ល្ខោនពោលស្រី Lakhoan Porl Srei [Female Speak-Theater]

by Neak Chen

The rebirth of an ancient theater-dance form in the Kandal Province after the somber years of civil war.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Amrita Performing Arts & Cambodia Linc Organization, Phnom Penh

- Edition

- digital version by ADB

- Published

- 2007

- Author

- Neak Chen

- Pages

- 146

- ISBN

- 99950-80-0-3

- Language

- Khmer

pdf 37.8 MB

In spite of the civil war, villagers kept ancestral art forms alive, and in post-war Cambodia researchers unearthed a written document allowing to better understand the origin and codes of a form of “spoken theater and dance” dating back to the 17th century: that is the fascinating story told in this book, the story of ល្ខោនពោលស្រី Lakhoan Porl (or Puol) Srei.

While preparing this document, researcher and dancer Sok Nalys made the following comments: “Lakhoan here refers to “dramatic performances” or “performances to illustrate a story”, meaning that this art form is mostly the performance of any story [រឿង rueng, in Khmer] , or of any scene extracted from a longer story. For example, Lakhoan Porl Srei repertoire includes the stories of Preah Chinvong, Lin Thong, Preah Sothoun Neang Keo Monora… What makes this book precious is the coincidence in the discovery of the old manuscript, which triggered the revival of this waiting-for-lost art form, the sacredness of the art form in a style of villagers, and the way the author poured all the information regarding techniques that allowed the next generation to read and have enough information to recreate performance afterwards.”

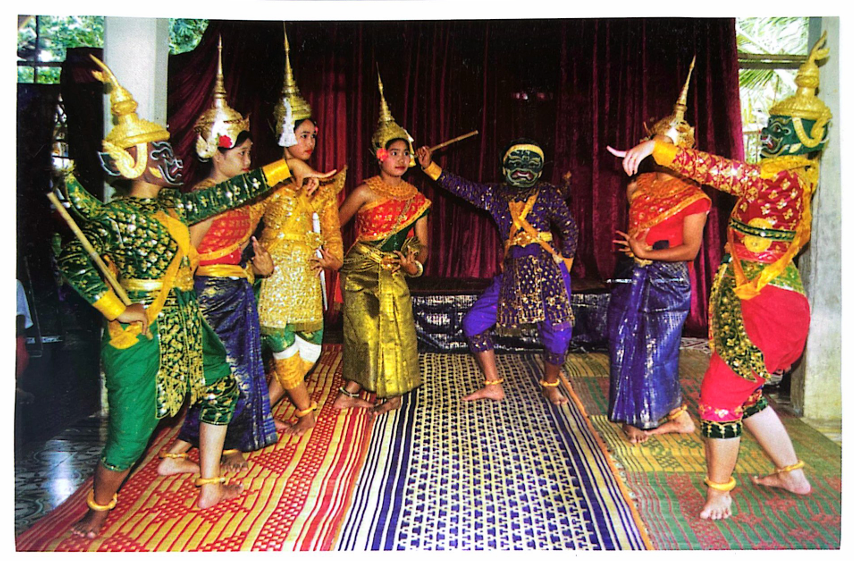

It is the author and researcher Chen Neak who proposed to evolve the name of this art form, villagers often refer to as “female theater”, to ពោល porl “spoken” female theater, a performance in which the dancers actually “say” something, “speak”. The 18th-century German singspiel comes to mind, but what makes this art form unique is the origin of the tales (told stories), and the combination of rituals performed in Cambodian most elaborate dance forms (Sampeah Kru [paying homage to the teacher], meditation and blessing before the performance…) with strong, village-based roots. While comparing Lakhoan Porl Srei with Classical or Royal theater (ល្ខោនក្បាច់បុរាណ Lakhoan Kbach Boran), the author indicates that the two often look the same but they are two distinguishable art forms [for instance, the modern “Apsara dance” repertoire of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia is not to be found here].

