides himself on literature and has not been showered with laurels by the metropolis… the passing reporter has better behave himself.

Under the crushing midday sun, in the reverberation of the stones which make Angkor, in the hot hour, a daubesque [Dantesque?] inferno, I will see “my Buddha” again. I already say “my” Buddha, and it is with his consent. I know he will accompany me to the West with its barbaric civilization. In which purpose born of infinity? I don’t know. Will this journey of the Buddha from Angkor to Paris one day tell me of his mysterious destiny, or else, martyr, has he sacrificed himself so that His Temple may be saved from scattering, more to be feared than gentle death? in the smothering of mosses and vines?

I took the detached and docile head. Rolled up in a canvas jacket, it weighs on my arm. And with the heavy stone leaning on my hip, I went back down into the sun, towards the humans.

But, in reconnecting with this land of agitation, I put on the cloak of petty contingencies and realities.

- Hey boy, quickly, my car, my bill…

I jostle the Anamite boys, shake my boy, buckle up my bag, and here I am at the wheel. It’s five o’clock in the evening. Saigon is 630 kilometers away. I have to cross the rivers on ferries, change cars in Pnom-Penh.

In case I have been spotted, I must arrive at the Saigon quay before the opening of the telegraph office tomorrow morning. I start in a cloud of red dust. Miles. Behind me the forest has closed in on the dead city.

To cushion the shocks, I dressed “my Buddha” in my airplane helmet. The counter is at 100, 110… To the right and to the left, the rice fields are fleeing, shimmering. The night has fallen, thick and transparent at the same time, and I cross it like an arrow behind the cones of moving light from the headlights.

Stars fell on the road, it is the eyes of the night owls that suddenly rise up in front of us, hit the radiator or the windshield, fall back killed or remain hooked, bloody and ruffled. Already the panes of the lanterns are broken. I didn’t let go of the accelerator…100…110…Kilometres. (To be continued)

In front of us: a car. Pass it on the narrow road. Reach the ferry before it. Wake up the sleeping boys, who with difficulty moor the raft on which we are seated. Their narrow, bare torsos above the fabric that molds their hips light up with the flickering light of the lanterns. They are beautiful. Their rhythmic and silent movements make around the divinity that accompanies me a serious and religious winding. The water rustles like the rustling of dead leaves, the two banks have disappeared. And then again the land behind the curtain of night, and the speed whistling in the ears… Saigon. I get there with the day. At the dock, the big Messageries Maritimes liner awaits me, motionless. I enter it as one crosses a border. I slide in the corridors, down the stairs “prohibited to the public”. No police in the world “knows” a boat as well as I do. Empty-handed, and soul at peace, I returned to my cabin, fell asleep on my berth.

Knocks at my door. — What is this? — Police!

In pajamas, I went to open. A telegram had told me out, as I had expected. A French journalist, isn’t it… The chief of the Security was there with a search warrant, but also with all the courtesy and intelligence in the world. For the sake of conscience, he visited my luggage, empty, and my innocent cabin. “A piece of advice, he said to me kindly, beware of your visit to Marseille…“

At this moment, a stranger comes over. He asks me in the name of the Governor of Cochinchina not to go to the Government in the evening, as I was invited to.…Brrr! We fear compromises in our Third Republic! However, if Mr. Blanchard de Labrosse [3] only knew how fresh the soul of habitual criminals is!

On board, my Buddha return to my cabin before arriving in Singapore. My neighbors lock themselves up in their homes every day, and the whole passageway smells of roasted hazelnuts: but the high-pitched reverie distilled by my stone companion is of even better quality.

Ceylon, Aden, Djibouti, Port Said, Suez. Cairo. Marseilles. Like the god that he is, my Buddha passed gloriously among the men bowed before his invisible presence.

