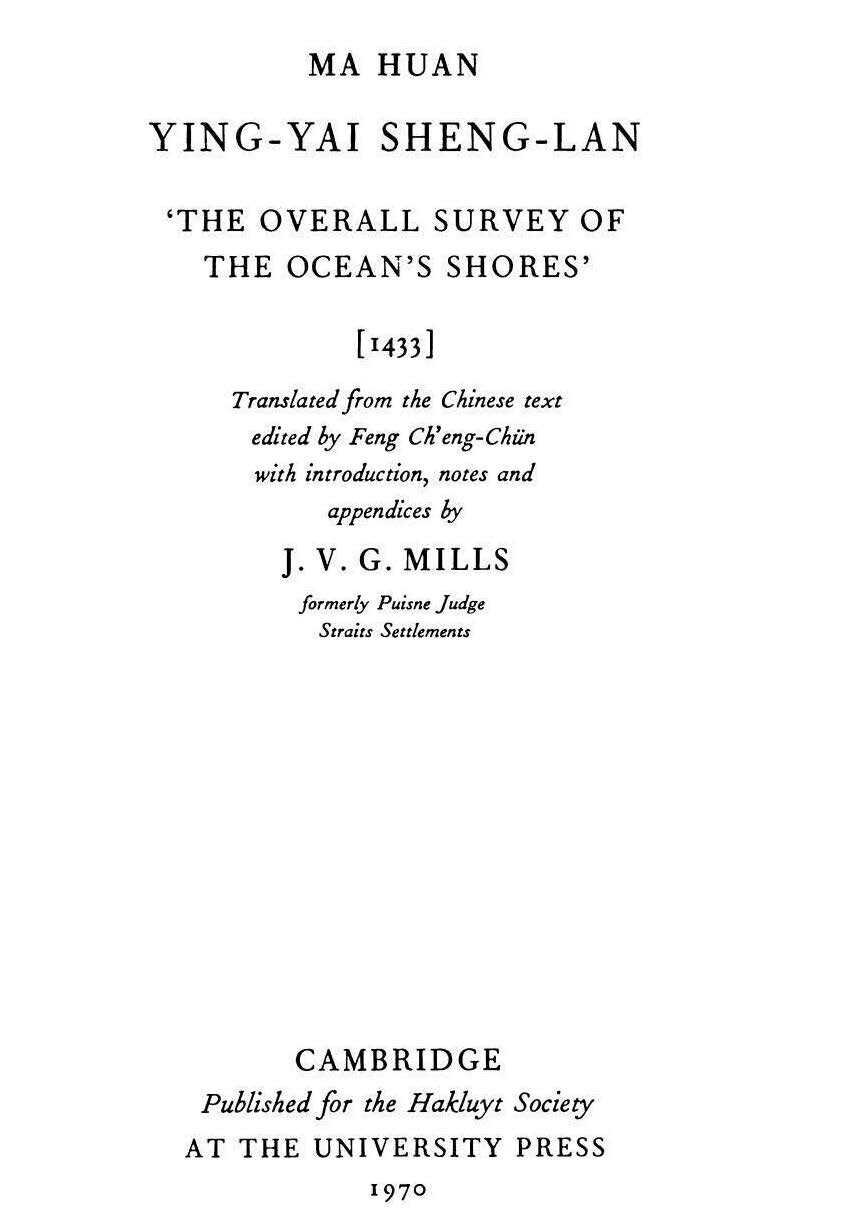

Ying-yai Sheng-lan 瀛涯勝覽 | 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores'

by Ma Huan & John Vivian Gottlieb Mills

The reference travelogue of Ma Huan, interperter and translator with Zheng He's flotilla: how China saw the world in the early Ming dynasty era.

- Format

- e-book

- Publisher

- Cambridge University Press for the Hakluyt Society, Cambridge, UK | (reprinted 1997 by White Lotus, Bangkok)

- Edition

- Haklyut Society Digital Publications, no 42.

