Four Faces of Siva - The Detective Story of a Vanished Race

by Robert J. Casey

Not a novel nor a purely journalistic work: the engaging take on Angkor and modern Cambodia around 1930 by a Chicago-based reporter and popular writer.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- New York, Blue Ribbon Books

- Published

- 1929

- Author

- Robert J. Casey

- Pages

- 373

- Language

- English

pdf 16.8 MB

Written after the author, an American journalist and mass-market novelist, had visited Phnom Penh and Angkor in 1927 – 8, this ‘detective story’ of the Khmer civilization opens with a dialogue on the banks of the Tonle Sap Bank between Chan the Fisherman and ‘The Pale One’, namely no other than explorer Henri Mouhot [1]. Back to the time when ‘The Khmers Walk into the Great Silences’, ‘The Detectives Arrive and The Tigers Depart’, to quote evocative chapter titles in the book. An opening mention of “the tiger smell that is in the breeze wandering lazily through the heat waves in the flats” is a direct reference to the author’s own journey as he recalled it in a 1928 interview with The Straits Times in Singapore, when he claimed he had sniffed the smell of a tiger as he was wandering alone in the jungle to find the ruins of Sambor Prei Kuk.

Mouhot was thus the first “detective” — or “necromancer”, as the author liked to call the researchers of Ancient Khmer civilization in this entertaining, well-informed travel book:

It is some sixty years now since the stunned eyes of Mouhot looked upon the magnificent heights of Angkor…Sixty years since the greatest detective story in the history of the world was laid out with its million stony clues to puzzle the elect. Today, with all its principal remains classified and ticketed, its inscriptions translated and its monuments lifted out of the jungle, Angkor is still the vast and silent mystery that it was in the beginning.

Archeology, already thrilled by the translation of the Rosetta stone and the unbelievable bit of detective work which led to the decipherment of the Syrian cuneiform inscriptions, turned its attention at once to this new field. The tigers and elephants which for centuries had made their home in the forests of the Mekong suddenly found that the jungle was becoming overpopulated with bearded and bespectacled gentlemen who wandered about without thought of danger or personal discomfort. They moved northward and left the Angkor district to the savants, and word by word the fragmentary history of the Khmers was pieced together.

The district then belonged to Siam. It was not ceded to France until 1907. But science declined to recognize any frontier. The galleries of Angkor Vat were cleared of the massed shrubbery. The inscriptions on the walls and pillars of Angkor Thom were copied and deciphered, and for sixty years learned men toiled here unceasingly to prove at length only what had been suspected from the first : That a highly intellectual people had built up in this valley a civilization, and that, however inconceivable experience might show such a thing to be, their marvelous culture had been sunk without a trace… [p 34 – 5]

[1] Interestingly, the novel 化境吴哥 [Transcendent Angkor] (2023) by Chinese author Jian Kong 孔见 opens with a dialogue on the junk moored at the mouth of the Siem Reap River to the Tonle Sap Lake between Henri Mouhot and an apparition of Zhou Daguan, the Chinese writer who visited Angkor in 1296 – 7.

The Fascination of Phnom Penh

Before Angkor, however, there is the capital city, reached from Singapore via Saigon, which the traveling writer has briefly described earlier. Even under the French Protectorate, what he feels here is the essence of Cambodia:

Seven-headed cobras guard the bridges. Spires of gold and stupas of stone rocket out of the greenery and into the vivid blue sky. Clean white buildings doze in the sun by the banks of the great river. And this is Pnom Penh, reliquary of the culture that was Angkor.

There is a fascination about Pnom Penh that one does not realize from descriptions of it given by casual travelers in the days when the Messageries Fluviales boats were the only transport to the North. It is a town of wide, well-shaded streets with a royal palace, a pretty park, and a vast and pictureful array of markets. But to a voyager who has come here after a long trip down the Chinese coast it is something else — it is a part of the country.

The cities which imagination always associates with the Orient are usually not Oriental at all. Shanghai, Hongkong, Manila, Saigon, Singapore — most of them are mere transplantations of Occidental communities with Occidental buildings, administration and customs. They are dwelling-places in exile for Caucasians, and, save for the apparently inconsistent spectacle of yellow people milling through their streets, are towns that one seems always to have known. Unless he goes inland some distance from the coast the tourist in the East sees nothing at all of the native life in the lands he visits. One port city is quite like another save for the accent in which one speaks pidgin-English. Shanghai and Hongkong are English; Manila, American; and Saigon, French. Pnom Penh, on the other hand, is Pnom Penh, and its parklike avenues are places of continuous surprise. [p 69 – 70]

The “Pont des Nagas” [Naga Bridge] on the street leading from the south to Wat Phnom, Phnom Penh. This often reproduced and never credited photograph was printed in the best possible way in Charles Robequain, L’Indochine française, Paris, 1930. To be attributed to the Service photocinématographique de l’Indochine, led by photographer René Tetard from 1920 to 1926, and later by Léon Busy. Around the time of Bob Casey’s visit, the photographers hired by the Service were working towards an expansive photo-exhibition for the Paris Exposition Coloniale, 1931.

The “Pont des Nagas” [Naga Bridge] on the street leading from the south to Wat Phnom, Phnom Penh. This often reproduced and never credited photograph was printed in the best possible way in Charles Robequain, L’Indochine française, Paris, 1930. To be attributed to the Service photocinématographique de l’Indochine, led by photographer René Tetard from 1920 to 1926, and later by Léon Busy. Around the time of Bob Casey’s visit, the photographers hired by the Service were working towards an expansive photo-exhibition for the Paris Exposition Coloniale, 1931.

[…] By day the capital is Cambodia in panorama. By night one lies awake listening to the heart-beat of tomtoms, the plaint of pipes and the weird melody of the bamboo xylophone as the spirit of the Khmers is conjured out of the dead ages by the necromancy of unseen dancers.

The principal building of Pnom Penh is the royal palace. It is not so much a palace as a group of palaces, temples and administration buildings. It is a modern erection as such things go in a region like this, but it gives one the impression of a close relationship with the antiquity of Cambodia. This is probably because the architectural motifs of Angkor, which have become most familiar to the Occidental world through pictures brought home by travelers, are to be found here in lavish use. The seven-headed cobra, for example, is seen here in its ancient service as a balustrade. Cambodian dancing-girls, who in the life are the twin sisters of the Apsaras in the Angkorean bas-reliefs, are reproduced in stone as caryatids upholding the glittering roofs.

For the rest the buildings are more Siamese than Khmer. They are all a glistening white with conventionalized snakes on their gables and gilded spires at their summits. The palaces are at their best when viewed from the outside. The throne-room has all the tawdry unreality of a stage setting seen too close at hand — an imitation magnificence of brass and gilt. It contains two thrones, one for the king, another for the gilded image of his late predecessor.