Paris. I fear a search! My Buddha, momentarily, will leave me. For fifteen

days, I hid it in the Louvre Museum. From there he made a turn to the Conciergerie. He wandered behind the scenes of the Institute, under the shadow of the Obelisk, watching Paris revolve around him…

Humbly, I would like to restore my divine larceny to the Minister of Fine Arts. Alas, he is sailing in Lyon on the violent sea of voters. Mr. Perrier shuttles between who knows what mysterious village and Paris. M. Albert Sarraut is more elusive than the greatest of stars.

So, oppressed by the weight of my fault, I am going to hand over my larceny, under the seal of confession, to Bishop Dubois. My role is over.

But won’t the destiny of the god of Angkor, who came to the West on peaceful seas, only begin now?

TITAYNA”

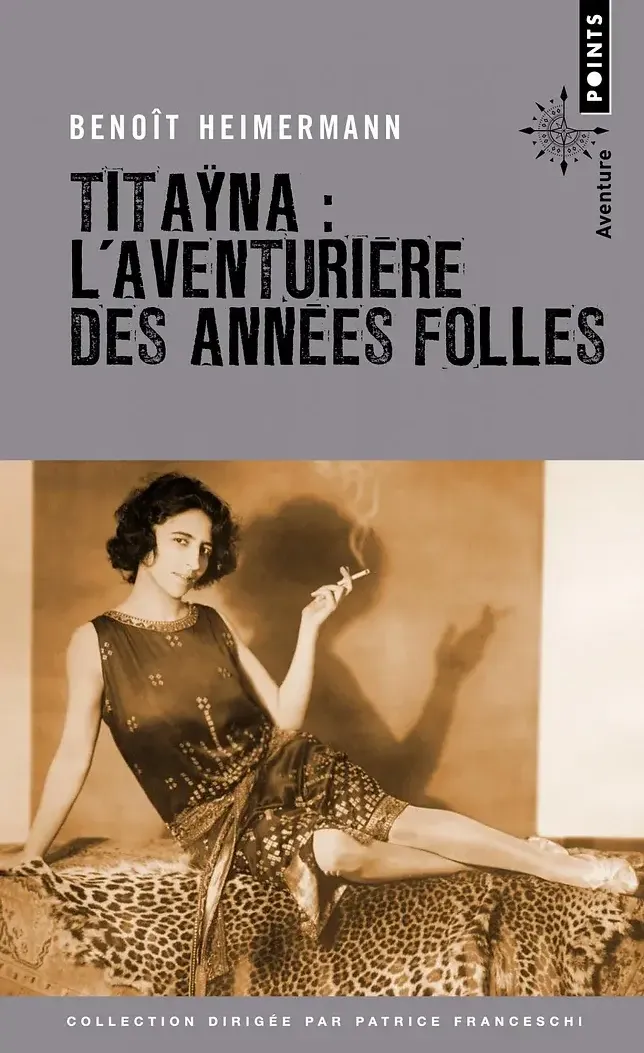

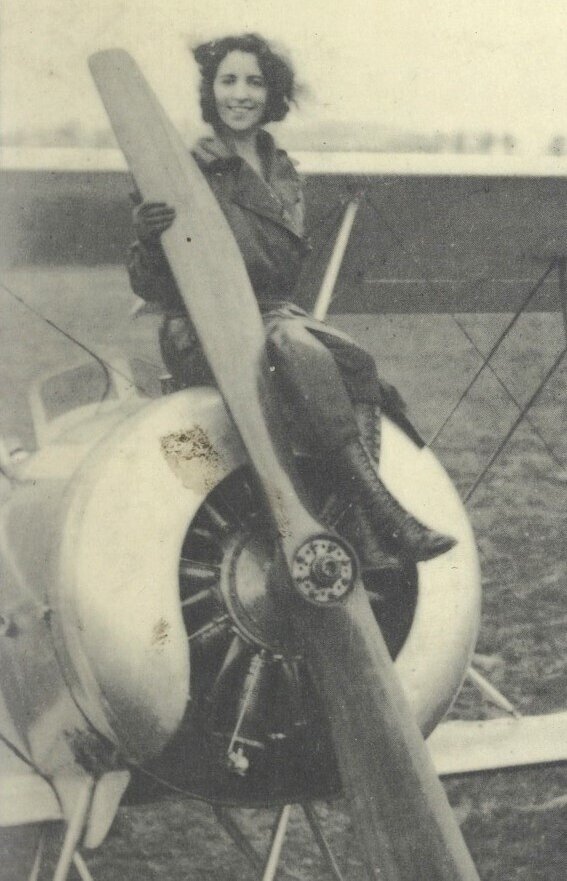

ADB Input: Titayna came to Angkor during her Tour du Monde (Round-the-World Trip) in 1927 – 1928, during which she experienced the full thrill of “Mes mains conduisent l’avion ou la voiture rapide. Mes genoux serrent le cheval docile, mes jambes s’équilibrent sur les skis allongés …Moderne ? Désespérement.” [My hands drive the airplane or the speedcar. My knees squeeze the compliant horse, my legs find balance on stretched-out skis…A modern woman? Desperately so.”] According to biographer Benoit Heimermann (Titayna, L’aventuriere des années folles, Flammarion, 1994 and 2011, 364 p), the journey went as follows: Marseille, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Panama, Tahiti, Tuamotu, îles Marquises, îles de la Société, Fidji, Nouvelles-Hébrides, Nouvelle-Calédonie, Sydney, Brisbane, Townsville, Nouvelle-Guinée, Manille, Nagasaki, Kyoto, Tokyo, Shanghai, Canton, Hong Kong, Saigon, Phnom Penh, Angkor, Singapour, Colombo, Aden, Djibouti, Port-Saïd, Marseille.

