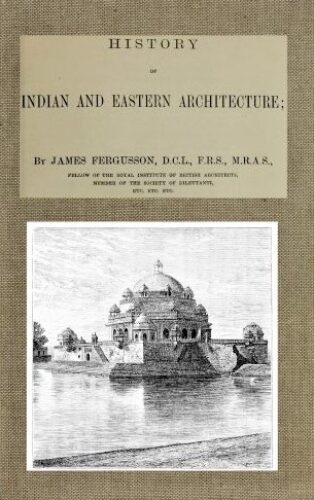

Cambodia (in History of Indian and Eastern Architecture)

by James Fergusson

Considerations on ancient Khmer temples in Cambodia by architecture historian James Fergusson (1808-1886)

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Book VIII (Further India), Chap. IV of History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, pp 663-685. John Murray, London

- Edition

- ADB Documents

- Published

- 1891

- Author

- James Fergusson

- Pages

- 25

- Language

- English

Apart from the main sources of his time (Bastian, Mouhot, Abel-Rémusat’s translation of Zhu Daguan…), the author relied on the photographs by John Thomson, a close friend of him, to develop his considerations about Angkor (then still called Nakhon Wat) and the Khmer architecture art. Of note:

- Khmer architecture as a unique, distinct art in Asia: ‘The temples are evidently very numerous, and all most elaborately adorned, and, it need hardly be added, very unlike anything we have met with in any part of India described in the previous chapters of this work. They certainly are neither Buddhist, Jaina, nor Hindu, in any sense in which we have hitherto understood these terms, and they as certainly are not residences or buildings used for any civil purposes. It is possible that, when we become acquainted with the ancient architecture of Yunan, or the provinces of Centraland Western China, we may get some hints as to their origin.’

- The French and British distinctive outlooks on the art of colonized countries: In a footnote, the author remarks: “Few things are more humiliating to an Englishman than to compare the intelligent interest and liberality the French display in these researches, contrasted with the stolid indifference and parsimony of the English in like matters. Had we exercised a tithe of the energy and intelligence in the investigation of Indian antiquities or history, during the 100 years we have possessed the country [India], that the French displayed in Egypt during their short occupation of the valley of the Nile, or now in Cambodia, which they do not possess at all, we should long ago have known all that can be known regarding that country. Something, it is true, has been done of late years to make up for past neglect.’

- The unique architectural techniques of the ancient Khmer civilization: ‘If the Cambodians were the only people who before the 13th century made such wheels as these, it is also probably true that their architects were the only ones who had sufficient mechanical skill to construct their roofs wholly of hewn stone, without the aid either of wood or concrete, and who could dovetail and join them so beautifully that they remain watertight and perfect after five centuries of neglect in a tropical climate. Nothing can exceed the skill and ingenuity with which the stones of the roofs are joggled and fitted into one another, unless it is the skill with which the joints of their plain walls are so polished and so evenly laid without cement of any kind. It is difficult to detect their joints even in a sun-picture, which generally reveals flaws not to be detected by the eye. Except in the works of the old pyramid-building Egyptians, I know of nothing to compare with it.’

- A feast for architects, art historians and ethnologists: ‘When we put all these things together, it is difficult to decide whether we ought most to admire the mechanical skill which the Cambodian architects displayed in construction or the largeness of conception and artistic merit which pervades every part of their designs. These alone ought to be more than sufficient to recommend their study to every architect. To the historian of art the wonder is to find temples with such a singular combination of styles in such a locality — Indian temples constructed with pillars almost purely classical in design, and ornamented with bas-reliefs so strangely Egyptian in character. To the ethnologist they are almost equally interesting, in consequence of the religion to which they are dedicated. Taken together, these circumstances render their complete investigation so important that it is hoped it will not now be long delayed.’

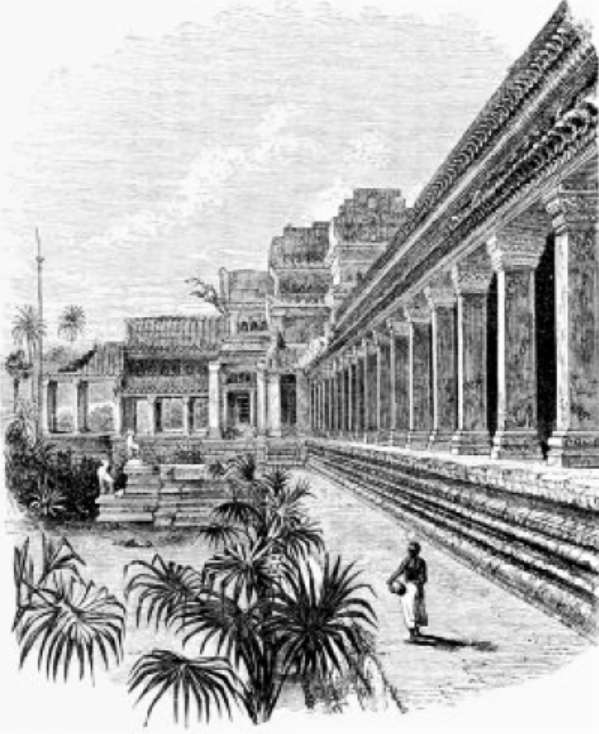

‘A view of Nakhon Wat, from a photograph by Mr. J. Thomson’

email hidden; JavaScript is required’

Tags: architecture, Khmer arts, photography, stone cutting

About the Author

James Fergusson

James Fergusson (22 Jan. 1808, Ayr, Scotland — 9 Jan. 1886, London, Great Britain) was a Scottish businessman and planter in India, and a self-taught architect whose fascination with the “True [or Pure, or Natural] Style” in Indian arts led him to write his monumental History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, first published in 1876, with a 1891 edition including several drawing plates made from his fellow countryman John Thomson’s photographs. Incidentally, Fergusson based his chapter on Cambodian architecture on the notes taken by Thomson and Kennedy during their visit to Angkor.

A fellow of the Royal Society, the Royal Institute of British Architects and a member of the Society of Dilettanti (1), he funded his Indianist studies with the income of his indigo plantation in Calcutta and Jessore between 1829 and 1934. Back to Europe, he settled in London, where he built an impressive Italianate home (very much in the ‘Renaissance man’ manner of the Enlightnement, developed his theory of ‘natural architecture’ — linked to the art of agriculture, based on ‘common sense’ –, and developed his library on India, Bengal and the Far East.

(1) The Society of Dilettanti was a rather informal British gentlemen’s club which has existed from 1742 to these days. On 14 April 1743 Horace Walpole provided a succinct summary of the group’s early reputation in a letter to Horace Mann, claiming that the Society of Dilettanti was ‘a club, for which the nominal qualification is having been in Italy, and the real one being drunk; the two chiefs are Lord Middlesex and Sir Francis Dashwood, who were seldom sober the whole time they were in Italy’ (Walpole, Corr., 18.211). Yet these merry and enlightened gentlemen quickly engaged in more serious endeavors, for instance sponsoring a first expedition to Greece which came back with the reference sum Antiquities of Athens. From then, the club of wealthy ‘dilletanti’ with a fondness for ancient arts and civilizations contributed to research publications and antiquities collecting, donating a significant part of its collections to the Victoria and Albert Museum in the 1910s.