Elsewhere on the grounds is the royal treasurehouse in which is stored the famous jeweled sword of Cambodia. The sword is an elaborate affair the dull radiance of whose gems causes one to be politely doubtful of their authenticity. The treasure-house is filled with an odd mélange of trinkets ranging in value and interest from Napoleonic relics to the diamond-studded derby hat of the recent king.

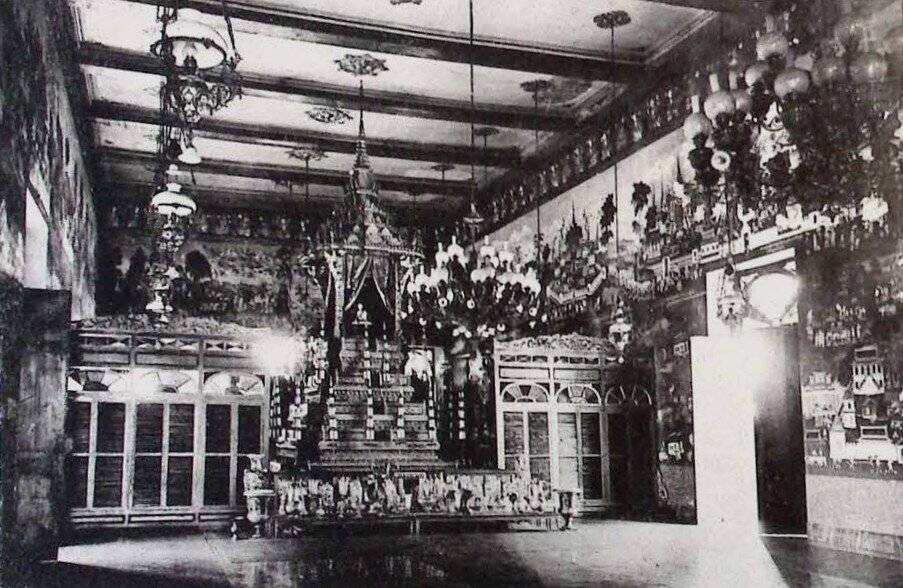

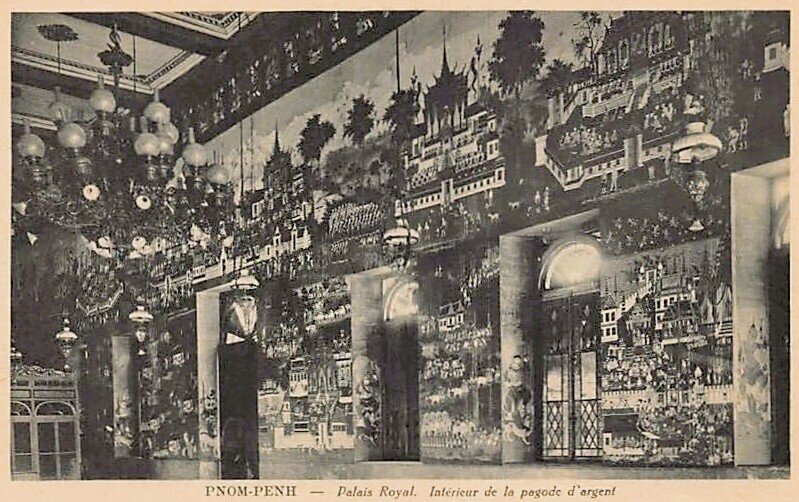

One temple on the grounds, visited only after much questing for keys and permits, contains a golden Buddha. The palace guide declared it to be of solid gold, which perhaps it is. He was similarly emphatic concerning the ornate floor whose tiles are supposed to be solid silver. One of the tiles, rubbed by the swinging of a badly hung door, showed an expanse of copper under the silver but what is the good of paying attention to a thing like that in the face of universal

evidence! [p 73]

[2] “Arya Deca” might be an alteration of “Āryāvarta” sk आर्यावर्त, ‘Land of the Noble Ones’, referring in Sanskrit texts to the areas of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and “Deccan” from Dakṣiṇā sk दक्षिणा), “south”, “right”, referring to the vast Deccan plateau at the uppermost southern part of the Indian subcontinent.

Inside the Silver Pagoda: 1) photo by Pierre Dieulefils, repr. in Ruines d’Angkor, Cambodge, 1909 [original edition kept at Angkor Database Library]. 2) photo by Fernand Nadal c. 1930.

The Foundation Legend

In the chapter ‘King Kambu and The Snake Lady’, the author gave an exhaustive version of the founding myth of Kambu, in this instance Kambu Svayambhuva, a former king in the land of Arya Deca [2], who had been married to “Mera, the beautiful foster daughter of Shiva”, and gets finally united to “the Princess of the Nagas” — nicknamed “the Snake Lady”:

Kambu, who apparently had journeyed under the sun before, showed no ill effects from the journey. He still seemed eager to meet the King of the Nagas and without further argument he entered the cave. He wandered down a long cool passage where crystals rose up from the stone floor and festooned the walls and hung in spear-points from the top of the gallery. All about him were hissing sounds but he could see nothing. The passage opened into a large chamber where the crystals were more numerous and made a dim light of their own. In a moment Kambu was surrounded by hissing serpents each of which lifted seven heads in a fan to look at him more closely. And the largest of the serpents spoke to him in a terrible voice. “What do you mean by invading the land of the Nagas?” he inquired. “What excuse have you to offer before you are put to death?” “I came to ask help,” replied Kambu simply.

“I am Kambu Svayambhuva and in my own land of the Arya Deca I was a king. Mera, the beautiful, foster daughter of Siva, the great god, was my wife. But I have been in great trouble. “Siva, the Destroyer, had one of his whims and blotted out the crops in my land and my people died. Even Mera was taken back into the bosom of Siva and I was left alone in a great desolation. So I wandered on toward the east, across high mountains and across desert plains, until I came here to the great river that runs through your forest, and there I found a magician named Dak with a talisman in his hand which is called Rice. I should like to stay here and use this talisman to rear up a nation of servants to the high gods, but if you do not will it you may kill me because I am unable to go farther.”

The King of the Nagas considered the matter for a long time. “Well,” he said, “for many centuries I have been put to the work of being god for this region and a thankless task it is, let me tell you. I’ve heard about you and your wife, and although Siva, the Destroyer, has no jurisdiction over immortals like us I have always heard him well spoken of. “In addition to that I have a daughter who saw you on your way here several days ago and made up her mind to marry you. All the rules indicate that you ought to be put to death but for the sake of peace in my own household I shall have to overlook your social error in coming here. We shall make a marriage for you. You as a mortal can not take our shape, but she will not mind taking yours and in her human appearance she is said to be even more beautiful than she is as a Naga. I shall look with interest on your experiment of building a nation. … As for your magician, bring him in. I shall find a new wife for him and reward him suitably for responding so readily to the charm my daughter put upon him. Usually she is quite second rate as a wonder worker.”