For Heimermann, the incident of the Angkor Buddha head was above all the random act of a budding author still unsecure of her social standing in Paris and of her literary credentials, not to mention a mere publicity stint: “Mon tour du monde est un incontestable succès. Le tirage dépasse les cinquante mille exemplaires, les ventes sont à la hauteur et la presse est, dans l’ensemble, séduite. Paul Chaveau, des Nouvelles littéraires, remarque que « Titayna paraît blasée, mais aussi avide et curieuse parce que sa vitalité domine ». Marc Chadourne, reporter comme elle, spécialiste de la Chine et de l’URSS, bouillonne : «Je suis en train de lire votre Tour du monde qui me plaît à fond. J’envie votre abondance, votre facilité, votre mobilité. Vous êtes une flamme, Titayna ! » André Demaison, qui deviendra bientôt un ami intime, surenchérit : « Votre chapitre sur le passage du canal de Panama est très supérieur à du Paul Morand. » Conscientes de voir la mayonnaise prendre, les éditions Querelle multiplient les opérations de promotion. Les libraires sont invités à accorder une place privilégiée aux« audacieuses aventures d’une femme seule à travers le monde» et à exposer du mieux qu’ils peuvent le compte rendu de son périple. Ces artifices né sont pas du goût de tous. À mi-chemin entre le reportage vécu et le roman exotique, Élisabeth n’a pas choisi son camp. Élisabeth né se formalise pas. À défaut d’être admise dans telle ou telle famille, elle se persuade qu’elle n’appartient à aucune. Sa soif de reconnaissance n’a d’égal que son goût de l’esbroufe. De peur d’être marginalisée, pis, d’être négligée, elle imagine des scénarios capables de relancer ses intérêts. Quitte à commettre quelques regrettables impairs. Le 1er avril 1928, la une du magazine Vu, créé quelques mois plus tôt par l’entreprenant Lucien Vogel, vend la mèche : « La tête d’un bouddha d’Angkor a été volée par un journaliste parisien. Pourquoi ? » […] L’affaire remonte à quelques mois. Au terme de son fameux tour du monde, alors qu’elle débarque pour une escale supplémentaire dans le port de la «lamentable Saigon», Élisabeth n’a qu’une obsession: rejoindre Angkor. La« forêt de pierre» est à la mode. Depuis le tout début du siècle, elle attire non seulement les missions exploratoires mais aussi des contingents de touristes toujours plus nombreux. Le récit léger du duc de Montpensier (La Ville au bois dormant) et les articles beaucoup plus documentés de l’architecte Henri Parmentier ont séduit plus d’un voyageur fortuné. À son tour, Élisabeth parcourt en automobile les six cent trente kilomètres qui séparent la capitale indochinoise du célèbre site archéologique. De toute évidence, elle n’ignore rien des mésaventures d’André Malraux survenues quelques années plus tôt. Mieux, elle persifle: «J’ai entendu dire que des soi-disant journalistes français avaient été arrêtés.» Et se réjouit secrètement de lui emboîter le pas.” [“My World Tour is an astounding success. The circulation exceeds fifty thousand copies, sales are up and the print press is, on the whole, seduced. Paul Chaveau, from Nouvelles littéraires, remarks that “Titayna seems jaded, but also eager and curious because her vitality dominates.” Marc Chadourne, a