Cambodian Quest

by Robert J. Casey

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, hardback

- Publisher

- Indianapolis, The Bobbs-Merrill Company

- Edition

- 1st edition

- Published

- 1931

- Author

- Robert J. Casey

- Pages

- 304

- Language

- English

The novel opens with a tracking shot on Nance Abbott (or Anne C. Abbott), a young, All-American young woman “dealing with the drudgery of news illustration and advertisement copy”, glancing over the San Francisco Bay from her little studio on Russian Hill. This character who could have been cut off the Mad Men series (three decades earlier) is shrouded with mystery from the start fades as we learn, thanks to a private investigator inquiring for a Miss Alysia Moore, “beautiful and blond but not without brains” [sic] at the overseas liner’s company, that she’s about to sail under this alias to Hong Kong and Saigon on the Pacific Queen [1]. In fact, she’ll be traveling on a cruising yacht, the Vandalia, invited by an older lady, Mrs Jerome Atwater, who claims to have been a close friend of Nance’s deceased mother.

During the long journey, Nance-Alysia is of course subjected to the openings of “pleasant and vapid” young men who can only glean from her that sails that “my business is simple, I am going up to Angkor to do some painting and I don’t wish to be caught by the rainy season.” But when she gets ready to disembark in Saigon, a French customs officer interviewing her onboard the yacht cryptically allows that he knows her real identity is Alysia Moore, and admonishes her to follow on to Singapore as “by being so, believe me, Mademoiselle, you may save your life.”

Puzzled but tenacious, she lands in Saigon, stumbling upon shady Americans, Jim Graves and Jake Garland, whom a young American woman (from Gary, Indiana), Lilac Hopkins, describes as contrabandists when they’re sitting on the terrace of the Continental Hotel — the place of choice of Graham’s Greene “ugly American” three decades later — and Lilac initiates her to the “Saigon drink by excellence”, Martell and Perrier [2]. She starts to haunt a Cholon night club cum opium den, Le Perroquet, and then several violent deaths happen right in front of her, including ‘a half-naked Chinaman’ right at her very doorstep.

All these murders are linked to a frantic quest for “the buried treasure of the Khmers at Angkor”, and the French inspector in charge of the investigation, the aptly named Monsieur Delaporte, finds the young American woman even more suspicious as she sets to the ruins of Angkor, although he agrees to arrange a car for her. One night at “a hotel on the water-front at Phnom Penh” [3], and onwards, the car dashing through the city as she silently reflects — as the author has done in his Four Faces of Shiva — , “Saigon has seemed a European city with Asiatics in its streets; Phnom Penh in the mists of the morning looked like an Asiatic city that accepted Occidental men and ideas only in sufferance.” [p 200].

The highway to Kompong Thom and then Siem Reap is seen “for miles under repair that seemed to have been unduly delayed,” with deep ruts and pitted surface, and at some point a knife is thrown to the driver’s head from the road side, and later — at the Kompong Thom ferry station — the mechanic reluctantly allows that before they left Saigon a man (Jim Graves) warned him that “something bad would happen to them” if they did drive to Angkor. Too late: as she’s about to cross the Stung Treng, she’s abducted, gagged and thrown in ‘a little car, a Citroen she judged.’ Kidnapped by Jim Garland and two Annamite acolytes, she goes through the jungle by car, then by foot, until they reach the “Khmer Lost City”, Sambor Prei Kuk [3].

Garland is already there, fumbling at “the end of a long black corridor” for the Khmer treasure (a theme already exploited by late 19th century French fiction writers such as Jules Lermina in Le Roi du Mal (King of Evil)). There is also a grey-headed, haggard white man wearing only a sampot, killed by Garland, who is later killed by Graves. After the murders, Graves calmly discloses to the young damsel that the former was Amos Carter, “a banker from Kansas City”, and the latter, Garland, “a deacon from Peace River, Iowa.” So, that Amos character had eloped long ago with the wife of a business partner, Gladys Derno, “once the most talented dancer on the American stage”, after looting his bank’s vault. Their freighter had wrecked in Halong Bay, and they had taken refuge in Saigon, along with his loot of emeralds, rubies, and other valuables. With no way to escape, and Gladys murdered by Garland — “who had been chief officer on Carter’s ship” -, the ruffian banker fled, and “went native, probably after getting a touch of the sun.”