So Kambu married the Princess of the Nagas and settled down in the valley of the great river to make a new kingdom. His people were called the race of Kambuj as, the sons of Kambu, and eventually that name was distorted by the tongues of aliens into Cambodge or Cambodia. In its essentials that is the native legend of how the Angkorean kingdom got its start in the valley of the Mekong. Admitted that the dialogue may not be entirely accurate, admitted also that the existence of serpentine demigods called Nagas is open to serious question, none the less, there is a faint hint of historical significance in this fairy-tale. To begin with, it tells of how an Indian prince came to this corner of Asia after the blight of drought and famine had ravaged the land of Arya Deca as indeed it does to this very day. His name may or may not have been Kambu. It is just as likely that Cambodia took the name of one of its own myths as that it was so christened in honor of its first king. But whatever the authenticity of detail, the story indicates that ancient tradition in the valley of the Mekong ascribed the culture of the Khmers to an Indian origin. Kambu may have been one lone prince as described, or he may have been an allegorical type representing, in the figurative literature of the Khmers and their descendants, a great movement of people.

That the tradition of the Nagas was as firmly grounded in the people as the tenets of Brahmanism is evidenced in the motif of seven-headed cobras to be found in the balustrades of all their works. The “small-eyed people who worshiped snakes” were undoubtedly the aborigines of the region. The monuments about Angkor, the inscriptions over which archeologists have labored for sixty years, and the texts of old Cambodia preserved in Pnom Penh tend to show that the story of Kambu for all its resemblance to a reversed form of “Beauty and the Beast” must have come close to the truth. And why should not the history of the Khmers be told in a fairy-tale when Angkor itself is a myth that somehow became petrified? [p 96 – 100]

The common thread through the chapter is that the emblematic four-faced towers of Angkor represented Shiva in some of his multiple attributes, creator of life and death, of joy and sorrow, the Naṭarāja [“Supreme dancer and actor”] capable at the same time of mercilessly trampling and gracefully enthrancing the humans. This was the accepted interpretation when Casey visited Cambodia, later rejected by further historic analyzis.

Striking Dancing Girls on Strike?

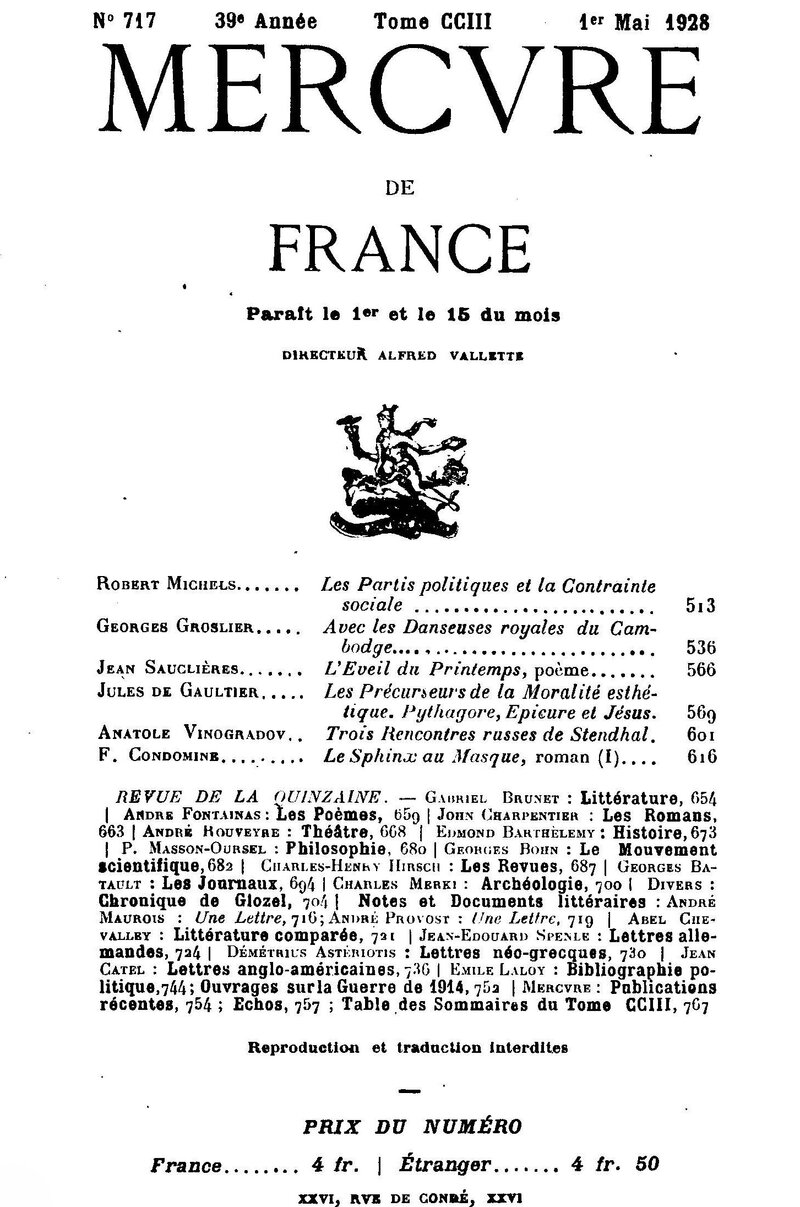

Two entire chapters [Moon Magic (Chap XII ) and The Dancing Girls (Chap XIII)] were entirely devoted to the Cambodian classical dance. The author had read a lot on the subject, and contrary to contemporary French writers did not find demeaning to quote another ‘girl’, Sappho Marchal, who had spent years studying the costumes and attitudes of the Apsaras. He might have even met with her, as she left Cambodia for France in 1928.

And all his musings start with attending a night performance at Angkor Wat. It was just a tourist show, apparently, yet the author carefully describes the reactions of the Khmer public and recounts in detail the theme of the dance, the story of Preah Samut and Neang Botsomali ព្រះសមុទ្ទ‑នាងប៊ុតសុមាលី:

It turned out to be a hazy, hypnotic thing, this dance… in its effect something like the No plays of Japan except that it was performed without a libretto and all the actors were girls. The weird lighting effects that made these performers one with the phantoms of the Khmers were furnished partly by the moon and partly by the hundred little boys who played unceasingly with their balsam torches.

The flame of the torches shifted and wavered and queer shadows climbed the walls of Angkor Vat. The resinous smoke, fragrant as incense, made a gauzy background in which the spectators became mere shadows. The xylophone ran trickling scales. The pipes squealed their unearthly melody. And the little ladies of the sculptured galleries came down the temple stairs.

