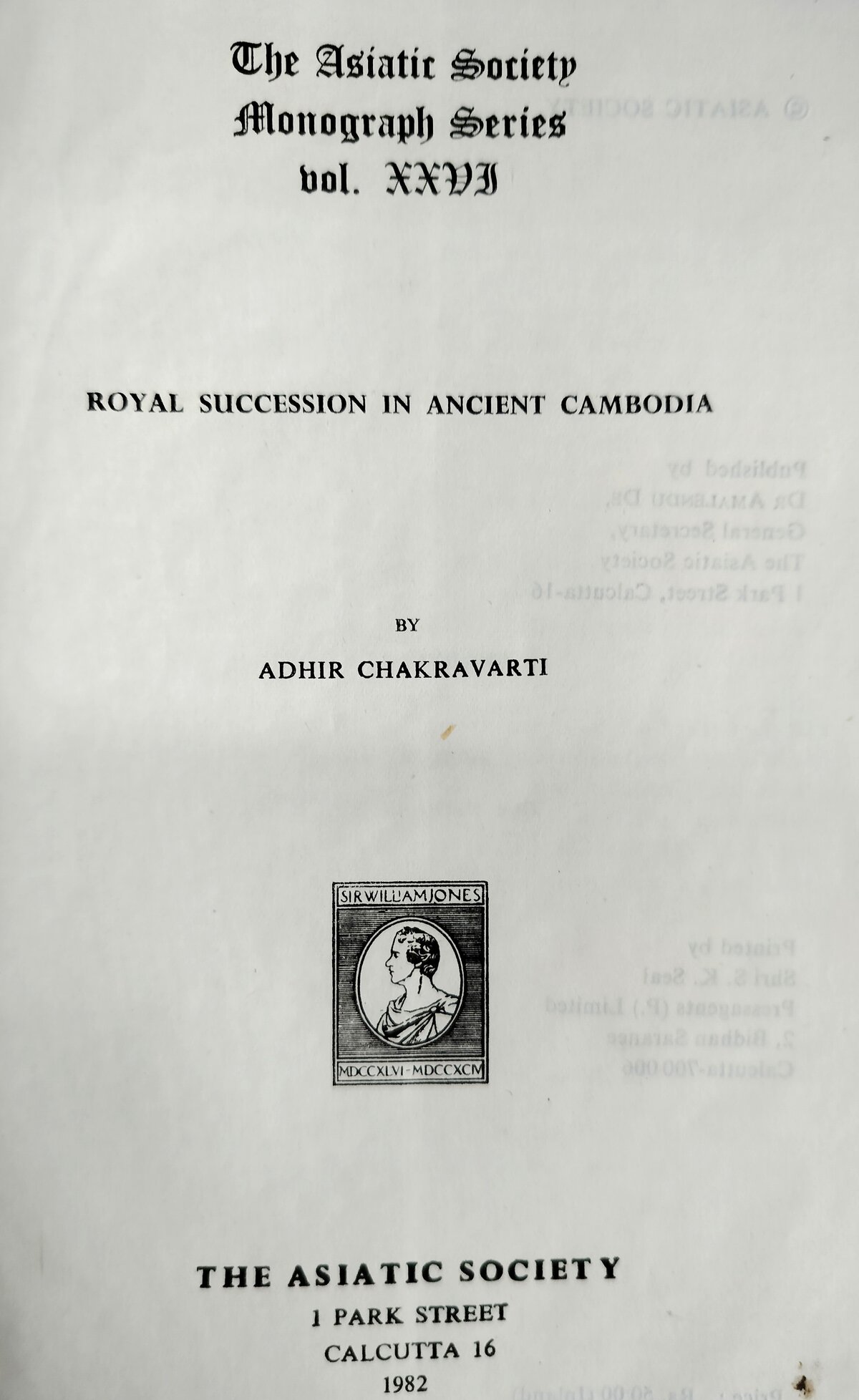

Royal Succession in Ancient Cambodia

by Adhir Chakravarti

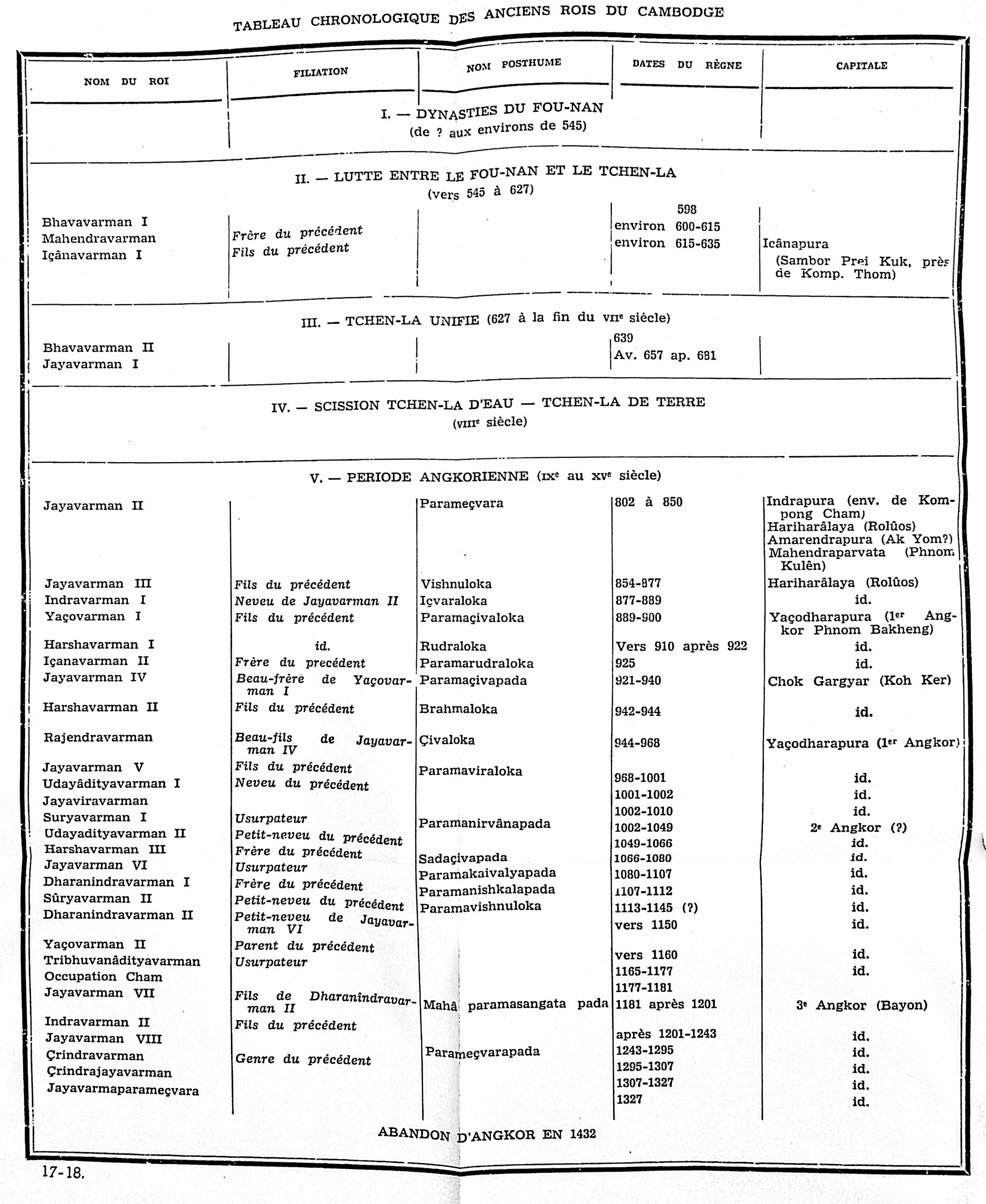

Matrilinear and patrilinear succession lines, plus some conquerors or usurpers: the complex genealogy of pre-Angkorean and Angkorean sovereigns.

- Formats

- ADB Physical Library, hardback

- Publisher

- The Asiatic Society Monograph Series vol. XXVI, Calcutta.

- Edition

- HE Julio Jeldres donation, August 2023

- Published

- 1982

- Author

- Adhir Chakravarti

- Pages

- 119

- Language

- English

The author, who had previously given the most complete commented publication of the Sdok Kak Thom inscription [1], shares with us a novel and well-balanced view on how royal succession happened in pre-Angkorean and Angkorean, structured arount this core thesis: “Repercussions of the contact and conflict between the indigenous [‘Khmer’] matrilinear system and the intruding patrilinear system of India made themselves felt all through the centuries of living Indian presence in Cambodia.” (p 5)

After dismissing both Eveline Porée-Maspero’s hypothesis of some ‘lunar’ (matrilinear) and ‘solar’ (patrilinear) dynasties in Ancient Cambodia, and George Coedès’s assumption that the female line prevailed only when there was no lawful male inheritor to the throne, or when some adventurer seized the throne, the author goes on with a detailed study of inscriptions and of Chinese sources to show the ambivalence of the Khmer elites regarding the matrilinear and patrilinear principles. From that minitious epigraphic exploration, the author proposes the following balance (pp 101 – 4):

- Patrilinear Succession, A) Definite cases: 1) Funanese Period: 4, 2) Tchen-la Period: 2, 3) Divided Tchen-la Period: 2, 4) Ankorian Period: 12, B) Probable cases: 4. Total: 24.