Alysia Moore, whom everyone had presumed Nance Abbott was, wanted to retrieve the loot as an old friend of Gladys’. At the tomb of Lao-Tsing, Graves retrieves the precious gems he had hidden in the stone, gave them to the young Nance, and reveals the flowers he had placed there was for Gladys, “a wild creature but I loved her more than anything. She was my wife…” [p 293] But this is not the end: Jim Graves also discloses his real name is James Winchell Farris, and that he has fallen for Nance-Anne, who is now also madly in love with her heroe. They get married in Saigon and board the Vandalia, where we discover that Farris-Graves had used his auntie Emma Atwater for the whole ploy. The ‘treasure of the Khmers’ was nothing more than the jewels of Kansas City nouveaux riches.

About Sambor Prei Kuk សំបូរព្រៃគុហ៍ in 1927 – 9

In real life, the author had been intrigued by Sambor Prei Kuk សំបូរព្រៃគុហ៍ [or Isanapura ឦសានបុរៈ] since the site 30 km (19 mi) north of Kampong Thom, although already mentioned by Adhémard Leclère in the 1890s and later explored by EFEO in 1916, had just been more thoroughly documented and partly stabilized for the first time in 1927 – 1928 by archaeologist Victor Goloubew and architect Léon Fombertaux (1871−1936). Hearing news about their work, the author went there by himself during his trip to Cambodia in 1928.

Dating back to the Pre-Angkorian Chenla Kingdom (late 6th to 9th century), established by King Isanavarman I as central royal sanctuary and capital, Sambor Prei Kuk had until then remained relatively unknown to the French archaeologists. In Fombertaux’s 1936 obituary, Angkor Conservator Henri Marchal gave the following details:

En 1928, il fut chargé de continuer à Sambor-Prei Kuk les fouilles commencées l’année précédente par M. Goloubew dont les travaux avaient porté sur le groupe Sud. Léon Fombertaux acheva le dégagement du monument octogonal S‑8 et procéda à celui du sanctuaire S‑7. Il consolida le pràsàt S‑1 où M. Goloubew avait déjà travaillé et la tour d’entrée S‑2. Il poursuivit ensuite le dégagement du mur d’enceinte en briques orné de médaillons et entreprit celui de trois petits pràsàt entre les enceintes l et II de ce groupe. Dans l’un de ces édicules, il eut la bonne fortune de découvrir un fragment de mandapa circulaire en grès d’un type encore inconnu dans l’archéologie khmère. Après s’être acquitté de ces divers travaux avec sa conscience habituelle, il fut chargé de réparer un temple intéressant d’art khmèr primitif situé à proximité de la route coloniale 1 bis entre Phnom Pén et Kompong Thom, le Pràsàt Phum Pràsàt.

In 1928, he was tasked with continuing the excavations at Sambor-Prei Kuk Mr. Goloubew had started the previous year, then focusing on the southern group. Léon Fombertaux completed the excavation of the octagonal monument S‑8 and proceeded to clear the sanctuary S‑7. He consolidated the prasat S‑1, where Mr. Goloubew had already worked, and the entrance tower S‑2. He then continued clearing the brick enclosure wall adorned with medallions and undertook the excavation of three small prasat between enclosures I and II of this group. In one of these small structures, he had the good fortune to discover a fragment of a circular sandstone mandapa of a type previously unknown in Khmer archaeology. After completing these various tasks with his usual conscientiousness, he was tasked with repairing an interesting temple of early Khmer art located near Colonial Road 1 bis between Phnom Penh and Kompong Thom, the Prasat Phum Prasat. [Henri Marchal, “Léon Fombertaux (1871−1936)”, BEFEO 36, 1936, p. 650.]

Angkor Database Notes

[1] Formerly Star of Alaska, an ageing ocean rigger that would transport in 1934 a scientific mission on natural history].

[2] In Le Roi Lépreux, French novelist Pierre Benoit noted the composition of a mixed drink of choice among the French colonials in Cambodia at the time, the Kompong Thom, “one-third of Bengal mint liquor, one-third of gin, one-third of sake, sprinkled with nutmeg and ginger powders”.