In their odd costuming they seemed to be scarcely larger than the carved Apsaras whose resurrection they were attempting in this bit of necromancy. Their faces glowed corpse white with rice powder and their bare feet glittered with silvery rings. Tall conical crowns surmounted their close-bound hair. Their dress consisted of a long red skirt caught up between the legs and tied at the belt and a blue jacket starred with tinsel. Little upturned epaulets and metallic fangles at the hips designated the dancers who took male roles. Those who portrayed princesses and queens replaced the jacket with a scarf of silk about the breast and dispensed with the shoulder ornaments.

1) “Thespians in front of Angkor Wat”, a photograph taken by W. Robert Moore for the National Geographic c. 1934. Moore, an American journalist like Bob Casey, traveled the world photographying and writing travel features.

1) “Thespians in front of Angkor Wat”, a photograph taken by W. Robert Moore for the National Geographic c. 1934. Moore, an American journalist like Bob Casey, traveled the world photographying and writing travel features.

The dance, as in the No plays, was the enactment of a legend. It was not a dance at all as Occidentals understand dancing — merely a series of posturings, some of them pretty, some of them not, all of them accomplished only through remarkable muscular control. It was a startling thing to see these girls, their white faces as immobile and expressionless as masks, marching slowly through the drifting smoke and into the light of the torches — arms extended, bodies bent backward and feet advancing and descending with a movement almost imperceptible. […]

The chief skill of the dancers, however, lies in the control of the hands. The girls of the Angkor basreliefs are shown with an amazing series of hand positions…fingers curving back from the palm until they almost touch the wrist…arms in an arc that is explainable only on the supposition that the model of the Apsaras had double-jointed elbows. At a first glance the temple sculptures might be classed as caricatures, and a superficial critic might suspect that the artist had exaggerated detail merely to emphasize the Angkorean ideal of grace.

But these living Apsaras from Siem Reap whose only relationship to the sculptures was that of similarity of costume were able to do all these seemingly impossible tricks. Every movement of the friezes was accurately reproduced…The coryphees went even a bit farther than they might reasonably be required to go in maintaining the traditions of the old Hindu dance plays. They imitated something that was undoubtedly a defect in the bas-reliefs. The carvers of Angkor, like those of Egypt, were efficient in their picturing of all the human body except the feet. They never acquired the technique of showing a foot except in profile and so the ladies of the decoration are all box-ankled or pigeon-toed. [p 144 – 6]

[…] The modern dancers probably know nothing about art and its limitations but they are faithful to their models. If the stony ladies are pigeon-toed, then so also must be their sisters in the flesh, and the dance takes on the strange unreality of the puppet show…Somewhere up on the temple steps old women were crooning. The orchestra sat against the cobra balustrade, hidden by the crowd: a young man with a loose-headed drum — a betel-chewing elder with the xylophone — an ancient with a semicircle of cymbals suspended on a sort of disk — and a half-seen shadow who played the flute.

As the dance went on the little boys rested their torches on bamboo supports and sat back like ebony statuary except when compelled not infrequently to rise, remove their sketchy clothes and stamp out fires started by the resin sparks. Other children were clustered about on the backs of the little stone lions that guard the causeway or on the snaky lengths of the balustrade. Men smoking cigarettes and women down whose chins dripped the red hemorrhage of betel came and went from the shadows of the background as the flames staggered on the torches. And behind all rose the silhouette of Angkor against luminous cirrus clouds and the white face of the moon.

The dance had nothing seductive in it. The themes were all from Hindu mythology portrayed by a series of pictures rather than through any continuous movement. The music was monotonous but carried a melodic theme and was in a syncopated rhythm not at all difficult to follow. In native theaters where the companies have a large repertoire, performances sometimes start early in the morning and go on and on indefinitely. Any night at any hour in Pnom Penh one may hear the ripple of the xylophones and the muffled sobbing of the drums.

Here the dance starts, as it should, with the dramatic rising of the moon and it continues for about two hours. The pieces vary in character and number of principals as do the legends they portray.[…] Most of the dances are like that: kidnapings, chaste love scenes, fights with Yeacks, battles with bereft fathers, rescues of stolen maidens and triumphant entries…

The dance of Angkor came to an end as weird as its beginning. Fifteen girls who had been moving slowly but perceptibly suddenly stood like statues with their arms outstretched and their fingers turned back as if the charm of the moon that had taken them out of their niches in the galleries had lost its potency. And before one could make sure that they were not actually going back to their place in the friezes, the little boys scrambled to their feet, the torches were lifted up and the flaming procession started back through the black slot in the gate and across the moat. [p 149 – 50]

Two remarkable photographs of dancers from the Royal Ballet in Angkor Wat, 1920s, from an undated, uncredited photo album where the handwritten caption mentions they were “danseuses royales de Phnom Penh” (“Royal dancers from Phnom Penh”) [with thanks to Walter Koditek, who found the album in 2024 and kindly shared with Angkor Database.]

Two remarkable photographs of dancers from the Royal Ballet in Angkor Wat, 1920s, from an undated, uncredited photo album where the handwritten caption mentions they were “danseuses royales de Phnom Penh” (“Royal dancers from Phnom Penh”) [with thanks to Walter Koditek, who found the album in 2024 and kindly shared with Angkor Database.]

Two remarkable photographs of dancers from the Royal Ballet in Angkor Wat, 1920s, from an undated, uncredited photo album where the handwritten caption mentions they were “danseuses royales de Phnom Penh” (“Royal dancers from Phnom Penh”) [with thanks to Walter Koditek, who found the album in 2024 and kindly shared with Angkor Database.]

Casey had been intrigued by the crisis undergone by the Royal Ballet of Cambodia at the time, particularly in 1928, at the time of the coronation of King Sisowath Monivong and his own visit to Cambodia. It seems he directly talked about it with George Groslier and with Sappho Marchal. Henri Marchal’s daughter had just illustrated Prime Minister Chaufea Veang Thiounn’s book on Khmer dance, and was to leave Cambodia after spending here 23 years of her young life. The Chicago reporter instinctively valued her insights when most of French scholars specializing in Khmer studies looked down upon her artistic production.

Sappho Marchal, who made a considerable study of Cambodian theatricals, traces the entire ritual back to the India of a day before any Aryan movement took its way toward Indo-China. Monsieur Groslier proved a connection between the coryphees of the Khmers and those of old India by checking back, piece by piece, the costumes of the Cambodian troupes against those of friezes in temples of Madras and Bengal: double belts about the hips, the method of hinging double bracelets, the filigree work on the bracelets themselves. Marchal, after a study of the evidence presented by inscriptions and carvings in Angkor, says: “The dance was greatly honored during the Angkorean epoch. There were two varieties. One inscription tells us that the daughters of the nobles of the realm — even the royal princesses — took part in the dance. They played before many personages.