- Matrilinear Succession, A) Definite cases: 1) Funanese Period: 10, 2) Ankorian Period: 12. Probable cases: 2. Total: 24.

- Accession to the throne by conquest: 1) Mythical Period: 2, 2)Funanese Period: 2, 3) Tchen-la: 3, 4) Divided Tchen-la: 2, 5) Ankorian Period: 13. Total: 21.

- Election of kings: 1) Funanese Period: 2. Total: 2.

- Unknow relationship with predecessors: Total: 10, including immediate successors of Kaundinya-Hiun-Tien, Yasovarman II, Bhavavarman II, Harshavarman IV, Nippanbat-Mohanippanbat.

There is also the fascinating case of Princess Sri Vijayendralaskmi, mentioned in the Phnom Sandak inscription as Jayavarman VI’s spouse, but who had been before him the spouse of this king’s yuvaraja (heir? brother? father?), and at Jayavarman VI’s death the wife of his elder brother Dharanindravarman I: “this princess who was successively given to three brothers beginning with the youngest and ending with the eldest has herself been described as the fruit of Fortune and Victory.” (p 83)

The conclusion resonates much farther than matters of royal succession: “The failure of the typical Indian principle of patrilinear succession over that of its opposite viz. matrilinear succession in the matter of royalty, which was acknowledgedly an institution of Indian importation in Cambodia, is indicative of the fact that the extent of Indian cultural in Cambodia was not so profound as Indianists would like us to believe.”

Compare Adhir Chakravarti’s elaborate genealogical research with this Chronological Chart from the popular ‘Les Monuments d’Angkor’ Guide by Maurice Glaize (1948). For instance, the latter summarily labels Suryavarman I as ‘usurpateur’ (usurper), while the former reminds us that this king ‘descenced from Indravarman I in the maternal line, and his chief queen Viralaksmi from Harshavarman I and Isanavarman II in the maternal line.

[1] Sdok Kak [or Kok] Thom (Thai สด๊กก๊อกธม, Sadok Kok Thom, Khmer: ស្តុកកក់ធំ, Sdŏk Kák Thum [meaning unknown, ‘great temple with reed lake’?]), an 11th-century Khmer temple initially dedicated to Shiva near the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet and only 35 km northwest to the Cambodian town of Sisophon, is held as the largest Khmer temple in eastern Thailand. Philip N. Jenner, reviewing Adhir Chakravarti’s work in Asian Studies (2011), noted that “Sdok Kak Thom is the modern Khmer name of the ancient sanctuary of Bhadraniketana. The inscription of this name, K.235, was engraved on the four sides of a sandstone stele discovered in the sanctuary compound sometime before 1884, and consists of 194 lines in Sanskrit and 146 lines in Khmer. Assigned to A. D. 1052, it is the most important single text in the entire corpus of Cambodian epigraphy, as much for its length as for its content. The Sanskrit and Khmer portions together constitute our best source of information on the genesis of the Angkorian state. The Khmer portion is our most extensive specimen of Old Khmer prose. Dating from a period when Angkorian culture was at a peak of development, it reflects an ease of literary expression that sets the standard against which the earlier and later language must be measured. The inscription is therefore a primary source for the early history of Southeast Asia and a document of major linguistic value. The stele on which it was cut was destroyed in 1958 by a fire, which swept the National Museum in Bangkok where it had been kept. Fortunately, three sets of estampages that had been made from it are preserved in Paris. The inscription was first brought to public notice by Aymonier, who published parts of it in 1901. In 1915 Finot attempted a full transliteration and translacion; this justified a new edition by Coedès and Dupont in 1946. In 1953, R. C. Majumdar published a compressed translation of the Khmer portion, without the text , together with a devanagarf transcription of the Sanskrit portion evidently based on Finot’s version. Professor Chakravarti’s work is thus the fifth in line, while Part II alone is also the fullest. The author’s purpose in Part I is to analyze and interpret the inscription, to define its place in history, and to use its data to enlarge our understanding of the interaction between Indian and Khmer culture. The ten chapters into which the volume is divided include two on political forms, four on social organization, one on economy, and two on the cult of the devaraja.”