- Published

- 1970

- Pages

- 413

- Language

- English

pdf 34.6 MB

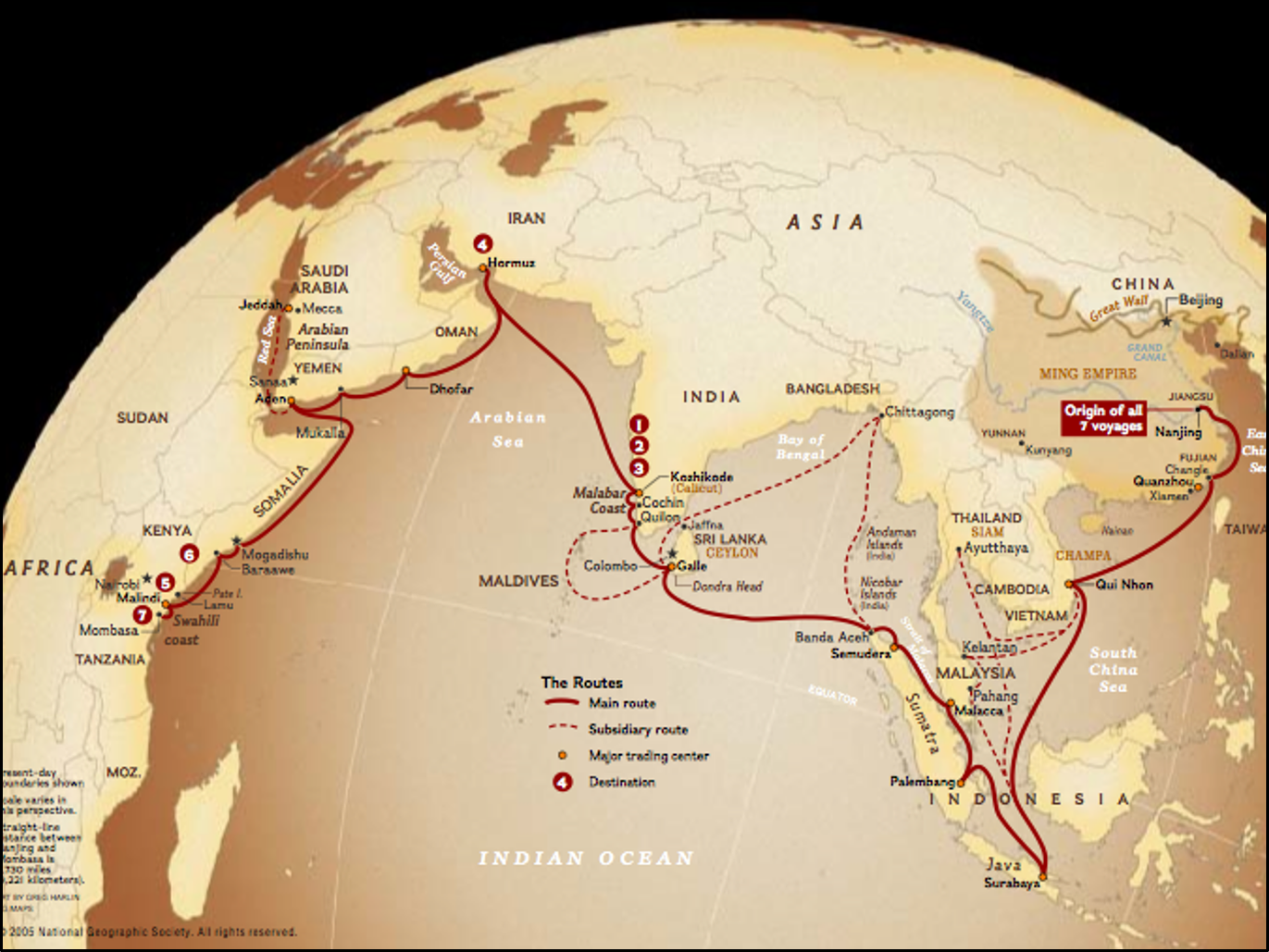

Starting from its title, this vast description of the ocean and surrounding lands from the shores of China to Malabar, the Maldives, Hormuz and the “heavenly square”(Mecca) written by Ma Huan in the mid 15th century is a translator’s puzzle: while several scholars had opted for ‘Triumph.ant Visions of the Boundless Ocean’ — and even ‘The Beautiful Views at the Boundary of the Immortals’ Ying Island’ –, the present translation title is definitely more sober.