On the other hand the coryphees attached to the temple had a sacred character and their dance was not that of the theater. Moreover, their costume was always the same. The bust was nude and covered with a wealth of jewels and the sarong whose panels hung down on either side was caught up at the rear to allow greater freedom to the legs…There were then two sorts of dancers, the sacred coryphees of the temple and the actresses of the court — the women of the king and of the nobles. Something of the same sort is found in our day in India where there are to be found the devadasis and the nautehyn, these latter being the dancers of the rajahs. The inscriptions indicate that the dancing-girls chosen for the sacred service were recruited as in our times royal entertainers are recruited from among the most beautiful women of the realm, and proficient in singing and dancing. The earliest representations of them which have been found date from the eighth century. “The modern actresses, then, are the descendants of the temple girls. They inherit from the profane dancers nothing except a talent for playing the classic pieces.

“The Siamese after they had shaken off the yoke of the Khmer domination and as a result of conflicts which resulted from the sacking of Angkor, took over in part the civilization of the people they had conquered. The dancing-girls were subjected as a result of this to certain modifications. The cone of the ancient Khmer crown was heavy and low. At Angkor among the coiffures of the women which were so numerous, we find only two or three wearing a diadem with a single point. The ornament which fell from the middle of the cincture of the girls of the bas-reliefs is to be found today in the costume of birdwomen. M. Groslier informs us that ‘the velvet fringes and little disks of metal,’ which have been introduced into the costume, were brought to Siam by the Portuguese.

“The same author tells us also that the mantle of the dancing girls is of Khmer origin. It is the conventionalized form of the wrap which Cambodian women still wear about the breast and whose panel, lightly thrown, hangs over the back from one shoulder, the other shoulder remaining nude. It is to be regretted that this graceful fashion of wearing the shawl is tending more and more to lose favor. “These dances, the only living and breathing splendor of the Angkorean period which Cambodia has preserved, are unique. They are the most beautiful conception of an ancient art. They have all the soul, all the ideal, of the Cambodian people. They are exciting the admiration of artists who after having known and understood them for some time have all at once come to know the sum of beauty that is in them.” [p 155 – 6]

About the Royal Ballet proper, now:

The most important troupe of Cambodian dancers is in Pnom Penh and until a few months ago was an integral part of the royal menage. Travelers for generations have written about them and have agreed in classifying them as the living survivals of that civilization which expired hundreds of years ago on the banks of the Tonle Sap. Recently however, these custodians of the culture of the ancient Khmers became sufficiently modern to protest about their working conditions. They went on a strike and appealed to the French resident for a readjustment of their status. As a result they are no longer the dancers of the palace but a sort of state troupe whose performances are under the direction of the protectorate.

The girls of the Pnom Penh Company were recruited from all parts of the realm. It was considered a high honor to a family when one of its daughters was chosen to dance before the king. Socially it was an accomplishment, as an act of religion it was very meritorious, and financially it was profitable to an extent that depended more or less on the beauty and accomplishment of the girl. Training of the coryphees for the royal ballet was started with gymnastics at the age of eight years.

But it is likely that little girls brought down to the school at Pnom Penh had been undergoing treatment for promoting the flexibility of the fingers and elbows since they were able to walk. About Siem Reap today one sees mothers patiently bending back the fingers of their girl babies, massaging elbow joints and muscles in the hope that some day these children may be found worthy of a place in the ballet. Without flexibility and perfect muscular control it is impossible for the girls to make any headway with the intricate movements of the dance.

The royal dancers lived at the palace under the direction of the principal wife of the king. They were kept in seclusion although allowed to receive female visitors, and were considered a part of the harem. They were paid small sums for their performances but had as their chief reward the hope that one day they might become wives of the king. They knew that in old age they would find employment as dancing teachers or wardrobe mistresses. [p 157 – 8]

Hailing from Chicago, a center of unionist tradition, the author doesn’t find incongruous that these royal dancers, in their desire to leave a confined and constrained existence at the Palace, would go so far as to openly protest. There was certainly discontent at the time, as George Groslier himself (the most enlightened of the ‘Pale Ones’) carefully alluded to in his depiction of the life and artistic endeavor of the royal dancers before King Monivong’s accession to the throne. His allusion to a “strike” held by the dancers of the Royal Ballet was first spotted by Paul Cravath in his 1986 doctoral dissertation on Cambodian dance (later edited as Earth in Flower, DatASIA, 2007, p 140). The American scholar opined that Casey’s account — an “intriguing claim” — had been “highly influenced by the French of point of view”.

There is no mention in the book of the ‘parallel’ dance troupe launched at the time by a former dancer of the Cambodian Royal Ballet herself, Princess Say Sangvann អ្នកម្នាង សយ សង្វាន, the estranged wife of Prince Sisowath Vongskhat ស៊ីសុវត្ថិ វង្សខាត់ [King Monivong’s youngest brother], who was held as more compliant to the requirements of the French administration, in particular to make the Khmer classical dance more accessible to international tourists. Yet the description of the dance art scene in Cambodia at the start of the 1930s contrasts with the quite gloomy picture given by Groslier, to the point that one wonders whether the author is not describing a foregone vibrancy:

The Pnom Penh Company, however, is only one of a number in Cambodia. Auguste Pavie found theatrical troupes even in villages far back in the jungles. Sappho Marchal says that these troupes are generally made up of girls of the immediate neighborhood educated for their work more or less haphazard by some former member of the royal ballet. The form of the dance is rigidly adhered to. The costuming, while not so beautiful as that of the king’s company, is the same in design. She says: “The more the girls have occasion to dance, the more proficient they become in their art. This is doubtless the reason why the troupe of Siem Reap, so often called to give performances for visitors to Angkor, is one of the best. The life of these young women, accustomed to their work from infancy, is not entirely analogous to that of the girls of the palace at Pnom Penh. They live in the villages and are entirely free from the demands of the customary occupation of Cambodian women. Many of them are married. They have all the repertoire of the royal actresses with, often, more liberty of interpretation. “There are also itinerant troupes which give performances in the larger villages for periods the length of which depends entirely on the enthusiasm with which they are received. These companies are no different from the regional troupes.“

One might find a thought that here in Asia where woman has always been a creature of no consequence she appears as the sole preserver of the spirit of a mighty empire. For, when they drift through the moonlight and smoke on the terrace at Angkor, these girls are not women of Cambodia but the daughters of the Khmers. Angkor stirs in its grave and revives at their summons. The scenes as Prea Somut seizes his bride, and Piphok-Neak, King of the Nagas, rescues the child of the Princess Chantea, are not of to-day but of the time when the gilded elephants marched over the causeway and the ladies of the court rode to their devotions under scarlet umbrellas. The girls of Siem Reap and the vestals of the temples are sisters…And only the negligible calendar lies between them. [p 159 – 60].

1) A Cambodian royal dancer c. 1930, author and location unknown. 2) A royal dancer at the entrance of an inner gallery at Angkor Wat. That same photograph was included in Raymond Cogniat’s Danses d’Indochine (Paris, 1932), with the caption ‘Cambodian dancer costumed a servant’. The style and technique points to photographer Léon Busy. [both from C. Robequain, L’Indochine française, Paris, 1930].

