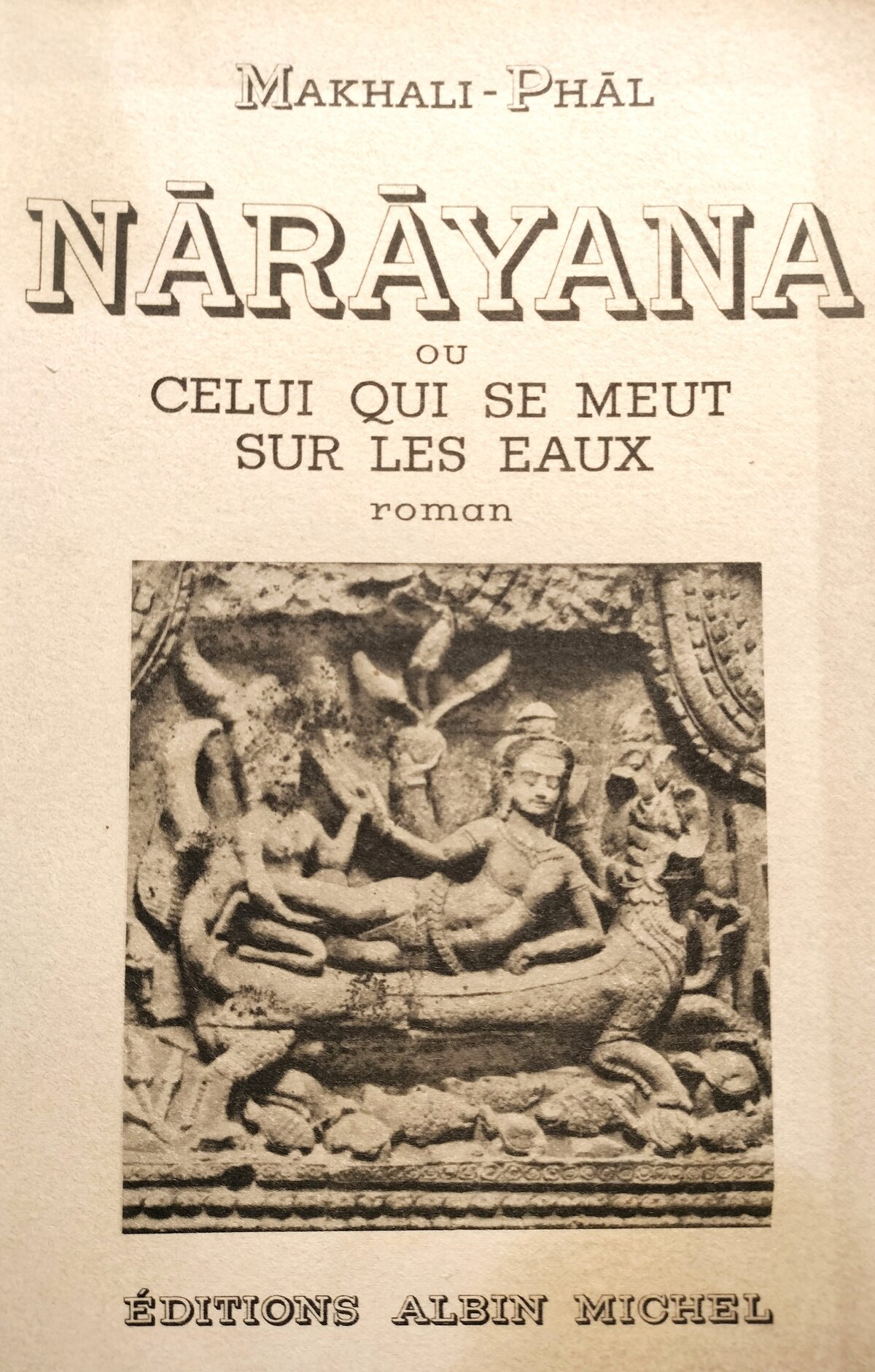

Nārāyana ou Celui qui se meut sur les eaux

by Makhali-Phal

Cambodia as the ultimate land of the Creation, where all living beings converge to the revelation of the Supreme Being.

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, paperback

- Publisher

- Albin Michel, Paris

- Published

- 1942

- Author

- Makhali-Phal

- Pages

- 1

- Language

- French

In this lyrical, symbolist novel, Nārāyaṇa (Sk. नारायण) is more than one of the forms and names of Vishnu, the representation of the masculine principle, or the Supreme Being in Vaishnavist tradition; he is a Khmer prince destined to become a modern bodhisattva, an aspiring Buddha who studied in France and encountered Christian monotheism, ‘He Who Moves Over The Waters’ 2.0 version, if this liberty with terminology history is allowed.