reporter like her, specialist in China and the USSR, sighs: “I’m reading your World Tour, which I really like. I envy your prolixity, your ease, your mobility. You are a flame, Titayna! ” André Demaison, who will soon become a close friend, outbids: “Your chapter on the passage of the Panama Canal is much superior to Paul Morand”. Surfing on the wave, the Querelle Editions are multiplying promotional operations. Booksellers are invited to give pride of place to the “daring adventures of a single woman around the world” and to expose the report as best they can. These artifices are not to everyone’s taste. [.…] Caught in between the direct reporting and the exotic novel, Elisabeth does not choose her ‘genre, and does not take offense. Failing to be admitted to this or that family, she convinces herself that she does not belong to any. His thirst for recognition is matched only by his taste for showing off. For fear of being marginalized, worse, of being neglected, she imagines scenarios capable of reviving her interests. Even if it means committing some regrettable oddities. On April 14, 1928, the cover of the magazine Vu, created a few months earlier by the enterprising Lucien Vogel, spilled the beans: “The head of a Buddha from Angkor was stolen by a Parisian journalist. For what?” […] The case goes back a few months. At the end of her famous world tour, as she disembarks for an additional stopover in the port of “pathetic Saigon”, Elisabeth has only one obsession: to reach Angkor. The “stone forest” is in fashion. Since the very beginning of the century, it has attracted not only the missions exploratory but also ever-increasing contingents of tourists. The light story of the Duke of Montpensier (La Ville au bois dormant) and the much more documented articles of the architect Henri Parmentier have seduced more than one wealthy traveler. In turn, Elisabeth travels by car the six hundred and thirty kilometers that separate the Indochinese capital from the famous archaeological site. Obviously, she is well aware of the misadventures of André Malraux that occurred a few years earlier. Better, she jeers: “I heard that so-called French journalists had been arrested.” And secretly rejoices to follow in his footsteps.”]

We do no see any connection between Tityana’s and Malraux’s ultimate motives. Moreover, the remark about ‘French journalists’ (obviously referring to Malraux) was made to her by an American traveler who had taken part in the looting of Angkor.

And what about the head?

As no one from the luminaries Titayna approched (including Mgr Dubois) apparently took interest in the displaced head, the connection Germaine Krull-André Malraux might be an avenue. After considering the photos of the time, this Buddha head shows similar traits with King Jayavarman VII’s heads, many of them ‘lifted’ or stolen from Angkor. The hairstyle and the enigmatic style point towards a Bayon-style sculpture, late Angkorian era.

[1] While the authors of the catalogue of the Centre Pompidou 2016 exhibition reproducing Man Ray’s photos of Tityana’s have omitted to notice the ‘A suivre’ (To Be Continued) mention in Vu n 5 publication, our digital version of the article is complete.