When the author and his colleagues (Professor Pech Tum Kravel, Hang Soth, Sok Sam Oeun, Hul Phoeun Neary, Ang Kimhour) started their research in the late 1990s, they met with a dance and drama teacher, ជា មុត។ Chea Samuth (Muth), at Wat Kien Svay Krao វត្តគៀនស្វាយក្រៅ, in Kandal Province,15 km south of Phnom Penh Independence Monument. Herself had studied this particular dance form with “an outstanding art teacher, Ms. Chin, who had come to teach the women in 1878, from កោះឧញ្ញាទ័យ Koh Ountay [? could it be Koh Okhna Tey (Silk Island, Phnom Penh area)?]. With the help of the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, and the support of UNESCO, her Lakhoan Porl Srei school performed the program Chey Sen at the Chaktomuk Theater on July 2, 1999.

This rebirth of a specific dance form may have not happened without a chance discovery narrated in the book:

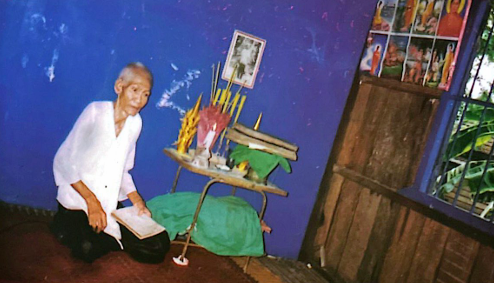

During the rainy season of August 1994, in search of the manuscript of the male mask theater for additional data on research missions, Chen Neak and Pech Tum Kravel stopped in front of a house in the northern part of Wat Kien Svay Krao [the pagoda, about 30 minutes drive south of Independence Monument, has markets and popular floating restaurants nearby] to buy food and water. At that time, they also asked for information about the manuscript from the seller and found out that this house was the house of Lok Yeay Kom, a widow and a manuscript keeper.The manuscript was placed sacredly on a pedestal tray on a small table, with a can of incense sticks in front of the photo of Lok Ta Chea Dek who was Lok Yeay Kom’s husband.

This is the only manuscript in Phum Thom commune, Wat Kien Svay Krao, Kien Svay district, Kandal province. The request for access from both of them was rejected because, since Lok Ta Chea Dek’s death, no one dared to open and read it. After all, it would lead to blindness. Of course, old people in the past tended to make such prophecies to keep young children from being exposed to specific things. During the Khmer Rouge era, books, and documents which were repositories of knowledge and the foundation for cultivating intellectuals were destroyed and considered enemies of this régime. Lok Ta Chea Dek, the manuscript keeper, tried to hide it by wrapping it in a piece of cloth and burying it in the ground near a bamboo grove. Every six months, Lok ta would secretly dig the bamboo grove to check the condition of the manuscript. This shows the devotion, and the courage to sacrifice one’s life to preserve the manuscript. He passed away in 1979, and this work was continued by his wife, Lok Yeay Kom, who was in front of the two researchers. After hearing such a heroic story, the parable of blindness was revealed. The two men then looked at each other with a conversation inside and agreed to reveal their true identity as conservators of Khmer art to Lok Yeay Kom in exchange for trust. She finally agreed to let the two men bring the manuscript for a close review.

Opening the manuscript was like the opening of a treasure trove of precious heritage that has brought excitement to these two art researchers. The manuscript is not only a valuable treasure in Kandal province along the Mekong River, but it is also valuable in the arts and culture. The manuscript almost 200 years old in age consists of stories, words dialogue for all the characters, poetic songs, and directing strategies. In addition, there are seven stories in the manuscript: Chey Sen ជ័យសែន, Chey Toit ជ័យទត្ត, Preah Chin Vongsa ព្រះជិនវង្ស, Preah Khour Buth ព្រះឃោប៊ុត, Lin Thong លិនថោង, Preah Sothun Neang Keo Monorea ព្រះសុធន នាងកែវមនោរា , and Preah Chin Vong ព្រះភិណវង្ស, all of which are literature from the Longvek period, which tends to be Brahminical instead of Buddhist. The manuscript here is not only a document written by hand, but also the key to the essential guideline of this Khmer art form.

If this document is not precisely dated in the book, “almost 200 years old” would situate it at the end of the 18th century, around 1790. Yet other sources claim it originated from the time of King Jayajettha II [Chey Chetta II] (r. 1619 – 1627), who established the royal capital in Udong. This is not surprising, as several royal documents from the Udong period have been kept in pagodas of the Kandal province. For instance, the Royal chronicle labeled Tuk Vil, was collated by the Venerable Has Suk in 1941 from a manuscript kept at the Tuk Vil Pagoda since at least 1901 [see Mak Phoeun, Histoire du Cambodge…].