1) A Cambodian royal dancer c. 1930, author and location unknown. 2) A royal dancer at the entrance of an inner gallery at Angkor Wat. That same photograph was included in Raymond Cogniat’s Danses d’Indochine (Paris, 1932), with the caption ‘Cambodian dancer costumed a servant’. The style and technique points to photographer Léon Busy. [both from C. Robequain, L’Indochine française, Paris, 1930].

1) A Cambodian royal dancer c. 1930, author and location unknown. 2) A royal dancer at the entrance of an inner gallery at Angkor Wat. That same photograph was included in Raymond Cogniat’s Danses d’Indochine (Paris, 1932), with the caption ‘Cambodian dancer costumed a servant’. The style and technique points to photographer Léon Busy. [both from C. Robequain, L’Indochine française, Paris, 1930].

A Speculative and Empathic Detective

Pressured by powerful neighbors, submitted to the French ‘protection’, was Cambodia then more cursed than blessed by its splendid past? The author summarized at the end some hypotheses for the demise of the Angkorian power, including, in typical American fashion, a Spartacus-like uprising against the powers-that-be :

Aymonier believes that a cultural migration into Cambodia out of India continued until the Moslem activities of the twelfth century left the mother country sorely wounded and closed the routes of travel through the Straits of Malacca. He sees in the decadence of Angkor a rising tide of native barbarism deprived of the restraining influences that had been maintained by a steady movement of colonists from Madras.

Certainly something happened to the culture of the Khmers during that dark night which begins after the year 1201. Sivaic Brahmanism ceased to be the state religion and Buddhist bonzes set up the statues of their master in the old temples. Up in the north the Thais, a coalition of races in which the Siamese were a principal factor, was gaining power, rebellious as it had always been against the Brahman gods and the castes which served them, and irked to the point of desperation by the government of a race, which, like Rome before its fall, maintained its domination only through the fear that its merciless might had set about it generations before. Over toward the east the Chams were preparing for revolt. And in Angkor was that lackadaisical atmosphere of nothing to do, whose existence is proved by the negative testimony of the unbuilt temples.

Artistic development ceased in Cambodia with the erection of Angkor Vat. It may have been that military reverses cut off the supply of slaves so essential to the massive constructions of the Khmers. It may have been that the artizans in their pride of accomplishment decided that they could do no better and laid down their tools. At any rate, the day of Angkor was done. The night was already advancing although the twilight lasted perhaps a hundred of years. [p 366 – 7]

[…] Certainly there were millions of slaves in Cambodia. Just as surely the educated people even amid a culture as fine as that of Angkor were only a small proportion of the total population. It is well within the probabilities that the slaves could have massacred the intelligentsia, and then, deprived of the brain that had directed their handiwork, their quick return to the primitive life of the jungle was an inevitable detail. […] Sunrise on Angkor Vat …The sky is hot now behind the towers. The mists are lifting from the lower galleries disclosing the silhouette of the temple as vaguely unreal as an image on a shadow screen. The ghosts are gone but their memory remains as the elephants come plodding across the causeway. The vastness of the pyramid seems to cover the horizon and for this moment, at least, the Khmers are alive again. A purple shadow, cast by one of the eastern towers, deepens the shade on the central spire. And it takes appropriately the shape of a question mark. No symbol — not even the linga of Siva, the Destroyer — could typify more clearly the soul of Angkor: Who were these people? [p 372 – 3]

Tags: Kambu, Mera, legends, Royal Palace, Phnom Penh Royal Palace, Phnom Penh, Siam, Khmer dance, dancers, 1920s, American travelers, American writers, women, 1930s

Associated Items

About the Author

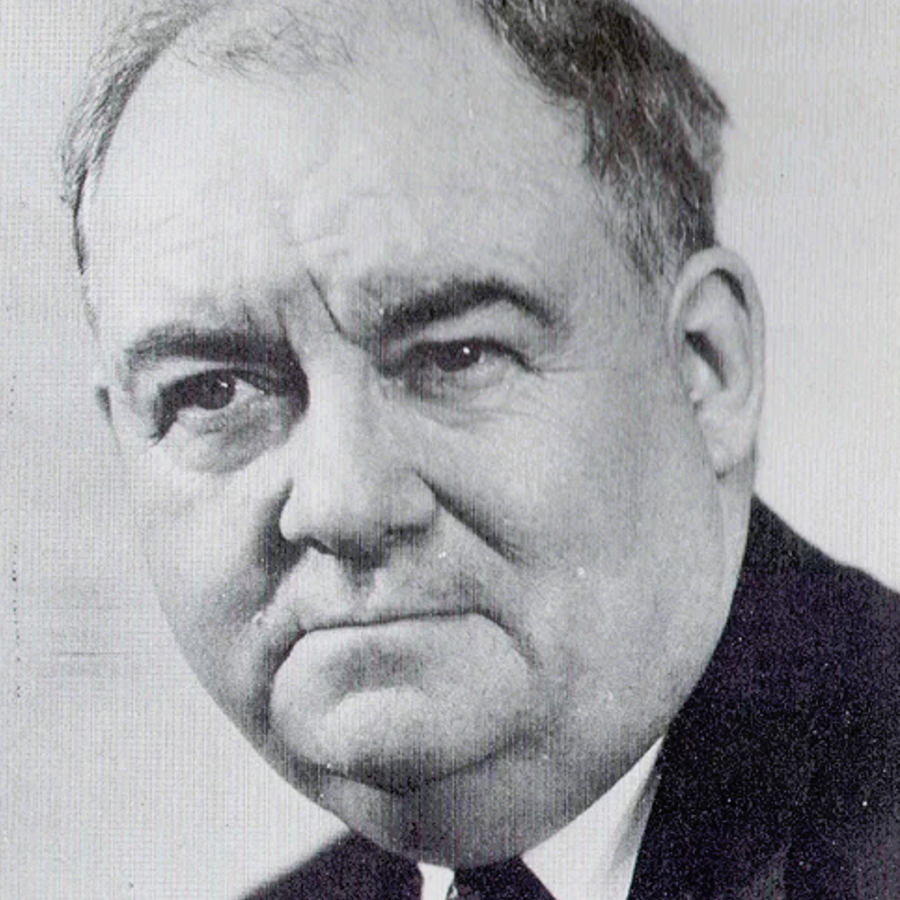

Robert J. Casey

Robert Joseph ‘Bob’ Casey (14 March 1890, Beresford, South Dakota, USA – 5 Dec. 1962, Evanston, Illinois, USA) was a decorated combat veteran and Chicago-based newspaper correspondent and columnist who covered both World War I and II in Europe, Africa and the Pacific, a born story-teller of Irish ascent who traveled through Indochina and the Caribbean Islands in the 1920s and 1930s.