[3] The novel suggests that the lost city was “north of Preah Khan” [of Kompong Svay], but this would be way too far from Kompong Thom.

Tags: American novels, American writers, novels, 1930s, literature, treasure, Sambor Prei Kuk, archaeology

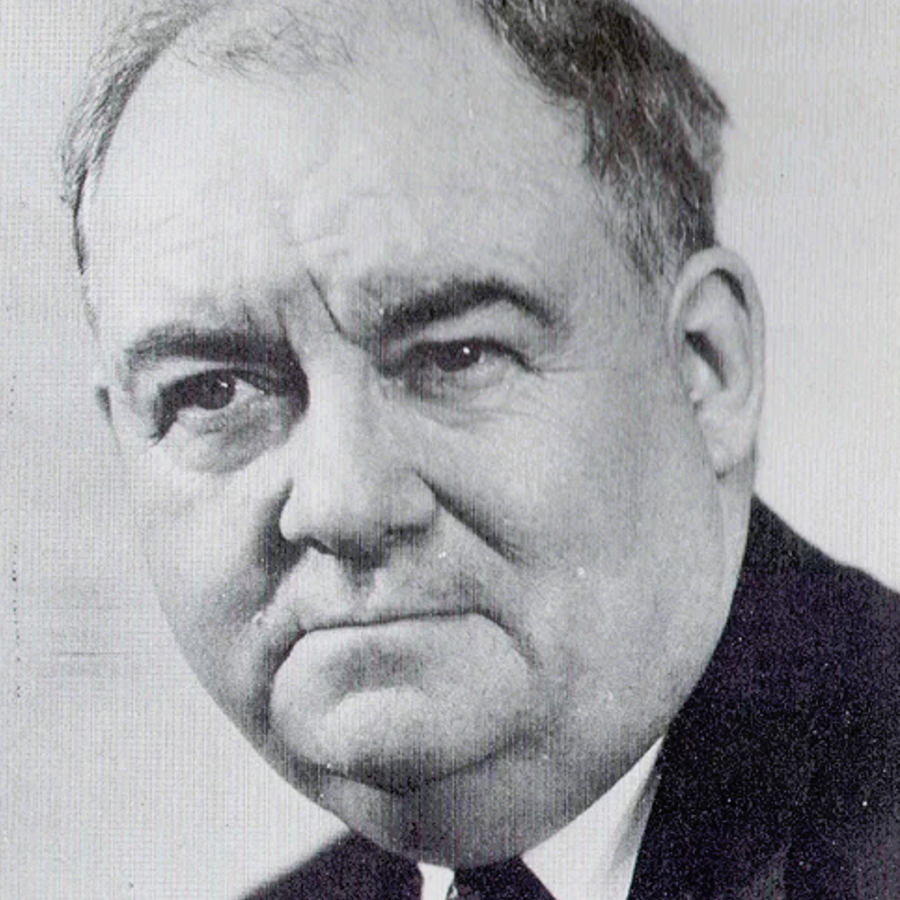

About the Author

Robert J. Casey

Robert Joseph ‘Bob’ Casey (14 March 1890, Beresford, South Dakota, USA – 5 Dec. 1962, Evanston, Illinois, USA) was a decorated combat veteran and Chicago-based newspaper correspondent and columnist who covered both World War I and II in Europe, Africa and the Pacific, a born story-teller of Irish ascent who traveled through Indochina and the Caribbean Islands in the 1920s and 1930s.

An enlisted artilleryman in Verdun and Meuse-Argonne in 1918, he published anonymously about his war experience in The Cannoneers Have Hairy Ears: A Diary of the Front Lines (1927), a realistic and vivid account he claimed to his name after being hired by the Chicago Daily News in 1920, in the columns of which he chronicled the Chicago gang wars and penned “slice of life” stories. In 1940, he covered the Blitz in London, the evacuation of Paris stormed by the IIId Reich’s army, and went to Hawaii and the Pacific immediately after the 7 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor — on assignment in Alaska, he rushed to Hawaii, arriving on 21 Dec. While the accuracy of his war reports was always praised, his colleague Quentin Reynolds described his style as “a strange combination of spot news, fantasy and feature material, full of the lighter overtones of the bizarre and the hilarious, which many recognize as the Casey touch.”