In Cambodia, art traditions are often the only link to the country’s past. Khmerologist Madeleine Giteau has observed that “not a single ancient building or statue have been found” at Lovea Em, ancient capital city of the Kings of Cambodia, but “a tradition of royal dances has subsisted there. (Madeleine Giteau, Iconographie du Cambodge post-angkorien, PEFEO, 1975, p. 62)

In total, the author considers here 16 aspects of the dance form:

- និយមន័យ Definition

- លក្ខណៈពិសេសរបស់ល្ខោនពោលស្រី Features of Puol Srey Theater

- លក្ខណៈពិសេសក្នុងការបង្ហាញតួអង្គ Character presentation features

- ប្រភពល្ខោនពោលស្រី Source: Poul Srey Theater

- ប្រវត្តិល្ខោនពោលស្រី History of Puol Srey Theater

- រណ្តាប់ល្ខោនពោលស្រី រាំ ថ្វាយព្រះ Female singers dancing dancing to God

- រណ្តាប់សំពះគ្រូ (ក្បួនសំពះល្ខោនពោលស្រី) Salute to the teacher (salute to the female puppet theater)

- ពិធីសំពះគ្រូ ឬថ្វាយខ្លួន Teacher Salute Ceremony

- ឆាកសម្តែងល្ខោនពោលស្រី Puol Srey Theater

- ការតុបតែងលម្អឆាក Stage decoration

- ការបំភ្លឺភ្លើង Lighting

- ពិធីហោមរោងមុនការសំដែង Pre-performance, hall performance

- វិធីសាស្ត្រ និងមធ្យោបាយសំដែង (សមាធិ) Methods and means of performance (meditation)

- ឧទាហរណ៍រឿងជ័យសែន (ទម្រង់ល្ខោនពោលស្រី) Example of Chey Sen (Puol Srey)

- បញ្ហាសមាធិ របស់ក្រុមល្ខោនពោលស្រី Meditation issues of Puol Srey Theater Group

- របៀបសំដែង How to perform

- ការសម្តែងកាយវិការ Gestures

- ការសំដែងពាក្យសំដី Verbal performance

- ការតុបតែងកាយតួអង្គ (សម្លៀកបំពាក់តុបតែងក្បាល) Character makeup (headdress)

- វង់តន្ត្រីប្រគំជាមួយការសម្តែងល្ខោន Orchestra performing with theater performances

- អំពីទំនុកច្រៀង និង របៀបរៀបចំចុងចួន ចងក្រងពាក្យពេជន៍ About the lyrics and how to prepare them.

Note:

To this day, with the support of the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, Ms. Pum Sok Khim devotes a small space of her house located in Kien Svay Kroa to the daily practice of the dancers.

Tags: Khmer arts, dance forms, Cambodian dance, manuscripts, 1990s, King Chey Chetta II

About the Author

Neak Chen

Chen Neak ចិន្ទ នាគ (29 Dec. 1946, Kompong Cham Province — 2 Sep. 2011, unknown) was a speak-theater professor, a writer and a member of the Research Committee on Culture and Arts at the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts (MCFA).

Chen Neak was born into a poor peasant family in Kampong Cham province, firts studying at the local pagoda, then moving to Wat Saravan at 18 in order to study at the National Theater School. In 1967, he majored and joined the National Theater.

In his career as an artist, art director, and professor, Chen Neak also traveled to Laos, Vietnam, the Soviet Union, the Philippines, China, and Thailand to attend exchange programs and to share Cambodian art knowledge on the international stage. As an assistant and colleague of Pech Tum Kravel, he researched the history of Khmer theater and dance, under the direction of Chheng Phon, head of the MCFA Research Committee on Culture and Arts, contributing to the rebuilding of Khmer cultural traditions after the Khmer Rouge years.

Chen Chanratana ចិន្ត ច័ន្ទរតនា, the founder of the Khmer Heritage Foundation កេរដំណែលខ្មែរ [Kerdomnel Khmer], is Chen Neak’s son.