And in the author’s inspired cosmogony, Cambodia is more than a ‘chosen land’, to use a Biblical term: it’s a land that seems to have been designed to keep reminding us of the secret ways of the Creation. This is its calling, its ‘vocation’, to quote the author. And when the novel ends, the primordial tiger and tigress dies, and transubstantiate into humanity:

“Chaque terre a sa vocation. Celle du Cambodge, voué six mois au feu et six mois au déluge, consiste à né pouvoir s’éloigner de la première semaine de la création. Cette terre a l’air de dire: je suis le regret vivant du Premier Jour. Je né me console pas de la mort de ce Jour où Dieu s’est écrié : Que la lumière soit! Inconsolable malgré la survivance des trois grandes périodes qui composent sa structure : l´âge préhistorique, l’âge angkoreen et l’âge bouddhique qui subsistent, côte à côte, dans la jungle, sur les ossements des iguanodons et des lézards du tonnerre. Mais la terre cambodgienne né se préoccupe que d’une chose ; revenir au premier jour de la création. Peu lui importent les villes théologales qui germèrent sur toute sa surface et ces hommes des tribus primitives qui vivent encore dans la jungle, comme les pasteurs de mammouths, sous les vestiges de la plus hautaine des civilisations, celle des rois d’Angkor. [“Each land has its vocation. That of Cambodia, destined six months to the fire and six months to the deluge, resides in not being able to move away from the first week of creation. This land seems to say: I am the living longing for Day One! I am not consoled for the death of this Day when God cried out: Let there be light! Inconsolable despite the survival of the three great periods that make up its structure: the prehistoric age, the Angkorean age and the Buddhist age that subsist, side by side, in the jungle, on the bones of iguanodons and thunder lizards. But the Cambodian land only cares about one thing: to return to the first day of creation. It doesn’t really care the theological towns that sprung up over its entire surface and those primitive tribesmen who still live in the jungle, like shepherds of mammoths, under the vestiges of the haughtiest of civilizations, that of the kings of Angkor.

¨Quand après avoir été, six mois, lumière de la mort, le Cambodge épouse son fleuve et devient, à l’intérieur de I´Indo-Chine, la mer, le souvenir du Grand Déluge où Dieu avait autrefois noyé toute la terre, étreint l´âme de ses jungles inondées et l´âme de ses bêtes réfugiées sur les montagnes. Le souvenir du Grand Déluge lève obscurément, dans l’âme de toute créature, le souvenir d’autres déluges qui noyèrent les créations antérieures à la naissance de la terre, et par le retentissement illimité de ces déluges qui engendrèrent pour ainsi dire le Déluge de Noë, il ressuscite, dans l´âme de toute créature, l’énormité de ces créations antérieures que Dieu a passées sous silence, de l’avis meme de saint Augustin, qui n’a pas jugé bon de révéler à l´intelligence d’un Moïse ou d’un Manou, sans doute à cause de l’épouvante attachée à la quatrième dimension de ces créations antérieures. Seul, dans les jungles du Cambodge qui se métamorphose en mer, le déluge ressuscite l’image de ce que Dieu a volontairement passé sous silence. Mais quand sur la mer, on né voit plus la moindre branche, pas la plus petite feuille, que tous les arbres sont bien retournés et bien tassés dans le ventre de l’eau, comme des enfants tapis dans la matrice, alors le souvenir de tant de déluges disparaît à la suite des arbres comme par enchantement. Du haut des monts, les bêtes de la jungle se penchent sur la mer aussi lisse qu’un visage d’enfant et cessent de trembler. Il semble que la nature entière communie dans le pressentiment tranquüle et solennel que tout soudain va revenir comme au premier jour de la création. [¨When after having been for six months the light of death, Cambodia marries its river and becomes, inside Indo-China, the sea, the memory of the Great Flood where God had once drowned the whole earth, embraces the soul of its flooded jungles and the soul of its beasts sheltering in the mountains. The memory of the Great Deluge obscurely raises, in the soul of every creature, the memory of other deluges which drowned the creations prior to the birth of the earth, and by the unlimited repercussions of these deluges which engendered, so to speak, Noah’s Flood, he resurrects, in the soul of every creature, the enormity of those previous creations on which God has decided to keep quiet, even in the opinion of Saint Augustine, who did not see fit to reveal to the intelligence of a Moses or a Manu, no doubt because of the terror attached to the fourth dimension of these earlier creations. Alone, in the jungles of Cambodia which are transformed into the sea, the flood brings to life the image of what God has deliberately omitted to mention. But when on the sea, you no longer see the slightest branch, not the smallest leaf, when all the trees are well turned over and firmly packed in the belly of the water, like children crouching in the womb, then the memory of so many deluges disappears following the trees as if by magic. From the top of the mountains, the beasts of the jungle lean over the sea as smooth as a child’s face and stop trembling. It seems that all of nature is united in the quiet and solemn presentiment that all of a sudden will return as on the first day of creation.”]