An enlisted artilleryman in Verdun and Meuse-Argonne in 1918, he published anonymously about his war experience in The Cannoneers Have Hairy Ears: A Diary of the Front Lines (1927), a realistic and vivid account he claimed to his name after being hired by the Chicago Daily News in 1920, in the columns of which he chronicled the Chicago gang wars and penned “slice of life” stories. In 1940, he covered the Blitz in London, the evacuation of Paris stormed by the IIId Reich’s army, and went to Hawaii and the Pacific immediately after the 7 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor — on assignment in Alaska, he rushed to Hawaii, arriving on 21 Dec. While the accuracy of his war reports was always praised, his colleague Quentin Reynolds described his style as “a strange combination of spot news, fantasy and feature material, full of the lighter overtones of the bizarre and the hilarious, which many recognize as the Casey touch.”

Dabbing in different literary genres — history, mystery, detective, gothic -, he wrote numerous novels or novelized essays between the two world conflicts, some inspired by his travels. Cambodia, in particular, which he visited in 1927 - with seeing Angkor as the main purpose of the trip -, was the inspiration for Four Faces of Shiva (1929) and Cambodian Quest (1931). In an interview given in Singapore at his return (‘Lost Cities of Cambodia: American Traveller Interviewed: A Journalist in the Jungle’, The Straits Times, 30 Dec. 1927, p 10), Casey gave an account displaying his Irish-American poetic streak.

He recounted that on the motorway from Saigon and Phnom Penh to Angkor, near Kompong Thom, he took “a rough road leading to an iron mine” to see “the ruins of a dead city” that had just been “found three years ago” [1924 [1]], “where so far as is known only five white men have ever been there before”. He had to stop his car “about nine miles away from the ruins which he wished to see”, got lost in his walk and ended up walking “twenty-six miles through rough country in nine hours, without nothing to eat or drink, blistered by tropical sun.” However, he had “found the lost city of Pra Khan” [Prasat Preah Khan of Kompong Svay ប្រាសាទព្រះខ័នកំពង់ស្វាយ], and even more, ” he made what was apparently a real new discovery in then shape of a vast, walled mass of masonsry with a moat, some distance away from Pra Khan […], an interesting problem therefore awaiting French archaeologists when they begin to study Pra Khan and the surrounding country.”

Since his Cambodian guide had refused to follow suit out of fear of tigers — “I didn’t see or hear any”, Casey allowed his interviewer, “but you know that smell of the cat-house in a zoo — I kept getting wafts of that as I went along.” Exhausted at some point, he fell asleep under a tree, and “when I awoke there were two Cambodians squatting on their heels in front of me, without a stitch of clothing on.” Unable to communicate with them, he let them walk with him until they reached a river.” About deadbeat by this time, I went to sleep again. I was awaken by a pulling at my feet and found two Cambodian ladies, also without clothing, trying to pull me into the river, while the men stood by and directed the operations.”

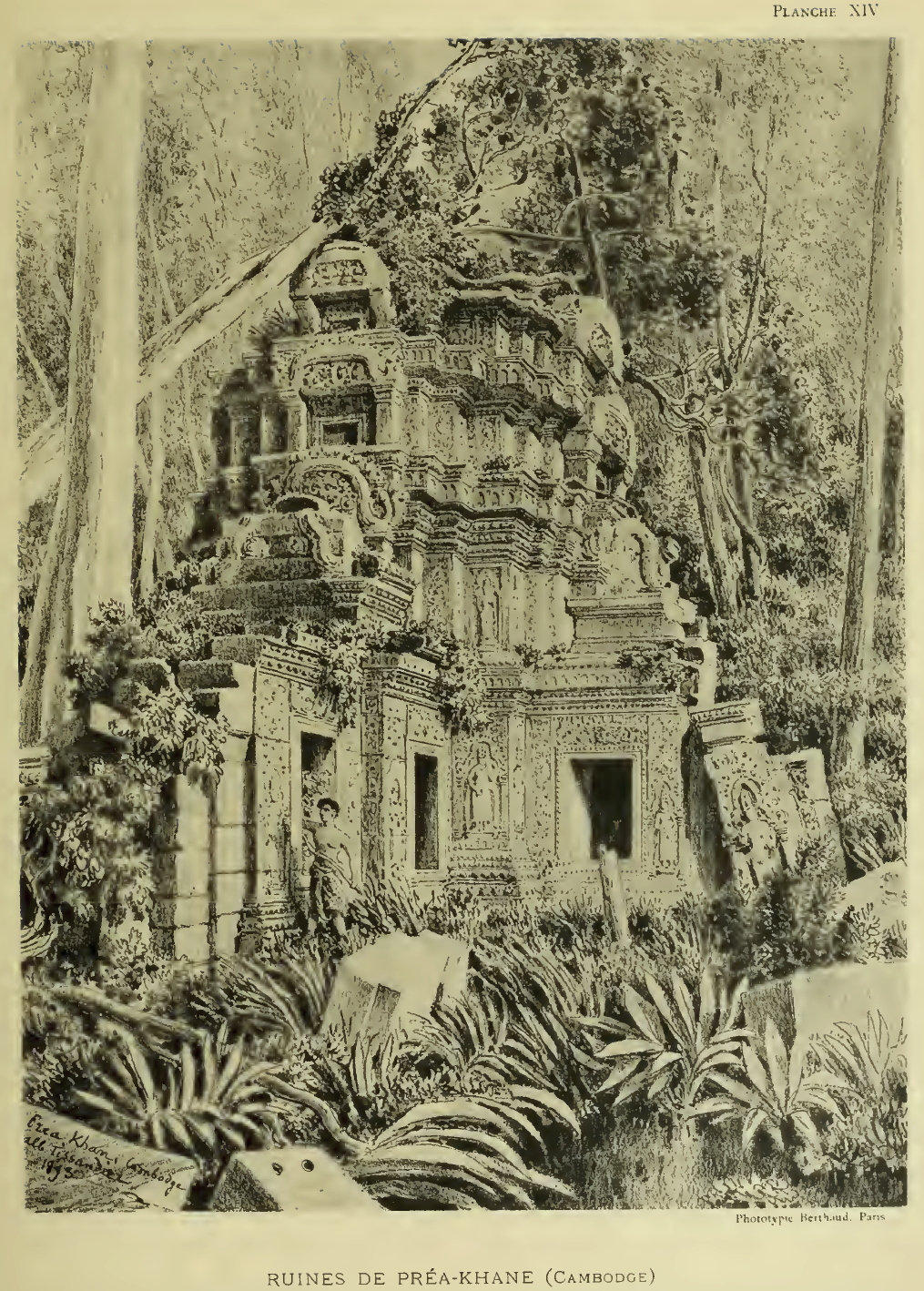

Part of the ruins of Preah Khan of Kompong Svay as seen by architect and Albert Tissandier in 1893 [plate 14 in Cambodge et Java, Ruines Khmères et Javanaises 1893 – 1894, Paris, G. Masson, 1896.].