[2] The Bungalow or Hotel des Ruines.

[3] At the time of her visit to Indochina, the Commissaire-Général was Alexandre Varenne (1870−1947), a journalist himself, and a leader of the SFIO (French Labor Party). The Résident-Supérieur of Cambodia was Eugene Le Fol.

- Many thanks to Rémi Abad for pointing out the story to us.

- Further reading: ‘Nom de plume, Titaÿna’, Le Temps, 20 May 2016

- Further reading: Benoît Heimermann, Titaÿna, L’aventurière des années folles (Point Aventures, 2020, 360 p)

- Further reading: Yannick Le Marec, ‘Man Ray, Germaine Krull et Titaÿna : « j’ai volé une tête de Bouddha à Angkor »’, Par mots et par images Blog, Jan. 2023. In this essay, the author speculates that the stolen head might have been finally bought by…Malraux himself: “Victor Segalen aussi était oppressé par le vol, la décapitation à la hache d’une statue de Bouddha. Il écrivit une première version de sa nouvelle La Tête, accablant le héros de mille malheurs plus atroces les uns que les autres, nota son compagnon de voyage. La version finale fut plus gentillette, faisant resurgir le mythe des saints céphalophores nombreux dans sa Bretagne d’origine. La tête chinoise est partie dans la famille Gilbert de Voisins. Qu’est devenue celle d’Angkor ? Une autre photographie de Germaine Krull détenue par le Centre Pompidou (mais non visible actuellement) représente Titaÿna et sa tête de Bouddha avec l’avocat François Bedel devant la Conciergerie à Paris. Le titre curieux (sans doute postérieur au cliché), ‘Titaÿna avec une tête de bouddha d’Angkor issue de la collection André Malraux’, semble envisager une autre fin à l’histoire de cette tête volée, reliant de manière énigmatique le pillage de 1923 et celui de 1928, en laissant entendre que Malraux aurait acquis la sculpture de Titaÿna…”

Tags: French explorers, French literature, collaboration, art, looting, stolen antiquities, French colonialism, museology, restitution

About the Author

Titaÿna

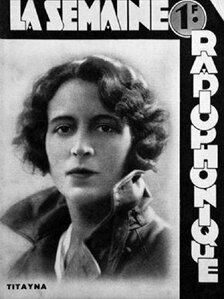

Titaÿna, pen-name of Elisabeth Sauvy or Sauvy-Tisseyre (22 Nov. 1897, Mas Richemont, Villeneuve-de-la-Raho, France — 13 Oct 1966, San Francisco, USA) was a French aviatress, reporter at large, photographer, known as the ‘Queen of Tout-Paris’ in the 1920s-1930s.

Early divorced from her first husband, the indefatigable traveler started to fly airplanes in her youth, and went to Japan to be part of the entourage of Japanese Princess Fusako Kitashirakawa. After surving a deadly car crash, she was granted a life pension which allowed to travel around the world, often flying her own airplane. Writing for prestigious French publications such as Vu, Voilà, L’Intransigeant, Paris-Soir, she interviewed worldwide leaders such as Mustafa Kemal, Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, Primo de Rivera or the head of the Corsican insurrection Romanetti.

Her fascination for Cambodia was not limited to her 1928 adventure in Angkor: in Marie Claire (9 July 1937, n 20, tp 30, he famous women’s magazine being only 4 months old), she published ‘Une histoire vraie par Titayna: Saramani, princesse et danseuse’, about Suzanne Meyer, the daughter of Royal Ballet dancer Saramani and author Roland Meyer, who was then a celebrated “exotic dancer“in France. Suzanne-Saramani was to die of privation in occupied Paris in 1942, at age 28.