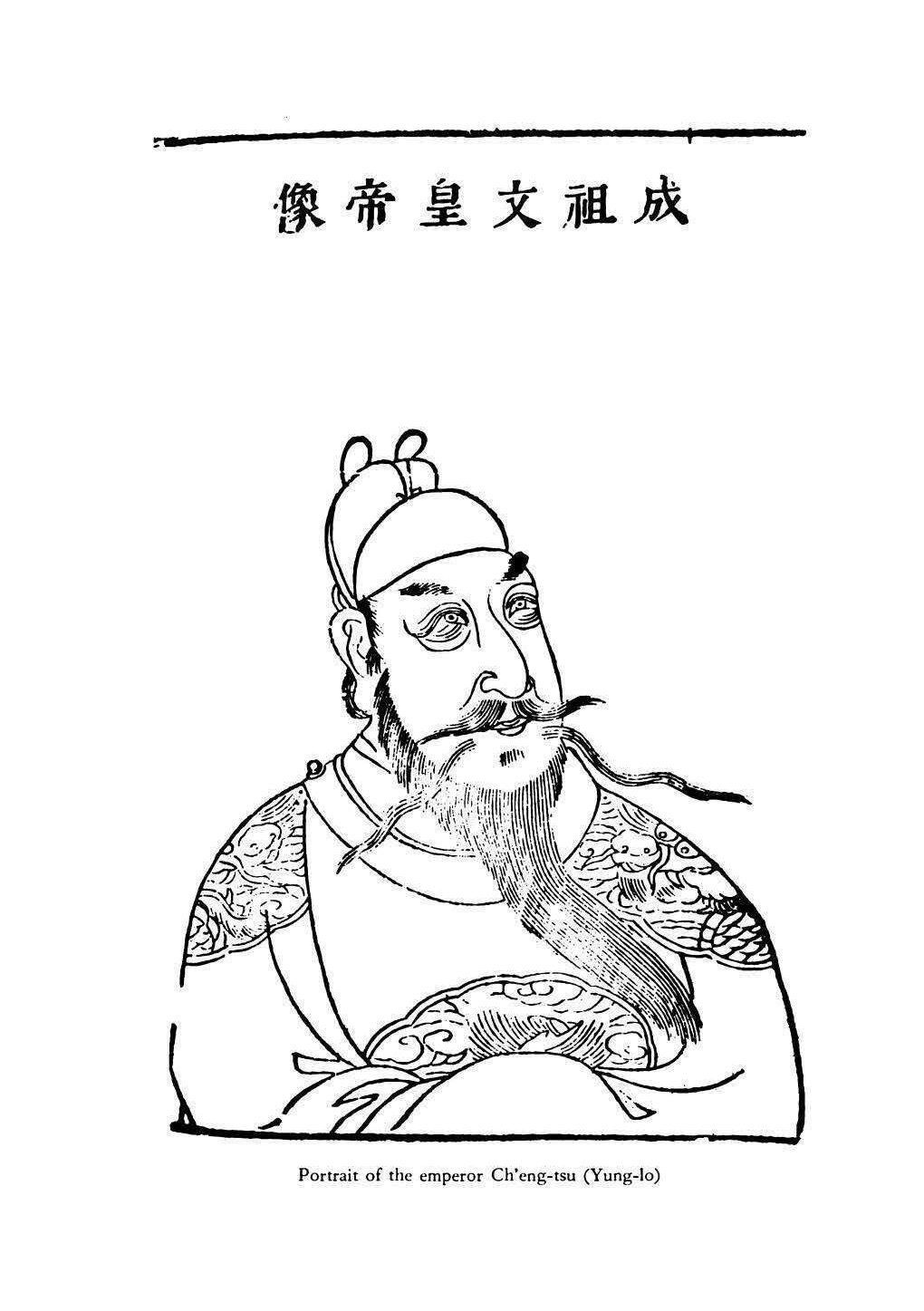

Based on the modern Chinese edition of reference by Feng Ch’eng-chun [Feng Chengjun] (Shanghai, 1935; republished Peking, 1955), J.V.G. Mills’ monumental work opens with a presentation of the author himself, Ma Huan, and with the historic backdrop of “Cheng Ho [Zheng He] and his expeditions” to the “Western Ocean”. Cheng Ho, the ‘grand eunuch’ (t’ai chen), was the first of his kind to be appointed to a major military rank by Emperor Yung-lo (often romanized Yongle).