Dabbing in different literary genres — history, mystery, detective, gothic -, he wrote numerous novels or novelized essays between the two world conflicts, some inspired by his travels. Cambodia, in particular, which he visited in 1927 - with seeing Angkor as the main purpose of the trip -, was the inspiration for Four Faces of Shiva (1929) and Cambodian Quest (1931). In an interview given in Singapore at his return (‘Lost Cities of Cambodia: American Traveller Interviewed: A Journalist in the Jungle’, The Straits Times, 30 Dec. 1927, p 10), Casey gave an account displaying his Irish-American poetic streak.

He recounted that on the motorway from Saigon and Phnom Penh to Angkor, near Kompong Thom, he took “a rough road leading to an iron mine” to see “the ruins of a dead city” that had just been “found three years ago” [1924 [1]], “where so far as is known only five white men have ever been there before”. He had to stop his car “about nine miles away from the ruins which he wished to see”, got lost in his walk and ended up walking “twenty-six miles through rough country in nine hours, without nothing to eat or drink, blistered by tropical sun.” However, he had “found the lost city of Pra Khan” [Prasat Preah Khan of Kompong Svay ប្រាសាទព្រះខ័នកំពង់ស្វាយ], and even more, ” he made what was apparently a real new discovery in then shape of a vast, walled mass of masonsry with a moat, some distance away from Pra Khan […], an interesting problem therefore awaiting French archaeologists when they begin to study Pra Khan and the surrounding country.”

Since his Cambodian guide had refused to follow suit out of fear of tigers — “I didn’t see or hear any”, Casey allowed his interviewer, “but you know that smell of the cat-house in a zoo — I kept getting wafts of that as I went along.” Exhausted at some point, he fell asleep under a tree, and “when I awoke there were two Cambodians squatting on their heels in front of me, without a stitch of clothing on.” Unable to communicate with them, he let them walk with him until they reached a river.” About deadbeat by this time, I went to sleep again. I was awaken by a pulling at my feet and found two Cambodian ladies, also without clothing, trying to pull me into the river, while the men stood by and directed the operations.”