With her wit and charm, Titayna (a nickname took after after a legendary Catalan female figure) was equalled to notorious reporters such as Pierre Mac Orlan (who penned the preface to her 1925 novel, La bete cabrée), Joseph Kessel, Blaise Cendrars or Albert Londres. Her work as a literary translator commanded author Jean Giono’s admiration. A teenager during World War I, she was to “remember in order to forget”: “1900 était né sur une bicyclette polka. Les voilettes de tulle enveloppaient de leur illusion les adultères d’avant guerre, et les orgues de barbarie donnaient aux provinciales le goût d’amours viennoises. /J’oublie./ Ma première communion eut pour cadre un grand parc de couvent, où durant neuf ans mon mysticisme révolté s’élevait vers les fleurs des vitraux et retombait avec elles sur les reposoirs aux parfums trop violents. /J’oublie./Il y eut une guerre qui bombarda la salle où je « séchais » sur une version de Tite-Live. Ma mère en blanc sentait l’hôpital, mon père fut tué en lisant du grec. J’avais un grand voile de crêpe. Le jazz-band commençait. De la jeunesse qui s’ignore. Un tourbillon grisant comme une noyade. Des soûleries d’exotisme, un voyage rapide en Europe ou en Afrique et plus lointain à Montparnasse. La mort frôlée comme une soeur aimée et contagieuse./J’oublie./ Le règne du simili : faux succès, faux amour, faux regrets, fausses haines./ J’oublie./” [“1900 was born on a polka bicycle. Tulle veils wrapped pre-war adulteries in illusion, and barrel organs gave the provincials the taste of Viennese dalliances. /I forget./ My first communion was set in a large convent park, where for nine years my rebellious mysticism rose towards the flowers of the stained glass windows and fell with them on the altars with too violent perfumes. /I forget./ Then came a war that bombed the room where I “dried off” on a version of Livy. My mother in white smelled like a hospital, my father was killed while reading Greek. I had a large crêpe veil. The jazz band was starting. Unaware youth. An exhilarating whirlwind like drowning. Exotic drunkenness, a quick trip to Europe or Africa and, even further, to Montparnasse. Death brushed past like a beloved and contagious sister./I forget./ The reign of imitation: false success, false love, false regrets, false hatreds./ I forget./”

After the death of brother Pierre Sauvy during the English attack on Mers El-Kébir in 1941, Titayana shifted her political involvment to collaborationist and antisemitic activism, leading to her arrest and after World War II in France. Self-exiled in San Francisco after her second husband’s death, she spent her remaining years with the Italian author and bookseller Giovanni Scopazzi.

Titayna’s writing belongs to the tradition of European travel writers loathing the “civilized world” and yet reluctant to embrace the Rousseauist myth of the ‘bon sauvage’. Libertarian, she writes also as a woman very much aware of the devastation of the patriarcal order. In Loin (1929, Flammarion, Paris), for instance, her potent diary of her travel to Oceania, she writes: “Quand les missionnaires y vinrent, ils firent un immense autodafé de pièces d’art primitif d’un intérêt certain, d’une valeur non moins certaine. Et c’est ce que j’appellerai une mauvaise opération commerciale. Puis, ils mirent les garçons d’un côté dans un internat, les filles d’un autre dans un couvent et séparés les uns des autres par un bras de mer. Comme filles et garçons étaient de beaux animaux, pour qui faire l’amour dans les bois

était plus que naturel, mais nécessaire, ce fut pour le moins une faute d’élevage […] Et l’Océanien, quand j’y songe, a plus de force que toutes les philosophies même chinoises, ils ont inventé ce

boomerang plus efficace qui fait que tout ce qui fait notre désespoir, ce que nous appelons l’amour ou bien les signes de croix, tout ce que nous jetons vers le ciel, ici fait un petit tour en l’air, revient, et l’on n’en parle plus.” [“When the missionaries came there, they made an immense auto-da-fé of pieces of primitive art of doubtless interest, of no less certain value. And that is what I would call a bad commercial operation. Then, they put the boys on one side in a boarding school, the girls on the other in a convent and separated from each other by an arm of the sea. As girls and boys were beautiful animals, for whom making love in the woods was not only natural, but necessary, it was at least a fault of breeding […] And the Oceanian, when I think about it, has more power than all the philosophies, even Chinese, they invented this boomerang more effective which makes everything that causes our despair, what we call love or else the signs of the cross, everything that we throw towards the sky, here takes a little turn in the air, comes back, and we don’t talk about it anymore.”]