Contrary to Zhu Daguan’s visit to Chenla (Cambodia) one-and-a-half century earlier, the area was not the main destination of these expeditions. They were heading to “the West”, both for strategic-military — perfect the knowledge of the Indian, Arabian and African coasts — and religious — both Zheng He and Ma Huan were of Muslim creed, and the pilgrimage to Mecca was high on their list, Zheng He’s grandfather having been himself a “hadjji”.

Nevertheless, the first port-of-call of all of seven expeditions outside the Chinese realm was ‘Hsin Chou Chiang’, the “New Department Haven”(Qui Nhon in modern Vietnam), very close to Vijaya, the former Champa Kingdom capital, linked to Chan ch’eng [Champapura, City of the Chams]. where the fleet stayed two weeks. Among the observations made in Champa:

- “This is the country called Wang she ch’eng in the Buddhist records. It lies

[in the] south of the great sea [which is] south of the sea of Kuang tung. Starting from Wu hu strait in Ch’ang lo district of Fu chou prefecture in Fu chien [province] and travelling south-west, the ship can reach [this place) in ten days with a fair wind.7 On the south the country adjoins Chen la; on the west it connects with the boundary of Chiao chih;[and] on both east and north it comes down to the great sea.” [Chenla was a country only know by hearsay to the author]. - The King’s attire: “Going south-west for one hundred li you come to the city where the king

resides; its foreign name is Chan city. The city has a city-wall of stone, with openings at four gates, which men are ordered to guard. The king of the country is a So-li man, [and] a firm believer in the Buddhist religion. On his head he wears a three-tiered elegantly-decorated crown of gold filigrees resembling that worn by the assistants of the ching actors [The assistants of the ching actors played ‘painted face roles portraying bad characters with vigorous action’ (A. C. Scott, The Classical Theatre of China (London, 1957), p. 229; Pelliot, ’ Encore’, p. 217] in the Central Country. On his body he wears a long robe of foreign cloth with small designs [worked in] threads of the five colours [White, black, red, azure, and yellow], and round the lower part [of his body] a kerchief of coloured silk; [and] he has bare feet. When he goes about, he mounts an elephant, or else he travels riding in a small carriage with two yellow oxen pulling in front. The hat worn by the chiefs is made of chiao-chang leaves, and resembles that worn by the king, but has gold and coloured ornamentation; [and] differences in [the hats denote] the gradations of rank. The coloured robes which they wear are not more than knee-length, and round the lower part [of the body they wear] a multi-coloured kerchief of foreign cloth.As to the colour of their clothing: white clothes are forbidden, and only the king can wear them; for the populace, black, yellow, and purple coloured [clothes] are all allowed to be worn; [but] to wear white clothing is a capital offence. ” - “As to the colour of their clothing: white clothes are forbidden, and only the king can wear them; for the populace, black, yellow, and purple coloured [clothes] are all allowed to be worn; [but] to wear white clothing is a capital offence. The men of the country have unkempt heads; the women dress the hair in a chignon at the back of the head. Their bodies are quite black. On the upper part [of the body] they wear a short sleeveless shirt, and round the lower part a coloured silk kerchief. All [go] bare-footed.”

- “When men and women marry, the only requirement is that the man should first go to the woman’s house, and consummate the marriage. Ten days or half a moon later, the man’s father and mother, with their relatives and friends, to the accompaniment of drums and music escort husband and wife back to [the paternal] home; then they prepare wine and play music (…)