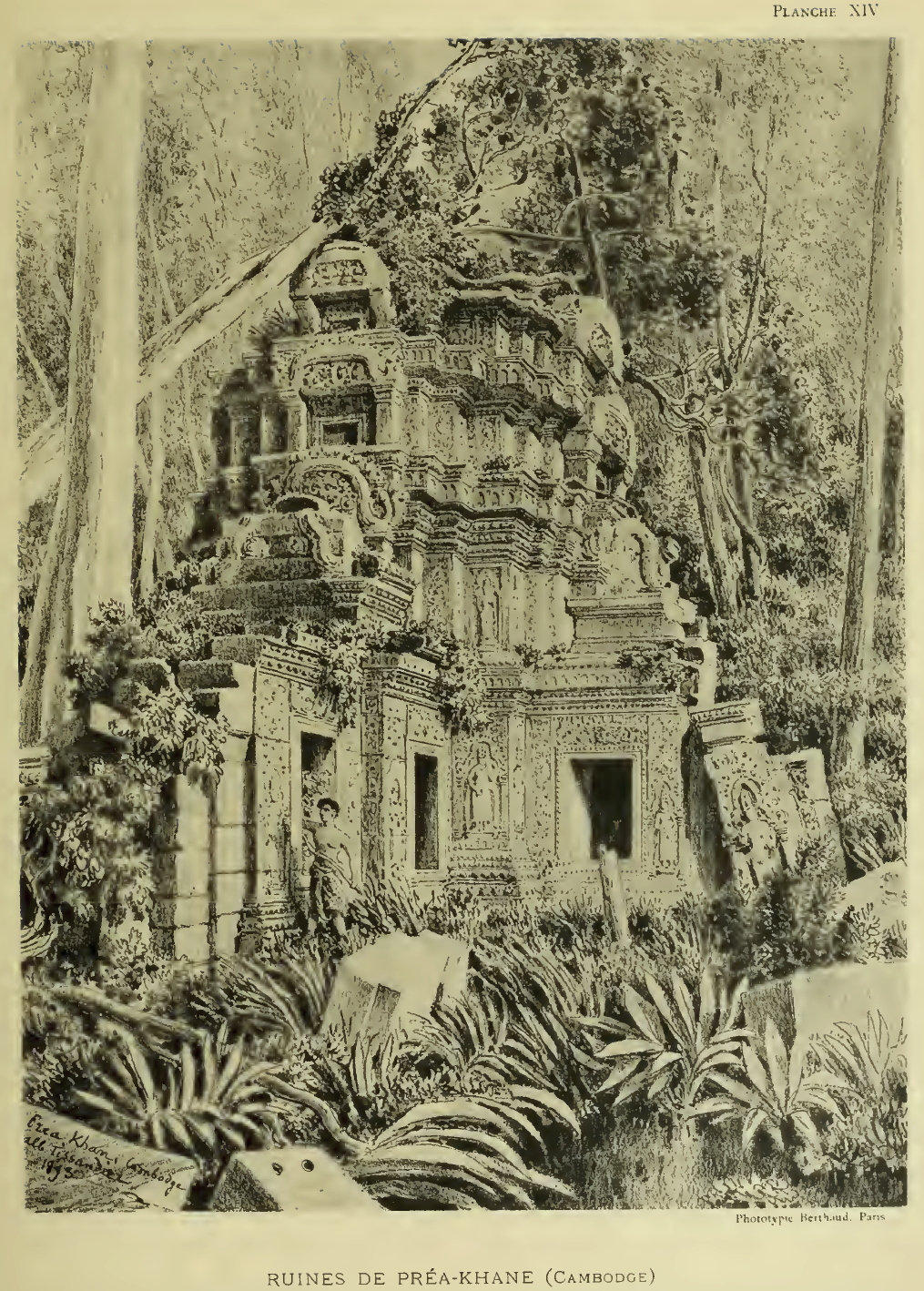

Part of the ruins of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay as seen by architect and Albert Tissandier in 1893 [plate 14 in Cambodge et Java, Ruines Khmères et Javanaises 1893 – 1894, Paris, G. Masson, 1896.].

Anyway, as he had “come out from the States especially to see Angkor,” Casey declared he had been “tremendously impressed with it,” adding: “I have seen most of the ruins of the world but I have seen nothing as grandiose as Angkor Wat, still in perfect condition, and the unknown fate of the highly civilized people who built it cannot but appeal to the imagination.” That was that for Angkor on that day, as the interviewer decided to abruptly switch the topic of conversation to “Big Bill” Thompson, the controversial mayor of Chicago, with Casey remarking that “during the war — before the U.S.A. went in — Mayor Thompson refused to invite [French General-Marshall] Joffre to Chicago on the ground that Chicago was the sixth German city in the world, which endeared him to the very large element in the city.”

Before his 1929 book, Casey had published an account of his visit to Angkor as “Four Faces of Siva: The Mystery of Angkor”, National Geographic 54/3, Sept. 1928: 302 – 332. [with photos by Emma L. Rose, SPI, and 27 natural color photographs by Jules Gervais-Courtellemont.] This was the second publication about Angkor in the prestigious American magazine launched in 1888, the first being Jacob E. Conner, “The forgotten ruins of Indo-China : the most profusely and richly carved group of buildings in the World”, National Geographic 23/3, March 1912:. 209 – 272.

Starting from I Can’t Forget: Experiences of a War Correspondent in WWII Europe (1941), however, the prolific author turned his attention to war memories, American railways sagas, collections of previously published articles, the city of Chicago and its people, and famous American inventors (of “everything including the kitchen sink!”). After the death of his first wife, Marie Driscoll, Robert J. Casey married in 1946 Hazel Mac Donald (1890−1971), one of the first American female journalists who briefly transitioned into screenwriting at Hollywood in the 1920s. He retired from the Daily News in 1947, keeping on his writing career with books and freelance publications. In 1955, he was named Press Veteran of the Year by the Chicago Press Veterans Association. A serious drinker and bon vivant, he liked to say of himself he was “big harp,” in reference both to his Irish ancestry and his portliness.