Irreverent and snidely sensuous, she could title the second part of that same book ‘A l’ombré des jeunes filles enceintes’, a clearly un-Proustian image complete with the mysterious epigraph: “Ah ! beaux garçons inoccupés…”, and containing a ‘Plaidoyer pour l’anthropophagie’ (A Plea For Anthropophagy). She also noted: “L’Amérique est partie sur un idéal de pure littérature primaire : la Liberté. Vous pouvez en avoir les notions courantes dans tous les manuels. Pour assurer cette liberté, elle a instauré le travail, pour assurer ce travail, elle a tué cette Liberté. Ils en sont actuellement à travailler pour bien manger.” (p 12) [“America started from an ideal completely belonging to basic literature: Liberty. You can get all conventional versions of it in any manual. In order to guarantee that Liberty, America promoted work, and in order to strenghten work she killed that same Liberty. They have reached the point that they are now working only to stuff themselves.”].

Renowned French journalist Joseph Delteil would note in his diary on Dec 15, 1925 : “Vu Titaÿna ; un œil de gazelle dans un corps d’avion. Elle doit faire l’amour avec les palmiers.” [Met Titayna: gazelle eye and airplane body. Surely she makes love to the palm trees.]

Loin, cover (Flammarion, Paris, 1929, 122 p) [note the Star of David floating to the left of the illustration. In Loin, her growing judeophobia led her to write: “C’est une histoire juive que j’ai cueillie pour vous aux îles Gambier : Un jour, Isaac Salomon, qui était peut-être le Juif errant, après avoir franchi monts et plaines, traversa les Océans et débarqua dans les îles du Sud. Là, il vit plonger les jeunes hommes et comment ils trouvaient parfois une perle dans les nacres revendues aux Chinois. Il étudia leurs poids et leurs reflets, leur chair et leur forme et comment le soleil du soir les irise différemment. Mais il né s’installa pas acheteur sur place ; les îles basses semblent radeaux abandonnés et les Juifs préfèrent la fièvre des grandes cités au vent marin. Il repartit et se fit courtier en perles à Monaco, où près des salles de jeu, cette autre plongée, se trouvent des perles à vendre, plus souvent qu’au bord du lagon.” [“Here is a Jewish story that I picked up for you in the Gambier Islands: one day, Isaac Solomon, who was perhaps the Wandering Jew, after passing by mountains and plains, crossed the oceans and landed in the southern islands There he saw the young men diving and how they sometimes found a pearl in the mother-of-pearl later sold to the Chinese. He studied their weights and reflections, their flesh and their form and how the evening sun give them a different iridescence. But he did not settle there to buy the pearls on the spot — the low islands look like abandoned rafts and the Jews prefer the Big City fever to the sea breeze. He left and became a pearl broker in Monaco, where near the gambling halls — this other form of diving -, are pearls for sale more often than on the lagoon shore.”] (p 62) If this rather nasty aparte was an attempt to explain the origin of the name Solomon Islands, it is a total failure: sailors gave that name to the archipelago in reference to the mythical city of Ophir mentioned by King Solomon in the Bible, long after the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña had been the first European to visit these faraway islands in 1568.]

And a portrait by Man Ray after her return from Indochina and her World Tour in 1928:

See Francois-Xavier Bibert’s documented blog post on ‘Titayna, Gorgeous Adventuress, Reporter and Airplane Pilot’.