When men and women marry, they first of all invite a Buddhist priest to escort the groom to the woman’s family-house; and then they direct the Buddhist priest to take some of the maiden’s virginal blood and dab it on the man’s forehead; this (ceremony] is called li shih. After that the marriage is consummated. Three days later they again invite a Buddhist priest and the relatives and friends, and, bearing areca-nut and a decorated boat and other such things, they escort the husband and wife back to the man’s family house, where they prepare wine, play music, and entertain the relatives and friends.” [Mills’ footnote: “On this custom in Thailand and Cambodia see Duyvendak’s note (Duyvendak, Ma Huan, p. 40); Kung Chen states that the forehead of both groom and bride was dabbed, and considers the custom very laughable; the subject is discussed at length by H. Iwai, ‘The Buddhist Priest and the Ceremony of attaining Womanhood during the Yuan Dynasty’, Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunco, no. VII (1935), pp. 105 – 61. Li shi/1 (Giles, nos. 6885; 9905) means ‘profitable business’; Iwai has considered the origin and use of the expression in the present context; he concludes that the ceremony was called Ii shih because this phrase was applied to gifts made on the occasion of a wedding in South China (Iwai, pp. 137 – 42). For pre-marital formalities in modem times see Blanchard, pp. 4 34 – 5.”] - “When the king of the country has reigned for thirty years, he abdicates and becomes a priest, directing his brothers, sons, and nephews to administer the affairs of the country. The king goes into the depths of the mountains, and fasts and does penance, or else he [merely] eats a vegetarian diet. He lives alone for one year. He takes an oath by Heaven and says’ When formerly I was the king, if I transgressed while on the throne, I wish wolves or tigers to devour me, or sickness to destroy me.’ If, after the completion of one whole year, he is not dead, he ascends the throne once more and administers the affairs of the country again. The people of the country acclaim him, saying ‘Hsi-Ii Ma-ha-la-cha’ [Sri Maharaja, Sacred Monarch in Sanskrit], this is the most venerable and most holy designation.”

- “In their trading transactions they currently use pale gold which is seventy

per cent [pure], or else (they use] silver. They very much like the dishes, bowls, and other kinds of blue porcelain articles, the hemp-silk, silk-gauze, beads, and other such things from the Central Country, and so they bring their pale gold and give it in exchange. They constantly bring rhinoceros’ horns, elephants’ teeth, incense, and other such things, and present them as tribute to the Central Country.”

About Chenla and Khmer appellations in the text

“Different appellations are given for the same place, for instance, Chen la and Kan-po-chih for Cambodia; but where variants of the same name are involved, there are separate entries only if the first syllable is different; if the first syllable is the same, a variant form is added in brackets; thus, in the case of Cambodia, there are separate entries for Kan-po-chih and Chien-pu-chai, but after ‘Kan-po-chih’ is added ‘(Kan‑p’ o‑che) ‘.” As for ‘Khmer’, the Chinese transliteration used is Chi-mieh.

Admiral Zheng He statue at Quanzhou Maritime Museum, China

Zheng He, the man and the legend in Southeast Asia

Among the Chinese diaspora in Asia, Zheng He became a figure of folk veneration. Even some of his crew members who happened to stay in some port sometimes did so as well, such as “Poontaokong” on Sulu. The temples of the cult, called after either of his names, Cheng Hoon or Sam Po, are peculiar to overseas Chinese except for some communities in Indonesia, and a single temple in Hongjian originally constructed by a returned Filipino Chinese in the Ming dynasty and rebuilt by another Filipino Chinese after the original was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (The same village of Hongjian, in Fujian’s Jiaomei township, is also the ancestral home of former Philippine President Corazon Aquino).

In Cambodia, some legends have Zheng He magically traveling with his fleet to Phnom Kulen, where a dented peak would be in fact his ‘wrecked ship’ (សំពៅធ្លាយ [sâm-pov thleay]). Sinologist and Khmerologist Pascal Médeville has identified a Chinese temple dedicated to Zheng He at Nokor Banchey (ប្រាសាទនគរបាជ័យ), near Kampong Cham. There, he is referred to as Sanbao » (三保公庙), and a local legend has him being a Khmer prince from Kampong Cham who went to China:

(Photo by Pascal Médeville)

More about Zheng He:

Zheng He flagship scale compared to Columbus ship at Dubai Exhibition, 2006

- The admiral-eunuch as a propagator of the Muslim faith across Southeast Asia (article by Afifa Thabet)

- While most historians argue that Zheng He died in Nanjing, China, of which is was the military commandeer, some state that he actually passed away in India. More about the Chinese fleet in Calicut here and here.

A tribute to Zheng He travels during the 2018 Olympic Games opening ceremony in Beijing.