Tags: Khmer Kings & Queens, chronology, royal succession, Indian studies, Sdok Kok Thom, King Jayavarman VII, gender roles, women, genealogy, epigraphy, Indian influences

About the Author

Adhir Chakravarti

Prof. Adhir Chakravarti (24 Apr 1932, Kotalipara (now in Bangladesh — 20 Dec 1993, New Delhi, India) was a Sanskritist and Indian historian who studied extensively Southeast Asian cultures and Indian influences there.

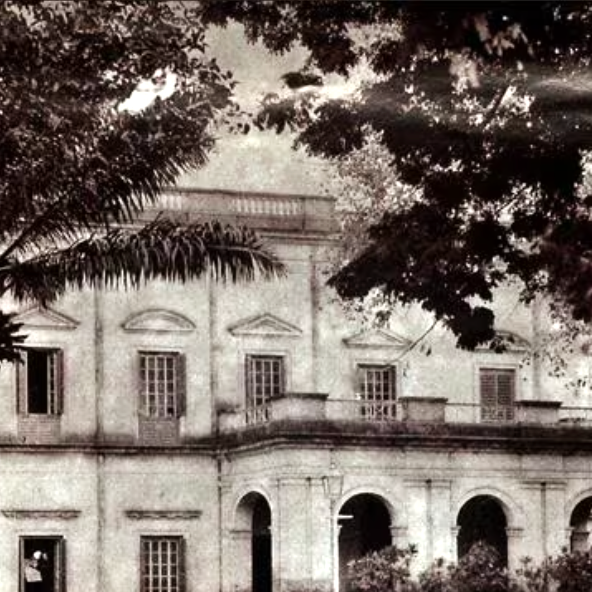

After studying under Dr. Niharranjan Ray’s supervision, he worked with the Calcutta (Kolkata)-based Asiatic Society [1] in the 1970s and 1980s. Niharranjan Ray (1903−1981), who had been General Secretary of the Asiatic Society from 1949 to 1950, became in 1965 the First Director of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla.

After researching Khmer and Sanskrit inscriptions at Sorbonne University, Paris, under Prof. George Coedès, he became professor and principal of the Jarghram Raj College in 1973, and served as Director of Archives of West Bengal for many years.

In April-May 1985, he toured Indonesia, Cambodia and Thailand for a field study exploration that led him to write the paper ‘The Economic Foundations of Three Ancient Civilizations of South-east Asia: Borobodur, Dvaravati and Angkor’.

Amongst Prof. Chakravarti’s publications, the most referred to in the field of Khmer studies is certainly his publication and commentaries on The Sdok Kak Thom Inscription : Part I: A Study in Indo-Khmer Civilization, with a preface by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. Calcutta: Sanskrit College (Calcutta Sanskrit College Research Series, No. 111), 1978. xii, 367 p. Part II: Text, Translations, and Commentary, with a preface by Dinesh Chandra Sircar. Calcutta: Sanskrit College (Calcutta Sanskrit College Research Series, No. 112), 1980. 272 pp. It is said that his critique of R.C. Majumdar’s contribution to he history of Southeast Asia’s ‘Indianization’ changed the way Indian scholars considered ancient local cultures and polities.

In 2007, Dr. Haraprasad Ray, one of the very few Indian scholars dealing with India-China relations, edited a collection of twenty essays by the late Adhir Chakravarti, covering such topics as Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Kamboja, Java-Sumatra, Dvaravati, Annam, Champa, Nanchao (Mithila Rastra), Bali, Heling-Kalinga, Harikela’s (South-East Bengal’s) foreign contacts, ancient Bengal and Orissa’s relations with China, a re-examination of the issue of Indian Cultural expansion in South-East Asia and dimensions of India-China trade and relations at a time when Chinese Navy was in its early stage of development: Studies on India, China and South East Asia: Posthumous Papers of Prof. Adhir Chakravarti, ed. Haraprasad Ray, R.N. Bhattacharya Publisher, 512 p., 2007. ISBN: 8187661399.

[1] Founded by Sir William Jones in Calcutta in 1784, the Asiatic Society published the first issue of The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in March 1832, and its library holds manuscripts dating back to 1732. See Supriya Guha’s piece in Hindustan Times, 29 Oct. 2016.

The original Asiatic Society building in Park Street, Kolkata, built during 1805 – 1808. (India International Centre via Hindustan Times).