Anyway, as he had “come out from the States especially to see Angkor,” Casey declared he had been “tremendously impressed with it,” adding: “I have seen most of the ruins of the world but I have seen nothing as grandiose as Angkor Wat, still in perfect condition, and the unknown fate of the highly civilized people who built it cannot but appeal to the imagination.” That was that for Angkor on that day, as the interviewer decided to abruptly switch the topic of conversation to “Big Bill” Thompson, the controversial mayor of Chicago, with Casey remarking that “during the war — before the U.S.A. went in — Mayor Thompson refused to invite [French General-Marshall] Joffre to Chicago on the ground that Chicago was the sixth German city in the world, which endeared him to the very large element in the city.”

Before his 1929 book, Casey had published an account of his visit to Angkor as “Four Faces of Siva: The Mystery of Angkor”, National Geographic 54/3, Sept. 1928: 302 – 332. [with photos by Emma L. Rose, SPI, and 27 natural color photographs by Jules Gervais-Courtellemont.] This was the second publication about Angkor in the prestigious American magazine launched in 1888, the first being Jacob E. Conner, “The forgotten ruins of Indo-China : the most profusely and richly carved group of buildings in the World”, National Geographic 23/3, March 1912:. 209 – 272.

Starting from I Can’t Forget: Experiences of a War Correspondent in WWII Europe (1941), however, the prolific author turned his attention to war memories, American railways sagas, collections of previously published articles, the city of Chicago and its people, and famous American inventors (of “everything including the kitchen sink!”). After the death of his first wife, Marie Driscoll, Robert J. Casey married in 1946 Hazel Mac Donald (1890−1971), one of the first American female journalists who briefly transitioned into screenwriting at Hollywood in the 1920s. He retired from the Daily News in 1947, keeping on his writing career with books and freelance publications. In 1955, he was named Press Veteran of the Year by the Chicago Press Veterans Association. A serious drinker and bon vivant, he liked to say of himself he was “big harp,” in reference both to his Irish ancestry and his portliness.

Book covers of Robert Casey’s two novels (first editions) related to Cambodia, 1) Four Faces of Shiva (1929), 2) Cambodian Quest (1931).

In a tribute piece published a few days after his death, famous screenwriter Ben Hecht, who had worked with him at the Daily News, wrote about his this about his friend’s wartime work:

There were many fine and mobile correspondents covering the war for our American press. But I don’t think any of them, not even Quentin Reynolds, ever achieved the Casey mileage, or ever stuck his nose into so many varied spots of confusion and danger. Up in planes, down in submarines, off on lone treks into dales and deserts, Bob Casey pumped more news out of the war and its aftermath. He reported battles, water spouts, sunsets, tribal dances, starving families, personalities, hysteria, incompetence and courage. And one more thing was usually in his reports — his own Chicago reporter version of all he beheld. It was a version that saw the comic, cock-eyed overtones of events, however big they were; and of people, however mighty their importance. [quoted by Marc Lancaster in Robert Casey’s Five Years of War, World War II on Deadline blog, March 2021]

Robert J. Casey’s personal papers were deposited by his widow, Hazel Mac Donald-Casey, at The Newberry Library — Modern Manuscripts and Archives Repository, Chicago, IL., USA.

[1] The Preah Khan architectural complex had been been documented by French archaeologists since 1873 [Louis Delaporte] and 1893 [Albert Tissandier]. Access to the site was still difficult at the time, and even if Victor Goloubew was to take a series of aerial photographs in 1934, the lack of historic sources from the time of its creation (11th century) explains the mystery surrounding it. The men and women in Adam’s and Eve’s costumes — loinclothes were not noticed by a sleepy Casey — might have been Kuy people, as the area was close to Phnom Dek [Iron Mountain], in Kuy territory.

Publications

[most of listed books between 1929 and 1962 were published by The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis, USA; whenever different, publishing houses are stated.]

- The Land of Haunted Castles, New York, The Century, 1921; repr. Forgotten Books, 2018, ISBN 13: 9781331056362.

- The Lost Kingdom Of Burgundy, New York, The Century, 1923.

- The Cannoneers Have Hairy Ears: A Diary of the Front Lines [published anonymously], 1927.

- Baghdad and Points East, London, Hutchinson, 1928; repr. Westphalia Press, 2014.

- “Four Faces of Siva: The Mystery of Angkor”, National Geographic 54/3, Sept. 1928: 302 – 332. [with photos by Emma L. Rose, Service Photographique de l’Indochine and 27 natural color photographs by Jules Gervais-Courtellemont.]

- Four Faces of Siva: The Detective Story of a Vanished Race, New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1929; repr. Simon Publications, 2001, 444 p., ISBN-13 :978 – 1931541404.

- The Secret of 37 Hardy Street, 1929; Spanish tr. El Secreto de Hardy Street, 37, Madrid, Novelas y Cuentos, 1946.

- The Voice Of The Lobster, 1930.

- The Secret Of The Bungalow, 1930.

- Easter Island, Home Of The Scornful Gods, 1930.

- Cambodian Quest: An Oriental Mystery, 1931, 304 p.

- Easter Island, Home Of The Scornful Gods, 1931.

- News Reel, 1932.

- Hot Ice, 1933.

- The Third Owl, 1934.

- I Can’t Forget: Experiences of a War Correspondent in WWII Europe, 1941.

- Torpedo Junction: With the Pacific fleet from Pearl Harbor to Midway, 1942.

- Such Interesting People [collection of newspaper articles], 1943.

- Battle Below: The War Of The Submarines, 1945; French tr. La guerre sous-marine au Pacifique, Artaud, 1949.

- [with Ernie Pyle & Colonel Robert L. Scott]100 Best True Stories of World War II, 1945.

by Robert J. Casey (Author), (Author) - This Is Where I Came In, 1945.

- More Interesting People [collection of newspaper articles], 1947.

- Chicago Medium Rare: When We Were Both Younger, 1948.

- [with W.A.S. Douglas] Pioneer Railroad: The Story of the Chicago and North Western System, Whittlesey, 1948.

- Mr. Clutch: The Story of George William Borg, 1948.

- [with W.A.S. Douglas] The Midwesterner. The story of Dwight H. Green, Wilcox & Follett Co.,1948.

- The Black Hills and Their Incredible Characters, 1949.

- [with W.A.S. Douglas] The World’s Biggest Doers: The Story of the Lions, Wilcox & Follett Co.,1949.

- The Texas Border And Some Borderliners, 1950.

- The Lackawanna story;: The first hundred years of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, 1951.

- [with Arthur Hillmann] Tomorrow’s Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1953.

- Everything and the Kitchen Sink, New York, Farrar-Strauss, 1955.

- Bob Casey’s Grand Slam: Anthology Of A Newsman’s Writings, 1962.