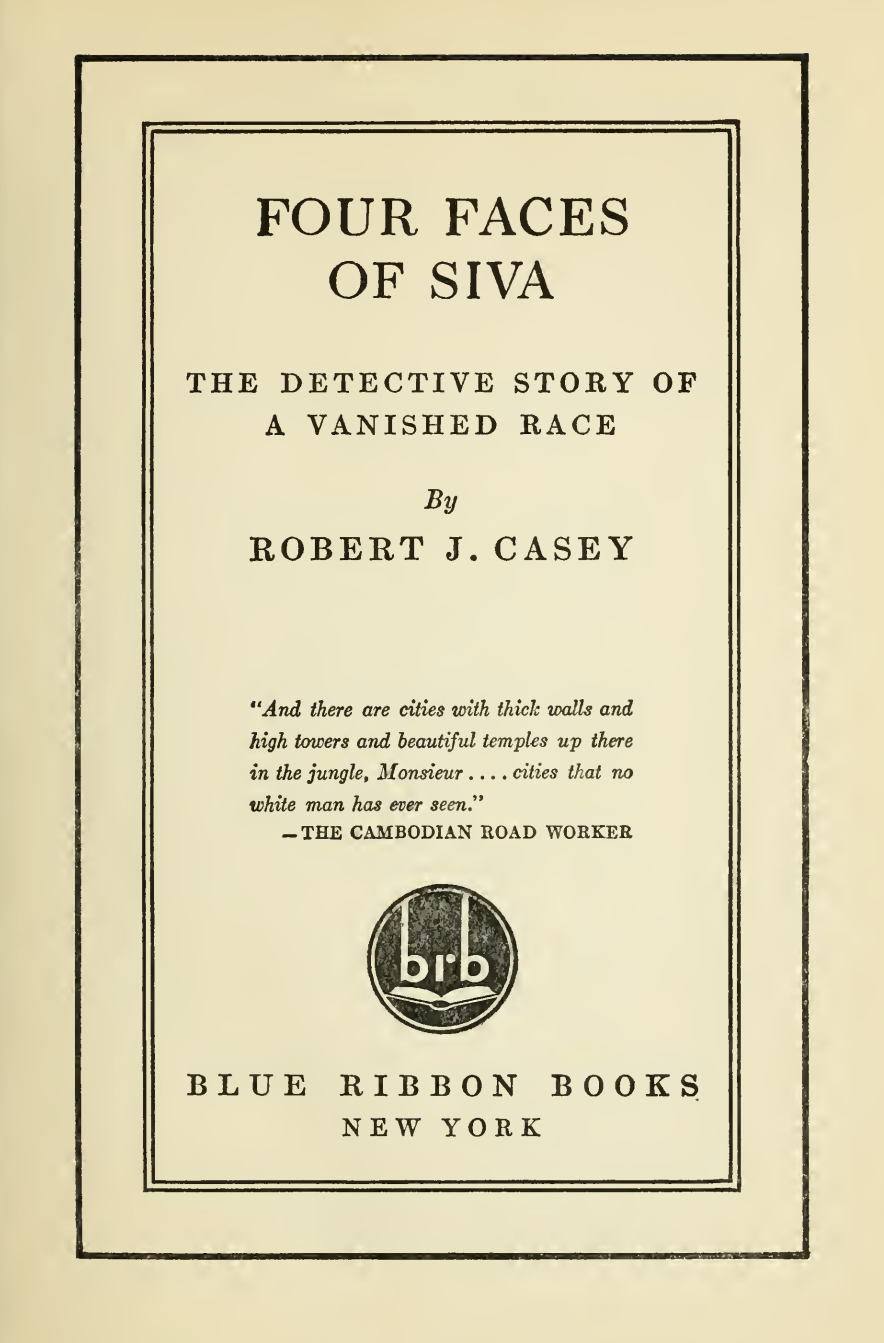

Book covers of Robert Casey’s two novels (first editions) related to Cambodia, 1) Four Faces of Shiva (1929), 2) Cambodian Quest (1931).