“Alors regardez! C’est au tour d’un autre souvenir de s’emparer de la mer. Le souvenir de l’immortel glisse sur le calme des flots au-devant du mortel. Et quand il se met à marcher sur la pointe des vagues doucement et majestueusement, qu’est-ce qui crie à l’élement mortel: disparais, toi aussi ? L’élément mortel n’a‑t-il pas envie de rejoindre au fond de l’eau, au fond de lui-même, le souvenir diluvien englouti avec les arbres? Mais non, il s’élance sans crainte vers le souvenir de l’immortel comme un enfant bondit vers son père. Et le souvenir de l’immortel étale la mer comme une prière sur le Cambodge.” [“Now, behold! Now comes over another memory to take hold of the sea. The memory of the Immortal glides upon the quiet waters ahead of the mortal. And when he begins to walk on the tip of the waves, gently and majestically, what is it that cries out to the mortal element; disappear, you too ! Doesn’t the mortal element want to reach the bottom of the water, the bottom of itself, the bottom of the memory of the Flood engulfed with the trees? But no, it rushes without fear towards the memory of the immortal like a child leaps towards its father. And the memory of the immortal spreads the sea like a prayer over Cambodia.”] (p 10 – 11).

Tags: Cambodian literature, French literature, symbolism, myths of creation, Mahayana, Buddhism, monsoon, monsoon climate, climate

About the Author

Makhali-Phal

French-Khmer poetess and novelist Makhali-Phal (Nelly-Pierrette Guesde (21 Sep. 1898, Phnom Penh — 15 Nov. 1965, Pau, France) was brought to France in 1906 with the Cambodian Royal Court during the official visit to Exposition Universelle de Marseille, yet wrote almost exclusively about the history, mythology and landscapes of her native country, Cambodia. Her mother was a Cambodian lady, her father, Pierre Guesde, was the Secretary of French Residence-superieure in Phnom Penh in the 1890s.

We do not know for sure what happened to young Pierrette before she arrived in Paris around 1930. Some sources state that she grew up in a Catholic convent at her father’s wishes, other that Pierre Guesde entrusted the child to his parents who lived in Pau (Southwestern France). What seems clear is that Guesde, even if he acknowledged paternity of his Cambodian daughter, was otherwise quite busy with his “legitimate” marriage and his business career.

In 1933, she published her first poem, Cambodge, and four years later her Chant de Paix (Royal Library of Phnom Penh and Buddhist Institute), ‘dedicated to the Khmer people’, that has been translated into English (Song of Peace, 2010, DatASIA) and Khmer languages. Her novels such as Le Roi d’Angkor (1952) or Le feu et l’amour (1953) reflect a vast knowledge of the Angkorean civilization, and a sensuality, musicality and mysticism reminiscent of the French symbolist literary movement, with noticeable influences from her Buddhist background — even if her father, Mathieu Pierre Théodore Guesde (a colonial administrator born in Guadeloupe and married to a young Cambodian attached to the Royal Palace, Neang Mali) made her enter a Catholic convent at a young age.

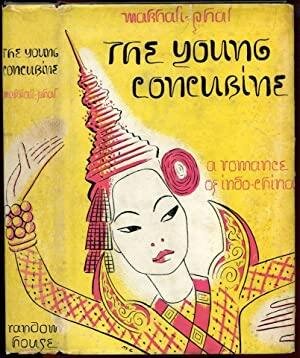

In 1942, the publication by Random House of her novel The Young Concubine made Makhali-Phal a literary celebrity in the USA. The editor noted: ‘Her pen-name, reputedly given to her by King Sisowath, refers to the sound made by the blade of the plow of the goddess Kali. Born in Phnom Penh, Makhali-Phal’s work concerned the perils of metissage (mixed-race identity) n a colonial context. In this novel, for example, a Khmer Princess educated in Paris struggles with her place at the intersection of East and West.’

The poetess who invoked ‘Ô Europe, ô Asie, tristes sœurs jumelles’ (‘Oh, Europe, Oh, Asia, sorrowful twin sisters’) launched ethereal bridges between East and West, although she noted about her work: “Je transposais dans la langue de ma mère le rythme des gongs, les répétitions, les images cruelles, voluptueuses et théologales qui ressuscitaient mes ancêtres d’Angkor et qui m’en délivraient” (“I transposed into my mother’s native language the rhythm of gongs, the repeating echoes, the fierce, voluptuous and mystical images which resuscitated my Angkorean ancestors and yet set me free from them.”)