- As the Xi Ping régime is prone to exalt Zheng He’s heritage of ‘peaceful diplomacy’, were his expeditions a form of ‘proto-colonialism’? Read about the controversy.

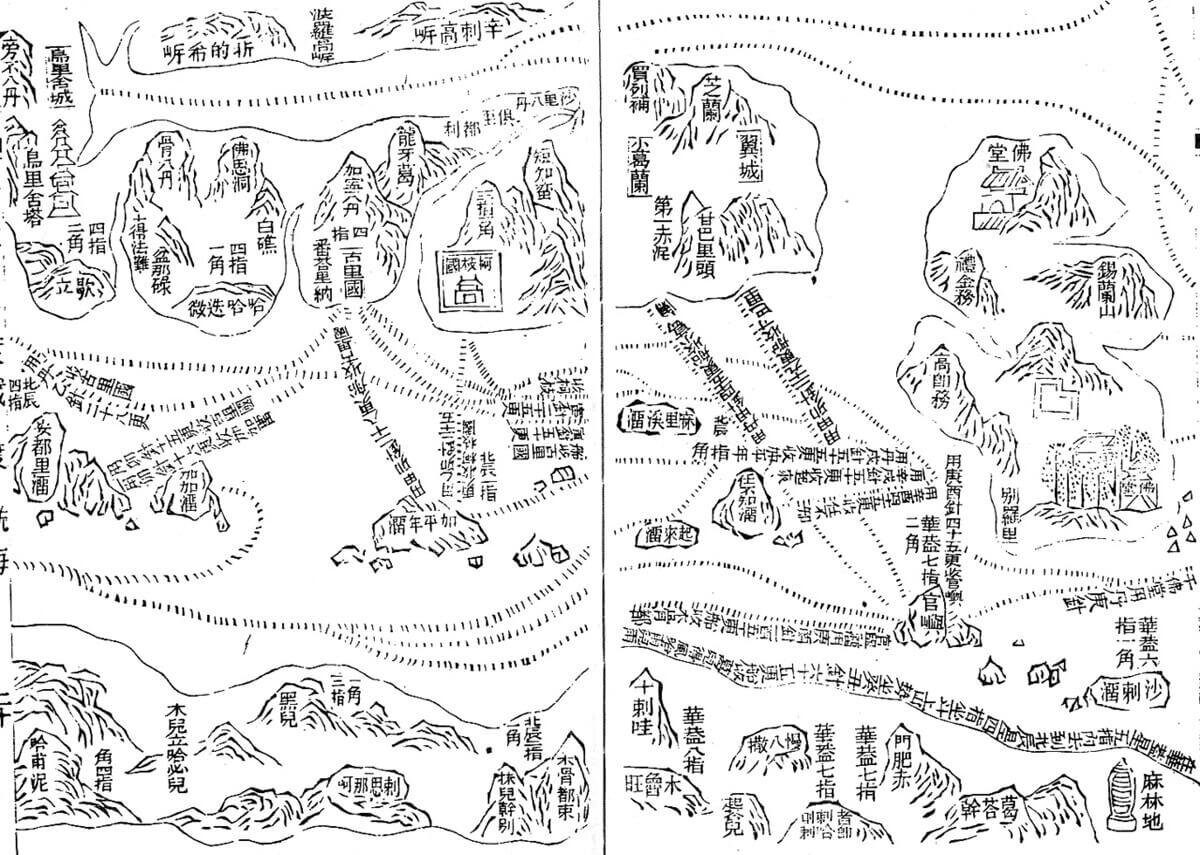

The famous Mao Kun Map retracing Zheng He voyages (Wikipedia Commons)

- More about the technological resources of a fleet of some 30,000 men and 317 ships: Mark Dwinnels, ‘Lost Leviathans: The Technology of Zheng He’s Voyages’, Bridgewater University Undergraduate Review 4 – 23, 2008.