In a tribute piece published a few days after his death, famous screenwriter Ben Hecht, who had worked with him at the Daily News, wrote about his this about his friend’s wartime work:

There were many fine and mobile correspondents covering the war for our American press. But I don’t think any of them, not even Quentin Reynolds, ever achieved the Casey mileage, or ever stuck his nose into so many varied spots of confusion and danger. Up in planes, down in submarines, off on lone treks into dales and deserts, Bob Casey pumped more news out of the war and its aftermath. He reported battles, water spouts, sunsets, tribal dances, starving families, personalities, hysteria, incompetence and courage. And one more thing was usually in his reports — his own Chicago reporter version of all he beheld. It was a version that saw the comic, cock-eyed overtones of events, however big they were; and of people, however mighty their importance. [quoted by Marc Lancaster in Robert Casey’s Five Years of War, World War II on Deadline blog, March 2021]

Robert J. Casey’s personal papers were deposited by his widow, Hazel Mac Donald-Casey, at The Newberry Library — Modern Manuscripts and Archives Repository, Chicago, IL., USA.

[1] The Preah Khan architectural complex had been been documented by French archaeologists since 1873 [Louis Delaporte] and 1893 [Albert Tissandier]. Access to the site was still difficult at the time, and even if Victor Goloubew was to take a series of aerial photographs in 1934, the lack of historic sources from the time of its creation (11th century) explains the mystery surrounding it. The men and women in Adam’s and Eve’s costumes — loinclothes were not noticed by a sleepy Casey — might have been Kuy people, as the area was close to Phnom Dek [Iron Mountain], in Kuy territory.

Publications

[most of listed books between 1929 and 1962 were published by The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis, USA; whenever different, publishing houses are stated.]

- The Land of Haunted Castles, New York, The Century, 1921; repr. Forgotten Books, 2018, ISBN 13: 9781331056362.

- The Lost Kingdom Of Burgundy, New York, The Century, 1923.

- The Cannoneers Have Hairy Ears: A Diary of the Front Lines [published anonymously], 1927.

- Baghdad and Points East, London, Hutchinson, 1928; repr. Westphalia Press, 2014.

- “Four Faces of Siva: The Mystery of Angkor”, National Geographic 54/3, Sept. 1928: 302 – 332. [with photos by Emma L. Rose, Service Photographique de l’Indochine and 27 natural color photographs by Jules Gervais-Courtellemont.]

- Four Faces of Siva: The Detective Story of a Vanished Race, New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1929; repr. Simon Publications, 2001, 444 p., ISBN-13 :978 – 1931541404.

- The Secret of 37 Hardy Street, 1929; Spanish tr. El Secreto de Hardy Street, 37, Madrid, Novelas y Cuentos, 1946.

- The Voice Of The Lobster, 1930.

- The Secret Of The Bungalow, 1930.

- Easter Island, Home Of The Scornful Gods, 1930.

- Cambodian Quest: An Oriental Mystery, 1931, 304 p.

- Easter Island, Home Of The Scornful Gods, 1931.

- News Reel, 1932.

- Hot Ice, 1933.

- The Third Owl, 1934.

- I Can’t Forget: Experiences of a War Correspondent in WWII Europe, 1941.

- Torpedo Junction: With the Pacific fleet from Pearl Harbor to Midway, 1942.

- Such Interesting People [collection of newspaper articles], 1943.

- Battle Below: The War Of The Submarines, 1945; French tr. La guerre sous-marine au Pacifique, Artaud, 1949.

- [with Ernie Pyle & Colonel Robert L. Scott]100 Best True Stories of World War II, 1945.

by Robert J. Casey (Author), (Author) - This Is Where I Came In, 1945.

- More Interesting People [collection of newspaper articles], 1947.

- Chicago Medium Rare: When We Were Both Younger, 1948.

- [with W.A.S. Douglas] Pioneer Railroad: The Story of the Chicago and North Western System, Whittlesey, 1948.

- Mr. Clutch: The Story of George William Borg, 1948.

- [with W.A.S. Douglas] The Midwesterner. The story of Dwight H. Green, Wilcox & Follett Co.,1948.

- The Black Hills and Their Incredible Characters, 1949.

- [with W.A.S. Douglas] The World’s Biggest Doers: The Story of the Lions, Wilcox & Follett Co.,1949.

- The Texas Border And Some Borderliners, 1950.

- The Lackawanna story;: The first hundred years of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, 1951.

- [with Arthur Hillmann] Tomorrow’s Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1953.

- Everything and the Kitchen Sink, New York, Farrar-Strauss, 1955.

- Bob Casey’s Grand Slam: Anthology Of A Newsman’s Writings, 1962.