Tags: China, Chinese travelers, Chinese explorers, maritime routes, Islam, Queen Mother Monineath, Zheng He, translations, marriage, Chams, Champa, Chenla, Arabic Peninsula

About the Author

Ma Huan

Ma Huan 馬歡 ﻣَﺎ ﺧُﻮًا (c. 1380, Kuaiji, Zhejiang Province, China –1460) [courtesy name Zongdao 宗道, pen name Mountain-woodcutter 會稽山樵] was a Chinese voyager and translator who accompanied Admiral Zheng He on three of his seven expeditions to the Western Oceans.

Like Zeng He (romanized Cheng Ho) — who was born as Ma He (馬和) to a Muslim family of Kunyang, Kunming, Yunnan –, Ma (Chinese diminutive of ‘Muhammad’) Huan was a Muslim born in the Kuaiji Commandery, an area within the modern borders of Shaoxing. He knew several Classical Chinese and Buddhist texts, and learned Arabic to be able to translate during his travels.

In the 1413 expedition (the 4th), he visited Champa, Java, Sumatra, Palembang, Siam, Kochi and Hormuz. In the 1421 expedition, he visited Malacca, Aru, Sumatra, Trincomalee, Ceylon, Kochi, Calicut, Zufar and Hormuz. In the 1431 expedition, he visited Bengal, Chittagong, Sonargaon, Gaur and Calicut.

It his assumed that he was among the emissaries sent to Mecca in 1432 – 1433 by Eununch Hong Bao — or by Zeng He himself, who also an eunuch at the court of Ch’eng-tsu (Yung-lo, the Yongle Emperor) — from Calicut, Kerala, India (now Khozikode). Funded in the 11th century, Calicut was then known as “the City of Spices”, and had been visited by the Arab voyager Ibn Battuta in the 1340s. Explorer Vasco de Gama was to visit the city in 1498.

Back to China, Ma Huan worked on his travel account with a travel companion, Kuo Chung-li, and the first edition (lost) of the Ying-yai Sheng-lan was published in 1451.

Main photo: A 17th engraving representing one of the “treasure ships” of Zeng He’s flotilla. The massive ships were often near 152 meter long, and 500 to 1,000 passengers could be onboard. Above: A reconstitution of the flotilla in Beijing (Reuters)

About the Translator

John Vivian Gottlieb Mills

J.V.G. Mills (1887, Hastings, UK ‑1987, Geneva, Switzerland) was a British colonial administrator and judge appointed to the Straits Settlements at age 24, a translator from Cantonese, Fukienese and standard Chinese, and a specialist in Southeast Asia seamanship and seaways.

Based in Canton for two years, he mastered the language before going back to Singapore where he was Solicitor-General, Attorney-General and judge for the Straits Settlements. Retired in 1940 (aged 53), he went to Australia and returned to England after the war to take his MA at Oxford in 1945 and lecture at the School for a year in Chinese law. Settling in Switzerland on the shores of Lac Leman, he was helped by his second wife, Marguerite Mélanie Mills née Service (1887−1983) — to whom he dedicated his magnus opus –, a specialist in Chinese art, in pursuing his research and perusing his notes taken at the Raffles Library.

It was while researching Emanuel Godinho de Eredia’s 1613 book that he came across the XVI th century sea chart of Mao K’un and the Wu-pei chih by Mao’s grandson Yuan‑i (Eredia’s contemporary). From late Ming, Mills was drawn back to sources in early Ming, and thence to the voyages of eunuch Cheng Ho (the Sam-poh Kung patron of Overseas Chinese legend) round Southeast Asia and across the Indian Ocean commissioned by the emperor Yung Lo, in the age of Henry the Navigator. He was now equipped to undertake translation and commentary on the Ying-yai Sheng-lan, in which, in 1433, Ma Huan told the story of Cheng Ho’s seven voyages, using the modern text established by Feng Ch’eng-chun (1935 and 1955) and drawing on the collaboration of half a hundred other scholars to light up dark corners.

While French sinologist Paul Pelliot had earlier translated parts of that work, it was the first complete translation into an European language, eventually published in 1970 by the Hakluyt Society (of which Mills had been an Honorary Secretary) as Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores. In 1996, Roderich Ptak offered a revised and annotated edition: Hsing-ch’a sheng-lan : The Overall Survey of the Star Raft by Fei Hsin, translated by J.V.G. Mills, South China and Maritime Asia 4, 1996, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 154 p. [ISBN 3 – 447-03798 – 9].